Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are idiosyncratic blistering diseases of the skin, most commonly triggered by medications, with overlapping clinical presentations. Mucous membranes are affected in over 90% of patients, usually at two or more distinct sites (occular, oral, and genital).1

Controversy has existed in the literature in relation to the clinical definitions of these diseases and whether they are distinct entities or a spectrum of one disease process. There is now consensus that SJS and TEN are variations of the same condition, but are different from erythema multiforme, 2 a similar condition which is covered separately. (Erythema multiforme Major and Minor).

Classification depends on severity and percentage of body surface affected by blisters and erosions. TEN is more severe than SJS with identical pathology.3

Epidemiology

SJS incidence is 1.2–6 per million person-years. Incidence of TEN is 0.4–1.2 per million person-years. Both diseases can occur at any age but are most common in adults over 40 years. It is slightly more common in women than in men (1.5:1).4 The overall mortality rate among patients with SJS/TEN is approximately 30 percent, ranging from approximately 10 percent for SJS to up to 50 percent for TEN. Mortality continues to increase up to one year after disease onset.5

Etiology

The pathogenesis of this condition is not completely understood.

With medications the leading trigger, the risk of SJS/TEN seems to be limited to the first eight weeks of treatment. Drugs used for a longer time are unlikely to be the cause of SJS/TEN. The typical exposure period before reaction onset is four days to four weeks of first continuous use of the drug. However, approximately 25 to 33 percent of cases, and probably an even higher proportion of pediatric cases, cannot be clearly attributed to a drug.6

Stevens Johnson syndrome (SJS)

In the literature, 50% of SJS cases are associated with drug exposure, but this is likely an underestimate due to previous confusion regarding the distinction between SJS and Erythema Multiforme.7 8

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

80% of TEN cases have strong association with specific medication. Less than 5% report no drug use.9 External chemical exposure, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, viral infections, and immunizations are also implicated.

Medications and Risk of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

| HIGH RISK | LOWER RISK | DOUBTFUL RISK | NO EVIDENCE OF RISK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allopurinol | Acetic acid NSAIDs | Paracetamol (acetaminophen) | Aspirin |

| Sulfamethoxazole | Aminopenicillins | Pyrazolone analgesics | Sulfonylurea |

| Sulfadiazine | Cephalosporins | Corticosteroids | Thiazide diuretics |

| Sulfapyridine | Non-acetic acid | NSAIDs except aspirin | Furosemide |

| Sulfadoxine | Cyclins | Sertraline | Aldactone |

| Sulfasalazine | Macrolides | Calcium channel blockers | |

| Carbamazepine | Beta blockers | ||

| Lamotrigine | ACE inhibitors | ||

| Phenobarbital | Angiotensin II receptor antagonists | ||

| Phenytoin | Statins | ||

| Phenylbutazone | Hormones | ||

| Nevirapine | Vitamins | ||

| Oxicam NSAIDs | |||

| Thiacetazone |

Source: Vakeyrue-Allanore L, Roujeau J-C: Epidermal necrolysis, in Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7e, K Wolff, et al (eds). New York, McGraw-Hill, 2008, Chap. 39.

Symptoms and clinical features

The difference between SJS and TEN relates to how much of the body surface is affected.

- SJS: <10% epidermal detachment

- SJS/TEN overlap: 10-30% epidermal detachment

- TEN: >30% epidermal detachment10 11

In both SJS and TEN, fever, malaise, and arthralgias may present one to three days prior to mucocutaneous lesions. Mild to moderate skin tenderness, conjunctival burning or itching, then skin pain, burning sensations, tenderness, and paresthesias may develop. Mucosal lesions of the mouth and vulva are painful, and tender to touch. Depending on areas of involvement, there may be impaired alimentation, photophobia, painful micturition, and anxiety.12

There is then a sudden onset of erythematous, flat papules that develop darker, dusky erythema centrally. This color results from more severe inflammation in that location and produces the classic target lesions of these diseases.

(PICTURE from Kelly Tyler)

About 50% of TEN cases do not develop these papules, but rather, go from diffuse erythema to necrosis and epidermal detachment. The inflammation and epidermal necrosis lead to separation of the epidermis from the dermis, forming either blistered or sloughing tissue. Blisters on keratinized epithelium, along with erosion of mucous membranes, characterize SJS and TEN. They then manifest with coalescing of erythematous tissue and sheets of denuded epithelium.13

Epidermal sloughing may take place within hours or days.

If widespread lesions exist, patients are toxic, risk secondary infection, and are similar in needs to burn patients.

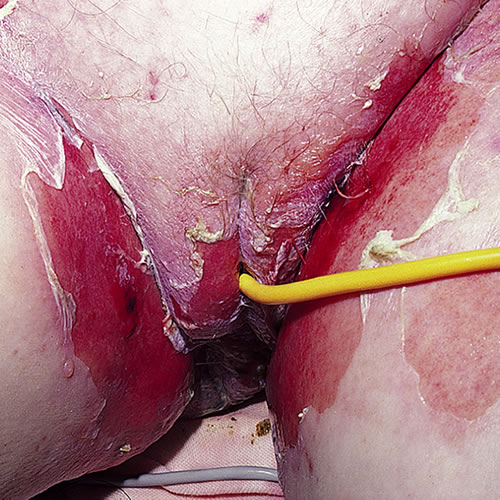

Vulvovaginal involvement is common. In one series, 70% of patients hospitalized for TEN developed genital lesions, including erosive and ulcerative vaginitis, vulvar bullae and vaginal synechiae. Long-term sequelae such as labial agglutination and introital stenosis occurred in 18% of these women,14 and up to 28% of women in another series.15 Entry dyspareunia and postcoital bleeding are the most common complaints arising from scarring; urinary retention, recurrent cystitis, post-void dribbling, hematocolpos, and endometriosis may also result from post-inflammatory obstruction of the urinary stream and menstrual flow.16 Vulvovaginal adenosis as the endpoint to a chemical insult is commonly reported in women who have had SJS and TEN, and may result in stricture formation.17 18 The malignant potential of vulvovaginal adenosis in non-DES exposed women is unknown,19 but transformation to adenosis with cellular atypia, squamous cell carcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and clear cell carcinoma of the vagina have been reported. 20 21 22

Risk factors for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) include HIV infection, genetic factors, underlying immunologic diseases or malignancies, and, possibly, physical factors (such as ultraviolet light or radiation therapy).23

Diagnosis

A patient with vulvovaginal symptoms will have the history of target-like skin lesions, possibly ocular or oral lesions, and ingestion of a medication known to produce this reaction. (See Table of Medications, above).

Diagnosis should be confirmed by biopsy to rule out other diseases such a pemphigus vulgaris or mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid) that would be treated entirely differently.24 Cultures of skin, oral mucosa, sputum, and blood to rule out bacterial disease, and culture plus serology for herpes are important.

Pathology/laboratory findings

Histopathology is similar for both SJS and TEN, but varies in degree depending on the severity of the condition. 25

A predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate occurs, mainly at the dermal-epidermal junction and superficial perivascular region. T cells in the dermis are predominantly CD4+, while CD8+ cells are seen in the epidermis. Vacuolization/necrosis of basal keratinocytes and apoptosis eventually throughout the full thickness of the epidermis may also develop. Subepidermal bullae are characteristic.26 Blistering is preceded by the presence of increased levels of soluble Fas ligand levels in serum. Fas mediates keratinocyte apoptosis.

Differential diagnosis

Early cases may masquerade as drug eruption, scarlet fever, phototoxic eruptions, toxic shock syndrome, or graft-versus-host disease.

Fully evolved disease mimics thermal burns, phototoxic reactions, staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome, bullous fixed drug eruption, pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid), primary herpes.

Psoriasis, secondary syphilis, urticaria, and generalized Sweet syndrome deserve consideration.27

Treatment/management

Treatment includes stopping intake of the suspected causative medication. Antivirals are useful for recurrent HSV only when they are begun immediately.

Supportive care includes aggressive identification and treatment of secondary bacterial or Candidal infection and fluid loss. Dermatological and ophthalmological consults will be important.

Local vulvovaginal care will include sitz baths in comfortable water 3-4 times daily followed by application of plain petrolatum.

There are no controlled trials of therapy for SJS or TEN. Use of systemic steroids is controversial with strong advocacy by some,28 29 while others consider corticosteroids to be contraindicated.30 Early institution of corticosteroids can limit blistering, but sustained use or use after blistering has developed does not improve the condition and compromises the prognosis by increasing the risk of adverse reaction to the steroid.31

Class I steroid topicals such as augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% or clobetasol 0.05% have been used on the vulva and intravaginally in patients with ulcerative lesions of SJS and TEN.32 Although almost half the mortality from TEN is related to infection, it is unlikely that systemic absorption of topical steroids increases the risk of sepsis in these patients.33 If the vulva is involved, start topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment in a thin film, nightly.

If the vagina is involved, it is important to be aggressive in treatment to prevent mucosal scarring. Start the patient on hydrocortisone 10% in petrolatum 1 g per vagina nightly after use of a vaginal dilator (small Syracuse® or other Milex® dilator if there has been no sexual activity recently, medium for sexually active women) for 20 minutes.

Steroids are continued until the acute inflammation resolves (~ two weeks). The dilator should be used daily for two months or longer if necessary. Dilator use in a virginal patient requires special consideration and individualization. If a young woman is comfortable with tampon use, a small dilator may be well tolerated. The alternative is use of the intravaginal steroid with an applicator every other day. One author recommends that no dilator treatment be initiated in the pediatric patient until she is an adolescent and able to manage the dilation process without emotional trauma.34 Prophylaxis against Candida is suggested with fluconazole orally, 150 mg weekly or clotrimazole 1% one g vaginally twice weekly.

The calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus 0.1% used intravaginally has been successful in preventing vaginal stenosis in erosive lichen planus,35 but has not been studied in relation to SJS and TEN. A burning sensation upon initial application in some patients would likely limit its use on eroded skin or mucous membranes.

Several reports of TEN and SJS note the subsequent development of vulvar or vaginal adenosis.36 37 38 Menstrual suppression during the healing process to decrease the risk of vaginal adenosis is considered a reasonable approach.39 No cases of adenosis have been described in patients between one month and twelve years of age. If adenosis is present on biopsy, down regulation with a three month course of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) has been reported to improve pain significantly.40 Add-back of norethindrone acetate 5 mg by mouth once daily will mollify menopausal symptoms and protect bone mineral density. An alternative would be oral contraceptive pills for menstrual suppression. Because of the association of adenosis with cancer (LINK to Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium), monitoring by colposcopy is suggested.

As with corticosteroids, some authors report good results with the use of human intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs).41 IVIG contains antibodies that inhibit Fas-mediated keratinocyte apoptosis, but the utility of the treatment remains controversial.42

Infliximab has been used successfully to stop disease progression and achieve healing, but numbers are small and no trial was controlled.43 44 Cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis have also been used.45

References

- High, WA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate, 2022. www.uptodate.com

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York, McGraw Hill Medical, 2009. 173.

- Wilkins J, Morrison L, White CR. Oculocutaneous manifestations of the erythema multiforme/Stevens Johnson /toxic epidermal necrolysis spectrum. Dermatol Clin.1992; 10:571-582.

- French, L and Prins, C. Erythema Multiforme, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome & Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Dermatology, edited by Jean Bolognia, Elsevier Limited, 2018.

- High, WA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate, 2022. www.uptodate.com

- High, WA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate, 2022. www.uptodate.com

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York, McGraw Hill Medical, 2009. 173.

- French, L and Prins, C. Erythema Multiforme, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome & Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Dermatology, edited by Jean Bolognia, Elsevier Limited, 2018.

- Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medications risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs. The EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008. 128(1):35-44.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York, McGraw Hill Medical, 2009. 174.

- High, WA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate, 2022. www.uptodate.com

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York, McGraw Hill Medical, 2009. 173.

- Edwards, L. Erosive and vesiculobullous diseases. In: Edwards L, Lynch PJ, eds. Genital Dermatology Atlas, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. 144.

- Meneux E, WolkensteinP, Haddad B, et al. vulvovaginal involvement in toxic epidermal necrolysis: a retrospective study of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 91:283-287.

- Niemeijer IC, van Praag MC, van Gemund N. Relevance and consequences of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in gynecology. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009; 280:851-854.

- Wilson EE, Malinak LR. Vulvovaginal sequelae of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and their management. Obstet Gynecol.1988; 71:478-480.

- Emberger M. Lanschuetzer CM, Laimer M, et al. Vaginal adenosis induced by Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006; 20:896-898.

- Noel JC, Buxant Fm Fayt I, et al. Vulval adenosis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2005; 153:457-458.

- Kaser DJ, Reichman DE, Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 4(2):81-85.

- Kranl C, Zelger B, Kofler H, et al. Vulval and vaginal adenosis. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 139:128-131.

- Scurry J, Planner R, Grant P. Unusual variants of vaginal adenosis: a challenge for diagnosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 1991; 41:172-177.

- Yaghsezian J, Palazzo JP, Finkel GC, et al. Primary vaginal adenocarcinoma of the intestinal type associated with adenosis. Gynecol Oncol. 1992; 45:62-65.

- High, WA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate, 2022. www.uptodate.com

- Edwards, L. Erosive and vesiculobullous diseases. In: Edwards L, Lynch PJ, eds. Genital Dermatology Atlas, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. 146.

- Lissia M, Mulas P, Bulla A, Rubino C. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s disease). Burns. 2010; 36:152-163.

- Worswick S, Cotliar J. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2011; 24(2):207-218.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York, McGraw Hill Medical, 2009, 173.

- Hynes A, Kafkala C, Daoud Y, et al. Controversy in the use of high dose systemic steroids in the acute care of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Int J Ophthamol Clin. 2005; 45(4):25-48.

- Yamane Y, Aihara M, Tatewaki S, et al. analysis of treatments and deceased cases of severe adverse drug reactions-analysis of 46 cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Jpn J Allergo. 2009; 58:537-547.

- Lissia M, Mulas P, Bulla A, Rubino C. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s disease). Burns. 2010 Mar;36(2):152-163.

- Edwards, L. Erosive and vesiculobullous diseases. In: Edwards L, Lynch PJ, eds. Genital Dermatology Atlas, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. 149.

- Amankwah YA, Haefner HK, Brincat CA. Management of vulvovaginal strictures/shortened vagina. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 53:125-133.

- Niemeijer IC, van Praag MC, van Gemund N. Relevance and consequences of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in gynecology. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009; 280:851-854.

- Kaser DJ, Reichman DE, Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2011; 4(2):81-85.

- Amankwah YA, Haefner HK, Brincat CA. Management of vulvovaginal strictures/shortened vagina. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 53:125-133.

- Emberger M, Lanschuetzer CM, Laimer M, et al. Vaginal adenosis induced by Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:896–898.

- Noël JC, Buxant F, Fayt I, et al. Vulval adenosis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:457–458.

- Bonafe JL, Thibaut I, Hoff J. Introital adenosis associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:356–357.

- Kaser DJ, Reichman DE, Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 4(2):81-85.

- Emberger M. Lanschuetzer CM, Laimer M, et al. Vaginal adenosis induced by Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006; 20:896-898.

- Prins C, Kerdel F, Padilla R, et al. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins: multicenter retrospective analysis of 48 consecutive cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003; 139(1):26-32.

- Lissia M, Mulas P, Bulla A, Rubino C. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s disease). Burns. 2010 Mar;36(2):152.

- Meiss F, Heimbold P. Meykadeh N, et al. Overlap of acute generalized exanthemoatous pustulosis and toxic epidermal necrolysis: response to anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha antibody infliximab: report of three cases. J Eur Acac Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21:717-719.

- Wojtkiewicz A, Wysocki M, Fortuna J, et al. Beneficial and rapid effect of infliximab on the course of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008; 88:420-421.

- Worswick S, Cotliar J. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of treatment options. Dermatol Ther . 2011; 24(2):207-218.