Annotation F: The vulvar architecture

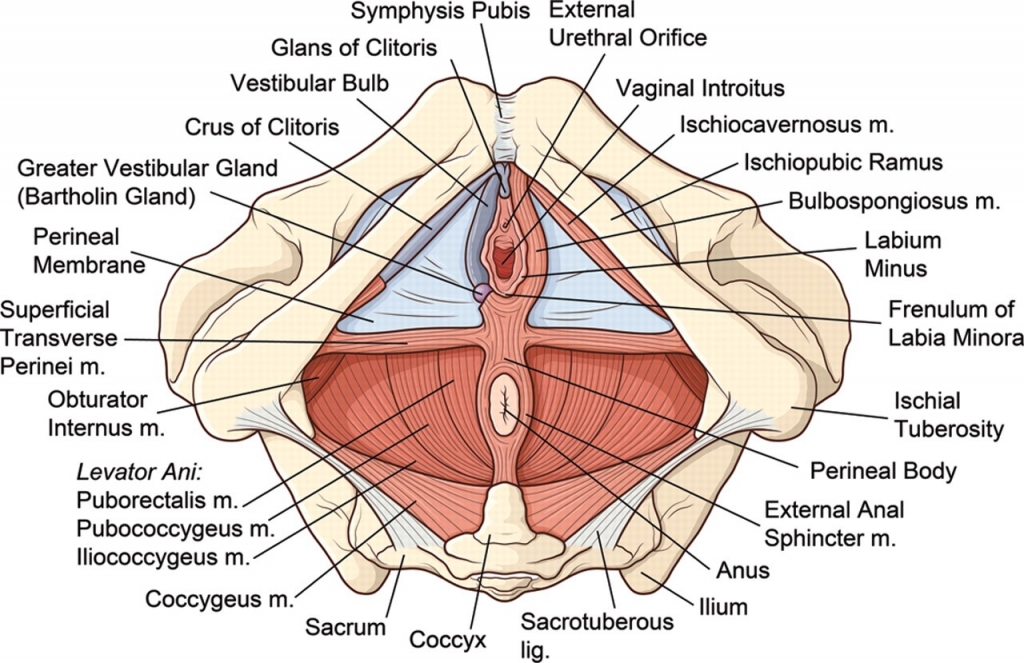

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationThe vulva is located within a diamond-shaped area between the legs called the perineum. The perineum includes the anterior boundary of the pubic symphysis, and the posterior boundary of the tip of the coccyx. The lateral margins are the ischiopubic rami. (This perineum is different from the area also called perineum between the vagina and rectum; any reference to perineum in the algorithm or the rest of the website refers to the tissue between vagina and rectum). The perineal diamond is further divided into an anterior urogenital triangle and posterior anal triangle. The vulva lies mainly within the anterior urogenital triangle but extends anteriorly to the symphysis pubis. The anal canal and the ischiorectal fossa occupy the posterior anal triangle.

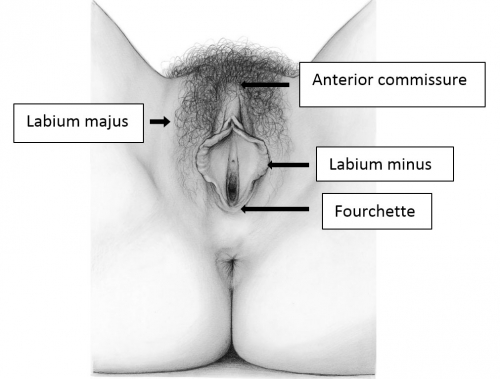

The vulva consists of the mons pubis, the labia majora and minora, the vestibule of the vagina, including the external urethral orifice, the greater vestibular glands of Bartholin and the lesser vestibular glands, and the clitoris with its prepuce and frenulum. The hymen, or its remnants, form the entry to the inner structure of the vagina.

Accurate and detailed descriptions of the external female genitalia have been debated for years. Even most medical textbooks lack information on vulvar morphology. 1 A description of the normal appearance of the labia minora, evolved over time.2 What clinicians today believe is a ‘normal vulva’, is based on limited data from the beginning of the 20th century.3

Efforts to create valid standards have started to appear in recent years. A cohort study of pre- and postmenopausal women showed that a wide variation in the appearance of female genitalia exists, and concluded that further studies including clear definitions are needed on the ‘normal’ appearance of the vulva.4

The lack of standards and definitions of the “normal” vulva is impacting reproductive-age women who are questioning the appearance of their own external genitalia. Despite the fact that appearance differs depending on ethnicity, age, weight, hormonal status, and type of skin, young women are seeking a “perfect” body image, a body image influenced by the media (including social media) and peer pressure, resulting in rising numbers of cosmetic surgery consultations.

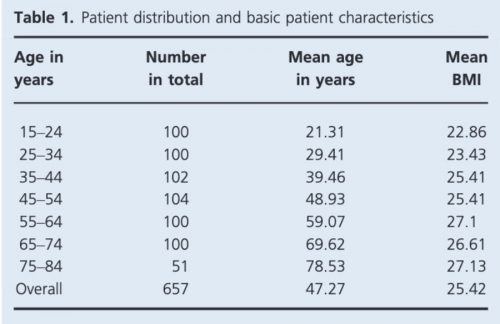

A prospective cohort study of white women aged 15-84 years published in 2018 aimed to set up a database to represent reliable standard values concerning the external female genitalia and its appearance.5

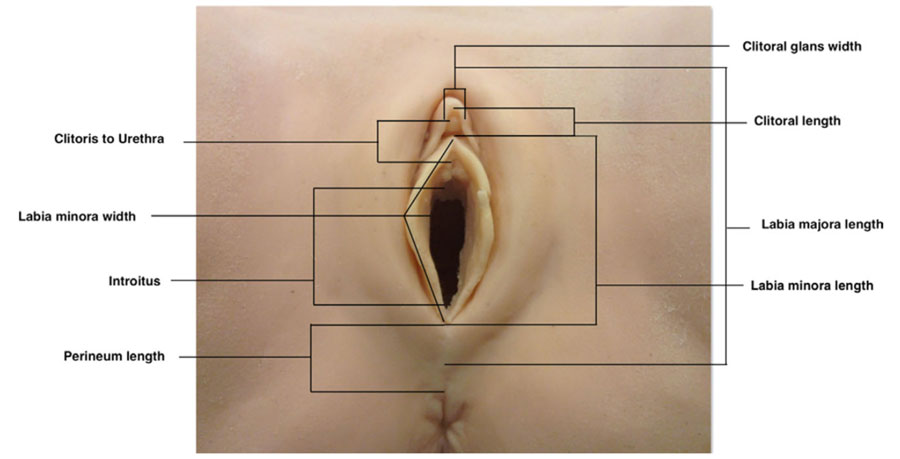

Measurements of the external female genitalia were performed in lithotomy position using a disposable paper measure. Analysis was performed for each site: width of the clitoral gland, clitoral length, distance from the base of the gland to the urethral orifice, length of introitus, length of perineum (posterior fourchette to anterior anal margin), length of labia major, length of labia minor (from the clitoris to the lower margin of the labia), width of labia minora (from the sulcus infralabialis to the margin of the labium minora, not stretched). Values are visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Standard measurements of the external female genitalia.6

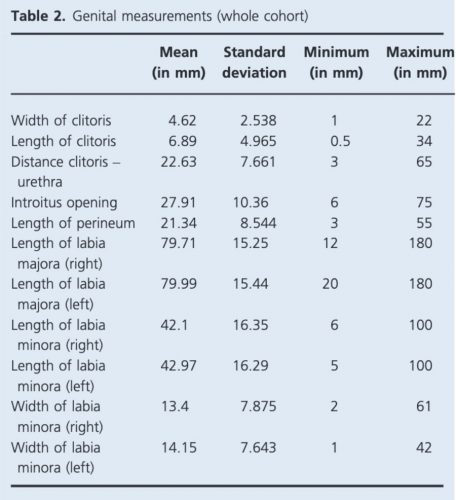

Basic characteristics of the women in the study are summarized in Table 1. Average measurements of the vulva incorporating the whole cohort are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 1. Patient distribution and basic characteristics.7

Table 2. Genital measurements (whole cohort).8

The study represents a baseline for the appearance of a normal white vulva, and sets up standards for indications for gynecological cosmetic surgery The authors chose to include white women only, to create a homogenous group of just one ethnicity. Hopefully this study will pave the way for further studies publishing data on different ethnicities and heterogeneous groups of women around the world.

The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) and the International Continence Society (ICS), as the leading societies in their fields, support the warning issued by the FDA on July 30 2018, concerning the use of energy based devices (radio frequency and LASER) for vaginal “rejuvenation” (a not-scientifically defined term), vaginal cosmetic procedures or procedures intended to treat vaginal conditions and symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence, or sexual function.9

It is important to remember that adequate evaluation of the vulva (Latin, covering) requires both inspection of the external structures and separation of the labia majora and minora to evaluate the underlying structures.

PHOTOS OF NORMAL VULVAS

Figure F-3: Examples of normal vulvae. All have normal variations in labia minora, color, and texture.

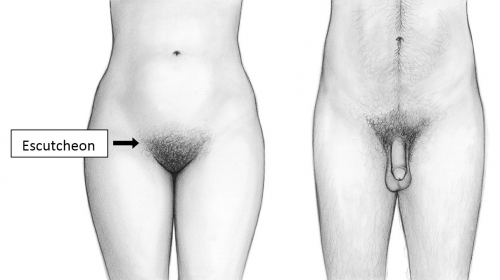

The mons pubis

The mons pubis or mons veneris (Latin, mountain of Venus) becomes an identifiable structure with puberty when a subcutaneous fat pad is deposited over the symphysis pubis and pubic hair appears.

The combination of fat and hair over the bony pubis acts as a cushion to prevent discomfort with intercourse; it would appear that the fat pad alone is sufficient in most cases for those who prefer pubic hair removal. The fat pad remains even after marked weight loss.10 The covering pubic hair, hormonally regulated, is the escutcheon. The female escutcheon forms an inverted triangle; the male escutcheon grows upward onto the abdomen. The male pattern can be seen in normal women, depending on race and heredity. Hair characteristics vary according to ethnicity.

Vascular supply: The vascular supply comes from the external pudendal artery, branch of the femoral and pudendal veins to the long saphenous vein.

Nerve supply: Nerve supply is the deep branch of the perineal nerve arising from the pudendal nerve.

The labia majora

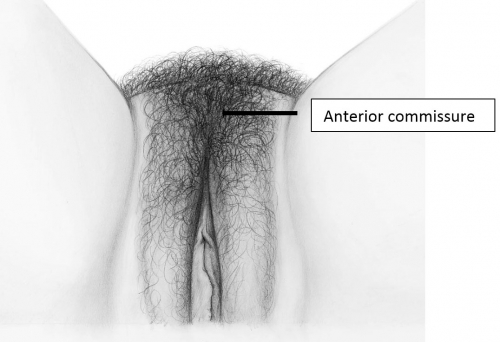

The labia majora (and mons) form the lateral and cephalad boundaries of the external genitalia. Two elongated, rounded folds of squamous epithelial skin, covered laterally with pubic hair fuse in the midline of the mons as the anterior commissure.

The labia majora act as a cover for the structures deep to them. Involuntary muscles are much less developed than the labial counterpart, the scrotum. After puberty, lobules of fat separated by elastic and connective tissue fibers give the labia further definition. The round ligaments of the uterus enter the superior labia majora and disperse their fibers into a well-defined sac of elastic connective tissue. This sac is medial to the inguinal canal.

Vascular supply: The vascular supply comes from the pudendal artery via the posterior labial branch and from a small branch of the obturator artery. Venous drainage goes to the posterior labial, pudendal and obturator veins but also communicates with the vesicovaginal plexus and inferior hemorrhoidal veins.

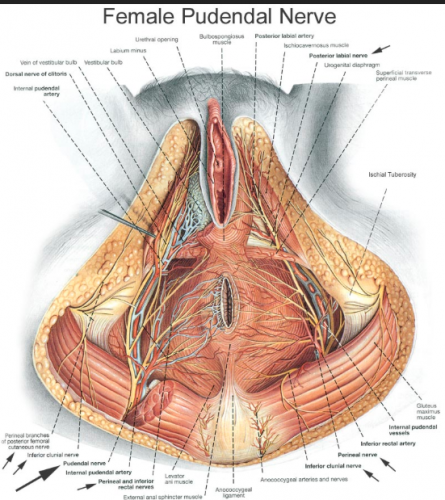

Nerve supply: The nerve supply is complex. It derives from the pudendal nerve (S2, 3, and 4); the pudendal forms a perineal branch from which the posterior labial nerve arises to supply the majora and the lateral portion of the urethral triangle.11

Additional innervation comes from the ilioinguinal, internal branch of the genitofemoral, and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerves.

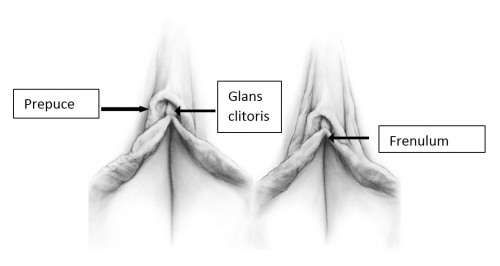

The labia minora, interlabial sulci, prepuce and frenulum

The labia minora are two thin folds of hairless skin, lacking subcutaneous fat, located between the labia majora on either side of the vaginal and urethral openings. They have convex free borders. The minora are separated from the majora by shallow, interlabial grooves, the interlabial sulci. The minora may be hidden by the majora or may project between the majora. Anteriorly, in the clitoral area, the minora divide into lateral and medial parts.12

The lateral parts of the labia minora unite anterior to the clitoris in a hood of skin overhanging the glans clitoris, the prepuce (Latin, foreskin).13 The prepuce covers all or part of the most highly sensitive tissue in the body, the clitoris. Cephalad displacement of the right and left labia minor enables full retraction of the clitoral prepuce and complete exposure of the glans clitoris under normal circumstances.14 The prepuce is endowed with numerous sebaceous glands and mucous secreting glands to prevent friction.

The medial parts of the minora unite on the undersurface of the clitoris to form its supporting frenulum (Latin, a small bridle). The minora may further divide, unilaterally or bilaterally, to form additional fold(s) lateral to the prepuce.

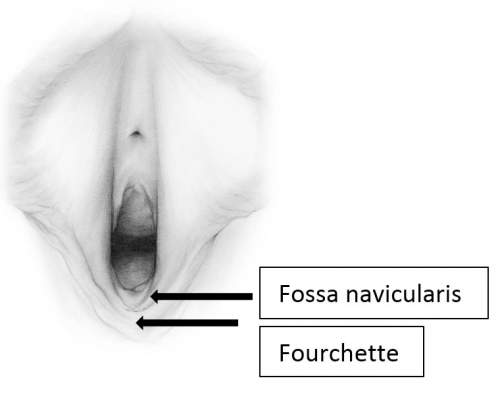

The labia minora fuse posteriorly to form a transverse fold inferior to the vaginal opening, the fourchette (little fork). 15

Between the fourchette and the hymenal ring is a curved depression shaped somewhat like a tiny boat, the fossa navicularis. (drawing by Dawn Danby from The V Book by Elizabeth G. Stewart, MD)

The labia minora engorge as part of sexual arousal; they also prevent spraying of the urinary stream.

Vascular supply: The vascular supply comes from the posterior labial branch of the pudendal and from the terminal branch of the internal pudendal artery, the dorsal artery of the clitoris.

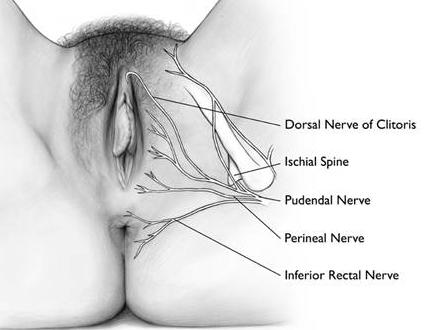

Nerve supply: The nerve supply is the same innervation as that of the majora, the perineal branch from which the posterior labial nerve arises to supply the majora and the lateral portion of the urethral triangle.16 Additional innervation comes from the ilioinguinal, internal branch of the genitofemoral, and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerves. (See picture above.)

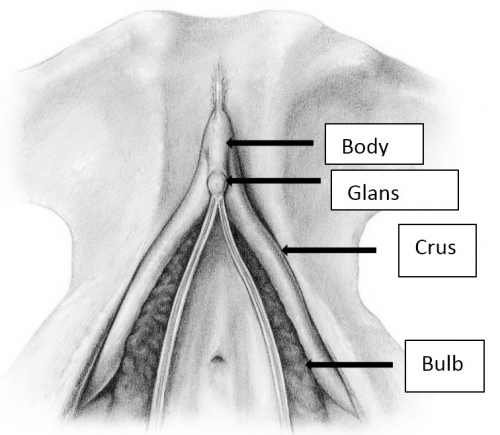

The clitoris

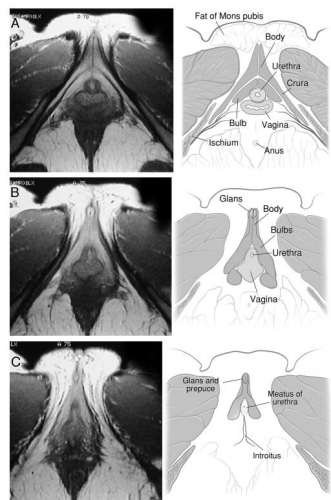

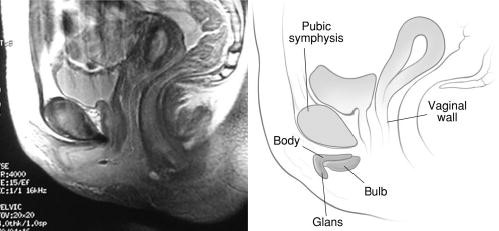

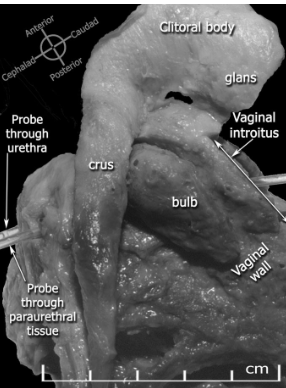

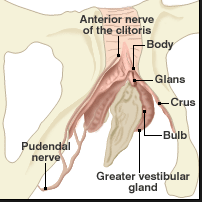

The clitoris is impossible to convey in a single monoplanar diagram as a flat structure. Work with magnetic resonance imaging, combined with anatomic dissection, shows that the clitoris is a multiplanar structure in a wishbone shape. It has erectile tissue parts- the body or corpora (often called shaft), two crura and two clitoral bulbs.17 The glans is a densely neural structure that is, contrary to popular belief, not erectile in nature, but is in direct continuity with the erectile bodies to which it attaches.18 The two arms of the wishbone are the paired crura, which extend forward as the corpora cavernosa, meeting in the midline to form the clitoral body or shaft. The crura are attached to the pubic rami and are covered by the ischiocavernosus muscle. The clitoral body is attached to the symphysis pubis by a suspensory ligament. The tip of the clitoral body bends anteriorly away from the pubis in a boomerang appearance to form the glans. The glans is covered partially or completely by the prepuce or hood formed by the labia minora. As with the labia minora, variants of the prepuce are described but not documented. In the absence of disease, the examiner should be able to retract the clitoral hood gently, easily, and painlessly, superiorly to expose the entire glans clitoris.19 Total or partial adherence of the prepuce to the glans suggests scarring vulvitis and observation and/or treatment is needed.

The clitoral bulbs are located between each crus and the vaginal orifice. Formerly called the vestibular bulbs, the clitoral bulbs are renamed since anatomically they form part of the clitoris.2021

Helen E. O’Connell and John O.L. DeLancey. J Urol. 2005 Jun; 173(6): 2060–2063. Used with permission.

Helen E. O’Connell and John O.L. DeLancey. J Urol. 2005 Jun; 173(6): 2060–2063. Used with permission.

O’Connell HE, Kalavampara VS, Hutson JM. Anatomy of the clitoris. JUro. 2005; 174(4);1189. Used with permission.

The urethral orifice (external meatus) is located between the body of the clitoris and the vaginal opening in the midline, about an inch postero-inferior to the glans clitoris. A sexually sensitive area in the anterior vaginal wall is termed the Grafenberg or G-spot. Ultrasound studies have demonstrated that the site of greatest sensitivity corresponds to the location of the external urethral sphincter. There is no consensus, however, regarding the presence of the G-spot.22 It is likely that the increased area of sensitivity reported in some women in relation of the urethra is because the urethra is surrounded by erectile tissue of the two clitoral bulbs.23

All the components of the clitoris but the glans lie beneath the skin. The glans clitoris is visible under its prepuce or with gentle retraction of the prepuce. Although there is significant variability in clitoral size in normal women, in one study, mean glans clitoral length and width were 5.1 ± 1.4 mm and 3.4 ± 1.0 mm, respectively. However, clitoral enlargement is typically determined on the basis of clitoral length or the clitoral index (length times width): length >10 mm or an index >35 mm2 is considered above normal.242526

Women who have had children tend to have larger clitoral measurements but still within the norm.27

The clitoris, unlike its counterpart, the male penis, has the single function of sexual enjoyment and plays no role in reproductive or urinary function.

Vascular supply: The vascular supply comes from the superficial and deep branches of the internal pudendal artery; venous drainage goes to the deep dorsal vein to vesicle plexus, deep external pudendal veins to femoral vein, and internal pudendal veins to internal iliac vein

Nerve supply: The nerve supply arises from the dorsal nerve of the clitoris, a branch of the pudendal nerve. The dorsal clitoral neurovascular bundles arise along the crus on each side of the pelvic sidewall, plastered to the periosteum of the pubic ramus; these bundles supply the crus, body, and glans of the clitoris and the superficial tissues of the labia. The bulbs and urethra are supplied by the perineal neurovascular bundle. The dorsal nerve of the clitoris runs anterosuperomedially from its formation underneath the ischiopubic ramus and runs along the superior surface of the corpus clitoris, not in the 12 o’clock position, to enter the deep aspect of the glans clitoris. The perineal neurovascular bundle runs medially and more horizontally after its formation, to reach the posterolateral aspect of the bulbs.28

The vestibule of the vagina

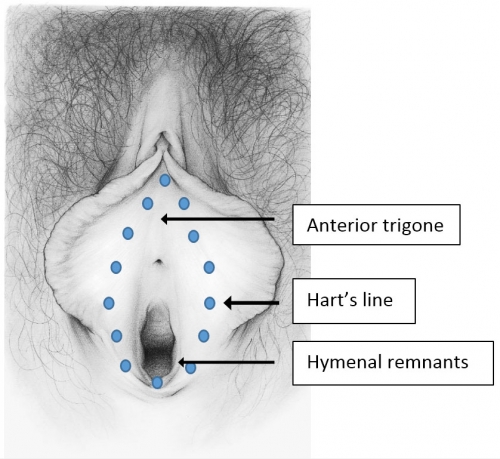

This narrow elliptical space just inside the labia minora extends from the frenulum to the fourchette; the lateral boundaries are Hart’s line, delineating the change from keratinized epithelium laterally to non-keratinized epithelium medially. The medial boundary is the hymenal ring.

The name (vestibule) comes from the number of doorways entering the space: urethra, vagina, eccrine gland ducts, ducts of the minor vestibular glands and the major vestibular glands of Bartholin. This tissue, derived from endoderm that customarily lines the organs such as the respiratory and gastro-intestinal system, is subjected to the rigors of urinary, menstrual, and coital function.

Vascular supply: internal pudendal artery, and branches of the external pudendal vein

Nerve supply: perineal branch of the pudendal nerve.

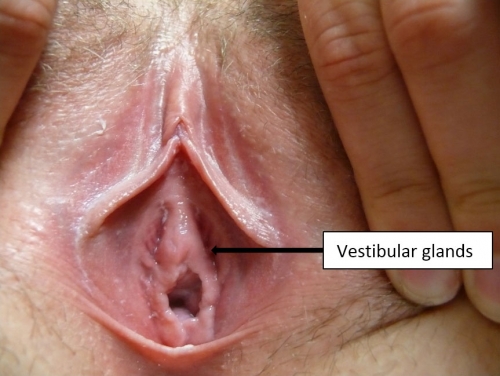

The greater glands of Bartholin

The greater glands of Bartholin are so-called because there are numerous other lesser glands throughout the vestibule. The Bartholin glands lie postero-laterally in relationship to the vaginal orifice, deep to the bulbospongiosis muscle. They are embedded in the erectile tissue of the clitoral (formerly called vestibular) bulbs at their posterior tip. The glands are branched tubulo-alveolar glands. They are not normally palpable, but can be readily palpated between finger and thumb when enlarged by inflammation.

The ducts are approximately 2 cm in length. The openings of the glands are often not visible; they exit external to the hymenal ring in the postero-lateral vestibule.29

The Bartholin glands produce a colorless, mucoid discharge with sexual arousal; the vast majority of natural lubrication with arousal comes as a plasma filtrate through the vaginal walls.

The lesser vestibular glands

The lesser vestibular glands are similar in structure to the greater vestibular glands and vary in number from one to more than 100.30 They are often seen as pits external to the hymenal ring and along the midline of the vestibule at 12 o’clock.

The paraurethral (Skene) glands described below are also lesser vestibular glands.

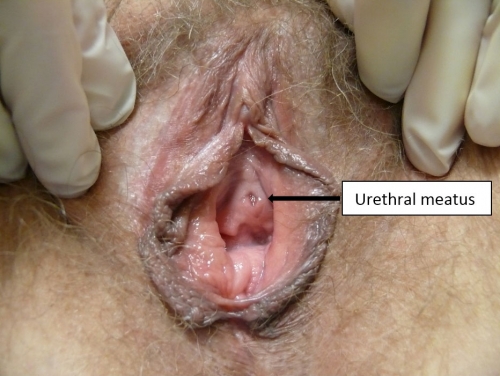

The urethral meatus

The urethral meatus is the small slit-like external opening of the urethra (Greek, ouros, drizzling rain) located in the vestibule between the vagina and clitoris. Its midline position may vary slightly anteriorly or posteriorly.

Just below the urethral meatus are the Skene glands (also known as the lesser vestibular glands, periurethral glands, paraurethral glands, U-spot, or female prostate). They drain mucus into the urethra and around the urethral opening. The epithelium of the vestibule merges with the transitional epithelium at the urethral meatus and at the duct openings of the paraurethral glands (Skene), the major vestibular glands (Bartholin), and the minor vestibular glands.31

Vascular supply: branches of the anterior internal iliac artery, the vesical and vaginal arteries. Venous drainage occurs via plexus around the urethra to vesicle plexus around the bladder neck and into the pudendal veins.

Nerve supply: pudendal nerve

The perineum and anus

These are not, strictly speaking, part of the vulva but, because of their proximity and frequent involvement in vulvovaginal conditions, mention is made.

The perineum (Greek, around evacuation) comprises the less hairy skin, muscle, and subcutaneous tissue that lie between the vaginal orifice and the anus. There is little subcutaneous fat, making the skin lie close to the underlying muscles. The perineum covers the perineal body, fibrous connective tissue that acts as the meeting point in mid-perineum for the bulbocaverosus, transverse perineal, and external anal sphincter muscles. The perineum’s varying length (0.5 to 2.5 in.) and suppleness influence the resistance it offers during the second stage of labor.

Vascular supply: perineal artery, arising from the pudendal. Venous drainage is through the internal pudendal vein.

Nerve supply: posterior labial nerve from the pudendal.

The anus (Latin, ring, circle) is the external opening of the rectum. It lies in the midline of the anal triangle, surrounded on each side by fat in the ischiorectal fossa. Fecal expulsion is controlled by sphincter muscles. The anus plays a role in sexuality, though attitudes towards anal sex vary.

Vascular supply: inferior rectal artery, branch of the pudendal, and inferior rectal vein, branch of the internal pudendal vein draining into the internal iliac vein.

Nerve supply: inferior rectal nerve, a branch of the pudendal.

Any chronic inflammatory condition can produce remarkable scarring of the vulva.32 When scarring alters the architecture of the vulva, the diagnoses of lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, severe atrophy, or previous trauma, must be considered. Abnormalities of architecture can develop with symptoms, or develop silently without symptoms. Treatment of the inflammatory process is imperative to control symptoms if present, prevent the development of pain, and to prevent further architectural changes and scarring.

Besides inflammation, other reasons for abnormal architecture include congenital absence, labial adhesions, hypoplasia or hypertrophy, neoplasm, treatment for neoplasm, surgery, trauma, edema, and female genital cutting. These conditions will not be reviewed here, but may be accessed through the Atlas.

Any neoplasm arising from the tissues of the vulva will distort architecture. Understanding normal architecture and normal variants will help in identifying neoplasms.

Note: In the photos below, the right side of the photo represents the left side of the patient, the left side of the photo represents the right side of the patient.

Changes of the mons and labia majora

Anatomical changes of the mons and labia majora, outside of normal variations having to do with size and genetic phenotype, are rare.

Changes of the labia minora

Hypertrophy of the labia minora may be present at birth, may be produced intentionally in some cultures, may occur from repeated traction associated with sexual practices, or may be idiopathic. Hypertrophied labia minora may be a source of local irritation, problems with genital hygiene, discomfort with walking, sitting, or sports activities. The hypertrophy may also be a source of discomfort with sexual intercourse. It is essential, however, to distinguish the discomfort of labial irritation from pain on touch in the vestibule (Annotation I, Q-tip test and pain mapping) or irritation from other sources.

Labia minora hypertrophy is generally described as protuberant labial tissue projecting beyond the labia majora. However, there is no consensus among gynecologists, pediatricians, or plastic surgeons regarding the use of objective clinical measurements to confirm the diagnosis.

In an early description of this condition, Friedrich classified labia minora as hypertrophic when the maximal width between the midline and the lateral free edge of the labia minora (when the labia were extended laterally by the examiner) measured greater than 5 cm.33

Others have proposed that the normal width of the labia minora should be up to four cm.34 Some feel that labial reduction should be offered to women (and fully developed adolescents) with persistent symptoms related to this anatomy.35

Variants of labia minora

Abnormalities of the labia minora are key indicators of disease, usually dermatosis. Meticulous questioning may uncover a history of itching or irritative symptoms when a woman claims to have been asymptomatic. (Quite frequently, women mention that they have had frequent yeast infections, which, in fact are symptoms relating to the dermatosis.) The inflammation may be active with whitening, erythema, erosions, ulcers, or fissures, or may be in remission or “burned out” with abnormal architecture such as labial loss, loss of prepuce or scarring to the glans with the epithelium normal in color, texture, and integrity. It is our opinion that women with architectural changes and the appearance of inactive disease be carefully monitored every six to twelve months since the natural history of lichen sclerosus and lichen planus is unknown. Further scarring may lead to dyspareunia and/or urinary compromise.

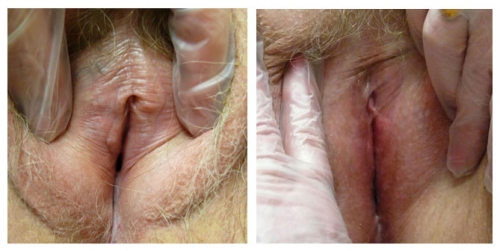

Variants or abnormalities include asymmetry, posterior flattening and resorption, unilateral or bilateral absence, agglutination of a portion of the labium to the interlabial sulcus, or “skip areas” where a portion of the labium is missing.

Details of the history and the remainder of the exam are essential to determining whether asymmetry reflects active pathology or not.

The relative symmetry of posterior flattening in the photo on the left brings into question normal variant versus abnormal resorption. On the right, bilateral resorption with adherence (agglutination) to the interlabial sulci, with whitening and anatomical changes of the peri-clitoral area, represent probable lichen sclerosus.

Left photo show loss of left labial tissue and loss of definition of the interlabial sulcus from 1 to 6:00 (with inflammation in the left vestibule); Right photo: There is symmetrical flattening of the labia minora from 2-10:00, with loss of the interlabial sulci. The fissure on the left and possible whitening posteriorly imply dermatosis.

Left photo: right labium missing from 6-9:00; left labium flattened from 1-2:00 and absent 2-6:00; Right photo: Anterior labia minora are lost and agglutinated bilaterally. There is periclitoral scarring with loss of the prepuce, and almost invisible clitoris. This is characteristic of lichen sclerosus.

Left photo: the labia minora, interlabial sulci, and prepuce have completely disappeared. The clitoris is almost invisible. Right photo: Labium minus flattened from 3-6:00 and right side absent from 6-10:00 with no definition of interlabial sulcus. Both of these women have lichen sclerosus.

Left photo: prepuce appears adherent to the glans. There is clear adherence of labial remnants to the interlabial sulci on both sides. Right photo: Complete loss of left side with almost complete loss on the right. Prepuce is losing definition.

Interlabial sulci will lose their definition if the labia minora are absent.

Abnormalities of the prepuce

Abnormalities of the prepuce include loss of the tissue from inflammation so that the glans clitoris is exposed, thickening and loss of mobility so that the glans is partially visualized, scarring to the glans in one area, or total fusion with visual obliteration of the glans. Lichen sclerosus or lichen planus are well known causes of such scarring,36 but often go unrecognized. The scarring of the prepuce and clitoris are mistakenly given the diagnosis of “phimosis”; without treatment, the inflammatory disease may progress, and scarring may increase. (lichen sclerosus and lichen planus).

Left photo: Featureless vulva with loss of prepuce, labia minora, and interlabial sulci. The glans is invisible. Right photo shows some loss of tissue of the prepuce and partial fusion to the glans as well as absence of the labia minora.

Left photo: loss of prepuce with exposure of the glans clitoris, loss of labia minora and interlabial sulci bilaterally. Right photo: abnormal periclitoral area with scarring of the prepuce, color and textural changes. Resorption of labial tissue bilaterally. Perineal scarring is present.

Abnormalities of the clitoris

The troughs between the medial margins of the labia majora and the lateral margins of the labia minora are subject to the disorders of partially keratinized skin, subtle hair follicles, sweat glands, and ectopic sebaceous glands. Whitening or erythema are common findings, fissuring may occur. Smegma is often present.

Absence of the clitoris, probably as a result of hypoplastic genital tubercles, has been reported at least once.37

Acquired clitoral enlargement can result from a variety of conditions.

A clitoral cyst (rare) or neoplasm can enlarge the paraclitoral area without a change in androgens. Recent research documented that tubular eccrine glands form a normal constituent of the sulcus between the glans and the prepuce. These glands may explain rare cysts and some pilonidal sinuses.[31] Smegmatic pseudocysts can result from adhesions of the clitoral hood in cases of lichen sclerosus. 38. Imaging by ultrasound or MRI is helpful to gain information regarding size and location. Excision is usually necessary by a surgeon skilled with clitoral procedures, often a gynecologic oncologist.

Note loss of periclitoral architecture and labia minora, with pallor and erythema.

Exogenous androgen exposure from anabolic steroids, DHEA, or testosterone, may enlarge the glans. Women who use testosterone for therapeutic reasons (treating low libido, averting osteoporosis, or as part of an anti-depressant regimen), may also experience some enlargement of the clitoris although the dosages warranted for these conditions are much lower. Although the treatment of choice for lichen sclerosus is the ultrapotent steroid clobetasol, topical testosterone continues to be prescribed. If there is clitoral enlargement from exogenous androgens, discontinuing the androgen is indicated.

Right photo: top-normal size glans clitoris with complete resorption of the clitoris in 60 year old woman with lichen sclerosus treated with topical testosterone. Left photo: Note resorption of the prepuce, mild hypertrophy of the glans, almost total loss of labia minora, whitening of perineum. This, too, is lichen sclerosus.

Both photos represent women who were treated for biopsy-proven lichen sclerosus with testosterone.

Endogenous androgen imbalance or excess: In women, mild virilization, the presence of hirsutism, acne, deepening of the voice, frontal (or crown) balding, increased muscle mass, and/or clitoromegaly indicate the presence of moderate androgen excess arising from stromal hyperthecosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, ovarian or adrenal neoplasm, or adrenal hyperplasia. An endocrine work-up is necessary.

Androgen receptor insensitivity (formerly called incomplete testicular feminization) is seen in patients who have an overall female phenotype with female breast development and predominantly female external genitalia except for posterior labial fusion and/or clitoromegaly. Consult with a reproduction endocrinologist is indicated.

Sometimes there may be no obvious or hormonal reason for clitoromegaly after a workup.

Architectural alterations of the vestibule

Papillae: These are discrete tubular projections with rounded tips, considered to be normal variants.

Note prominent tube-shaped fronds on the patient’s left. This is a normal variant.

Synechiae: Synechial formation anteriorly or posteriorly, usually from scarring vulvitis such as lichen sclerosus or lichen planus, restricts the vestibule and lessens the introital opening.

Left photo: focal synechial bridge in patient with loss of prepuce and labia minora with pallor of lichen sclerosus. Right photo: anterior and posterior synechial bridges, perineal whitening, loss of labia minora bilaterally, and periclitoral scarring.

The inflammatory condition must be treated, usually with an ultra-potent steroid such as clobetasol applied in a thin film topically, nightly for 30 days and then maintained with twice-weekly use. Then scarring affecting the introitus may be addressed. Work with progressive sizes of dilators inserted for 20-30 minutes at least three times weekly may gain some added space. (Annotation D: Tolerance of genital exam). Physical therapy to the pelvic floor may be necessary to overcome tightening and secondary vaginismus in response to pain.

Surgical division of labial synechiae with cold knife or by laser, in our experience, yields a high rate of recurrence, despite attempts at prevention with such modalities as Inteceed anti-adhesion material, Dermabond coating, and mechanical separation with Vaseline gauze. Some of our patients have had benefit from a post-surgical routine of ongoing control of the dermatosis with an ultrapotent steroid topically twice a week, adequate local estrogen with estradiol cream three times weekly to the vestibule and topical barrier to adhesion with vaseline or zinc oxide applied three times a day. In addition, 20-30 minutes of dilator use (Annotation D: Patient tolerance for exam, dilators) or intercourse three times weekly maintains patency of the introitus. On-going monitoring every 3-4 months is important. This challenging regimen has to be maintained indefinitely.

Perineoplasty with vaginal advancement may be necessary for comfortable intercourse if division of synechiae and/or dilator therapy fail.

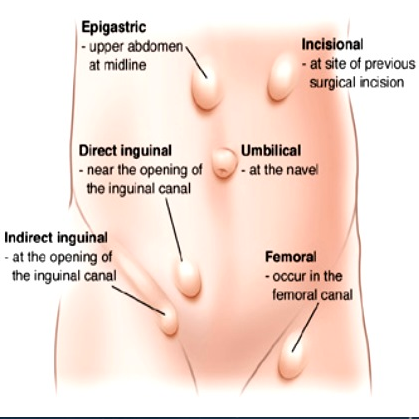

Hernia

Indirect inguinal hernia: In the female, the round ligament is attached to the uterus near the origin of the fallopian tube and a small evagination of parietal peritoneum accompanies the round ligament through the inguinal ring into the inguinal canal. This small evagination of peritoneum is the canal of Nuck. The canal normally undergoes complete obliteration during the first year of life. Failure of complete obliteration results in an indirect inguinal hernia. If the opening is small and only fluid accumulates, a hydrocele of the Canal of Nuck results. The indirect hernia or hydrocele of the Canal of Nuck enlarges the labium majus. Indirect inguinal hernia is more common in men than women; if suspected, refer for surgical evaluation.

Direct inguinal hernia: A direct hernia occurs medial to the indirect through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal above and medial to the pubic tubercle. These hernias usually occur as the abdominal wall weakens in later life and they create a bulge in the groin fold. Women seldom have direct inguinal herniae; if there is suspicion, refer for surgical evaluation.

Femoral hernia: A femoral hernia descends in the femoral canal containing the artery, vein and nerve located below and lateral to the pubic tubercle. With this hernia, a bulge would be noted in the mid-thigh inferior to the inguinal crease.39 Surgical referral is necessary.

Pudendal enterocele: Pudendal enterocele, or pudendal hernia, represents a descent of the peritoneum (enterocele) or viscera (bladder and small or large intestine) through a defect in the urogenital diaphragm anterior to the transverse perineal muscle and exiting into the labium. Pudendal hernia has also been labeled labial hernia, anterior perineal hernia, and pudendal enterocele. These defects are rare, with less than one hundred cases in the literature, and follow hysterectomy or vaginal surgery. They present as painless bulges. They are diagnosed by imaging and are repaired surgically.40

References

- Andrikpoulou M, Michala L. Creighton SM, Liao LM. The normal vulva in medical textbooks. J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;33:648-50

- Edwards, L, Lynch PJ, eds. Genital Dermatology Atlas, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins/ Wolters Kluwer; 2011: 1-5

- Kreklau A, Vaz F, Oehme R, et al. Measurements of a ‘normal vulva’ in women aged 15-84: a cross-sectional prospective single-centre study. BJOG 2018; https:/doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15416

- Basran M, Kosif R, Bayar U, Civelek B. Characteristics of external genitalia in pre- and postmenopausal women. Climacteric 2008;11:416-21

- Kreklau A, Vaz F, Oehme R, et al. Measurements of a ‘normal vulva’ in women aged 15-84: a cross-sectional prospective single-centre study. BJOG 2018; https:/doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15416

- Kreklau A. Viaz I, Oehme F, Strub F. Brechbuhl R, Christmann C, Gunthert A. Measurements of a ‘normal vulva’ in women aged 15-84: a cross sectional prospective single-centre study. BJOG;2018; https://doi.org/10.1111//1471-0528.15387.

- Kreklau A. Viaz I, Oehme F, Strub F. Brechbuhl R, Christmann C, Gunthert A. Measurements of a ‘normal vulva’ in women aged 15-84: a cross sectional prospective single-centre study. BJOG;2018; https://doi.org/10.1111//1471-0528.15387.

- Kreklau A. Viaz I, Oehme F, Strub F. Brechbuhl R, Christmann C, Gunthert A. Measurements of a ‘normal vulva’ in women aged 15-84: a cross sectional prospective single-centre study. BJOG;2018; https://doi.org/10.1111//1471-0528.15387.

- Preti M, Viera Baptista P, Digesu GA, et al. The Clinical role of LASER for Vulvar and Vaginal Treatments in Gynecology and Female Urology: An ICS/ISSVD Best Practice Consensus Document. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2019 Apr;23(2): 151-160. doing:10.1097/.0000000000000462. PPMID 30789385.

- Sillman FH, Muto MG. The vulva, in Kistner’s Gynecology, KJ Ryan, RS Berkowitz, RL Barbieri, eds. St Louis. Mosby; 1995: 50

- Sillman FH, Muto MG. The vulva, in Kistner’s Gynecology, KJ Ryan, RS Berkowitz, RL Barbieri, eds. St Louis. Mosby; 1995: 50

- Sillman FH, Muto MG. The vulva, in Kistner’s Gynecology, KJ Ryan, RS Berkowitz, RL Barbieri, eds. St Louis. Mosby; 1995: 50

- Neill SM, Lewis FM. Basics of vulval embryology, anatomy and physiology. In:Ridley’s The Vulva. Neill SM, Lewis FM, eds., Oxford, England, Wiley-Blackwell; 2009: 14

- Munarriz R, Talakoub L, Kuohung W, et al. The prevalence of phimosis of the clitoris in women presenting to the sexual dysfunction clinics: Lack of correlation to disorders of desire, arousal, and orgasm. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002; 28(s):181-185

- Neill SM, Lewis FM. Basics of vulval embryology, anatomy and physiology. In: Neill SM, Lewis FM, eds. The Vulva, 3rd ed, Chichester, West Sussex, UK, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, 14.

- Sillman FH, Muto MG. The vulva, in Kistner’s Gynecology, KJ Ryan, RS Berkowitz, RL Barbieri, eds. St Louis. Mosby; 1995: 50

- O’Connell HE, Kalavampara V. Sanjeeva V, Hutson JM. Anatomy of the Clitoris. J Urol, 2005;174(4):1189-1195

- Yang CC, Cold CJ, Yilmaz U, Maravilla KR. Sexually responsive vascular tissue of the vulva. British Journal of Urology. 2006:97:766-772

- Schlosser BJ, Mirowski GW. Approach to the patient with vulvovaginal complaints. Dermatol Ther. 2010; 23:438-448.

- O’Connell HE, Hutson FM, Anderson CR et al. Anatomical relationship between urethra and clitoris. The Journal of Urology. 1998;159:1892.

- Puppo V. Clitoral anatomy in nulliparous, healthy, premenopausal volunteers using unenhanced magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of Urology. 2006;175:790-791

- Hines TM. The G-spot: a modern gynecologic myth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:359-362

- O’Connell HE, Snajeevan KV. Anatomy of female genitalia. In Women’s Sexual function and Dysfunction, Goldstein I, Meston CM, Davis SR, Triash AM, eds. London: Taylor & Francis; 2006: 109

- Lloyd, J, Crouch, NS, Minto, CL, et al. Female genital appearance: “normality” unfolds. BJOG. 2005; 112: 643.

- Verkauf, BS, Von Thron, J, O’Brien, WF. Clitoral size in normal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 80: 41.

- Tagatz, GE, Kopher, RA, Nagel, TC, Okagaki, T. The clitoral index: A bioassay of androgenic stimulation. Obstet Gynecol. 1979; 54: 562.

- Wilkinson EJ, Stone IK. Atlas of Vulvar Disease, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins/ Wolters Kluwer, 2008.

- O’Connell HE, Kalavampara V, Sanjeevan V, and Hutson JM. Anatomy of the clitoris. J Urol. 2005; 174: 1189-1195.

- Wilkinson EJ, Stone IK. Atlas of Vulvar Disease, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

- Robboy SJ, Ross JS, Prat J, et al. Urogenital sinus origin of mucinous and ciliated cysts of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1978; 51(3):347-351.

- Wilkinson EJ, Stone IK. Atlas of Vulvar Disease, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

- Edwards L. Genital Dermatology Atlas. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004: 97.

- Friedrich EG. Vulvar Disease, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders, 1983.

- Rouzier R, Louis-Sylvestre C, Paniel BJ, et al. Hypertrophy of labia minora: experience with 163 reductions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 182: 35-40.

- Reddy J, Laufer MR. Hypertrophic labia minora. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010; 23:3-6.

- McPerson T, Cooper S. Vulval lichen sclerosus and lichen planus. Dermatol Ther. 2010; 23: 523-532.

- Falk HC, Hyman AB. Congenital absence of the clitoris: a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1971;38: 269-271.

- Funaro d. Lichen sclerosus: a review and paractical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004: 17;28-37.

- Symes B. TheCanalofNuck: threeherniasandahydrocele. ASUM Ultrasound Bulletin May 2008 (2):4-8.

- Zimmern PE, Miyazaki F. Pudendal enterocele with bladder involvement. Urology. 1994; 44(6) 918-921.