Introduction

Sexual health is as integral a part of overall health as mental, physical, social, psychological, and spiritual health, and is becoming better accepted as a fundamental part of healthcare. It is therefore essential to understand and address normal changes to sexual function throughout the lifespan, sexual dysfunction, and health related sexual sequelae.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexuality as “a central aspect of being human throughout life, [encompassing] sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction…. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors.” 1

Sexuality is often a positive and important aspect of people’s lives; however, for some it is more complex. As the WHO states, how one’s sexuality is experienced can be influenced and affected by multiple factors such as upbringing, life stage, beliefs, education, experience, trauma, health and physical factors including pain. Vulvovaginal pain can disrupt sexual health and function in significant ways. Genital pain can be disruptive to sexual experience in and of itself. It can also contribute to disruption in other parts of people’s sex lives, including desire, arousal, orgasm, intimacy, self-image, and relationships. However, even for those for whom sexual activity is painful, sexuality and sexual intimacy can remain extremely important. Although sexuality and sexual function can be highly stigmatized and difficult for both patients and providers to discuss, it is incumbent upon providers to build skills to address this area of patients’/clients’ health. A biopsychosocial approach to evaluation and treatment of vulvovaginal pain utilizing a multidisciplinary team is essential.

This section of the V Disorders website explores vulvovaginal pain and sexuality. To understand sexuality in the context of vulvovaginal pain it is important to appreciate an overview of sexuality including physiology, models of sexual response, and categories of sexual dysfunction. With that foundational understanding established, this section then examines the impact of vulvovaginal pain on sexuality through a broad lens and goes on to discuss treatment approaches. Finally, this section closes by advocating a universal trauma-informed approach to care.

Typical vulvovaginal sexual physiology

Genital sexual response for people with vulvas and vaginas consists of arousal-related changes of the vulvar and vaginal tissues often leading to orgasm. Orchestration of this complex process involves cognitive and psychological factors, neuroendocrine factors, central and peripheral neurophysiological pathways, vascular physiology, and sex steroid hormone regulation.

For detail on mechanisms of sexual physiology, please click “read more” below.

In the last few decades, more sophisticated technology than previously available has yielded substantial advances in the understanding of the physiological aspects of normal female sexual function and dysfunction, allowing less dependence on animal models. Technology, including neuro-imaging has been able to identify areas of the brain specific to arousal and orgasmic responses. Research on peripheral pathways and the interaction between central and peripheral mechanisms has provided a better understanding of female desire, arousal, and orgasm.2

The following is a brief description of central physiology as well as the physiology of peripheral arousal and orgasm. Anatomy and physiology of the vulva and vagina are described throughout the website.

Central nervous system-related physiology of sexual function

The nervous system produces an array of cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioral responses critical to sexual function. These are coordinated and controlled by the cerebral cortex, which interprets what sensations are to be perceived as sexual, and issues commands to the rest of the nervous system.

Mechanical stimulation of external genitalia by pressure or touch excites sensors within the skin, mucosa, and subcutaneous tissue. The excitation travels through the sensory nerves of the lower abdomen to the spinal cord, where it elicits both sympathetic and parasympathetic reflexes: blood flow to the genitals, glandular secretion, and smooth muscle contraction in sexual organs. The cerebral cortex and limbic system excite the hypothalamus as well as other autonomic nervous system controls, so that spinal cord reflexes accompanying sexual activity are even more stimulated in a self-propagating cycle.

Sexual response depends on the neuroendocrine environment for integrity and sensitivity. Simultaneously, the sensory responses of the genitals in response to touch, as well as to the response of engorgement, travel up the spinal cord to the brain, sensory cortex, and limbic system eliciting the perception and reaction of pleasure.3

Physiology of peripheral arousal

Sexual arousal of the vulva and vagina is described as a combination of objective and subjective signs. Objective signs include vulvar swelling, vaginal lubrication, heavy breathing, and increased sensitivity of the genitalia. These combine with the subjective experience of feeling pleasure and excitement.4

Increased blood flow to the genitals is the hallmark of sexual arousal. It results from sensory stimulation as well as central nervous activation. The increased blood flow culminates in a series of vasocongestive and neuromuscular events leading to physiological changes.5

In vivo MR imaging of genitalia, combined with gross and histologic examinations of cadaveric specimens, have demonstrated six vascular compartments comprising the external female genitalia, the clitoris, clitoral bulbs, labia minora, urethra, and vestibule/vagina.6 The clitoris and the clitoral bulbs represent erectile tissue with the greatest volume change with engorgement during sexual arousal compared with non-erectile tissues.7

External Genitalia in arousal

Labia

During sexual arousal, the blood flow to the labia is increased, leading to engorgement and lubrication. The size of the labia minora increases by as much as two to threefold,8 and their sensitivity to touch is augmented. Because the labia minora represent the entry way into the vagina, their lubrication (discussed below) is essential for penile, digital, or sex toy penetration and thrusting without pain.9

Clitoris

In the unaroused state, the clitoral vasculature has a high sympathetically-mediated tone. The vessels are mainly closed,10 but demonstrate intermittent opening and closing, called vasomotion,11 based on local tissue needs.

The nerve supply to the clitoris occurs through VIPergic nerves releasing vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) that dilates the arterial supply,12 and nitric oxide (NO), which promotes relaxation of the smooth muscle of the cavernous sinuses.13 The two vasodilator neurotransmitters, combined with the central reduction of sympathetic tone, create increased blood flow to the clitoris as the trabecular smooth muscles relax and the intracavernous pressure rises.14 The body of the clitoris has a single layer of tough, fibrous tissue (tunica albuginea) between its connective tissue tunica and the erectile tissue (unlike the penis with a bilaminar structure), so that it becomes swollen or tumescent, but not rigid with true “erection” even when its vasculature is full.15

Internal Genitalia in arousal

Urethra

The female urethra, 4 cm in length, has walls containing blood-filled venous sinuses; triangular-shaped paracrine cells in the lining of the urethra are believed to have mechanoreceptor properties and to contain serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine). Serotonin is known to power the sensitivity of nerve endings.16 Stretching of the urethra during coitus17 or during digital stimulation of the anterior wall may activate the mechanoreceptors to release serotonin, which sensitizes the nerve endings in the urethra, creating pleasurable sensations,18 and transforming the urinary structure into a sexual one.19

Vagina: vaginal microcirculation

A number of different nerve fibers supply the vaginal capillary microcirculation; the exact functions of the various nerve fibers are not yet confirmed.20 It is known that multiple nerve related products influence vaginal microcirculation: adrenergic, cholinergic, and VIPergic nerve secretions, neuropeptide substance P (a sensory transmitter), neuropeptide Y (a vasonconstrictor), calcitonin gene-related peptide (a possible sensory transmitter and a peptide influencing capillary permeability ) and NO.21

Like other microcirculations, vaginal capillaries in the basal state are closed by contraction of the pre-capillary sphincters; the surface pO2 of the vagina wall is thus basally at a low, hypoxic level.22 When the local area around one of these capillaries becomes hypoxic, the released metabolites (pCO2, lactic acid,K+, adenosine triphosphate ATP) cause pre-capillary sphincter relaxation and the supplied capillaries to open up, washing away the metabolites and refreshing the local area with oxygen and nutrients. This intermittency of the microcirculation is known, as with the clitoris, as vasomotion.23 The degree of vaginal vasomotion is a sensitive and useful index of genital arousal in the research setting. Thus, during basal conditions, a high vasomotor tone of the arterial supply through central sympathetic activation and a high level of vasomotion keeps the blood flow to the vagina at minimal levels.

At the beginning of sexual arousal, high sympathetic vasomotor tone and vasomotion minimize the blood supply to the vagina. Within seconds of acceptable or consensual sexual stimulus, there is reduction of central sympathetic tone and enhancement of the arterial supply through the action of released neuronal VIP and NO via the sacral anterior nerve root;24 as more opened capillaries are recruited, vasomotion decreases.25 As rapid recruitment of capillaries maximizes, the vagina becomes fully vasocongested (along with the labia and clitoris), and vasomotion disappears. The woman will subjectively perceive pelvic fullness and congestion, and reactive desire to dissipate the congestion with orgasm. Dissipation of congestion is very slow, even with orgasm that facilitates the action. A single orgasm does not usually cause complete dissipation.26 Orgasms, however, are the natural and pleasurable means to ameliorate the pelvic discomfort.

In addition, slow oscillations in vaginal blood flow have been documented, both in rats and humans, as a marker of sexual arousal.27 These oscillations appear independent of vaginal vasocongestion. The slow oscillations in vaginal blood flow have been correlated with subjective physiological arousal in healthy human volunteers, but display diminished responsiveness in women with female sexual arousal disorder (FSAD).28

Vagina: arousal and lubrication

In the sexually aroused vagina, capillary engorgement with blood leads to increased capillary hydrostatic pressure and transudation of plasma (ultrafiltrate) into the interstitial space around the blood vessels. The transudate fills up the interstitial space and exudes through and between the cells of vaginal epithelium to the surface wall of the vagina as vaginal lubrication. The final fluid is a modified plasma filtrate because the cells of the vagina can transfer Na+ ions vectorially from the lumen back into the blood29 and add K+ ions by secretion and cell shedding.30 Throughout the menstrual cycle, basal vaginal fluid has a higher K+ and a lower Na+ than plasma.31 In contrast, the arousal transudate has a much higher Na+ concentration than the basal fluid, approaching that of plasma.32 On cessation of sexual arousal, the vaginal Na+, together with osmotically drawn fluid, is transferred back into the blood, thus re-setting the vagina to the basal “just moist” condition.33

Vagina: anterior wall, possibly erotic structures

With the stimulation of deep pressure, the anterior vaginal wall is known to generate a more sexually pleasurable feeling than either of the lateral or posterior vaginal walls.34 The urethra, with its potential for providing pleasurable sensations, is located in the anterior vaginal wall. In addition, there is the controversial Grafenberg spot (G-Spot) a site on the anterior wall of the vagina that can also be stimulated by deep pressure to engorge, protrude into the vaginal lumen, and facilitate orgasm in women.35 Halban’s fascia represents a layer of fascia between the bladder and the anterior wall of the vagina that has been suggested to elicit highly pleasurable sensations leading to orgasm when adequately pressure-stimulated.36

Cervix and uterus in arousal

Although many studies have been done, the role of both the cervix and the uterus in sexual arousal has not been clearly defined.37 Uterine contractions are reported to occur during high levels of sexual excitement and at orgasm.38

Nipple and breast stimulation in arousal

Enhancement of sexual arousal by female nipple/breast stimulation has not been well studied. One study showed that the majority of the women in the sample demonstrated that stimulation of nipples/ breasts caused or enhanced their sexual arousal. 80 percent of the women agreed that when sexually aroused, stimulation of the nipples further increased their arousal.39

Physiology of orgasm

Orgasm is defined as a variable, transient, peak sensation of intense pleasure, creating an altered state of consciousness. It is usually accompanied by involuntary, rhythmic contractions of the pelvic striated circumvaginal musculature, with concomitant uterine and anal contractions, and myotonia that resolves the sexually induced vasocongestion (sometimes only partially). Orgasm is usually associated with a sense of well-being and contentment.40

Striated pelvic floor muscle changes during orgasm

Pelvic floor muscles are classified as superficial muscles (the urogenital diaphragm, including the ischiocavernosus, the bulbocavernosus, and the deep and transverse perinei) and the deep muscles, often described as the “pelvic diaphragm,” (ischiococcygeus and the levator ani).41 Annotation L The Pelvic Floor.

The pudendal nerve pathway with both afferent (sensory) fibers and efferent (motor) fibers is responsible for the generation of the rhythmic contractions of these muscles that occur in most women during orgasm. The number of the contractions varies with the duration and intensity of the orgasm.42

The purpose of these pelvic floor muscle contractions in women is not clearly established; suggested functions include female ejaculation, pleasure, restoration of vasocongested pelvic tissue to its basal state, and stimulation of the male.43

In the past, some experts have considered pelvic floor muscle contractions as an intrinsic and indispensable part of orgasm,44 45 while others have not.46 47 More recently, pelvic floor dysfunction has been linked to problems in sexual function.

In general, hypoactivity of the muscles (low tone) may lead to lack of pleasure during sexual intercourse and orgasm; in contrast, hyperactivity (high tone) may be part of the pathology linked to the sexual pain disorders.48 49

Clitoral stimulation in relation to orgasm

Clitoral stimulation is the main source of sensory input for eliciting orgasm.50 51 In female cats, the identified pathway shows that afferent (sensory) fibers from the clitoris travel exclusively in the pudendal nerve.52 While it is hypothesized that coital orgasm is triggered by stimulation of the internal genital organs–the vagina, cervix and uterus–the neurophysiologic support for the coital orgasm is less clear than the pudendal pathway for clitoral orgasm.53 Orgasm can be obtained by stimulation of the periurethral glans area, mons, breasts/nipples, by mental imagery or fantasy, or even by hypnotic suggestion. Orgasm is known to occur during sleep.54

Vagina in orgasm

The vagina is surrounded by the powerful pelvic striated musculature. It is innervated by VIPergic nerves that release a dilator of blood vessels, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and a relaxer of vaginal wall smooth muscles, nitric oxide (NO). At orgasm, the contractions of the striated pelvic floor muscles impinge on the vagina causing passive increases in its intraluminal pressure. No study has measured the vaginal smooth muscle and striated pelvic floor muscle at the same time during orgasm,55 making the contribution of muscle groups unclear.

Linking the degree of vaginal muscle contraction activity to the pleasure felt during the contraction activity has not been successful. While Masters and Johnson, reported that the stronger the orgasm, the greater was the number of contractions experienced, a study utilizing recordings of the intraluminal vaginal pressure during orgasm did not show any linkage between the orgasmic contractions and the intensity of pleasure.56

Uterus in orgasm

The function of contractile activity of the uterus at orgasm is also not understood. Besides Masters and Johnson’s work proposing that uterine contractions were expulsive and not involved in “up-sucking” material from the vagina, few measurements of this uterine activity during orgasm have been documented to date.57 58

Cervix in orgasm

A minimal amount of dilatation of the cervical os occurs immediately after orgasm, persisting for 20–30 minutes,59 allowing spermatozoal migration through the endocervical canal. Although the mechanism for this dilatation has not been studied, the cervix’s second highest concentration of VIP in the genital tract makes it possible that its relaxant action on the sparse smooth muscle present could be involved. 60

Rectal sphincter and pressure in orgasm

There is contraction of the rectal sphincter at orgasm, similar to the contractions of the vagina.61 Fluctuations in rectal pressure changes during orgasm have been studied with a spectrum analyzer that is capable of measuring the amplitude versus frequency of mechanical contraction. In roughly 90% of the orgasms induced in normal women by clitoral masturbation undertaken by their partners, alpha band (8–13 Hz) modifications may be identified.62

Models of Female Sexual Response

The concept of a sexual response cycle was first put forward by pioneer sexuality researchers, William Masters and Virginia Johnson, in 1966. Since then, the understanding and description of the female sexual response has evolved and become more complex, based on ongoing research, enabling better treatments and interventions.

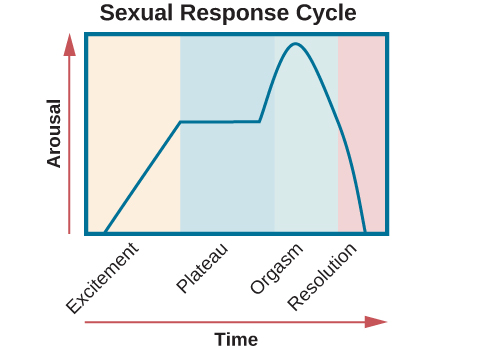

Masters and Johnson’s human sexual response cycle was based on physiological measurements of sexual response in thousands of human subjects. This four stage model depicted a linear progression,63 starting with the excitement phase and moving successively through the plateau, orgasmic, and resolution phases. This model made no distinction between male and female sexual response, and also did not include the concept of desire.

Figure 1: Masters and Johnson Model

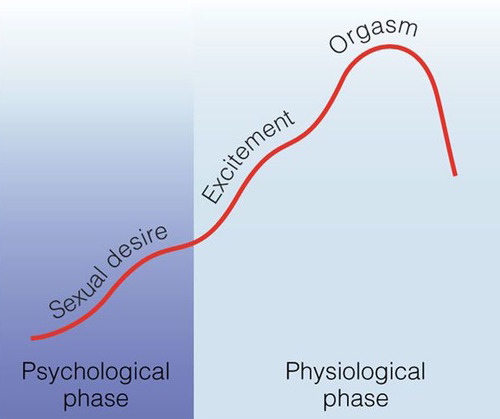

In the 1970’s the Masters and Johnson model was restructured and simplified by psychologist and psychiatrist, Helen Singer Kaplan,64 enhancing its usefulness for working with patients in sex therapy. Kaplan added a desire phase at the beginning of the cycle, radically reframing our understanding of sexuality by adding psychological and relational elements to the physiological responses studied by Masters and Johnson. She also simplified the cycle to a three phase (still linear) model of desire, arousal, and orgasm. Both the Masters and Johnson and Kaplan models however, assumed that women’s sexual response paralleled the male sexual response.

Figure 2: Helen Singer Kaplan Model

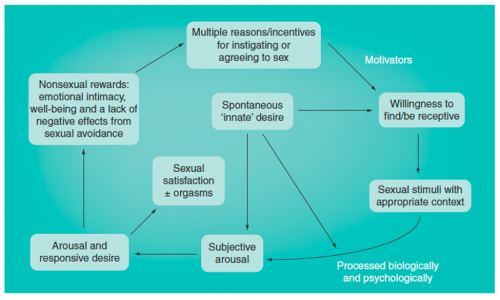

In the early 2000’s researcher Rosemary Basson further evolved our understanding of the female experience of sexual response.65 Differentiating it from the male model, Basson’s representation is circular and depicts the phases of sexual response as overlapping and varying. This model reflects the fact that individuals do not all respond in the same way, and each particular individual may have varying responses across sexual experiences. The fluidity of normal sexual function, and the underlying complexity of female sexual experiences are clarified and depicted in the diagram below.

Figure 3: Human sex response cycle66

In this model, a sexual episode can begin at any point of the response cycle. For example, simply wanting to feel emotional closeness to a partner can lead to sexual stimulation, possibly followed by arousal, which then may lead to desire. If this closeness does occur, sexual motivation may increase; if it does not occur, motivation may lessen. This model introduces and explores the concept of responsive desire as opposed to spontaneous desire.

In many cases, orgasm (represented by “emotional and physical satisfaction” in the model) is not essential to feelings of pleasure and gratification, contrary to the goal-oriented expectation of orgasm with every sexual encounter. At times, a more receptive role may be taken, with desire and arousal arising only after sexual stimulation occurs.67 68

Conversely, some women have intercourse or penetration without experiencing desire, arousal, or orgasm and may not enter the response cycle at all.

Models of the human sexual response cycle continue to evolve in the literature. Sex therapist and educator, Lenore Tiefer, argues that these models are misleading and flawed in that they segment and define sexuality in ways that distort both scientifically and clinically.69

Overall, the sexual response cycle is a complex system that we are continuing to understand and elucidate. Relationship discord, power struggles, infidelity, poor body image, sexual shame, cultural and religious expectations, history of sexual trauma, and other interpersonal and intrapersonal issues can have a powerful impact on sexual expression and sexual function. We are also just beginning to research the similarities and differences in sexual response for transgender, non-binary and queer individuals which will likely continue to cause review of these models and reflect the limitations of using a model as a template to understand human sexual response.

Classifications of female sexual dysfunction

While this section of the website focuses on vulvovaginal pain, it is important to have an understanding of other types of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) as they often co-occur. Concerns about sexual function are common and include problems with desire, arousal, and orgasm, as well as pain with sexual activity. When these concerns cause significant distress they may meet criteria for a diagnosis of sexual dysfunction disorder. Worldwide, approximately 40% of women report sexual problems and one out of eight women (12%) experience a sexual problem associated with personal or interpersonal distress.70 71 72 73 74 75

The subjective element of personal distress is essential to diagnose a sexual disorder. Variations in sexual function that are not distressing for the patient or client, should not be pathologized by the clinician. Sexual dysfunction can be lifelong or acquired. To be considered dysfunction, the concern must be recurrent and persistent. Just as sexuality is multifaceted and complex, the etiology of sexual dysfunction is also often multifactorial and can include relationship concerns, side effects of medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective norepinephrin re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs), antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines, psychological diagnoses such as anxiety or depression, medical or physical conditions such as arthritis, endometriosis, cancer diagnosis and treatment, or genitourinary syndrome of menopause, history of sexual or physical abuse, fatigue and more.76

While types of FSD are separated for diagnosis and management, it is common for them to occur concurrently and they may influence each other. For example, desire may be reduced when pain is anticipated, experiencing pain may disrupt arousal and pleasure, and orgasm may be harder to achieve in the presence of pain.

Sexual dysfunctions have been classified and defined in different ways by different bodies. Widely used systems and definitions include those of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the 4th International Consultation on Sexual Medicine (ICSM), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Diagnosis is achieved through medical and sexual history as well as physical exam when appropriate. What follows below is largely based on the DSM-5.77 78 79

- Female sexual interest/arousal disorder: The DSM-5 characterizes female sexual interest/arousal disorder by the presence of significantly reduced or absent sexual interest/arousal. Manifestations can include subjective and objective factors such as decreased interest in sexual activity, decreased sexual thoughts or fantasies, decreased initiation of sexual activity or receptivity to partner’s initiation, absent or decreased sexual excitement or pleasure with sexual activity, decreased arousal from sexual or erotic cues, and decreased sensations during sexual encounters. This category includes the previous DSM categories of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and female sexual arousal disorder. It should be noted that the 4th International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015 maintains desire and arousal disorders as separate and distinct categories.80 81

- While not present in the DSM-5, an additional arousal based disorder is persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD) characterized by persistent or recurrent, unwanted or intrusive, distressing feelings of genital arousal or being on the verge of orgasm, not associated with sexual interest, thought or fantasies. The arousal is unrelieved by orgasm and the feelings of arousal can persist for hours or days. Treatment can be challenging and the condition unrelenting and therefore associated with significant distress, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.82 The consensus statement is available here: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) Review of Epidemiology and Pathophysiology, and a Consensus Nomenclature and Process of Care for the Management of Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder/Genito-Pelvic Dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD).

- Female orgasmic disorder: The DSM-5 characterizes female orgasmic disorder by delay, infrequency or absence of orgasms and/or reduced intensity of orgasmic sensations.

- Genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder: The DSM-5 characterizes genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder as persistent or recurrent difficulties with vaginal penetration during intercourse, marked vulvovaginal or pelvic pain during vaginal intercourse or penetration attempts, marked fear or anxiety about vulvovaginal or pelvic pain in anticipation of, during, or as a result of vaginal penetration, and/or marked tensing or tightening of the pelvic floor muscles during attempted vaginal penetration. This category includes the previous categories of dyspareunia and vaginismus.

Dyspareunia can be defined as painful intercourse. Vaginismus is defined as involuntary spasm of muscles around the vagina that prevents or interferes with vaginal penetration. While not present in the DSM-5, the ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS developed consensus terminology in 2015 to further classify vulvar pain.83 This terminology differentiates vulvar pain caused by specific disorders from the disorder of vulvodynia, which can be defined as vulvar pain of at least 3 month’s duration, without clear identifiable cause, which may have potential associated factors.

Table 1: 2015 Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain

A. Vulvar pain caused by a specific disorder*

- Infectious (e.g. recurrent candidiasis, herpes)

- Inflammatory (e.g. lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, immunobullous disorders)

- Neoplastic (e.g. Paget disease, squamous cell carcinoma)

- Neurologic (e.g. post-herpetic neuralgia, nerve compression or injury, neuroma)

- Trauma (e.g. female genital cutting, obstetrical)

- Iatrogenic (e.g. post-operative, chemotherapy, radiation)

- Hormonal deficiencies (e.g. genito-urinary syndrome of menopause [vulvo-vaginal atrophy], lactational amenorrhea

B. Vulvodynia – Vulvar pain of at least 3 months duration, without clear identifiable cause, which may have potential associated factors

Descriptors: (Note: these are pertinent to any vulvovaginal complaint)

- Localized (e.g. vestibulodynia, clitorodynia) or Generalized or Mixed (Localized and Generalized)

- Provoked (e.g. insertional, contact) or Spontaneous or Mixed (Provoked andSpontaneous)

- Onset (primary or secondary)

- Temporal pattern (intermittent, persistent, constant, immediate, delayed)

*Women may have both a specific disorder (e.g. lichen sclerosus) and vulvodynia

Table 2: 2015 Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain – Appendix: Potential Factors Associated with Vulvodynia*

- Co-morbidities and other pain syndromes (e.g. painful bladder syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular disorder) [Level of evidence 2a]

- Genetics [Level of evidence 2b]

- Hormonal factors (e.g. pharmacologically induced) [Level of evidence 2b]

- Inflammation [Level of evidence 2b]

- Musculoskeletal (e.g. pelvic muscle overactivity, myofascial, biomechanical) [Level ofevidence 2b]

- Neurologic mechanisms:

- Central (spine, brain) [Level of evidence 2b]

- Peripheral [Level of evidence 2b]

- Neuroproliferation [Level of evidence 2b]

- Psychosocial factors (e.g. mood, interpersonal, coping, role, sexual function) [Level of evidence 2b]

- Structural defects (e.g. perineal descent) [Level of evidence 2b]

*The factors are ranked by alphabetical order

Impact of Vulvovaginal Pain on Sexuality

Masters and Johnson reported many years ago that it takes only a few episodes of sexual pain before a person’s focus changes from pleasure to anticipation of pain.84

Vulvovaginal pain in any individual probably results from a combination of factors, all of which differ from person to person and will affect sexuality in different ways. Pain may be present from a person’s first sexual encounter or may develop after years of typical sexual functioning. While it is tempting to simplify sexual pain as either the result of physical/anatomical factors, or as a reflection of psychological difficulties, in reality they are often intertwined and inseparable. Therefore, diagnosis and treatment of vulvovaginal pain require a biopsychosocial approach.85

Vulvovaginal pain affects all phases of sexual function,86 including desire, arousal, and orgasm. Pain and the anticipatory fear of pain may interfere with the ability to tolerate touch and decrease physical and psychological receptivity to penetration and other sexual activities. It can also alter relationship dynamics and expectations, change an individual’s sense of self, and alter one’s overall ability to embrace pleasure.

Some people with vulvar pain are known to put up with great discomfort in order to continue sexual activity,87 while others may avoid sexual activity altogether. The effects on the individual and the couple will differ from relationship to relationship. A quality healthcare team can help individuals and their partner(s) find successful sexual adaptations, integrate treatment strategies, and accept any aspects of their situation that cannot be changed.

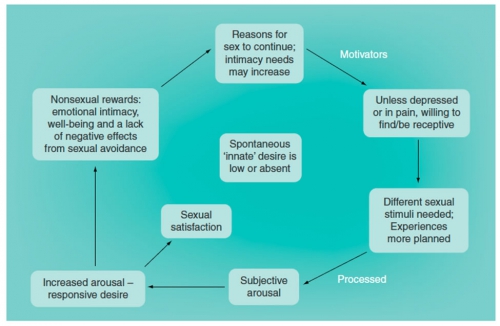

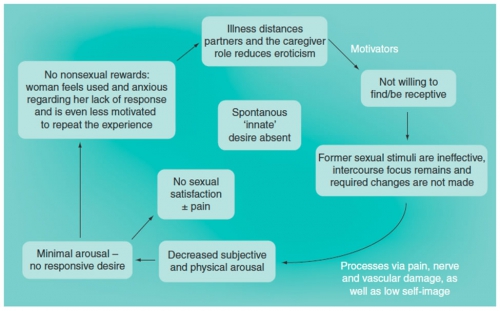

Basson’s models below comparing healthy and dysfunctional sexual adaptation in chronic illness88 also describe sexual adaptation to vulvovaginal pain.

Figure 4. Healthy adaptation of sexual response to chronic illness89

According to Basson, when there is a healthy adaptation to illness or pain, sexual desire may be absent but the person’s reasons for wanting to have sex persist. If pain is well controlled and the person is not depressed, they may remain receptive and become aroused by sexual stimulation. A variety of changes such as different positions and/or alternative stimuli, may be very helpful to facilitate positive sexual experiences. These may provide non-sexual rewards such as emotional intimacy and negate the desire to avoid sexual activity.

Unfortunately, healthy adaptation may not occur, or physical symptoms may be too great to overcome. Pain may push partners apart. Formerly arousing stimuli may no longer be effective. This may decrease arousal, desire, and/or future motivation to engage sexually.

Figure 5. Sexual dysfunction resulting from chronic illness.90

Associated Factors and Sequelae

Because the combination of sexuality with pain is physically, emotionally, and relationally complex, and because sexuality is so culturally charged, a range of sexual and other sequelae may arise for those experiencing vulvovaginal pain. These can make healthy adaptation and/or the healing process more difficult. This will require clinicians to use the wide lens biopsychosocial model to accurately assess each patient’s unique presentation and offer the best set of treatments for the individual.

Secondary physiological sequelae

When vulvovaginal pain is present, various secondary physiological sequelae may emerge which affect sexuality. There may be a great deal of ambivalence about participating in sexual activity when there is anticipation of pain. Sometimes when a person with vulvovaginal pain wants to, or believes they should be active sexually with their partner, they may decide to push through the pain.91

The body, however, may respond in a protective way by creating a secondary symptom. This could take the form of vaginismus, pelvic floor dysfunction, or other physiological symptoms that are not compatible with sexual feelings or activity. There may also be a lack of physiologic arousal including lubrication and engorgement, further increasing pain.

Psycho-emotional sequelae for the individual

Difficulty with basic sexual functioning, compounded by these secondary physiologic symptoms can lead to a variety of psycho-emotional sequelae for the individual. Overall mental health can suffer for those experiencing vulvovaginal pain, which then may cause additional sexual dysfunction. Mood and anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, and depression can be increased in women with vulvodynia.92 93 The person may believe that they are flawed and inadequate and feel shame as well as guilt. Genital pain has been shown to increase levels of anxiety, avoidance behaviors, and catastrophizing about the pain.94 95 Although general body image may not be affected, women with vulvodynia may have more anxiety about exposing their bodies during sexual activity.96 The person may consciously or unconsiously avoid sex. It is common to feel guilt and/or fear about avoiding sex or needing to stop sexual activity. Therefore they may continue sexual activity until pain is unbearable.97

Basson writes of a perpetuating cycle in which stress amplifies the pain, affecting the ability to respond sexually, thus adding to the anxiety exacerbating sexual dysfunction.98

Higher depression scores predict higher pain ratings. Attempts to provide treatment are frequently unsuccessful if anxiety and depression are not adequately addressed. Patients with untreated depression report high rates of sexual dysfunction.99 In 215 case-controlled pairs of women with and without vulvodynia, those with vulvodynia had more than 6-times the odds of mood disorders compared to those without vulvodynia.100 In a recent study, rumination about vulvodynia and the negative emotions associated with the pain was the most prominent predictor of sexual satisfaction: “…it is the psychological approach to pain rather than the intensity of the pain that most contributes to sexual satisfaction.” 101

Relationship Sequelae

Anxiety about the pain and how it is affecting sexual functioning, feelings of guilt and shame, as well as worry about inadequacy as a partner, can impact the relationship and the partner. Pain can create worry and hypervigilance. Both partners may begin to observe each other, anticipating pain. This process is called spectatoring.102 103 104 105 Spectatoring interferes with natural arousal and lubrication and may interfere with erectile function. Research has shown that when people with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners are more reliant on the success of their sexual relationship for a sense of self worth, the relationship is experienced as less satisfying.106 However, when partners are affectionate, open to adaptive coping, have fewer negative responses to sexual activity, and when both partners perceive empathic responses from the other, sexual and relationship satifaction were shown to be enhanced.107 108

If sexual pain, dyspareunia, and the process of spectatoring are sustained over time, one or both partners may begin to develop aversive behaviors toward sexual activity. Sexual aversion is defined as persistent or recurrent phobic reaction to and avoidance of sexual contact which causes personal distress. Expressions of affection are limited or absent. There is a conscious effort to avoid interactions that could lead to sexual activity. It is not unusual to see couples where no physical contact is present secondary to fear of experiencing or causing pain. There may be less eye contact and other forms of physical affection, as these may be misinterpreted as sexual invitation.109

The sexual partner may also develop reactive sexual sequelae. The partner’s loss of libido or avoidance of penetration for fear of causing further pain are common, but rarely addressed, aspects of provoked vulvodynia.110 As mentioned above, some partners may develop sexual or genital symptoms such as erectile dysfunction.111

Stress due to pain that limits sexual activity can be further heightened when it relates to family planning and desire for conception. Many patients with vulvodynia do desire pregnancy and report that pain has little effect on their decision to have a baby. Rates of infertility treatment among those with vulvodynia are similar to those of the general public.112 113

Healthcare challenges and effects on clinical relationships

The clinician’s role is to facilitate both maximum reduction of pain and healthy adaptation to short and long term sexual changes. The World Health Organization stresses the importance of sexual health care and access to quality information about sexuality and sexual health.114 The U.S. Surgeon General has called for healthcare providers to address the issue of sexual health with patients.115 Yet, while recognition of the importance of pain in sexual function is present among many healthcare providers, very few actually bring up the issue of sex or screen for sexual difficulties.116 117 118 One study of OB/GYNs in the U.S. showed that the majority (63%) do routinely ask about sexual activity, however far fewer ask about specific aspects of sexual concerns (40%) or satisfaction (28.5%).119 A large global study showed that only 9% of patients between the ages of 40 and 80 were asked about sexual issues by their physicians.120 Possible patient embarrassment, provider discomfort, time constraints, and lack of training, among others, were cited as reasons for not raising sexual issues with patients.121 122 123 124

In many cases, patients also avoid asking for help or information about sexual concerns, but expect or hope that the clinician will initiate the discussion.125 Patients often find it difficult to discuss sexual concerns with caregivers, citing a variety of perceived barriers (including their own) as well as healthcare professionals’ embarrassment, and a belief that their concerns could not be addressed because of the limitations of the healthcare setting.126

Clinicians can become overwhelmed when confronted with the complexity of the physical as well as psychosocial and relational nature of pain with sexuality. This can be difficult for many clinicians, both because of appointment time constraints and a lack of training in how to undertake this sensitive discussion. Medical and nursing schools spend very little time teaching about sexual health, sexual functioning, and taking a sexual history.127 128 129 130 Patients experiencing recurrent pain can elicit feelings of powerlessness in healthcare professionals131 for a number of reasons. The chronic nature of pain, and the strong emotions it generates, as well as the ability of genital pain to negatively impact all aspects of sexuality can be very challenging to clinicians.

Although pain may precipitate many psychological manifestations, a primary psychological cause of vulvodynia is not supported.132 133 134 When a patient presents with sexual or vulvovaginal pain, clinicians may assume a history of sexual violence or other trauma. However, while a history of trauma can be associated with vulvovaginal pain, not all patients with vulvovaginal pain have a history of sexual tauma. Literature on the subject is mixed.135 136 137 In order to accurately diagnose and treat vulvovaginal pain, it is important for the clinical provider to consider the entire spectrum and nuances of a patient’s particular experience using a biopsychosocial lens and be able and willing to engage in discussion of current sexual function and sexual history with the patient.

Treatment Approaches

Just as there are no unique treatments that apply to all patients who have symptoms of chest pain, abdominal pain, or headache there are no unique treatments that apply to all patients who have the symptoms of dyspareunia or vulvovaginal pain. Vulvovaginal pain is a symptom, not a diagnosis. Different causes of vulvovaginal pain require different treatment modalities. By its very nature, vulvovaginal pain leads to sexual sequelae, which can differ based on innumerable factors and require varying treatments and interventions. Patients benefit from a thorough multidisciplinary biopsychosocial assessment and treatment plan, potentially including medical evaluation and treatment, physical therapy evaluation and treatment, and sex therapy or other psychological evaluation and treatment.138 These are thoroughly reviewed in Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia.

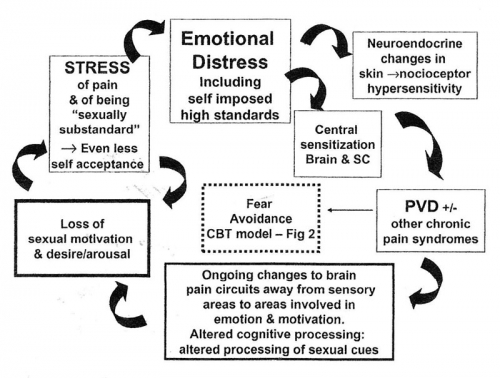

The following circular model of provoked vestibulodynia by Rosemary Basson illustrates the compounding effects of ongoing chronic pain and/or sexual dysfunction on the patient’s sense of well being. Emotional distress associated with premorbid anxiety, depression, catastrophization, harm avoidance, hyper-vigilance, low self esteem, and a tendency to perfectionism may be associated with neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system leading to central sensitization and pain amplification. Feelings of being sexually substandard compound the etiological factors and lessen sexual motivation and response. Pain-induced cognitive changes may impair processing of sexual stimuli generally and at the time of sexual activity. Motivational changes associated with chronic pain circuitry may further impair sexual motivation. Stress responses of muscles and skin add to the pathophysiology.139 A book that directly addresses chronic vulvovaginal pain and sexuality is The Pleasure Prescription: A surprising approach to healing sexual pain, Luminaire Press, 2021 by pelvic floor physical therapist Dee Hartman and sex therapist Elizabeth Wood.

Basson’s circular model of provoked vestibulodynia140

In some cases, treatment of vulvovaginal pain may be relatively straightforward and alleviating pain and/or pelvic floor dysfunction can resolve sexual problems. However, in other cases, the situation can be more complex and additional issues may interfere with resumption of sexual activity. Fear of pain, with its associated challenges, may persist, and sexual dysfunction may be ongoing, independent of vulvovaginal pain. For some patients, having a clinician legitimize and clarify sexual concerns may be therapeutic in itself. However, in many situations the clinician may need to refer the patient to a colleague for further pain management, sexual therapy, couples’ counseling, or management of anxiety or depression.

Given the complexity of sexuality, including physical, psychological, societal, and interpersonal components, a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach often makes sense and is necessary. A multidisciplinary team may include mental health providers, sex therapists, physical therapists, and practitioners of multiple medical specialties including but not limited to gynecology, dermatology, dermatopathology, urogynecology, gastroenterology, neurology, physiatry, and more. Establishing a group of sex positive, trauma-informed colleagues with expertise and interest in sexual medicine and vulvovaginal health for referral and collaboration is recommended. The Society for Sex Therapy and Research (https://sstarnet.org/) and The American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists (https://www.aasect.org/) are good resources to find trained and specialized sex therapists and counselors. The Herman Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute (https://hermanwallace.com/) and American Physical Therapy Association (https://www.apta.org/) offer certifications in pelvic or women’s health and are good resources to find physical therapists with expertise in vulvovaginal pain.

Female sexuality and vulvovaginal pain have been under-researched and, as such, many medical treatments are off-label and are based on expert opinion, range of experience, and the data that exist. There is no one clear path to treatment and some treatments work better for some patients than others. Information and reassurance, when appropriate can be given after identifying a known cause of pain such as dermatosis, sexually transmitted infection, effects of allergens and irritants, vaginitis, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, pelvic floor dysfunction, and/or interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome), among others. If no known cause can be ascertained, vulvodynia is the likely diagnosis. See section on Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia for complete info: https://vulvovaginaldisorders.org/vulvar-pain-and-vulvodynia/ Sexual function is unlikely to improve until the pain is under control. Even if one treats the cause of some types of vulvovaginal pain, for example, herpes simplex infection, pain may remain (e.g. post-herpetic neuralgia). Providing education and support about persistence of pain despite treatment of the initiating cause may be beneficial. Treatment must be individualized and finding the right treatment can be a slow process that may take some trial and error. Open dialogue, discussing patient goals, setting realistic expectations, and using shared decision making is important. General information is found below and more detailed information about treatment modalities can be found throughout this website, depending on diagnosis.

Identify and treat any recognizable causes for pain. Vulvodynia and pudendal neuralgia may be symptomatic without any physical signs of disease.

- See all steps of the Diagnostic Algorithm

- See Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia, or Annotation K for complete information on vulvodynia and pudendal neuralgia diagnosis and treatment.

- See Vaginismus/Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Implement behavioral and educational interventions

- Identify and eliminate any possible pain triggers

Stop offending irritant activities on the vulva (Annotation J: Lifestyle issues). Although soap is an unlikely culprit, every aspect of the patient’s lifestyle must be explored for possible contributing factors. Inquire about use of detergents, perfumes, deodorant sprays, wet wipes, and other feminine hygiene products, tight clothes, underwear worn to bed, sitting for long periods, bicycle or horseback riding, etc. and advise on best behaviors. See general vulvar care handout

- Diagnose and suppress any vaginitis: candida, inflammatory vaginitis, trichomonas (Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy, and cultures). Remember that bacterial vaginosis is not a significant cause of pain.

- Suppress herpes if active. (Centers for disease Control:www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/treatment.htm)

- Marsupialize recurrent/persistent Bartholin cysts (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders). We have seen provoked pain in the vestibule chronically inflamed by such cysts.

- Provide adequate local estrogen if there is atrophy. (Annotation P: GSM) Diagnose and treat lesions of dermatitis, dermatosis. (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders)

- Recognize systemic disease such as drug reaction, Sjögren, or Crohn disease, and treat vulvar manifestations. (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium)

- Consider seminal plasma allergy if history suggests. (Semen allergy: Atlas of vulvar disorders)

- Consider issues such as painful bladder syndrome (interstitial cystitis), pelvic floor dysfunction. (Annotation L: The pelvic floor)

- Refer to physiatrist or physical therapist to evaluate and treat musculoskeletal problems possibly affecting pelvic floor and pudendal nerve. (Annotation L: The pelvic floor.)

- Consult experts regarding pain in other areas, (e.g., gynecologist for endometriosis, urologist for interstitial cystitis), to make sure that all components of a regional pain syndrome are addressed.

- Always ask yourself if there is any possibility of a premalignant or malignant lesion. (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders.)

2. Educate about vulvar pain

Explain normal vulvovaginal anatomy and functionality as necessary. Use a mirror during your exam. Use handouts (to patient handouts), website referrals, and local support groups. Emphasize that pain may need to be managed, not cured. Describe the typical slow and gradual regression of pain that may occur. Discuss global impact on every aspect of sexuality, emphasizing that pain must be managed first; then work on sexual function can occur. Discuss the psychology of pain, factors that worsen pain, and the importance of taking charge. Learn about a woman’s erroneous cognitions about her pain, and work to eradicate them. Discuss fear avoidance techniques. Suggest Margaret Caudill’s How to Manage Pain Before It Manages You, 3rd edition. New York, Guilford Press, 2009 or The Pain Management Workbook by Rachel Zoffness, New Harbinger Publications, Inc. Oakland, CA, 2020. Healing Painful Sex: a woman’s guide to confronting, diagnosing, and treating sexual pain. Deborah Coady, Nancy Fish. Offer counseling for support, anxiety, depression, or relationship problems.

3. Provide information about comfort measures

Flares of pain from vulvodynia can be minimized in a number of ways (Self Help Tips for Vulvar Skin Care: http://www.nva.org). By far, the most important comfort measure is the technique of “Soak and Seal:” sitting in comfortable water (tub, sitz bath under the toilet seat, or gentle hand held shower for 5-10 minutes twice daily). A woman who is physically unable to use the tub or sitz bath may protect the bed with plastic sheeting and use sopping wet warm compresses. Pat dry gently; then seal in the moisture with a film of petrolatum or mineral oil. Some find pure coconut oil soothing and non-irritating. Cool gel packs wrapped in a soft cloth are also important to pain management. Although ice against the skin can cause frostbite, pain is significantly allayed by cold packs.

4. Set expectations

While the symptoms of persistent vulvar pain (vulvodynia) may remit entirely, it is possible that they improve but do not disappear; i.e. they are managed, not cured. This is an important concept to emphasize at the initiation of therapy. There is no crystal clear cure, no magic bullet, no one-size-fits-all approach. There is improvement with time and effort. The preceding statement is particularly difficult for a woman who has “tried everything.” However, exploration with her may reveal some gaps: poor provider-client communication and “chemistry,” inadequate trial time, underuse of all aspects of a therapy, e.g., lack of internal work with physical therapy, insufficient time with cognitive behavioral therapy, unrevealed history of sexual abuse.

5. Provide guidelines for sex

We ask women who have pain on penetration to stop vaginal intercourse until there has been some improvement in symptoms. Ongoing intercourse in the presence of pain is a negative reinforcer and can lead to secondary vaginismus. (https://vulvovaginaldisorders.org/pelvic-floor-dysfunction/ ) We encourage open communication between a woman and her partner about her pain with the effort to prevent feelings of rejection. We encourage intimacy and the pursuit of any mutually agreed upon pain-free alternatives to vaginal intercourse.

If sexual intercourse is possible with a level of comfort acceptable to the patient, we recommend use of a lubricant. Using a lubricant as a regular part of sexual activity can reduce friction, increase comfort, and relieve any perceived pressure to lubricate as an external signal of arousal. Lubricants may be water, silicone, or oil based. Care must be used in selecting a lubricant, especially if using condoms. Flavored lubricants, those promoting cooling or warming sensations, or that contain alcohol can be irritating and should be avoided.141 Latex condoms are not compatible with oil-based lubricants or vaginal medications. In women using condoms, a water-based lubricant is appropriate (e.g., an iso-osmotic, pH balanced product, e.g., Pre-Seed®). See info on lubricants. Some women find a decrease in sexual pain with use of side-lying or rear entry. See Guidelines for Sex When You Are Having Pain.

In the past, patients with vulvodynia were advised to apply topical lidocaine 4% or 5% to the vestibule up to five times a day to “calm the nerve endings;” topical lidocaine was also used prior to using dilators or other penetration. A very important case controlled study in 2010 showed that neither oral desipramine nor topical lidocaine alone or both used together, were any more effective than placebo.142 However, application of topical lidocaine ten to twenty minutes prior to attempt at intromission (then wiping it off in lieu of a lubricant) effectively numbs the skin and can reduce fear and experience of pain with penetration, allowing patients to become more trusting that penetration is possible. The patient is warned that lidocaine 5% ointment stings for about one minute after application. 4% aqueous lidocaine must be applied with a cotton ball and does not sting). This practice is discouraged by pelvic floor physical therapists who hope to enable patients to have comfortable penetration without lidocaine.

Medical Treatments

Medications used depend on diagnosis and cause of vulvovaginal pain. They can generally be grouped into oral, topical, and injectable treatment options. As mentioned above, many treatments are off-label with dose and recommended use based on limited data and expert opinion and experience. https://www.nva.org/learnpatient/medical-management/)

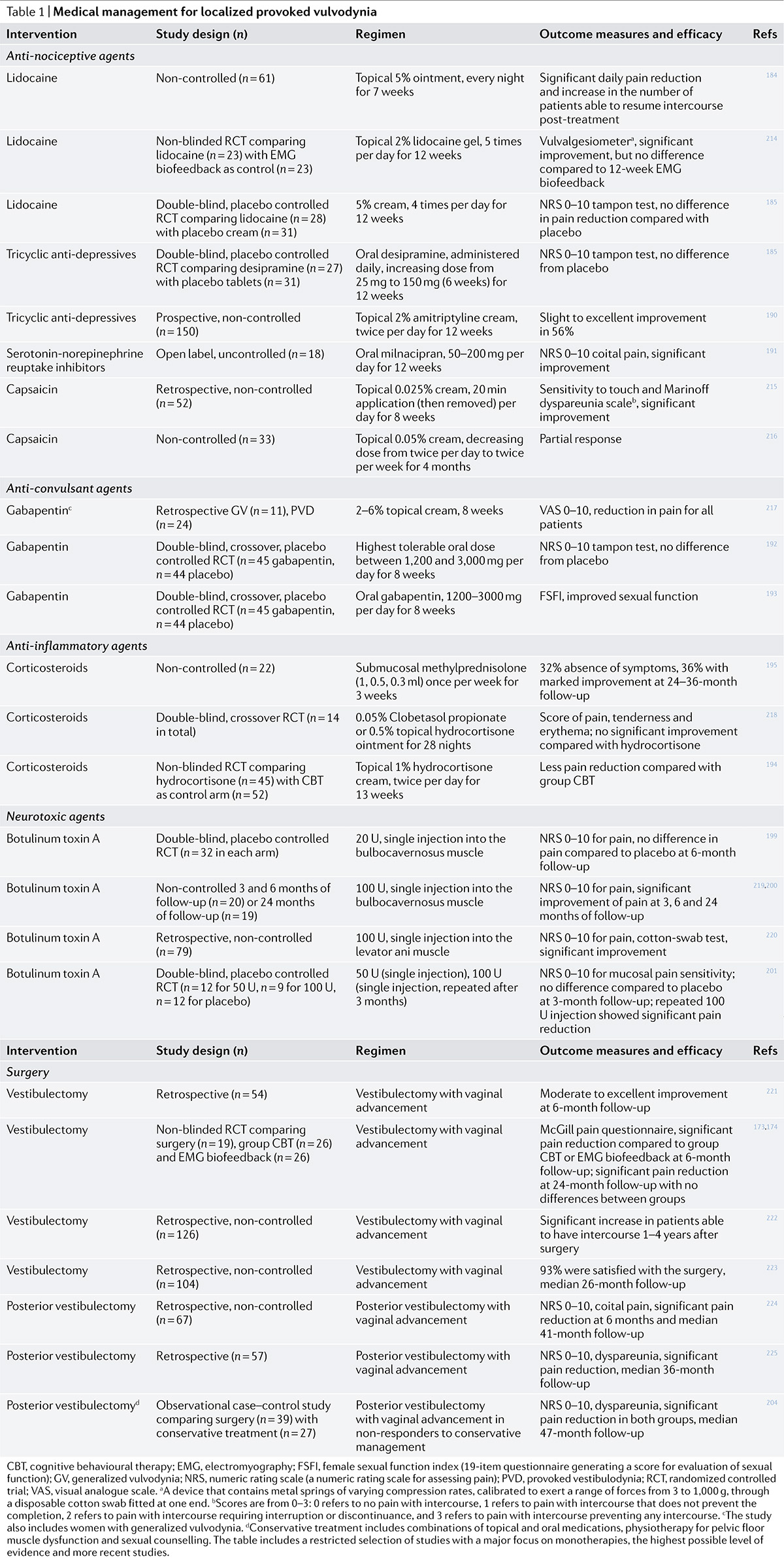

Oral Medications

Oral medications can include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals, steroids, antihistamines, and more depending on diagnosis. Several anti-seizure medications and antidepressants are commonly used in the treatment of neuropathic pain. However, the use of oral medications, in the absence of evidence-based efficacy for chronic vulvovaginal pain, has fallen off. See Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia for complete information on diagnosis and treatment trends. The following chart from Bergeron, et al, used with permission of the publishers, summarizes the most recent findings about medical management of this devastating condition.143

When antidepressants are used in the treatment of chronic pain, their pain relieving action is separate from their antidepressant action, and they are typically used at lower doses than those used to treat depression. Counseling should also include discussion of side effects. Some side effects may be barriers to use, including the possibility of sexual side effects such as decreased libido or orgasm. In some cases side effects can be used advantageously (e.g. nighttime dosing of a medication that causes sleepiness to enhance rest and/or minimize nighttime scratching).

Addressing adverse sexual side effects from SSRIs

While modern antidepressants are very effective for the treatment of depression and anxiety, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as well as other medications (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), SRI tricyclic antidepressants, SRI antihistamines, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tetracycline antibiotics such as doxycycline, and analgesics like tramadol) have been reported to reduce libido in women and men, to cause anorgasmia in women, and to increase ejaculation latency in men, as well as other unwelcome sexual side effects.144 145 Another potential complication may be persistent (“enduring”) sexual side effects that continue after the medication is stopped.146 147

Treatment options for patients who complain of sexual dysfunction while on an SSRI include the following:

- Dose reduction: Lowering the dose of the SSRI is sometimes successful, although not well studied. The antidepressant effect may diminish when the SSRI dose is decreased. This change needs to be discussed with the woman, and attempted cautiously with careful monitoring of the patient’s level of depressive symptoms.

- SSRI switch: While there are reports of some SSRIs causing less sexual dysfunction than others, there are no definitive comparison studies.

- Non-SSRI trial: Bupropion, nefazodone, and mirtazapine appear to have no effect or only a limited effect on sexual function.

- Addition of a second drug to offset the adverse effects: While the addition of bupropion 150 mg/d added to an SSRI was no more effective than placebo in a controlled study,148 a controlled study of 150 mg bupropion twice daily showed improved sexual desire.149 A systematic review discussed a third randomized study which also demonstrated improvement in desire, though not orgasm, in women treated with an SSRI and bupropion 150 mg per day compared to SSRI plus placebo.150

- Drug holidays: Drug holidays have not been well studied in patients with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. An open-label non-randomized study of weekend drug holidays found no benefit for patients taking fluoxetine and inconsistent results for patients taking sertraline and paroxetine.151

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

Physical therapy is often an integral part of treatment for vulvovaginal pain and dyspareunia. It is often unknown if pelvic floor dysfunction caused vulvovaginal pain or was created secondarily to vulvovaginal pain. Regardless, it is common for patients with sexual pain to have hypertonic pelvic floor muscles, associated myofascial trigger points, and increased tension in the abdomen, back, and hips.152

Finding a physical therapist with specialized training and interest in pelvic floor is essential when treating vulvovaginal pain and sexual function. The Herman Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute (https://hermanwallace.com/) and American Physical Therapy Association (https://www.apta.org/) offer certifications in pelvic or women’s health. Physical therapists with expertise in vulvovaginal pain can be found on these websites.

Treatment can include stretching, core stabilization, external and internal tissue release and manual therapy, biofeedback, electrical stimulation techniques, relaxation techniques and dilator therapy. See

Annotation L: The pelvic floor, Vaginismus/Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia for more.

Dilators can be used to maintain patency, decrease anxiety, lessen trigger points, and increase self-efficacy for attempting and completing vaginal penetration, however, there is no standardized treatment protocol for use of vaginal dilators153 While medical and mental health clinicians can provide instruction in the use of dilators, physical therapists may be especially well suited to guide a home program of dilator therapy. For more information on dilator use, please see Vaginismus/Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Annotation L: The pelvic floor).

Physical therapists can play a unique role on the patient’s multidisciplinary team. They often see patients more regularly than the medical provider and can gain insight from physical exams not independently available to the mental health clinician. Collaboration between these providers can greatly enhance patient outcomes.

Psychosocial Counseling and Therapy

All patients with vulvovaginal pain require and deserve at least some level of psychosocial intervention as part of their plan of care because vulvar pain can affect so many parts of an individual’s emotional, psychological, relational, sexual, and general physical functioning. Because medical providers are often the first and possibly the only provider a patient may see, some basic psychosocial interventions can be extremely useful in this setting. The intensity and complexity of these interventions can be increased as needed.

The PLISSIT model is the hallmark guide to stepwise interventions moving from brief focused discussion all the way to in-depth psychosocial assessment and treatment if needed.154 155

In this model diagrammed below, the provider may initiate a discussion about sexual concerns during a healthcare visit, both asking for and giving “permission” to talk about sexual concerns, thereby indicating to the patient that sexual health is an important and legitimate topic in the medical setting. In some instances the discussion may stop there, however if the patient chooses to disclose a sexual health concern, the provider can offer “limited information” to address the issue. In the case of sexual pain, this may include education about causes and prevalence of vulvovaginal pain, genital anatomy, and/or possible common effects of vulvar pain on sexual functioning and relationships. Depending on the provider’s comfort level and knowledge about sexual health, they may move on to offer “specific suggestions” tailored to the needs and concerns of that particular patient. The “specific suggestions” may address topics such as the use of lubricants and/or dilators, relaxation techniques, strategies for communication with a partner, and suggestions of alternative sexual positions, among others. If this is outside of the provider’s comfort level or scope of expertise, this would be an appropriate time to refer to a healthcare provider more knowledgeable on this topic or a professional with some training in psychosexual counseling and healthcare. The last step in the PLISSIT model is “intensive therapy,” often facilitated by referral to a sex therapist or other mental health professional who could give more extensive and in-depth guidance and counseling to the individual and partners. “Intensive therapy” might also incorporate the first three parts of the PLISSIT model and additionally offer guidance to help create more adaptive responses to vulvar pain. It can help the patient explore and address personal, emotional and relationship sequelae that may have developed in response to vulvovaginal conditions, their treatments, and to process past or current experiences that may be exacerbating sexual difficulties. This is also the place to address concomitant factors, such as depression and anxiety, relationship difficulties, trauma and/or other issues that are beyond the scope of the medical provider.

Referral to a psychotherapist or sex therapist for more intensive treatment is sometimes a difficult step to take because mental health care often carries a stigma. The patient, as well as the healthcare clinician, may wrongly assume that this implies that the pain is somehow not real or is purely psychological. Emotional responses to vulvovaginal pain and the possibility of far reaching sequelae for the individual and their partner(s) need to be validated by the clinician. Clarification about the reason for the referral and the ways that more intensive therapy can help would be an important part of the discussion with the patient.

PLISSIT MODEL – Adapted by Terri Couwenhoven MS, AASECT Certified Sex Educator

| Most

people need

Fewest people need |

Component | Student/Client Needs | Helper Role Characteristics |

| Permission | Most people simply need permission to talk and learn about sexuality and explore their own attitudes and responses. | Helper should be able to provide “permission-giving” statements to students creating an atmosphere of comfort and acceptance. Permission is the most important level of the model.

Attitudes, knowledge and skills required: ❑ acceptance of sexuality as positive force ❑ ability to discuss sexuality w/ease & comfort ❑ relate to & accept the person being counseled ❑ address needs at their level ❑ compassion, warmth, and trustworthiness |

|

| Limited

Information |

In addition to permission, some people need limited information to begin to explore their own sexuality and/or explore with another person. | Helper should have basic information about sexuality. At this level, myths and misconceptions should be clarified and corrected. Information provided is specific to the question or concern being expressed.

Attitudes, knowledge and skills required: ❑ above characteristics ❑ accurate information about sexuality issues. |

|

| Specific

Suggestion |

For some people, the addition of a specific suggestion can be useful. For example, suggesting a relaxation exercise or an activity for learning about ones own sexual response | Options for managing sexuality related concerns/difficulties are developed at this level. Counseling skills are required and a designated place is helpful.

Attitudes, knowledge and skills required: ❑ more advance counseling and education ❑ increase knowledge on sexuality and disability ❑ problem solving abilities ❑ behavior modification techniques |

|

| Intensive

Therapy |

In addition to above needs, a smaller number of people will need intensive therapy to help them address sexuality issues. | Intensive therapy takes a great deal more time, and is provided by a trained counselor. For sexual issues, intensive therapy often involves work that addresses all aspects of a person’s experience i.e. emotional, physical, interpersonal, spiritual, intellectual. |

Psychotherapy and/or Sex Therapy: A medical practitioner wanting to refer a patient for more in-depth treatment of a sexual concern may not be clear when and if they should refer to a sex therapist or general psychotherapy practitioner. This will depend not only on the needs of a particular patient, but also on local availability of sex therapy and psychotherapy as well as the patient’s financial access to specialty care.

A general psychotherapist can be highly competent to treat sexual concerns, depending on their experience and expertise. They may, however, approach sexual issues differently than a sex therapist, addressing a variety of complex interactive and intersectional psychosocial problems of which the sexual concerns are a part. Psychotherapy may help the individual and/or partner(s) explore beliefs about sex, address shame, self esteem, relationship difficulties, and other issues that may relate to the sexual concerns. If the patient has experienced physical or sexual abuse or trauma, has serious depression or anxiety causing major dysfunction, has suffered significant losses, is/has been suicidal, or has experienced other major stressors or mental health problems causing difficulty much beyond sexual functioning, a more in-depth therapy would likely be an important referral consideration. If the psychotherapist is not comfortable or does not have enough expertise to provide treatment for particular sexual health issues, they may refer the patient for consultation and/or further treatment to a sex therapist. Similarly, if a sex therapist finds that the patient needs to address more complex issues outside of their expertise or comfort level, they may refer to another more appropriate psychotherapist.

A sex therapist is a mental health clinician, licensed in their professional field (psychiatry, psychology, social work, marriage and family counseling, etc.) who has obtained additional training in sexual health and sex therapy. They may use various talk therapy treatment modalities and interventions based on the needs of the particular patient including psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness techniques, relationship/couples therapy, and trauma work, among others. Certified sex therapists may be located through the websites of the American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors, and Therapists: www.aasect.org and the Society for Sex Therapy and Research https://sstarnet.org.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Mindfulness-based Therapy 156 157 are psychotherapeutic approaches used for a wide variety of emotional, cognitive, and relationship difficulties by psychotherapists in many specialties, and have been the most extensively researched psychosocial interventions to address vulvovaginal pain. These interventions, adapted for sex therapy, have shown clear benefits for both pain and sexual dysfunction158 and are even increasingly being used as first line treatments for sexual pain both because of the growing evidence of their efficacy and to avoid potential negative side effects from medical treatments.159 These approaches help the patient and partner(s) evaluate and modify expectations, better understand their own sexuality, communicate more clearly and ultimately cope more successfully. At times this work may even help lessen the pain by changing how the patient feels and thinks about the pain and sexuality.

CBT was originally developed in the 1960’s by Dr. Aaron Beck for treatment of a wide range of mental health concerns. It is a widely used psychotherapy technique and can address maladaptive thoughts, cognitions and behaviors that cause distress. It has been adapted for use with sexual pain and helps patients change their thought patterns related to or caused by the pain, and has been associated with improved sexual outcomes.160 Mindfulness based therapy for sexual pain grew out of a widely used therapeutic technique called Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) originally created by Jon Kabat-Zinn in 1979 to address stress and was adapted for use with many medical conditions particularly with chronic pain. Mindfulness-based therapy helps the patient and their partner(s) observe actual body sensations without adding judgment, expectations, catastrophizing and other negative thoughts that can be attached to the sensations and exacerbate pain. Both techniques can be adapted for use with couples and individuals and have been found to have similar rates of effectiveness in helping patients cope with pain and decrease sexual distress.161 162 163 164

Clinical hypnosis, although less researched for vulvovaginal and sexual pain in particular, has proven to be a very useful treatment for many types of pain.165 166

Couples Therapy: Sexuality is often very difficult to discuss openly, even among intimate partners. Misunderstandings, misinterpretation of intentions and expectations, anger, shame, distrust and other outcomes can develop and harm a relationship. Including partner(s) in couples therapy, using any of these psychotherapeutic approaches, can be very helpful by opening discussion and improving communication between partners about the effects of sexual pain on each person and on the dynamics of the relationship.167

Both the sensate focus technique and the “good enough sex” model described below are common sex therapy interventions, among many others, that may be helpful in addressing sexual pain and can be combined with the clinical approaches described above.

Sensate focus, a technique used in partnered sex therapy which can also be adapted for use with individuals, was originally created by Masters and Johnson and reintroduced by Linda Weiner and Constance Avery-Clark.168 169 170 It is a form of mindful non-gential touch that helps the patient and partner(s) focus on their own sensual experience as they take turns giving and receiving non-genital touch. In the context of pain, this can guide partners to focus on pleasurable touch and to avoid pushing through pain, giving permission to explore intimacy without penetration.

The “Good enough sex” model is another widely used sex therapy concept developed by Barry McCarthy and Michael Metz.171 It guides partners to focus mainly on intimacy and to accept that the quality of sex changes from one sexual encounter to another depending on many variables. This allows the patient to accept and enjoy sex without imposing unrealistic performance expectations and goals on their sexual activities. This framework can help patients and their partner(s) recognize that one sexual encounter that feels “unsuccessful” or disappointing does not mean that the relationship or sex life is “doomed.” With this approach to sex, activities that cause pain do not have to and likely should not be part of the sexual repertoire, and alternative activities can be explored thereby greatly decreasing sexual and relationship distress.

Group Therapy: An alternative to individual and couple’s therapy for sexual pain, group therapy using CBT and/or psychoeducation may work best for some patients. Group therapy in the context of sexual pain is often curriculum based, time limited and cost effective. Sharing experiences with other women or couples can be empowering and validating and offer hope.172 173

Trauma-Informed Approach to Care

The clinical community is developing a greater understanding of the prevalence of trauma and the ways that trauma impacts health at every level. It is incumbent upon every provider, especially those working in sexual health to understand and practice trauma-informed care. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a trauma-informed approach is one that “realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths to recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff and others involved in the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.174

A trauma-informed approach calls for a paradigm shift in approaching people – from an attitude of “what is wrong with you?” to the curiosity of “what happened to you?” Understanding the ubiquity of trauma requires that this approach be employed universally, for all patients/clients (as well as co-workers and colleagues), rather than only in instances where a history of trauma is known. While providing a comprehensive history is helpful to allow the provider to give the best possible care, patients/clients do not owe disclosure to providers. A trauma-informed approach should be the standard of care for all.

While literature is mixed, some studies have shown an association between vulvovaginal pain and history of trauma. Some research indicates that women who developed vulvodynia as adults were significantly more likely to report childhood abuse, (physical or sexual) than age matched controls and that adverse life events such as destructive relationships, parental divorce, or adverse childbirth experiences are more frequent in women with vulvodynia than in women without.175 176

In every interaction, clinicians must seek to avoid re-traumatization, recognizing that the process of seeking care for vulvovaginal pain has many potential opportunities to be activating or “triggering” for patients/clients. These include but are not limited to power dynamics inherent in the provider-patient relationship, potential discomfort with being undressed, multiple elements of the pelvic examination, and discussing sexual history and practices. Patients as well as providers may believe that components of care are medically necessary, however this can limit a patient’s ability or willingness to freely decline elements of care. In addition to being prepared to help the patient/client manage a range of responses, a focus on shared decision making, and a true informed consent process including the right to informed declination is key.

_______________________________________________________________

Behavioral and Educational Interventions

In all cases, patients can benefit from education on basic genital anatomy as well as vulvar care and hygiene practices. Avoiding vulvar irritants including fragrances, soaps, sprays, wipes, douches, and any topical creams and ointments used to try and reduce pain or “stay fresh” and encouraging cleansing with water only or a gentle soap, can help avoid dermatitis and reduce pain and discomfort.

Using a lubricant as a regular part of sexual activity can reduce friction, increase comfort, and relieve any perceived pressure to lubricate as an external signal of arousal. Lubricants may be water, silicone, or oil based. Care must be used in selecting a lubricant, especially if using condoms. Flavored lubricants, those promoting cooling or warming sensations, or that contain alcohol can be irritating and should be avoided.177 See lubricants and moisturizers table. For patients experiencing “dryness,” such as those with genitourinary syndrome of menopause, treatment with topical estrogen may resolve pain and an over the counter vaginal moisturizer used several times per week regardless of sexual activity can be beneficial.

Further guidance for behavioral modification can be found in the patient handouts “General Vulvar Care” and “Guidelines for sex when you are having discomfort or pain:”

General vulvar care patient handout

Guidelines for sex when you are having discomfort or pain handout

The section below has not yet been updated because we are seeking to coordinate the findings in Annotation K/Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia with this section. Please bear with us!

Multi-disciplinary treatment approaches to sexual pain and dysfunction

1.) Identify and treat any known cause of vulvovaginal pain.