Annotation I: Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationAny part of the vulva can be symptomatic with irritation, itching, stinging, burning, or pain. There may be tenderness from a known cause such as atrophy, lichen planus or other dermatosis, infection with Candida albicans, neoplasm, post-herpetic neuralgia, chronic contact with an irritant, or other myriad sources. There may also be discomfort from an unknown cause, i.e. there may be no identifiable lesion, nothing to see at all on inspection.

Discomfort of unknown origin may be generalized or localized. It may be provoked by sexual activity or not; it may be provoked by non-sexual activity such as the touch of clothing, or it may be “unprovoked,” present spontaneously, not dependent on physical touch at all. There may also be a mixed presentation of discomfort, both generalized and localized, both provoked and unprovoked (spontaneous), both from a known or unknown cause. (Annotation K: Provoked or unprovoked vulvodynia).

In order to help your patient, you must locate her symptoms precisely, with close attention to whether the tender areas are associated with physical findings or not. You must map systematically to identify each symptom in its exact location and to discern patterns that will help with diagnosis. It is important to remember that women may be unaware of tender foci. That is, their sensations may appear to be more generalized to them, until you ask, in the setting of the exam room, about specific foci. Discussion is not enough. Pain and symptom mapping through targeted touch is essential for diagnosis and can be quickly performed once it is part of your systematic approach.

Often women do not have the vocabulary to describe the location of their problem accurately. They may use the term “inside” or “vaginal” to refer to the inner labia, the vestibule, or the vagina. Sometimes, the clinician can help the patient: “Is your pain between the inner lips, around the vaginal opening? Is your pain deep inside the vagina?” Pain, especially neuropathic pain, can be difficult to describe and localize. Verbal description is never enough for accurate diagnosis. Ask the patient to show you with one finger specifically where her discomfort is. Always ask for permission to examine her and alert her to each new area of touch.

After you know the area(s) that cause her discomfort, begin by telling the patient that you are going to check to find out about the extent of discomfort in any painful areas. To establish a baseline from a pain-free area, start with the right inner thigh (which is not inervated by the pudendal nerve). Touch the inner thigh in a few places with a plain Q-tip, using light touch and ask if there is tenderness anywhere. “This is a zero for pain, right?” If touch on the thigh is painful, obtain quantification of the amount of pain or other symptoms, with 10 the worst pain, itching, burning and so forth. Usually, both the question and touch test are zero on the inner thighs. The Q-tip is used because it is more precise than the practitioner’s finger and the touch is less intimate from the patient’s perspective.

If touch on the thigh is painful, you can use any other body part such as the knee, foot, or hand as a baseline reference site. It is necessary to discriminate between true pain in the thigh “Does that really hurt compared with this touch on your hand,” and fear of, or anticipation of pain, “or are you afraid that it will hurt?” True pain in the thigh may suggest a complex pain syndrome. (Annotation K; Vulvar pain and provoked or unprovoked vulvodynia). Anticipation of pain may represent anxiety associated with the examination, bad experiences with past examinations, or more complex psychology. (Annotation D, Patient tolerance of genital exam).

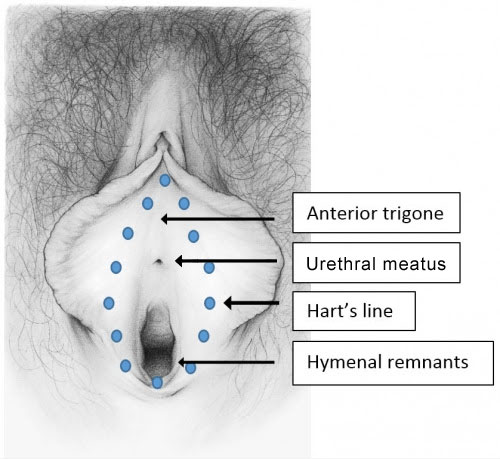

Now, begin to map; touch over the mons: is that a zero? If yes, say that it is good. No? Ask her to give a score. Then, in a similar fashion, touch down the labiocrural folds, over the prepuce, over the labia majora bilaterally, anterior to posterior, in the interlabial sulci, then the labia minora, anterior to posterior and medially to Hart’s line, over the perineum, around the anus.

Make mental or written notes of symptomatic area location and quantification of the symptom from 0-10.

If confusion arises as the exam progresses, go back to the thigh (or other body part you used as an area of zero pain). Touch the thigh, reminding patient that this is a zero. Touch the area in question again, asking if this is more than a zero and what number she would give. Be careful not to give her the answer (“This is a 10, isn’t it?”)

It is possible to have tenderness to touch with the Q-tip from 1-10 in a patient with no spontaneous pain. It is possible to have zero tenderness to touch with the Q-tip but spontaneous pain from 1-10. Both spontaneous pain and tenderness may occur together.

Documentation of pain mapping sites and quantification of the pain from 0-10 will give you an idea of the location and the severity of the pain (scores over five are considered moderate to severe pain) and will allow you to compare pain scores from visit to visit to evaluate progress.

Vulvar pain can be localized anywhere, but commonly, the most acute pain is found in the vestibule.

Boundaries of the vestibule

The bilateral elliptical space of the vulvar vestibule is a narrow epithelial strip surrounding the vaginal orifice. Just inside the labia minora, the vestibule extends from the clitoral frenulum to the labial fourchette. It has lateral boundaries of Hart’s line, delineating the change from keratinized epithelium laterally to non-keratinized epithelium medially. The medial boundary of the vestibule is the hymenal ring.

The vulvar vestibule, derived from endoderm, is subject to all the epithelial diseases of mucosa, as well as to allergy, inflammation from sexual activity, mechanical irritation, or elimination. Nevertheless, it is an area unfamiliar to clinicians, who fail to give it adequate attention in their quest to place the speculum for Pap smear. It is unknown to women as well.

The vestibule started to receive attention in 1987 with Friedrich’s criteria1 for the diagnosis of what was then called Vulvar Vestibulitis Syndrome:

- severe pain on vestibular touch or attempted vaginal entry

- tenderness to pressure localized within the vulvar vestibule

- physical findings confined to vestibular erythema of various degrees (Annotation K: Vulvar pain and provoked and unprovoked vulvodynia).

The definition of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, now called provoked or spontaneous (unprovoked) vulvodynia, has changed over the years as clinicians and researchers have tried to understand it. (Annotation K: Vulvar pain and provoked and unprovoked vulvodynia).

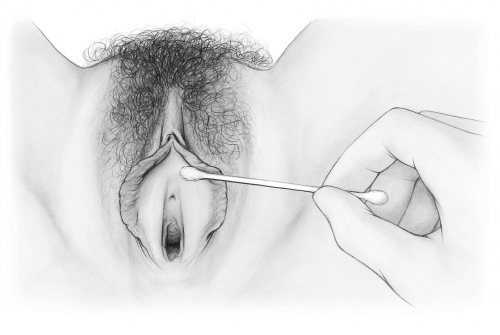

Performing the Q-tip test

The Q-tip test evolved to reveal whether or not tenderness to touch is present in the vestibule, if so, specifically where and to what degree. Touching with a Q-tip also gives information about itching, soreness, and other symptoms. After gently spreading the labia minora, one takes a Q-tip and touches around the circumference of the “vestibular clock” from 12, just under the clitoral frenulum through all the numbers to 11 o’clock. Quantify any tenderness or symptomatology from 1-10. Look for any abnormality of the epithelium and note this along with any painful or symptomatic areas.

Interpreting a positive Q-tip test

Pain on touch or pressure in the vestibule with no identifiable cause, including normal pH and microscopy and serial negative yeast cultures, allows the diagnosis of provoked localized vulvodynia (vulvar vestibulitis, vestibulodynia).While the Q-tip test has become synonymous with this diagnosis, positive findings have a variety of other interpretations.

A positive Q-tip test can mean that:

- There is pathology in the epithelium of the vestibule (vulvitis, dermatosis, contact dermatitis, atrophy, Candida, herpes). (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders).

- There is pathology (such as Candida or desquamative inflammatory vaginitis) in the vagina affecting the vestibule. (Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, microscopy, and cultures).

- C- fibers in the vestibule (nociceptors) have fired repeatedly in response to inflammatory stimuli (a phenomenon that is not well understood) leading to central sensitization in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. As a result, A fibers (mechanoreceptors) develop heightened response and there is neuropathic pain with touch. (Annotation K: Vulvar pain and provoked and unprovoked vulvodynia).

- Pain is being referred to the vestibule from other areas, e.g., the bladder in interstitial cystitis, the sacro-iliac joints (The bladder or, at this point, Annotation B: The patient’s history/Associated systems/Urinary)

- More than one of the above conditions exists, for example, there is a triggering condition such as lichen planus in a woman with marked atrophy, as well as pain from another condition such as a torn labrum in the labrum of the acetabulum. She has three conditions to treat.

You now have a map of any painful or symptomatic areas over the vulva and in the vestibule and hymenal ring. With your evaluation of the pelvic floor, you will learn about mapping the pelvic floor muscles to find any vaginal or pelvic floor muscle hypertonicity (tense and tight muscles), trigger points, and/or tenderness. (Annotation L: The pelvic floor). You will combine your map with the patient’s history, the remainder of the physical exam findings, pH and microscopy and any other testing as you continue through the algorithm towards a diagnosis.