Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationFor details on embryology and anatomic structure of the vagina, please see Annotation N. For the reader’s convenience, histology and physiology are repeated here.

Histology

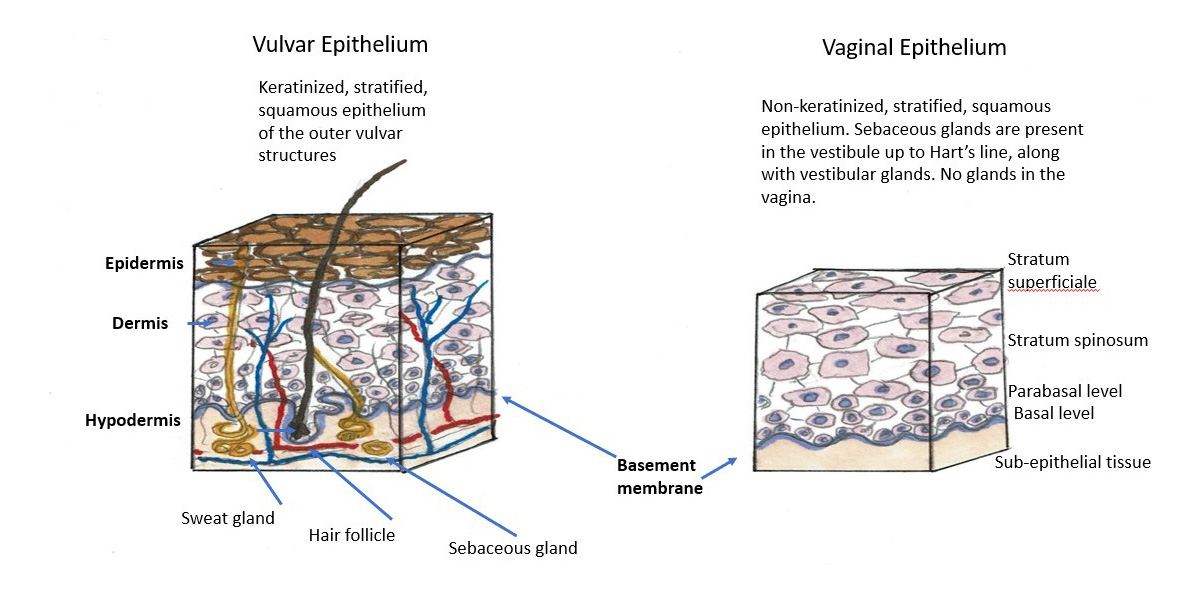

The vagina is composed of four layers: (1) inner layer of non-keratinized squamous epithelium containing no glands; (2) the lamina propria, rich in elastic fibers; (3) the muscularis layer of smooth muscle with inner circular surrounded by outer longitudinal layers and (4) the adventitial layer, which merges with the adventitial layers of the bladder and the rectum. The entire vaginal wall thickness measures 2-3 mm in a reproductive age woman but is usually thinner when estrogen levels are lower.

The epithelial layer is composed of a lower basal layer, several layers of parabasal cells and multiple layers of intermediate and superficial squamous cells that progressively accumulate glycogen. Transverse epithelial folds dip into the third layer of muscularis and contribute to the elasticity of the vaginal walls, allowing intercourse and childbirth.

Physiology

The vagina, like the uterus and the bladder, is estrogen sensitive. The estrogen acts on receptors in the vagina to maintain the collagen content of the epithelium. Estradiol maintains acid mucopolysaccharides and hyaluronic acid, keeping the epithelial surfaces moist and well glycogenated and optimizing genital blood flow.

The surface cells of the vaginal epithelium are cast off into the vaginal canal. This desquamation goes on constantly and the epithelium is replenished by mitotic division of cells in the basal layer. Using the glycogen from epithelial cell breakdown and glucose from transudation as energy sources, bacteria of the Lactobacillus genus thrive. The bacterial breakdown of glycogen and glucose into lactic acid serves to acidify the vagina.

The vagina contains no glands and is moisturized by transudation and mucus secreted from the cervix and the paraurethral, vestibular, and Bartholin’s glands, all in close proximity. (The vaginal pH and the process of using it and microscopy in diagnosis are discussed under Annotation P, Vaginal Secretions, pH, microscopy, and other testing.)

Estradiol concentration fluctuates from 40 to 60 pg/mL in the early follicular phase, peaks at 200 to 600 pg/mL during ovulation, and then falls back to 100 pg/mL during the early luteal phase. Estradiol again gradually rises to peak at 200 pg/mL during the mid-luteal phase before falling to 30 to 50 pg/mL at the onset of the menses.1 These cyclic cellular changes are not grossly evident on speculum examination, although they are reflected in vaginal smear. The vaginal maturation index (VMI) is typically used by cytologists to quantify these cytologic vaginal epithelial changes.2

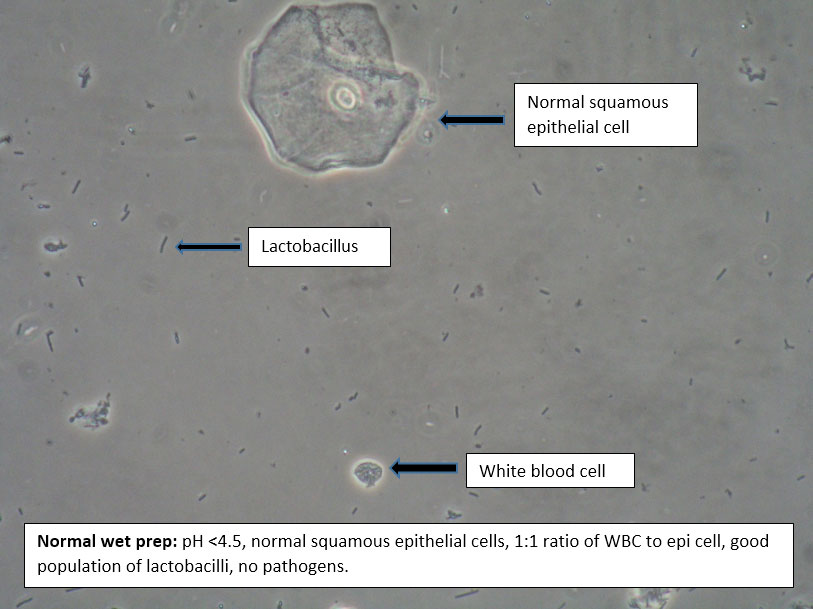

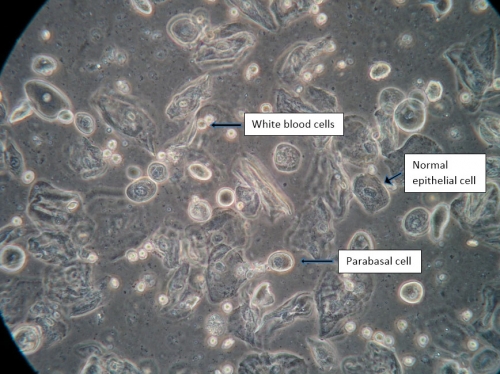

Clinically, the wet mount gives this information about cyclical cellular changes, making it essential to the evaluation of vulvovaginal complaints. ( pH and microscopy illustration ). The maturation index, determined from cytologic examination of a wet preparation of surface cells from the lower one third of the vagina, can be used to quantify the proportions of cell types of the vaginal epithelium. The maturation index is the proportion of parabasal, intermediate, and superficial cells in each 100 cells counted on a smear.3 In premenopausal women with adequate estrogen levels, intermediate and superficial cells predominate. When output of estrogen peaks immediately prior to ovulation, superficial cells predominate on the vaginal smear. Following ovulation, intermediate cells predominate. Late in the luteal phase, progesterone-induced cytolysis is evident and the cells break apart. The maturation index for premenopausal women is typically 40 to 70 intermediate cells, 30 to 60 superficial cells, and 0 parabasal cells.

As women pass through perimenopause to menopause, vaginal epithelial cells undergo less maturation and an increase in immature parabasal cells and a decrease in superficial cells are observed. Women in early menopause typically have a maturation index of 65 parabasal cells, 30 intermediate cells and 5 superficial cells. As women age and estrogen levels decline, parabasal cells will continue to increase, and the maturation index may eventually consist entirely of parabasal cells.

Parabasal cells are also a hallmark of inflammation and are seen with severe Candidal infections as well as other inflammatory vaginal conditions such as vaginal lichen planus and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

The vaginal microbiome

Introduction

Our understanding of how to treat and prevent diseases is being transformed by burgeoning knowledge of the human microbiome, the ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting every part of our bodies.4 A prime mover of this powerful advance in knowledge was the 2008 launch of The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) by the National Institutes of Health, a global endeavor involving multiple research groups and a cohort of 300 individuals. The researchers aimed to characterize the microbiomes of 18 bodily habitats of women (genital sites: vaginal introitus, midvagina, and posterior fornix) and 15 bodily habitats of men, all healthy participants. The HMP studies showed, with both culture and molecular biology, that even healthy women reveal remarkable variations in the microbes inhabiting the gut, skin, and vagina, with much diversity unexplained.5 One study showed that the number of cultured human-associated bacterial species increased from 2,776 in 2018, to 3,253 in 2020.6

In the vaginal microbiome (VMB), a total of 581 bacterial species belonging to 10 phyla have been found so far, using culture and/or molecular based techniques. Of these 10 phyla, Firmicutes, (the phylum encompassing all lactobacillus species), predominates with 227 bacterial species (39.1%), followed by Proteobacteria with 150 bacterial species ( 27.8%), Actinobacteris with 101 bacterial species (17.4%), and Bacteroidetes with 74 bacterial species (12.7%).7 8 In addition to bacterial residents, vaginal fungal communities (mycobiome) and viral populations (virome) are emerging as important contributors to the health or disease of the reproductive tract.

Recurrent vulvovaginal infections (RVVI) become epidemiological and clinical issues with social and psychological consequences.9 The biochemical and inflammatory properties of the vaginal environment may not only determine genital symptoms but may also impact conception, the ability to carry a fetus to term, the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and the risk for gynecological malignancies.10 These adverse effects of RVVI on the reproductive health and well-being of women have resulted in a major public health concern all over the globe.11

What is the “normal” vaginal microbiome?

The definition of what constitutes a “normal” vaginal microbiome continues to be a work in progress, aided by new sequencing technologies and bioinformatic tools.12 13 The dominant conclusion is that there is not just one normal VMB.14 15

Indigenous microbial communities (which both change and remain stable over a lifetime, in fluctuating equilibrium), are believed to constitute the first line of defense against infection by competitively excluding invasive non-indigenous organisms that cause diseases.16 As if in mutualistic agreement, the host provides nourishment for the resident microbiota which, in turn, protect the host. Understanding the fine-tuned interaction between the VMB and host behavior and physiology and how different microbiota may coordinate to influence health or disease is essential to moving forward on diagnosis and treatment of women who suffer from vaginal disorders.

Lactobacilli, (long recognized generally as the “good vaginal bacteria” by clinicians), do the job of maintaining the normally acidic vaginal pH by producing hydrogen peroxide and, more importantly, lactic acid as well as bacteriostatic and bactericidal compounds that restrict the growth of pathogens.

The following photo shows lactobacilli as seen under a phase-contrast microscope in the setting of a vaginal pH of 4.0, long understood as representing “normal” vaginal status in reproductive age women who are not lactating or otherwise in a low estrogen state.

Lactobacilli have long been understood to be essential constituents of healthy human vaginas, competing for nutrients and “vaginal real estate” and limiting the colonization of potentially pathogenic microorganisms. G Lactobacillus dominance in the VMB and a low vaginal pH are unique to humans when compared to other mammals, with low levels of Lactobacillus and consequent elevated pH considered one of the hallmarks of vaginal dysbioses such as bacterial vaginosis (BV).17 Research into the VMB has shown, however, that there are many Lactobacillus species and they maintain vaginal homeostasis in different ways in different populations.

In a seminal 2011 study building on the work of Zhou et al,18 Jacques Ravel et al, while hoping to identify a single human VMB, found that in a cohort of healthy, asymptomatic, reproductive-aged US women across four ethnic groups (Black, White, Hispanic and Asian), there were five distinct VMB “community state types” (CSTs).19 These CSTs contained different proportions of mostly the same phylotypes of bacteria and were dominated in number by Lactobacillus species in 4 of the 5 groups.

Ravel’s study demonstrated that while Lactobacilli are the most abundant of all taxa in CST-I, CST-II, CST-III and CST-V, different species of Lactobacillus dominate in these groups: (CST-I L. crispatus, CST-II L. gasseri, CST-III L. iners and CST-V L. jensenii). In contrast, CST-IV was characterized by a low abundance of Lactobacilli with a polymicrobial mixture of anaerobic bacteria: Gardnerella, Atopobium, Mobiluncus, Prevotella and other taxa in the order Clostridiales. Furthermore, there was a correlation between which type of Lactobacillus (or other bacteria) predominated and vaginal pH, the highest pH values being seen in women whose vaginas contained the higher diversity: bacterial community CST-IV.

Prevalence of community state types (CST) differed in the four ethnic groups in Ravel’s study, correlating with differences in normal pH values for each of these groups from 4.2 to 5.0: White (ph 4.2 +/- 0.30), Asian (pH 4.4 +/- 0.59), Black (pH 4.7 +/- 1.04), Hispanic (pH 5.0 +/- 0.74), calling into question the long-held belief that “normal” pH for women of reproductive age is 3.5-4.5.

- CST-I: L. crispatus dominant, pH 4.0-4.4

- CST-II: L. gasseri dominant, pH 4.4-5.0

- CST-III: L. iners dominant, pH 4.2-4.4

- CST-IV: non-lactobacillus species dominant, pH 5.3 +/- 0.6

- CST-V: L. jensenii dominant, pH 4.7-5.0

The researchers concluded that there are likely multiple normal vaginal microbiomes and probably dozens of factors that contribute to these varying microbiota, including genetically determined differences between hosts, differences in innate and adaptive immune systems, the compositions and quantity of vaginal secretions, ligands on epithelial cell surfaces, personal hygiene, methods of birth control and sexual behaviors.20

Ethnic groups and pH values21 (This diagram used with permission of Dr Jacques Ravel and not utilized in the referenced article.)

In Ravel’s study, bacteria were also isolated to identify those correlated with high or low Nugent scores, in hopes of better understanding the development of BV. In research settings, the Nugent test via Gram-stain scoring is still considered the gold standard for establishing a diagnosis of BV, despite there being other ways to diagnose BV. Taxa correlated with low Nugent scores included Lactobacillus phylotypes found in CST-I, II, III and V. Both Nugent scores and pH levels increased as the proportion of non-Lactobacillus species increased, but in some cases, elevated pH and Nugent scores were seen where high levels of Lactobacillus species were also seen.22

Nugent score table for gram stained vaginal smears for detecting bacterial vaginosis23

CSTs I, III, and IV in subsequent studies have been found to be the most prevalent “vagitypes” across the globe, with perhaps 90% of reproductive age women representing one of these groups with L. crispatus, L. iners and G. vaginalis being amongst the most prevalent bacterial species in populations of women from North America, South America, Europe, Asia and Africa.24 A 2012 longitudinal study of 32 healthy, premenopausal subjects by Gajer et al furthered what Ravel previously demonstrated (with the exception of CST-V not being represented, likely due to the small sample size of the study)25 but this time, CST IV was seen to divide into two subgroups, CST IV-A and CST IV-B. Both subtypes lacked significant numbers of Lactobacillus sp. but differed in composition: CST IV-A contained small numbers of either L. crispatus, L. iners or other Lactobacillus species, along with low numbers of mixed anaerobic species such as Anaerococcus, Corynebacterium, Finegoldia, or Streptococcus, while communities in CST IV-B contained higher proportions of the genus Atopobium, in addition to Prevotella, Parvimonas, Sneathia, Gardnerella, Mobiluncus or Peptoniphilus with several other taxa, some of which are associated with bacterial vaginosis. High Nugent scores were associated with CST IV-B, whereas low Nugent scores were associated with CST IV-A.

While the nature of Ravel’s study precluded being able to observe changes in the 5 CSTs over time, Gajer’s study looking at temporal relationships in the vaginal microbiota over 16 weeks demonstrated that the microbiota of some women stayed in a stable state over time, while others more frequently transitioned between CSTs and most frequently to CST-IV, while all women remained asymptomatic. There was more change in species prominence during the menses than at any other time, but homeostatic properties returned the environment to baseline in most cases. It is hypothesized that differences in species composition may correlate with how vaginal communities respond to disturbances such as those related to human behaviors, the action of an individual’s immune system, or to exogenous invading organisms. As noted in one source, “a healthy (eubiotic) microbiome is resilient and can restore equilibrium when it undergoes oscillations. On the contrary, in other cases, host and environmental factors restrain the microbiota from compensating the alterations, and dysbiosis occurs.”26

CST-IV is the VMB most compositionally similar to bacterial vaginosis. CST-IV has been shown to be the predominant CST in approximately 40% of Black and Hispanic women, i.e., only 60% of African American and Hispanic women have been shown to have vaginal microbiomes dominated by what are traditionally considered “health promoting” Lactobacillus species.27 28 Anahtar et al have similarly found that non-Lactobacilli dominated vaginal microbiomes (nLDVM) predominate in 63% of healthy South African women, with 45% dominated by Gardnerella, L and, of 1107 rural postpartum Malawi women, 76% were found to have nLDVMs.29 30 Furthermore, 25% of asymptomatic women may not possess a Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota at any given point in time.31

As is clear from epidemiological studies, CST-IV is strongly associated with an increased risk for sexually transmitted infections including HPV, HIV and reproductive tract and obstetrical sequelae, perhaps through a mechanism of pro-inflammatory response via cytokine/chemokine signaling cascades. The various mechanisms by which a healthy or asymptomatic CST-IV state devolves into dysbiosis, BV and, importantly, microbiome dysfunction are proposed but not proven. Although Gardnerella may be detected in 50-60% of healthy, asymptomatic women, recent data suggest that specific clades or strains of Gardnerella species may be potentially more virulent than others and involved in BV development,32 with penile-vaginal sex found to increase G. vaginalis clade diversity. In addition, potentially important synergistic relationships between G. vaginalis, Prevotella bivia and Atopobium vaginae in BV pathogenesis may exist.33 Not all Lactobacillus species are necessarily beneficial or protective, with some strains of L. iners potentially more pathogenic and noted to predominate in less stable microbiomes which shift more readily into dysbiotic states.34 A 2015 study showed that L. iners-dominated VMB communities facilitated the penetration of HIV through the cervicovaginal mucus barrier (while L. crispatus-dominated vaginal microbiota acted as a hindrance to HIV penetration).35

Clearly, CST-IV is not monolithic, and “disentangling the diversity of CST-IV will be crucial for resolving the connection between these communities and vaginal health and will lead to improved targeted treatment outcomes.”36 The prevalence of dysbiosis of the VMB and BV in racial and ethnic minority groups worldwide has prompted an examination of the impact of psychosocial stress on the microbiome. In the vagina, by binding to glucocorticoid receptors in the vaginal wall, stress-induced cortisol is shown to inhibit the deposition of glycogen in a manner which restricts the Lactobacillus population, leading to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and mucosal immunosuppression.37 However, whether or not this inflammatory response is solely protective or solely harmful is a subject for debate, as it is proposed that people who experience higher levels of stress may have adapted nLDVMs that are able to create acidic environments without reliance upon Lactobacillus.38 As Ravel et al pointed out in their original study, “all communities [in these asymptomatic women] contained members that have been assigned to genera known to produce lactic acid, including Lactobacillus, Megasphaera, Streptococcus, and Atopobium. This suggests that an important catabolic function, namely the production of lactic acid, may be conserved among communities despite differences in the species composition.”39

A 2021 study by Wright el al. investigated heritability of L. crispatus. L. crispatus, consistently shown to be associated with a healthy, more temporally stable VMB, was determined to be heritable among European American women but possibly not among women of African descent.40 Women colonized by L. crispatus have lower risk of preterm labor, and pregnancy has been shown to be associated with low bacterial diversity and high levels of Lactobacillus, particularly L. crispatus.41 4243

An important resource about the VMB was written on behalf of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) in January 2022: a set of articles entitled “The Vaginal Biome I-V.” These articles summarize current findings and understanding of the VBM, mainly regarding areas relevant for clinicians specializing in vulvovaginal disease and are worth reading.44 45

The contents of the articles are as follows:

VMB I: Research development, Lexicon, Defining “normal,” and Dynamics throughout women’s lives.46

VMB II: Dysbiotic conditions: bacterial vaginosis, cytolytic vaginosis, DIV47

VMB III: Urogenital disorders: candidiasis, UTIs, STIs48

VMB IV: Reproduction and gynecologic cancers49

VMB V: Therapeutic modalities and research challenges50

Introduction

There are many abnormalities of the vaginal epithelium, including a variety of infections, microbiome imbalances, changes as a result of estrogen decrease, alterations after DES exposure in utero, or other medical events and underlying disease states. Many of these topics are covered elsewhere in the annotations.

Vaginal infections and microbiome imbalances

These are discussed in Annotation P, Vaginal Secretions, pH, microscopy, and other testing.

STIs are also discussed under cervicitis in Annotation M, Speculum exam and examination of the cervix.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis

This is discussed in Annotation P, Vaginal Secretions, pH, microscopy, and other testing: DIV.

Vaginal atrophy

This is discussed in Annotation P, Vaginal Secretions, pH, microscopy, and other testing: Atrophy/GSM

Vaginal endometriosis

This is discussed in Annotation N: The vaginal architecture.

Erosive lichen planus of the vagina

Classical, hypertrophic, and erosive lichen planus of the vulva are discussed in the Atlas of Vulvar Disorders.

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory disease that may affect, separately or simultaneously, oral and genital mucosa, skin, scalp, and nails.51 LP has been reported in the esophagus, conjunctivae, bladder, nose, larynx, stomach, and anus.52 The presence of vaginal epithelial disease distinguishes lichen planus from lichen sclerosus, in which vaginal involvement almost never occurs.53

Etiology

The etiology of lichen planus is not known. Recent data suggest the disease may be a T-cell mediated autoimmune condition involving activated T cells directed against basal keratinocytes.54 Weak circulating basement membrane zone antibodies have been shown to be present in 61% of patients with erosive lichen planus of the vulva.55 This activity represents response to altered self-antigens or heterogeneous foreign antigens.56 An association of oral and cutaneous LP with HLA-DR1 suggests a genetic component.57

A drug-induced form of this disorder usually develops insidiously and can affect any area of the body surface to cause or worsen LP; the disease may improve when the offending drug is withdrawn. Oral lesions occur in 30 to 70 percent of cases; the mucosa may be painful and ulcerated.58 Information on the percentage of vulvovaginal cases is lacking. Over one hundred medications that have caused LP or lichenoid eruption have been documented by case reports: methyldopa, penicillamine, quinidine, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, sulfonylurea agents, carbamazepine, gold, lithium, and quinine have all been associated with lichen planus.59 Drugs most frequently involved in induction of LP or worsening of LP are hydrochlorthiazide and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).60 Patients with mucosal LP are more likely to be on NSAIDs and beta blockers, although no association was found with oral LP and beta-blockers.61 Regarding the clinical forms and site of involvement, a statistically significant difference was only found for the clinical erosive form of oral lichen planus (OLP), seen more frequently in non-drug induced lichenoid reaction (DILR) (P = 0.04) and non-medicated OLP patients (P = 0.02) than in DILR OLP patients. Daily use of topical oral medication was reported by two (1.8%) OLP patients and one (1.3%) control subjects.62 In our experience, a trial of three to four weeks off a questionable drug offender results in clearance or significant improvement if the drug is involved.

Hepatitis C virus: The association of hepatitis C virus (HCV) with lichen planus is controversial, and a cause and effect relationship is uncertain.63

Prevalence

Oral LP is found in 0.5-2.3% of the general population.64 Vulvovaginal LP may occur in isolation, in association with oral involvement or in association with a generalized cutaneous eruption.65 Concurrent involvement of oral and genital sites, previously thought to be a low percentage,66 has recently been confirmed by biopsy in 31/41(75.6%) women in one study.67 Prevalence of vulvar lichen planus has probably been underestimated because physicians and dentists do not routinely examine the genitalia of their patients with lichen planus, and because genital lesions may be asymptomatic and subtle.68 In a specialized vulva clinic in Norway, 49/58 women with genital erosive lichen planus were found to have vaginal involvement with synechiae in 29 and total obliteration of the vagina in nine.69

Symptoms and clinical features

The typical symptoms of erosive vulvovaginal lichen planus are burning, pain, and pruritus, often accompanied by abnormal discharge.70 However, women with vaginal LP may indicate that they have had no symptoms such as itching, burning, pain, or discharge until the development of dyspareunia with pain on penetration and/or pain with speculum examination.

There may be no history of oral or vulvar disease in a woman with vaginal obliteration by asymptomatic LP. There may be a past history of oral or vulvar involvement, or there may be current oral lesions and/or vulvar lesions. Symptomatic women with vaginal LP often report irritative, yellow to serosanguinous discharge, spotting or post-coital bleeding. Women report that speculum examination and/or sexual relations have become painful, but often attribute these changes to the menopause.

Diagnosis

Vaginal LP is diagnosed by history of LP elsewhere, a history of dyspareunia, pain with speculum, vaginal lesions, vaginal scarring, and inflammatory discharge. Biopsy is important in clarifying the diagnosis if the characteristic signs are seen on pathology, but, depending on the stage of disease, may not be confirmatory. (See below). Cervical involvement can also occur in these patients.71

Physical exam findings will vary depending on whether vaginal LP is active or inactive and “burned out.” Active vaginal disease may or may not be accompanied by active vulvar disease: tender erosions in the vestibule and vulvar scarring (flattening or varying degrees of loss of labia minora, obliteration of prepuce and clitoris, and stenosis of the introitus from synechial formation. (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders). The scarring of vaginal LP is thought to distinguish it from desquamative inflammatory vaginitis.

With active disease, insertion of the speculum can be painful. Adequate examination, however, can usually be achieved with use of eutectic mixture of lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5% (EMLA) to the vestibule and hymenal ring for 15 minutes prior to speculum use. (If vaginal samples for pH and wet preparation can be taken with a Q-tip prior to application of the EMLA, a more accurate picture is obtained). With active disease, the vagina is erythematous, may have tender erosions or friable telangiectatic areas with patchy erythema on the sidewalls, or in the fornices. Varying amounts of yellow secretions with pH higher than 4.5 are seen in the vault. There may be synechial formation making opening of a speculum limited or impossible. If synechial scarring develops high in the vault, it causes narrowing of the vagina (telescoping). The cervix can be palpated beyond the narrowing, and may be involved with friable erythema.72 . Asymptomatic cervical involvement with LP has been documented.73 More advanced synechial formation can obliterate the vagina at any level, leaving a few centimeters of length or, in the worst cases, a dimple at the introitus.

If the disease is burned out, there may be no erythema, tenderness, or discharge, but vaginal scarring remains to cause dyspareunia and pain with speculum.

Pathology and laboratory findings

- Vaginal pH, microscopy

pH is elevated above 4.4 and may be as high as 7.0. Wet mount shows greater than one white blood cell per epithelial cell, reduction in squamous cells, the presence of immature parabasal cells, and reduction or loss of the lactobacilli.

Overgrowth of other flora may or may not be present. The wet mount of lichen planus may be identical to that of atrophy or desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV); a trial of adequate local estrogen is essential to differentiate these conditions.74 If increased white cells and parabasal cells persist after a four-week trial of adequate local estrogen, atrophy is ruled out or controlled. (See Microscopy section Principles of vaginal microscopy or synopsis illustration: pH and microscopy illustration for more information on using pH and microscopy to diagnosis.) - Biopsy

Achieving definite histological proof of LP in mucosal sites is difficult compared with classic cutaneous LP,75 and biopsy is often inconclusive.76 The biopsy should be taken from the edge rather than the center of erosion. Most often, the histology is returned as “lichenoid dermatitis” consistent with but not diagnostic of lichen planus.77 The diagnosis of these diseases is clinical, and strongly associated with other cutaneous lesions.78 Dermatology consult is essential for diagnosis and treatment of bullous disease or any condition in question.

Pathological findings in LP, first described in 1909, consist of irregular acanthosis of the epidermis, liquefactive degeneration of the basal cell layer, and a band-like dermal infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes. Colloid bodies, representing degenerate keratinocytes, are frequently seen in the lower epidermis and upper dermis.79 The inflammatory band at the dermo-epithelial junction is the most powerful predictor of LP; it is not seen with LS or eczema.80

Differential diagnosis

The discharge of LP may be difficult to distinguish from atrophy and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) since all three conditions produce small to large amounts of yellow, pus-like or serosanguinous discharge characterized by multiple white blood cells, parabasal cells, and loss of the lactobacillus. Atrophy responds to adequate local estrogen and treatment of atrophy helps to clarify the diagnosis. Persistence after treatment for atrophy of more than one white blood cell per epithelial cell and more than the occasional parabasal cell suggests DIV. If there is scarring in the vagina, with or without scarring and erosion in the vulvar vestibule, LP is suspected.

Overlap between lichen sclerosus and LP is well recognized on the vulva;81 vaginal lichen sclerosus has been reported in only one case.82

Agglutination of the labia minora from lack of estrogen is found in 1.8% of infants of 13-23 months but scarring attributed to atrophy in both children and adults is often caused by lichen sclerosus, not atrophy. Vaginal obliteration from atrophy is not reported in children or adults.

Bullous and cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction, graft-versus-host disease may also erode, scar, and/or obliterate the vagina. Vaginal adenosis may cause erosions or ulcers.

Association with squamous cell carcinoma

Malignant transformation of vulvar lichen planus has been reported but its incidence is unclear. No cases were found in 58 cases of erosive genital lichen planus evaluated in a Norwegian vulvar clinic between the years 2003-2009.83 Seven of 114 women developed vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and three women developed squamous cell carcinoma during a five-year study in the United Kingdom.84 There was one case of vulvar carcinoma among 44 women with LP in another case series.85 To date, vaginal cancer with vaginal lichen planus has not been reported.

Treatment

The treatment of stenosing vaginal LP is challenging to the physician, and treatment results are often disappointing, possibly because of the rigor demanded of both patient and physician. The intravaginal inflammation must be controlled to prevent scarring. Scarring existing at the time of presentation will need addressing after inflammation is treated if patency of the vagina is a goal. Subsequent to control of inflammation and release of scarring, ongoing close monitoring, intravaginal anti-inflammatory therapy, and maintenance of architecture using dilators or regular intercourse are all essential. Failures often occur with cessation of therapy by the patient herself or on the recommendation of her provider.

Intravaginal steroids, intramuscular triamcinolone, intravaginal tacrolimus

Intravaginal hydrocortisone

In our experience, intravaginal LP can usually be brought into control with

- 10-30% hydrocortisone in petrolatum, one gram vaginally nightly for 30 days with a follow up visit in one month.

Repeat evaluation in four weeks with speculum, digital exam, and wet mount will give information on regression of inflammatory lesions and friability, and, if the patient is improved, will show diminished white cells and parabasal cells on microscopy. If there is improvement, the hydrocortisone can be spaced out gradually with ongoing monitoring to once or twice weekly. If there is no improvement, the nightly therapy can be extended another four to eight weeks. With the use of intense intravaginal steroid, prophylaxis against Candida is often important. We use 150 mg of fluconazole weekly orally or combine clotrimazole 2% with the compounded hydrocortisone.

If there is inadequate improvement after 12 weeks of intravaginal hydrocortisone, it is important to ascertain that Candida is not present. Options we have used successfully to treat recalcitrant disease include:

- Prednisolone 5 mg vaginal suppository compounded, nightly for 30 days, then re-evaluation

- Intramuscular triamcinolone 60 mg IM, monthly for four months. This vastly under-utilized treatment modality is safe and effective for inflammatory dermatoses,86 especially in women who do not tolerate topical steroids. The depot of steroid gives peak levels from one to two days, which fall rapidly to a steady state. The steroid is gone by the end of the third week,87 but its anti-inflammatory effects remain long after its disappearance from the plasma. The episodic exposure may be less harmful than continuous low-dose oral therapy.88 Only one report in the literature links avascular necrosis with IM triamcinolone.89 Patients have (and must be counseled about this) adrenal suppression for 30-40 days following an intramuscular injection;90 but do not experience long-term suppression. The majority have normal adrenocorticosteroid function six weeks after their last injection.91

- Tacrolimus, 2 mg compounded vaginal suppository, nightly for 30 days, then re-evaluation. Tacrolimus is a topical calcineurin inhibitor immunosuppressant, which has been reported to be effective in erosive lichen planus.92 Its mechanism of action works through inhibition of the activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes. The advent of tacrolimus potentially heralds a new era of effective management of erosive lichen planus.

- Systemic treatments are surprisingly unhelpful, with poor response to methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine and hydroxychloroquine sulfate.93 Other immunosuppressives (mycophenylate mofetil, etanercept, adalimumab), and retinoids have been reported as helpful. In general, patients who are not responding to steroids or tacrolimus should be seen and managed in specialized units run by multidisciplinary teams in an academic center.

Steroid absorption and complications

Ultrapotent steroids have been in use for inflammatory dermatoses since 1988. When used appropriately, they have marked clinical efficacy and do not atrophy the skin or suppress the adrenal axis.94 (See Treatment Plans for an overview of use of steroids in the vulva and vagina). Unfortunately, drug manufacturers have not changed their package literature so that patients continue to be informed that ultra-potent steroids are unsafe for the genitals and must be limited to two weeks of treatment.

The vagina is an excellent route for steroid absorption.95 The mucosa of both the small intestine and the colon are statistically significantly less permeable to estradiol than human vaginal epithelium.96 However, there are no studies of corticosteroid absorption from the vagina. Topical usage of clobetasol propionate 0.05% is recommended not to exceed 50 g/week97 and a topical dose of 2 g per day of 0.05% clobetasol propionate can measurably suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal axis.98 Such doses per vaginam are not used in our practice; vulvar regimens involve a fraction of this amount.

The intravaginal treatment of vaginal lichen planus is often achieved with the much weaker hydrocortisone, and treatment regimens with ultrapotent steroids can be achieved using less than the level known to suppress the axis. When there is concern, a normal early morning cortisol level is reassuring. In our experience, the few patients who have come into question regarding cortisol abnormalities have had an endocrinopathy rather than ultra-potent steroid use as the source of their abnormal cortisol levels.

Release of intravaginal adhesions and vaginal dilator therapy

Intravaginal scarring can be addressed when active, inflammatory disease is brought under control so that no erosions or ulcers are present in the vagina. Scarring may involve total obliteration of the vault or partial strictures of varying degrees. It has been our experience with vaginal strictures of this nature, that dilator use is ineffective as treatment but is extremely valuable in maintenance, once the adhesions have been released operatively. Pre-operative preparation includes education for risk of recurrence of the lesions and the on-going need to manage the inflammation with topical steroids and dilators.

- Surgical release of adhesions: At the beginning of the procedure, we place a foley catheter and a rectal probe. We use a hand-held carbon dioxide laser without microscope under general anesthesia in the operating room. Small laser-compatible retractors, or a pediatric speculum disassembled to two blades are used for visualization of the vaginal adhesions. These are visible as grey-white fiber bundles seen when the vagina is put on stretch. A short burst of 12 watts releases these; the next bundle is located and the process continues with laser, sharp, and blunt dissection to eliminate as many adhesions as possible without endangering the bowel or bladder. At the end of the procedure, the vagina is filled with silvadene or petrolatum to prevent adherence over the next 24 hours.The patient is seen again within 24 hours to make sure that patency persists; any adhesions can be separated manually.

- Postoperative course and dilator use: During the first postoperative week, the patient uses two grams of estrogen nightly into the vagina with an applicator and is started on a small, rigid, Syracuse dilator nightly for 20 minutes.During the second week, she switches to the steroid or tacrolimus that brought her active disease into remission. She is seen every two weeks, advancing to a large dilator as appropriate. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance for genital exam, section on dilators). Her management will eventually lead to steroid use 2-3 times a week with dilator or intercourse 2-3 times a week. Our experience has been similar to the report of 13 women similarly treated who reported good relief, although to a varying degree, with some recurrence.99Other experts have used foam dilators covered with condoms inserted into the newly patent vagina. The labia minora are sewn together to keep the dilator in place; sutures and foam dilator are removed after 48 hours and high dose intravaginal steroids are started.100The combination of surgical dilatation, methotrexate, and local treatments with an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream and tacrolimus has also been reported effective in the treatment of patients with severe, stenosing vulvovaginal LP; the beneficial effect of methotrexate, in this study, extended also to oral lesions.101

Genital graft versus host disease

Introduction

Allogeneic stem cell transplant is being increasingly used for the treatment of leukemias, lymphomas, multiple myeloma, hemoglobinopathies, and other disorders that prevent the bone marrow from producing healthy cells. Graft versus host disease (GVHD) is the commonest complication of this life-saving treatment, in which the immunocompetent donor cells attack the recipient’s healthy tissues.

GVHD is classified into categories:

- acute (onset within 100 days of transplant);

- late onset acute (onset after 100 days but features consistent with acute disease only);

- classic chronic (may present at any time but only features of chronic disease);

- overlap (may present at any time with features of both acute and chronic GVHD)

The skin, GI tract, and the liver are the most commonly involved organs in acute GVHD (aGVHD). Thus, acute GVHD may present with diffuse maculopapular rash, profuse diarrhea and abdominal cramping, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and/or abnormal liver function tests. Other organ systems may also be involved, although less frequently.102

In contrast, the chronic form of GVHD (cGVHD) has variable multisystem clinical features that resemble many autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome or scleroderma. The chronic form is not considered to be an extension of acute disease but rather a separate entity. Most commonly involved are the skin, mouth, liver, lung, eye, joints, and GI tract. Most genital symptoms occur as part of chronic GVHD.

The initial report of genital involvement in cGVHD was in 1982, describing vaginal complications of scarring and closure in about 10% of the women diagnosed with cGVHD.103

Prevalence

GVHD is a common complication of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant and is thought to occur in its acute form in 9 to 50% of patients and in the chronic form in approximately 40% (range 6-80%). Chronic GVHD is more common in those who developed the acute form of the disease.

The risk of acute and/or chronic GVHD is highest in those with risk factors: immune mismatch (HLA disparity between donor and recipient); older age; sex disparity between donor and recipient; graft source (peripheral blood precursor has more risk than bone marrow or umbilical cord donations); CMV or EBV donor seropositivity.

Genital involvement has been reported in 12-70% of women with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, but many think that these numbers are underestimated due to lack of identification of the issues. Vulvar issues are most common, occurring in the majority of women with genital GVHD. The vagina is involved in close to half the women with vulvar problems, but may occur without vulvar disease, although vaginal only disease is the least common genital finding.104

Symptoms:

As the chronic form of GVHD has an impact on multiple organ systems, the symptoms are variable. Most common symptoms are from skin, affecting about 2/3 of the people with cGVHD: these may include erythema, plaques, telangiectasias and sclerotic changes. Changes to scalp, hair and nails are also common, including such symptoms as brittle, split or ridged nails, alopecia, loss of body hair, or premature graying of hair.

Other commonly involved organs are the liver (about 50% of patients), GI tract (about 30%), lung (about 50%), musculoskeletal (about 50%).

Genital symptoms are not uncommon and include itching, burning, pain to touch, and dyspareunia.105 Vaginal dryness has been found to be one of the most common complaints, impacting 54.6% of women in one report.106 However, as many women are hypoestrogenic as a result of the pre-transplant treatment with chemo and/or radiation, vaginal dryness may also be a symptom of hypoestrogenism.

Additionally, pain with intercourse is a common occurrence, reported in 51/180 women evaluated in a retrospective study.107

Rarely, more significant symptoms can result if vaginal scarring is occlusive. Hematocolpos has been reported (at least 28 cases in the literature). This condition may be associated with abdominal pain and cramping and usually requires urgent attention.108

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of genital chronic graft-versus-host disease is based on the history of allogeneic stem cell transplant and classic physical changes. Routine gynecologic assessment should be provided for all women with allogeneic stem cell transplant starting perhaps 3 months after transplant as tolerated. It is possible to have significant changes prior to reported symptoms. In one prospective cohort study, for example, almost 30% of the women were asymptomatic at the time of gynecologic visit and initial diagnosis. In this same study, median time to first confirmed sign was 6 months after transplant with a range of 1-30 months.109

There have been several proposed clinical classification systems to assist with diagnosis. The most common systems are based on the National Institutes of Health 2005 consensus criteria; a revised summary table is below.

Table O-1: Classification of Genital Graft versus Host Disease

| GRADE 1 (mild) | GRADE 2 (moderate) | GRADE 3 (severe) | |

| Symptoms | Itching, burning, swelling | Grade 1 symptoms and pain, intense burning, fissures | Grade 2 symptoms and dyspareunia |

| Signs | Redness, telangiectatic areas, white lines, erythema around Bartholin’s openings | Vulvovaginal synechiae, fissures, erosions | Widespread synechiae, partial or total vaginal stenosis, hematocolpos, spasticity of levators |

Table based on information in Knutsson ES et al.110, and Stratton P et al.111

If the symptoms and signs are mild (stage 1), the diagnosis is possible but not definite. With moderate to severe changes (stages 2,3), the diagnosis is presumed. If uncertainty persists, vulvar or vaginal biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis but this is not considered essential if the diagnosis seems clear.

Differential diagnosis

Fixed drug eruption, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and pemphigus.

Prevention and treatment

Patients with chronic GVHD with vulvar or vaginal symptoms should be cared for in cooperation with the transplant physician’s team.

Prevention

Prevention of some symptoms is possible with initial attention to estrogen supplementation in younger women with iatrogenic menopause related to pre-transplant treatment. Hormone replacement treatment should be discussed and offered to these women. In women who are already menopausal at the time of treatment, there may still be increased atrophic vulvovaginal changes and topical estrogen should be considered if appropriate.

Monitoring

Additionally, screening for cervical HPV related disease is advisable, as immunosuppression can be associated with an increased risk of abnormal Pap testing and the gynecologic form of GVHD may also be an independent risk factor for the development of cervical HSIL. One recent study noted abnormal cervical cytology in 26% of their women patients.112 Most recommend yearly Pap and HPV testing for at least 3 years after transplant. If negative testing to that point, it may be reasonable to move to every 3 year interval testing for cervical neoplastic disease.

Longer term evaluation for malignancy is also a critical component of care after allogeneic stem cell transplant. Previous studies have identified an increased risk of malignant neoplasm in these patients. Bernhard Heilmeiser et al, reported a cumulative incidence of malignancy of 4% at 10 years, 8.5% at 15 years, 14% at 20 years and 21% 25 years after transplant. This was compared to the age-matched control population and found to be six times higher (p<0.001). A variety of sites were involved, including skin (most common), breast, thyroid, oral and uterus/cervix.113

Treatment

The goals of treatment are several: relief of patient symptoms, control of current manifestations and prevention of progression of disease.

Once changes of gGVHD are identified, there are several approaches to care, depending on the severity of symptoms and signs.

- Estrogen topically: for those not already being treated with topical estrogen

- In mild cases topical steroids may be helpful in reducing symptoms and prevention of labial stenosis or other progressive scarring. Most prescribe high-potency steroids such as 0.05% clobetasol propionate or 0.025% fluocinolone acetonide.114

- In more severe or non-responsive cases, a topical calcineurin inhibitor such as tacrolimus ointment 0.2% (one to two applications daily) or cyclosporine may be tried.

- If any vaginal signs are noted (erosion, excess discharge, vaginal inflammation, vaginal synechiae), vaginal suppositories are recommended to prevent progressive scarring and possible vaginal occlusion. Most commonly, clinicians use hydrocortisone suppositories (25 mg), initially 1-2 times daily and decreasing to maintenance dosing of twice weekly administration.

- An alternative to vaginal suppositories of hydrocortisone is to apply hydrocortisone cream to a vaginal dilator or penile prosthesis.

- There is also some evidence that use of vaginal dilators on a regular basis and intermittent digital lysis of vaginal synechiae during office exams may also prevent progression of vaginal adhesions.

- Moderate to severe vulvovaginal changes and symptoms may benefit from oral steroids (e.g. prednisone 20-30 mg/day tapered after 2 weeks to a smaller dose such as 2-5 mg daily or q.o.d).

- If vaginal occlusion or labial adhesions are present, a surgical repair may be needed. This should be ideally performed by a gynecologic surgeon with expertise in vulvovaginal adhesions. CO2 laser may be particularly useful for lysis of adhesions due to the low risk of surrounding tissue damage compared to cautery.115 116

Vaginal fixed drug eruption

For vulvar fixed drug eruption, see Annotation F: The vulvar architecture and Atlas of Vulvar Disorders.

Introduction

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is an uncommon reaction to drug and occasionally food ingestion that recurs in the same site or sites each time the drug is administered. Since the genital area in women is a common site of eruption, FDE may present as acute, recurrent, or chronic vaginitis that resolves rapidly when the offending drug is withdrawn.

Prevalence

Vaginal fixed drug eruption is rare.

Etiology

Fixed drug eruption is a type of allergic reaction to a medicine. Usually just one drug is involved, although independent lesions (patches) from more than one drug have been described. Cross-sensitivity to related drugs may occur and there are occasional reports of recurrences at the same site induced by drugs that appear to be chemically unrelated. Sometimes the inducing drug may be re-administered without causing reappearance of the patch(es) and there may be a refractory period during which no reaction will occur after the occurrence of FDE. The pathogenesis of FDE remains undetermined. However, results of a recent study suggested that activation of effector memory T cells residing in the epidermis contributes to tissue injury.117

The most common causative agent is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.118

The number of drugs capable of causing fixed eruptions is large and includes over-the-counter medications as well as prescription drugs. Most FDE lesions are due to the following:119

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen)/phenacetin and other pain killers

- Tetracycline antibiotics: doxycycline, minocycline

- Sulphonamide antibiotics including cotrimoxasole (Bactrim, Septrin, Apo-Sulfatrim, Trimel, Trisul), sulfasalazine (Colizine, Salazopyrin)

- Acetylsalicylic acid/aspirin

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) including ibuprofen

- Sedatives including barbiturates, benzodiazepines and chlordiazepoxide (Novapam)

- Hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan, Scopoderm) – see halogenodermas

- Dapsone

- Phenolphthalein (an old-fashioned laxative for constipation)

- Quinine (Q-200, Q-300, Quinoc), taken for leg cramps)

Symptoms and clinical manifestations

The eruption appears usually within 30 minutes to 8 hours after drug exposure. The diagnostic hallmark is its recurrence at the previously affected sites. Characteristically, fixed drug eruptions recur at the same sites with repeated exposure to the offending drug. In one group, 24/28 (89%), the lesions were vulvar only; in 3/28 they were vulvovaginal.120

Mucositis progressing to erosion and ulceration has been documented in one study.121

Diagnosis

There are no definitive laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis of FDE. Oral provocation with the suspected agent is the only reliable method in most cases.122 The clinical pattern of FDE may provide useful information to determine the most likely causative drug, especially when the details of the drugs to which the patient has been exposed are known. Fixed drug eruption is characterized by well-circumscribed, erythematous patches and plaques, occasionally associated with bulla formation. The lips, genitalia, and sacral area are favored involvement sites; however, FDE lesions can appear on any part of the body.123

Treatment

The main goal of treatment is to identify the causative agent and avoid it. In addition, symptoms must be treated. Systemic antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may be all that are required. In cases in which infection is suspected, antibiotics and proper wound care are advised. Desensitization to medications has been reported in the literature, but this should be avoided unless no substitutes exist.124

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure

Abnormalities of the cervix related to DES are discussed in (Annotation M: Speculum exam and examination of the cervix)

A brief history of DES and vaginal structural changes are discussed in (Annotation N: The vaginal epithelium).

Vaginal adenosis, which is often DES related, is discussed below. (Annotation N: The vaginal epithelium).

Vaginal adenosis

Cervical adenosis is discussed in Annotation M: Speculum exam and examination of the cervix.

Introduction

The vaginal canal is usually lined with non-keratinized squamous epithelium without glands. When glandular epithelium is present in the vaginal canal, this is considered vaginal adenosis. The glandular cells may be superficial, replacing the usual squamous layers or glandular cells may occur in the submucosal area. Different types of glandular epithelium may be identified, most commonly mucinous with similar appearance to endocervical cells. Tuboendometrial cells have also been identified.125

Vaginal adenosis was first described in 1877. Over the course of the next 90 years, multiple cases were reported in the literature (about 60 case reports). The condition was thought to be analogous to changes of the cervix, such as cervical ectropion or endocervical polyps. Many of the reported cases presented with benign findings such as vaginal cysts. However, at least eight women with “malignant vaginal adenosis” were reported in this early literature.126

In 1971, things changed with the report of the association of in utero DES exposure and vaginal clear cell carcinoma.127 Over the next few years, multiple cases of DES-exposed young women with adenosis and vaginal adenocarcinoma were reported. Subsequently, women with squamous dysplasia in the region of vaginal adenosis were also identified.128 Women with the potential of exposure in utero to DES in the United States are now, in 2024, aged 73 to over 90.129

Prevalence

The prevalence of vaginal adenosis is unclear as the changes are not commonly identified at the time of usual pelvic examination. Careful investigation under magnification (colposcopy) may identify some changes, but that procedure is rarely undertaken without indication. Vaginal adenosis has been identified in more than 60% of women with DES in utero exposure, although there is a broad range depending on the gestational age. Adenosis is more common (>90%) when DES was taken by the mother before 8 weeks gestation. Estimates are lower (<10%) when DES was taken after 15 weeks.130

Etiology

The cause for adenosis remains obscure although many postulate that a change in embryonic development is responsible. Studies in mice show that early gestational exposure to estrogens can prevent the transition of the original Müllerian epithelium into normal squamous epithelium.

DES exposure is clearly associated with increased risk of vaginal adenosis. However, additional causes have been reported in the literature, including vaginal 5-FU and laser treatments131. There are also reports after sulfonamide-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and after tamoxifen exposure.132

Symptoms and clinical features

The majority of women with adenosis are asymptomatic. For those with symptoms, there is considerable variation, with reports of pain, itching, vaginal discharge, or ulcers. Postcoital or other intermenstrual bleeding has also been reported.133

Diagnosis

Vaginal adenosis is usually diagnosed on colposcopy. The appearance is variable and may range from a simple area of glandular epithelium to patchy, red erosions or ulcers. Submucous adenosis may be suspected by palpation, often as a small gritty nodule. The majority of lesions are in the upper 1/3 of the vagina, although areas of adenosis have been reported the length of the vaginal canal. Unlike DES associated adenosis, the vaginal adenosis related to Stevens-Johnson syndrome occurs more commonly lower in the vaginal canal.

Definitive diagnosis is made by biopsy and histology examination.

Differential diagnosis

Erosive lichen planus, fixed drug eruption, erythema multiforme and bullous skin disease.

Treatment

There is no clear recommendation regarding treatment. With DES exposed women, metaplasia with gradual progression of columnar to squamous epithelium is documented. Accordingly, benign adenosis without atypia on biopsy is usually followed without treatment. Others have advocated for treatment, given the association of vaginal adenosis with virtually all clear cell carcinomas of the vagina.134

For the small percentage of women with symptoms, treatment may be preferred. Excision, cautery, and laser have all been used to treat vaginal adenosis with varying success.135

Vaginal Condyloma

Introduction

Condyloma, the visible papules and plaques that may be noted with HPV infection, are most commonly seen on the vulva and perianal areas. Vaginal lesions may also occur, although these are usually not noted by the patient.

Prevalence

Uncertain, as diagnosis requires examination, but probably common

Etiology

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is the causative organism. The low-risk types 6 and 11 are the most common, although high risk types may also cause papillary lesions.

The major risk factor is exposure to the virus through sexual activity. Extensive disease is more likely in those who are immunocompromised, diabetic, or smokers.136

Symptoms

Most women have no symptoms related to vaginal lesions although many will note and report lesions in other lower genital areas. Vaginal discharge may be reported but this is likely usually related to associated bacterial vaginosis, which is commonly identified in women with HPV.137

Diagnosis

Physical examination is required for diagnosis. Women with condyloma of the vulva, perianal or inguinal areas should have a speculum examination to assess for vaginal lesions. The lesions are usually soft and papillary although warts may be flat. If the diagnosis in not clear on examination, vaginal biopsy is indicated.138

Additionally, screening for other sexually transmitted infections should be considered at this time.

Differential diagnosis

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN), benign papillary changes of the vagina

Treatment

For women with vaginal condyloma, observation is an option; about 40% will resolve over time without treatment. If the patient opts for treatment or if the lesions persist, then there are several options:

- Trichloroacetic acid applied by the clinician; this should be considered for limited vaginal disease but has not seen studied for extensive disease

- 5 fluorouracil has been shown to be effective for papillary vaginal lesions using a 5 day patient applied course. However, medication side effects on the vulva are common, including irritation, pain, and erosion or ulcer formation.

- Imiquimod has not been extensively studied for vaginal condyloma. However, this medication has been evaluated for the treatment of VaIN and is in common usage for that purpose. Many clinicians offer imiquimod for vaginal condyloma as well, as the medication is generally well tolerated.139

- CO2 laser can be used for vaporization of the lesions and is a reasonable option especially in extensive disease.

- Electrocautery may be considered but may be less well tolerated than CO2 laser.

- Extensive lesions may require initial surgical excision to debulk.

Treatment is acceptable in pregnancy and should be considered for those with potentially obstructive lesions. Laser would be preferred rather than excision.140 141

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN)

For cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN/cervical HSIL): (Annotation M: Speculum exam and evaluation of the cervix)

For vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN): (Annotation F: The vulvar architecture) and the Atlas of Vulvar Disorders.

*This topic is also covered in Annotation N: The vaginal architecture

Introduction

VaIN is the presence of squamous cell atypia in the vaginal epithelium in the absence of invasion. The condition is further classified by the level of atypia in the epithelial layer. Using the terminology that became common in the 1980s, if the changes are confined to the lower 1/3 of the epithelium, it is VaIN 1 (formerly mild dysplasia); if involving the second third, VaIN 2 (formerly moderate dysplasia) and if involving more than 2/3 of the epithelium, VaIN 3 (formerly severe dysplasia).

In 2012, a working group was established to review and update terminology of lower genital tract neoplasia. They recommended a single unified nomenclature for all of the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)-associated pre-invasive squamous lesions of the anogenital area.142 Accordingly, this terminology includes low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), including previous VaIN 1, and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), including VaIN 3. Previous VaIN 2 may be allocated into either LSIL or HSIL depending on pathology review and possible additional staining. HSIL is considered to be a pre-invasive lesion although spontaneous regression can occur.

Prevalence

Uncommon.

The true prevalence is not known, although the frequency of diagnosis has increased over the years with improved access to Pap/HPV testing and colposcopy.143 Estimates of incidence are usually about 0.2-0.3/100,00 women in the US.144

Etiology

The majority of cases of VaIN are associated with HPV. High-risk types 16 and 18 are the most common subtypes identified.

Other risk factors include:

- Other HPV-related cancers or precancers. The majority (50-90%) of patients with VaIN have had previous or current intraepithelial neoplasia or cancer of the cervix or vulva.

- Positive HPV testing from the cervix. A recent study showed that women with cervical HPV 16 infection had an increased hazard ratio for the development of VaIN2+, HR = 23.5. The 10 year cumulative incidence of VaIN 2 in these women was 0.2%.145

- HIV infection. A recent study confirms the increased risk of VaIN in women living with HIV, even if reliably in medical care and on retroviral medications. They may also present with multifocal disease at a younger age.146

- Cigarette smoking. There is some evidence to suggest that tobacco use is a co-factor in the development or persistence of VaIN.147

Symptoms and clinical presentation

VaIN is generally asymptomatic. Rarely post-coital bleeding or heavy vaginal discharge can be present.

Rarely a lesion is noted at the time of a pelvic exam, usually patchy white. However, most commonly, an abnormal Pap test is the trigger for full evaluation for VaIN.

Diagnosis

Careful clinical inspection of the vagina is a reasonable first step, looking for color changes (generally thickened, appearing white) or rarely, ulcerations. The majority of the lesions are at the top of the vagina, often in proximity to the cervix (if present) or the vaginal apex (if previous hysterectomy).

Colposcopy of the entire vagina is indicated for

- Abnormal Pap test in a woman with previous hysterectomy

- Abnormal Pap test in a woman with the cervix present but no cervical lesions on colposcopy that could explain the Pap findings

- Any woman with worrisome vaginal lesions or ulcerations

Colposcopic technique is similar to that of the cervix with application of acetic acid and use of a green filter to enhance vascular changes. However, it is more technically challenging due to the large surface area and multiple vaginal folds. Many clinicians use Lugol’s solution, which may help visualization of the large surface area of the vagina. Occasionally, especially after hysterectomy, the base of vaginal folds cannot be well visualized. Pressure with q-tips can be helpful to open the space for observation. Occasionally a skin hook may be used to enhance visualization.

Definitive diagnosis is based on biopsy. A biopsy should be obtained from any concerning lesion identified on colposcopy.

Differential Diagnosis

Condyloma, previous scarring from surgery or childbirth, adenosis, vaginal polyps

Treatment

Low grade lesions on Pap and biopsy are generally managed conservatively with observation.

High grade lesions are generally treated based on the risk for progression to cancer, estimated between 2 and 12%.148

Treatment modality should be based on the lesion size, multifocality, and patient co-morbidities. Most common options are

- Surgical excision, preferred if there is suspicion for cancer or additional histology specimens are required or the lesion cannot be adequately visualized

- Local ablation, generally with CO2 laser, especially for those with multifocal disease

- Topical agents such as imiquimod and 5FU may be used as primary treatment for some patients

- Intravaginal radiation is rarely used but may be considered for women with extensive disease who are poor surgical candidates.149

Recurrence rates are high after treatment, so careful long term follow-up is recommended regardless of the primary treatment method chosen. In a 2016 report of 205 patients, progression to vaginal cancer was reported in 5.8% of patients (mean follow-up 57 months). Progression was associated with VaIN 3 on original biopsy and for women with previous hysterectomy.150

Vaginal Cancer

Introduction

Cancer identified in the vagina may be primary, disease from local spread, or metastatic. Most common is metastatic disease, making up 80% of cancers identified in the vagina. Most of these cancers are metastatic from the endometrium or cervix. Metastatic disease may also occur, although less commonly, from colorectal cancer, breast cancer, renal cell cancer, or melanoma.

Local spread may occur from the cervix or the vulva as well as the bladder or rectum. By definition, according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, if the cancer is identified on the vulva, it is considered of vulvar origin. Similarly, if the external cervical os is included in disease, the primary site is considered to be cervical.

True primary vaginal cancers make up 20% of the cancers identified in the vagina.

The most common type is squamous cell carcinoma, making up 85-87% of the primary cancers. These cancers are most commonly located in the upper 1/3 of the vagina. HPV can be identified in over 50% of cases. A previous study of protein patterns in vaginal and cervical cancer showed that the gene expression is fairly homogeneous, suggesting similar origins.151 The average age at time of diagnosis is 67.

Adenocarcinoma of the vagina is the second most common type, accounting for about 9% of the cases. As most of the adenocarcinomas have been DES-related clear cell carcinomas, the mean age is 22, although cases have been reported in older women. Recurrences may occur as late as 20 years after the original diagnosis.152

Melanomas may occur primarily in the vagina, about 1% of the primary vaginal cancers. These are often located on the anterior vaginal wall in the distal 1/3 of the vagina. Average age of diagnosis is about 60.

Sarcomas may also occur in the vagina, although rare. Sarcoma botryoides is the most common of the sarcomas, occurring in young children. The average age of diagnosis is 3 years.

Prevalence

Vaginal cancer is relatively uncommon. The American Cancer Society estimated that there would be 8870 cases in 2022 with 1630 deaths.153] In 2018, the rate of vaginal cancer in the US was 0.8/100,000 for black women, 0.6/100,000 for white women and lowest for Asian/Pacific Islanders at 0.4/100,000.154

Symptoms and clinical features

Vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom of vaginal cancer, commonly post-coital or postmenopausal. Occasional women will note a vaginal mass. About a quarter of women will have no symptoms.

Diagnosis

The history is an important component of making the diagnosis. Risk factors should be assessed. These include:

- previous history of HSIL or cancer of the cervix, vulva, or anus. There is good evidence that previous HPV related neoplastic disease increases the risk of vaginal cancer. One large study from Sweden showed that women treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 are at higher risk of developing invasive cervical or vaginal cancer for at least 25 years after initial diagnosis.[Strander B, Andersson-Ellström A, Milsom I et al. Long term risk of invasive cancer after treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: population based cohort study. BMJ 2007; 335(7629): 1077[/efn_note]

- smoking

- HIV or other immunosuppression

- DES exposure155

The examination should include evaluation of the inguinal nodes. A careful inspection of the vagina is required, which will involve some manipulation of the speculum to allow a view of the entire surface of the vaginal canal. Vaginal palpation to assess for masses or grittiness is then followed by a bimanual exam to assess the other pelvic organs. Rectovaginal examination can help to look for rectal involvement or parametrial thickening.

If suspicion is high but a lesion is not initially noted, vaginal cytology and colposcopy may be helpful in identifying the area of concern.

Any area of abnormality should be biopsied, as histology makes the definitive diagnosis of cancer.

Treatment

Women with vaginal cancer should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for clinical staging, diagnostic imaging and treatment planning.

Stage I cancers are often treated with surgery although larger lesions or cancers low in the vagina may be treated with radiation. For women with Stage II to IV disease, chemoradiation is currently the preferred approach for most types of vaginal cancer.156

Bullous erythema multiforme

See this area in the Atlas: Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS),toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

Sjögren syndrome

Introduction

Sjögren syndrome (SS) is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease in which the salivary and lachrymal glands are progressively destroyed by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Patients with SS will complain of dryness, grittiness, or the sense of having a foreign body in the eye due to a decrease in the production and quality of tears. They will also complain of a very dry mouth, difficulty speaking for long periods, hoarse voice, dry throat, and an increase in dental caries. Chewing and swallowing are also affected by the decreased production of saliva. Peripheral neuropathy is present in 10% to 60%.157

Prevalence

According to the Sjögren Syndrome Foundation, the condition affects as many as 4 million Americans. Women are affected 10 times more often than men are. The average age of onset is upper 40’s, but the syndrome may develop at any age.

Symptoms and clinical features

In addition to the dry eyes and dry mouth described above, vaginal dryness and dyspareunia are also complaints; in fact, chronic dyspareunia can be a presenting feature of Sjögren, predating ocular or oral symptoms by many years in a few reported cases.158 There are more complaints of both dyspareunia and vaginal dryness in women with primary SS than in healthy patients. In a study of 36 female outpatients with SS and 43 healthy women who were in a control group, all with a comparable frequency of sexual activity, dyspareunia was present in 61% of primary SS patients and 39% of women in the control group.159 Such a symptom was significantly more frequent in postmenopausal SS patients than in women in the control group. Vaginal dryness was found in 52% of SS patients and 33% of controls. When the pre- and postmenopausal patients were compared, it was found that vaginal dryness was reported in 33% of premenopausal patients compared with 72% of the post-menopausal patients.

Etiology

Although insufficient vaginal lubrication has many causes, researchers looking specifically at the vaginal tissue of SS patients found that they all had perivascular infiltration with chronic inflammatory cells.160 It is believed that this lymphocytic vasculitis could be involved in the development of the dyspareunia caused by a dry vagina. Therefore, any increase in vaginal dryness in women with SS beyond that associated with estrogen deficiency or vaginal infection may be related to an underlying autoimmune effect of SS on the vascular supply to the vagina.

Treatment

There is no treatment specific for vaginal manifestation of Sjögren. The disease itself is sometimes treated with immunosuppressant drugs; whether these affect vaginal dryness symptoms is not known. Withdrawal of any drugs that may induce xerostomia such as tricyclic antidepressants or atropine may be considered. The compound polycarbophil, found in Replens (LDS Consumer Products, Cedar Rapids, IA) and Durex Sensilube (SSL International, Knutsford, Cheshire, UK) has the ability to cling to epithelial surfaces and to be effective for up to 72 hours.161 Furthermore, it releases water that rehydrates the epithelial cells and keeps the vagina moist for longer periods. Estrogen creams, which can increase capillary blood flow to the vagina and vulvar area, and hormone replacement therapy, are also helpful.

Radiation injury

Introduction

External beam radiation therapy and brachytherapy for gynecologic tumors (endometrial and vaginal) and for rectal cancer162 can cause radiation injury of the vulva and vagina with symptomatic shortening and narrowing of the vagina, dryness, and dyspareunia in up to 70 percent of patients.163 164 Vaginal stenosis after treatment for cervical cancer occurs in 55% of post radiated patients.165 Radiation damage involves fibrosis, vascular toxicity, neurotoxicity, and psychological factors.166

Symptoms and clinical features

External beam radiation to the vagina initially causes extreme pain and moist desquamation to the entire genital/perineal area. There is loss of pubic hair. Later changes manifest as circumferential whitening and rigidity of the vaginal vault (fibrosis) with foreshortening or stenosis. Cystitis, proctitis, and rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistulae are also possible.

Treatment

Many women receiving radiation therapy do not receive education about potential sexual side effects and resultant pathology, including vaginal stenosis, has received little attention. Significant sexual dysfunction for treated women may be a consequence.167 If not addressed, the problems compound over time.168

To prevent vaginal stenosis, some clinicians have recommended dilator use169 following radiation treatment and topical estrogen cream to prevent and treat symptomatic shortening and narrowing of the vagina.170 The UK Gynaecological Oncology Nurse Forum recommends using vaginal dilators three times weekly for an indefinite time period.171

A 2010 Cochrane review, however, raises controversy regarding dilator use. During or immediately after radiotherapy, dilators in two reported cases caused recto-vaginal fistula.172 In the review, the authors found no persuasive evidence from any study to demonstrate that dilator use prevents stenosis,173 including one randomized, controlled trial that showed no improvement in sexual scores in women who were encouraged to practice dilation. The review authors suggest that gentle vaginal exploration might separate the vaginal walls before they can stick together. Some women may benefit from dilation therapy once inflammation has settled, but there are no good supporting data.

If there is an intact urinary and intestinal tract, some experts offer surgical treatment to widen the vagina with laterally placed flaps.174 175 However, neovaginal reconstruction following pelvic irradiation is a difficult procedure that has a high risk of complications and limited success, since fibrosis can be ongoing after the reconstruction.176

Because vaginal stricturing is common after radiation therapy, and because good alternatives to dilators do not exist, we continue to work in our practice with local care, adequate local estrogen, and dilators. Treatment starts with education. A woman needs to know to ask what to expect regarding physical changes, discomfort, and sexual functioning, if this information is not offered. She needs to understand that continuing sexual function in the presence of vaginal stricturing involves a lifetime commitment. During the acute treatment period, comfort measures include sitz baths, moisturization with a film of vaseline, and adequate pain control. Vaginal intercourse may substitute for the dilator use, but therapeutic intervention appears to be superior to regular sexual intercourse alone.177 In a woman who already has radiation changes, comfort measures with sitz baths and moisturization with a film of Vaseline, regular vaginal dilatation and topical estrogen cream may also be useful.

Dilators are prescribed with instruction, initial demonstration to the patient, and returned demonstration from the patient. It is never helpful to give a set of dilators without this education. A dilator must be rigid in order to do the job, not soft and flexible. An appropriate size is selected with circumference that fits snugly with lubrication. Xylocaine 5% ointment is used prior to insertion. Use of xylocaine is essential to prevent sensitizing pain with vaginal insertion. In order to achieve dilation, the dilator must stay in place at least 20 minutes three times weekly. We suggest reading or television during this time in the evening or at a quiet portion of the day. Once the dilator fits in loosely and comfortably, the patient advances to the next size. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance of genital exam, section on dilators).