Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy and other testing

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationDespite the wide variety of etiologies for vulvovaginal symptoms, women and their providers continue to assume at the onset of itching, burning, dyspareunia and/or change in discharge, that “vaginitis,” usually Candida or bacterial vaginosis (BV), is to blame. Many women, under this assumption, inaccurately self-diagnose and self-treat.1 Many clinicians, under this assumption, still treat by telephone diagnosis, an unreliable practice.2 Patient self-testing for many conditions is being evaluated by researchers, but there is no standard of care that supports these methods as yet.3 4 5

Successful diagnosis and treatment of vulvovaginal disease is based on the importance of not making assumptions, of taking a careful history, and doing a careful examination, beginning with inspection of the vulvar skin for changes in architecture, color, texture, and integrity. (See Annotation H describing alterations of vulvar anatomy and epithelium (the morphologic approach) to identify etiologies of symptoms that may be outside the realm of “vaginitis.”) Next, precise symptom location and mapping with the Q-tip test are essential. The final information leading to correct diagnosis is obtained with pH and microscopic examination of the vaginal secretions. There are many efforts underway to create more accurate point of care tests that will reliably give a diagnosis on the spot,6 but pH, KOH, and microscopy give information that is outside the realm of commercial testing and the elimination of microscopy in clinical practice would be an injustice to patients and providers, alike.

In the past, clinicians were trained to diagnose by inspection only. However, the appearance of vaginal discharge is extremely unreliable and should never form the basis for diagnosis.7 Examination and diagnostic studies are necessary in all women. It is important to remember that conditions that affect the vulva may also manifest in the vagina and vice versa. In addition, multiple conditions may be present simultaneously. On the other hand, if the pH and wet mount microscopic evaluation are normal, many conditions can be automatically ruled out.

Complaints suggesting a vaginal etiology may include discharge, itching, irritation, pain, and dyspareunia in varying degrees. Start your history with your mind a clean slate, disregarding diagnoses in the patient’s chart. Ask about symptoms, not diagnoses, and obtain a time line of what happened first, what was done, whether it helped, and what happened next. (Anno B: The patient history) Patients frequently indicate that a treatment “didn’t work,” but close questioning may show that a steroid or anti-fungal provided significant relief at first, but the symptoms returned. Patients often do not allow adequate treatment time for a medication to “work.” Few know that fluconazole acts promptly against the Candida organism, but resolution of the inflammation takes far longer: days to weeks.

It is essential, in addition to the vaginal symptom time-line, to consider:

- A new sexual partner. A new sexual partner increases the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted diseases. In addition, with increased frequency of sexual relations with a new relationship, Candida albicans is common, as is bacterial vaginosis.

- Hygienic practices (e.g. daily use of panty liners, feminine products). Do a careful review of the woman’s personal practices: bath soap and method of washing, menstrual protection, use of any products in the vulvar area, clothing practices, daily physical activities (biking, horseback riding) that may affect the vulva. Exogenous agents may cause vulvar symptoms mistakenly attributed to an infectious source.

- Medications (prescription and nonprescription) used. Antibiotics and high-estrogen contraceptives may predispose to Candida vulvovaginitis. Increased physiologic discharge can occur with estrogen-progestin contraceptives leading a woman to suspect infection. Irritant reactions to topical products or medications may cause pruritus unresponsive to antifungal agents.

- Relation of symptoms to menses. Candida vulvovaginitis often occurs in the premenstrual period, while trichomoniasis often flares during or immediately after the menstrual period. Hormonal states related to absence of menses in lactating women cause vaginal atrophy as severe as in the postmenopausal period, though temporary.

- Presence of abdominal pain suggestive of pelvic inflammatory disease. Suprapubic pain is suggestive of cystitis. Both suprapubic and abdominal pain, uncommon with vaginitis, may represent symptoms requiring a separate work up, including ultrasound.

- Hormonal therapy in menopausal woman. Absence of adequate estrogen may cause uncomfortable vaginal atrophy. Systemic oral or topical hormonal therapy may still be inadequate for vaginal estrogen levels, leading to dyspareunia. In addition, use of estrogen in the postmenopausal woman can lead to Candida.

History alone does not allow a definitive diagnosis since there is considerable overlap among the different disorders.8 Examination and some diagnostic studies are necessary in all women.

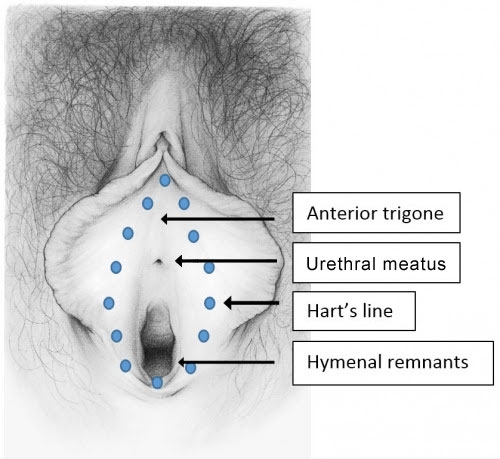

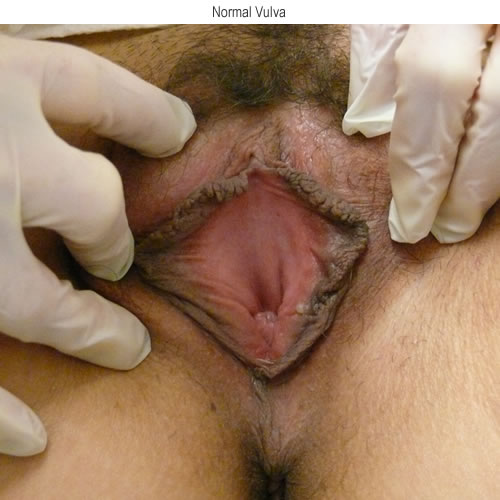

Steps of the physical exam have preceded this annotation in Annotations C (The targeted, non-genital exam), E (Detailed vulvar exam), F (The vulvar architecture), H (The vulvar epithelium), and I (Pain and symptom mapping), as well as the Annotation M (Speculum exam and exam of the cervix), N (The vaginal architecture), and O (The vaginal epithelium). Vaginal discharge may be present at the introitus, may coat the tissue of the vestibule, or may only be assessed on speculum exam.

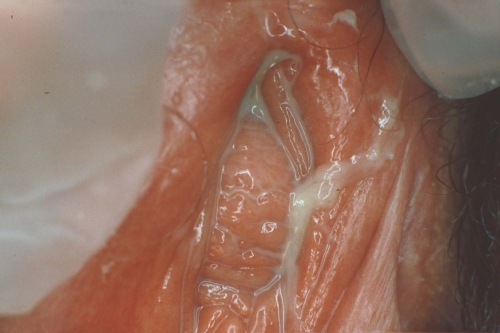

See the following photographs for a sense of visual inspection of the vestibule:

Diagnosis of a specific type of “vaginitis” should never be made based on the appearance of the discharge alone. Clinicians are classically taught that certain characteristics of discharge can be linked with particular conditions. For instance, we expect that discharge can be white and clumpy with yeast, greenish and purulent with cervicitis or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), greenish-yellow and frothy with trichomonas, thin, homogeneous, gray-white and malodorous (fishy-smelling) with bacterial vaginosis, or tan or brownish, with the presence of old blood. However, the appearance of both normal and abnormal discharge can be highly variable and all of the conditions listed can be found in the absence of significant discharge.

Origin and composition of vaginal secretions

Secretions from the vagina in women of reproductive age are normal. They do not, however, originate from the vagina, which has no glands.

Fluid enters the vaginal cavity by transudation through the vaginal epithelium as 90–95% water. It contains secretions from Bartholin’s and Skene’s glands of the vulva, located close to the vaginal orifice, cervical mucus, endometrial and tubal fluids. In addition, the fluid may also contain some residual urine and exfoliated epithelial cells. As a consequence, organic and inorganic salts, urea, carbohydrates, mucins, fatty acids, albumin, immunoglobulins, and other macromolecules can be found in vaginal fluid. Fluid entering the vagina, as well as the vaginal resting fluid volume, are subject to inter- and intraindividual variability and are affected by a number of variables, such as age, phase of the menstrual cycle, and sexual stimulation.9.

Function of normal vaginal secretions

The well-established function of the vaginal fluid is to moisten the vaginal epithelium.10

Quantification and characteristics of normal secretions

Amount: Normal, physiologic discharge varies in amount from about one to 4 mL in 24 hrs11 and is heaviest at ovulation (day 14 of the 28 day menstrual cycle), and lightest on days 7 and 26.12

Table P-1: How normal discharge changes: relationship between the menstrual cycle hormones and vaginal secretions. 13

| Cycle Day | Estrogen | Progesterone | Secretions |

| 1-7 | Low | Very low | Menstrual flow begins and ends.Few secretions; dryness |

| 8-13 | Rises and peaks | Very low | Secretions increase |

| 14-16 | Drops sharply | Starts to rise | Ovulation; maximum clear mucus |

| 17-25 | Second small rise | Peaks | Secretions thicken and turn yellowish |

| 26-1 | Drops slowly | Drops slowly | Secretions diminish to low point |

Odor: Normal discharge has a mild, inoffensive odor (similar to sour milk) from the presence of lactobacilli. Its color ranges from white to clear and it may dry in a small white or yellow plaque on underwear. Discoloration of discharge, alone, should never be the criterion for diagnosis and treatment without evaluation first.

Other characteristics: Many women are unaware that vaginal discharge is a normal, physiologic phenomenon, and believe that they should be completely dry. They wear protective panty liners and may use feminine hygiene products in an attempt to do away with any discharge or odor, sometimes promoting irritation of the skin. In addition, many women are not aware that normal secretions can appear clumpy.

Upon noting clumpy, white discharge after a digital exam of the vagina, a woman immediately assumes yeast is present. Clinicians, too, often interpret normal, clumpy secretions as Candida. At mid-cycle secretions become abundant, clear, stretchable, like egg white, exhibiting the phenomenon of spinnbarkeit (German, ability to be spun).

Only such mucus appears to be able to be penetrated by sperm.

Hormonal changes: In postmenopausal women not on hormone replacement, whose estrogen states are low and stable, there is usually very little vaginal discharge. In some states of atrophy, women may complain of a sticky, yellow discharge. (Genitourinary syndrome of menopause). Low estrogen states causing changes on pH and wet mount may arise with lactation and other hormonal changes. Educating women about normal vaginal secretions is an integral part of vulvovaginal care.

Acidity of vaginal secretions: Because the vagina communicates with the outside, its epithelium is colonized by bacteria. Its weakly acidic environment, mostly commonly in the pH 3.5-4.5 range, sometimes slightly higher in different, asymptomatic, ethnic populations (up to 4.7-5.0)14 15 16 (See pH Values below) protects from bacterial overgrowth that might lead to infection. Women need to understand that the degree of acidity is not corrosive like sulfuric acid (pH 1) and that pH is controlled by endogenous vaginal factors (estrogen and lactobacilli), not by diet, hydration, or the use of probiotics. Douching with vinegar produces transient change in pH and is never recommended because of its risks to the upper genital tract.

For any clinician evaluating women for vulvovaginal complaints, the use of vaginal pH and a microscope is essential. An understanding of basic microscopy is mandated for obstetricians and gynecologists by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and should be mandated for any clinicians who see patients with these complaints. (Principles of vaginal microscopy). Working without pH measurement and microscopy is the equivalent of working with one hand tied behind the back. Unfortunately, Hillier’s 2021 study showed that point-of-care tests including vaginal pH (15%), potassium hydroxide/whiff (21%), and wet mount microscopy (17%) were rarely performed. In their cross-referenced study, 47% received one or more inappropriate prescriptions, 34% were prescribed antibiotics and/or antifungals in the absence of bacterial vaginosis, tricomoniasis, or candidiasis, and return visits were more common for women treated empirically than for those not receiving treatment.17

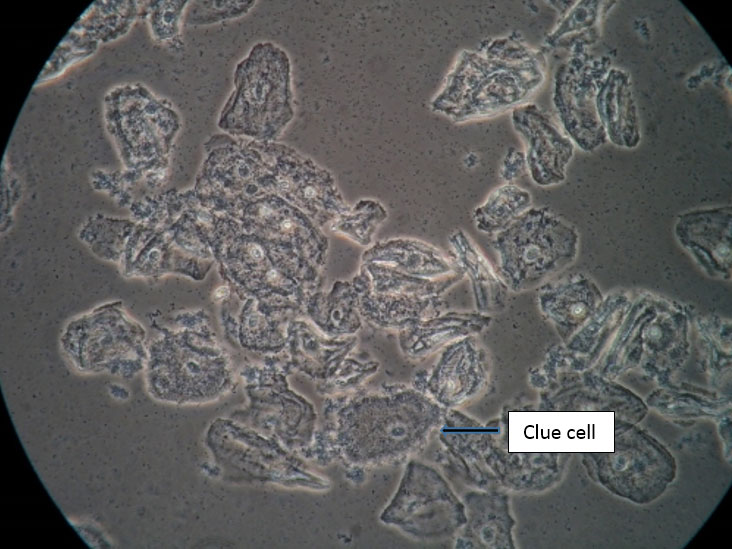

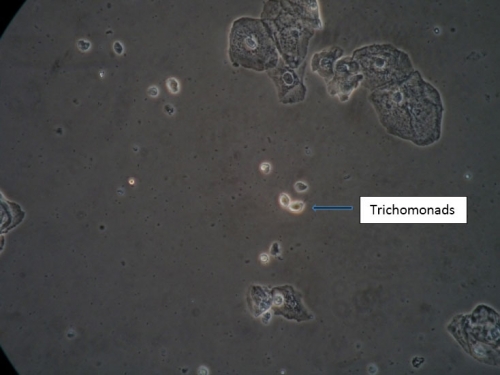

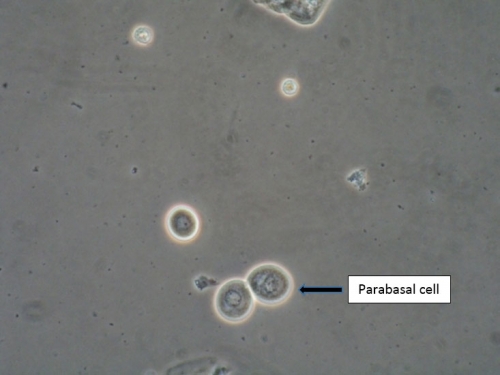

There is no substitute for the information obtained from a wet mount: not only the presence or absence of Candida, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomonads, but also the state of estrogenization as represented by the vaginal maturation index (VMI) in which vaginal pH is correlated with microscopic exam for mature versus intermediate squamous cells and immature parabasals,18 and inflammation represented the number of white cells and parabasal cells. Alterations in background flora, normally dominated by lactobacilli, complete the diagnostic picture. These findings, combined with vulvar findings on exam, allow the pattern recognition essential to determine a diagnosis. Cultures and nucleic acid probes supplement this information, but do not substitute for it.

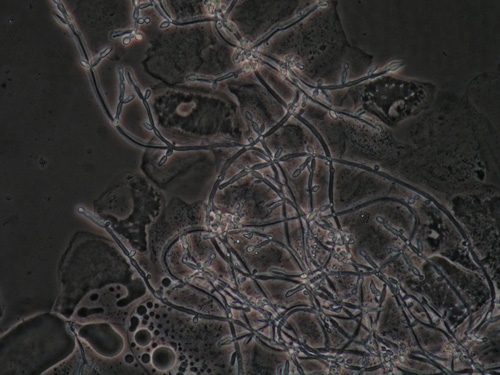

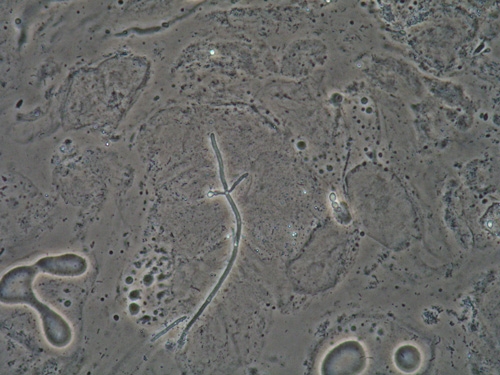

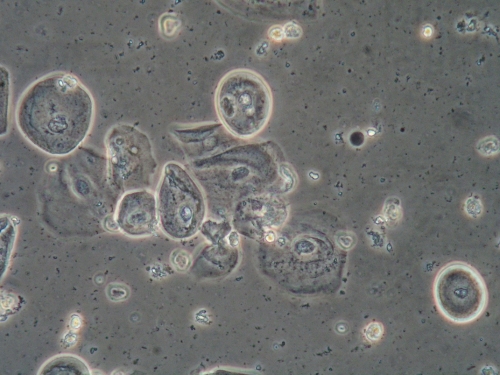

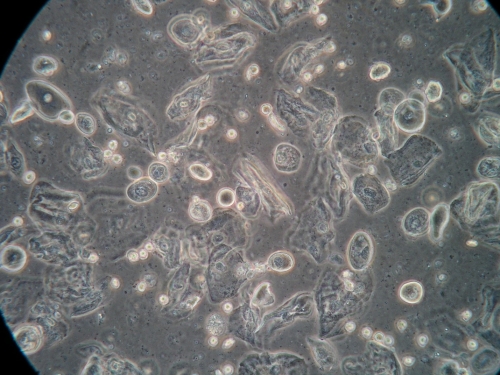

A light microscope, commonly found in physicians’ offices, is entirely adequate for diagnosis, (especially if a medical assistant can be designated to clean it on a regular basis). However, the use of a phase-contrast microscope is ideal because of the tremendous depth of detail that it supplies. Large and clear images facilitate identification of spores of Candida, the clue cells of bacterial vaginosis, and trichomonads. There is no other testing, other than a microscope, to identify vaginal inflammation through the recognition of parabasal cells from the vaginal wall epithelium. These may be present in active Candidiasis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV), and with vaginal atrophy associated with menopause and lactation. (See Genitourinary syndrome of menopause.) With phase-contrast microscopy, the clinician can distinguish lymphocytes from neutrophils by their nuclei. Background flora are also distinct, enabling the identification of the dominance of lactobacilli morphotypes in a normal vaginal sample (research laboratory testing is necessary for confirmation of individual lactobacillus species), or their diminution with disease.

A phase-contrast microscope is expensive, costing several thousand dollars. However, considering the millions of dollars spent annually on multiple pediatric, primary care, gynecology and specialty visits in search of correct diagnosis, and the recompense through increased accuracy and immediacy of diagnosis and treatment, the investment, in our consideration, is worth it. A less expensive phase attachment for a light microscope is also available.

Deterrents to use of pH and microscopy in the USA include regulations from the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA) regarding point of care testing. Adherence to the CLIA regulations involves some basic staff training. PH test strips must be dated and checked regularly, and all involved staff must complete simple, computer based annual testing for competency. There is a learning curve required to master microscopy, but the payoff in microscopic pattern matching enabling confident, immediate discussion of the patient’s condition makes the investment of time economical in the end. (Principles of microscopy)

An excellent video on wet mount is available through the Brookside Institute. www.operationalmedicine.org/ed2/Video/wet_mount_video.htm

Note: A clinician can do a wet mount in the time it takes a patient to dress after an examination.

New understanding of the diverse microbiota of the human vagina has exploded old ideas about definitions of “normal” vaginal pH and “normal” vaginal bacterial populations and is opening up a world of possibility in the search for treatment of vaginal infections. Advances in this understanding burgeoned with the 2008 National Institute of Health (NIH) global study called The Human Microbiome Project (HMP).19 Further studies on the human vaginal microbiome specifically have given depth to what we need to know to care for patients.20 21 22

Information on this very important and interesting field of research is found in Annotation O: The Vaginal Microbiome.

As seen in the section on the Vaginal Microbiome, the balance (composition and abundance) of vaginal microbes directly affects pH levels. In addition, pH depends on estrogen effects on vaginal secretions. Estrogen stimulates glycogen deposition on the surface of vaginal epithelial cells. Both the epithelial cells and the microbial enzymes degrade glycogen to glucose. Lactobacilli then metabolize the glucose to lactic acid, resulting in a vaginal pH generally around <4.5. As pointed out, (see Vaginal Microbiome) there are subtle differences in vaginal pH between different ethnic groups in the USA (White (pH 4.2±0.30), Asian (pH 4.4±0.59), Black (pH 4.7±1.04),Hispanic (pH 5.0±074)) and between and within countries.23

A pH measurement, as it stands alone, is a non-specific finding. Therefore, pH has to be evaluated within a context. The normal pH of non-contaminated vaginal secretions in females across the age spectrum is fairly predictable. The presence of estrogen and of lactic acid-producing Lactobacilli in normal flora produce consistent acidic (pH <4.5) results in healthy, non-lactating or postpartum women of reproductive age, with the caveat that some ethnic groups may demonstrate slightly elevated normal pH levels. pH is also predictably altered in conditions of imbalance of normal flora, hormonal changes (low estrogen), or infection and can, therefore, be used in the process of diagnosis. Contaminants, such as soaps, gels, lubricants, blood, semen, urine and even water, can alter the pH. Therefore, pH can never be used without full systematic exam and microscopy in seeking a diagnosis.

The acidity or alkalinity of the vaginal secretions should be tested with pH test strips that come in a box with a color scale. The test strip should be applied with a dry, cotton-tipped applicator (Q-tip) to the vaginal sidewall in the lower third of the vagina to avoid secretions from the cervix, which may have an elevated pH (a normal finding in the cervix). Alternatively, the dry Q-tip may be applied directly to the vaginal sidewall and then to the pH test strip itself to see the color change. Once the secretion sample is placed on the color test strip, any color changes can be compared with the scale on the box. With the strips that we currently use, the original color of the strip is light green. The expected “normal” color change is to yellow in the case of a pH of <4.5. The range of colors is from yellow to light green to darker green to blueish green to dark blue and the range of pH measured is from 4.0 to 7.0. The color change is stable for two to five minutes at room temperature.

In healthy, reproductive age women who are not lactating, the spot on the test strip should change from the light green base to yellow (pH 4.0-4.5), again with the caveat related to women of differing ethnicities. In healthy, postmenopausal women not using estrogen, the pH will usually be elevated. This may or may not be associated with discomfort, abnormal discharge, or dyspareunia. (Genitourinary syndrome of menopause). Women who are lactating have decreased estrogen levels and concomitant elevated pH and thinning of the vaginal walls. This effect is more pronounced early in the lactation period.

An advantage of doing a vaginal pH immediately upon insertion of the speculum (or with a Q-tip alone if the woman cannot tolerate a speculum) is that a low pH of 4.0-4.5 precludes most bothersome vaginal conditions (bacterial vaginosis, trichomonas, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, and atrophy). If you see a pH of 4.0-4.5, you can be reassuring to the woman right away. The only condition that will appear in an environment of any pH range is yeast. C. albicans actually prefers the low pH environment because of its positive association with estrogen. C. glabrata can grow in an environment with an elevated pH.

In most women, pH levels are directly correlated with the numbers of Lactobacilli found on wet prep, the next step in the diagnostic process (see wet mount below). Wet mount estimation of Lactobacilli, therefore, is a reliable indicator of vaginal pH.24 If a pH is elevated, crosschecking with the number of Lactobacilli seen can help to highlight contamination of the specimen versus the presence of pathology. (See wet mount below).

As stated above, the studies that show slightly elevated pH (to 5.0) in asymptomatic women of different ethnic groups also show different species of Lactobacilli being predominant. L. crispatus is more common in white and Asian groups, while L. invers is more dominant in black and Hispanic populations who are more likely to have normal pH values of 5.0. In addition, lactic acid-producing bacteria (some of them anaerobic) other than Lactobacilli may help to maintain the healthy vaginal ecosystem.25 Again, it appears that production of lactic acid is the key protective factor.

- Use cotton swab applicator to obtain secretions from the mid-portion of the vaginal sidewall.

- Avoid collecting the specimen from the cervix.

- Mix specimen with 0.5 cc saline suspension in test tube or paper cup.

- Saline should be fresh and at room temperature.

- Place a drop of the saline specimen on first slide.

- Place cover slip over specimen, avoiding air bubbles. Learn to avoid over-spill from your droplet which will soil the microscope lens.

- Perform microscopy within ten minutes.

- Add one drop of 10% KOH to another drop of saline mixture.

- Use a new slide or the other half of the first slide.

- Sniff for “fishy” amine odor that suggests BV or trichomonas.

- After the “whiff test,” place cover slip.

- Saline slide should be read first, then KOH.

Again, see the video resource by Michael Hughey, MD of Brookside Associates for learning how to perform the wet mount examination and whiff test. (Wet Mount)

- Put the slide on the stage.

- Rotate 10-x lens into place.

- Turn light on.

- Use coarse adjustment to focus.

- For contrast, lower condenser or adjust diaphragm to allow more or less light.

- Rotate 40-x lens into place.

- Increase light if necessary.

- Use fine adjustment knob to focus.

- Readjust diaphragm if necessary.

- Begin reading; review the entire slide.

- When using a phase contrast microscope, rotate to Phase III position to magnify.

- Vaginal Culture: Cultures for Candida or trichomonas (or rapid antigen and nucleic acid amplification tests), are indicated by clinical findings, or negative microscopy with clinical suspicion for these conditions. In one study, the sensitivity of microscopy for diagnosis of Candida and trichomoniasis was only 22 and 62 percent, respectively,26 and in another, microscopy failed to yield clear results 50% of the time, whatever the reason for that may be.27 Bacterial cultures of the vagina are not helpful and are rarely used by vulvovaginal experts. Vaginal bacterial cultures will always identify multiple strains of bacteria commonly found in and normal to the vagina, the skin, and the lower GI tract. Interpreting these as diagnostic of infection will lead to overuse of antibiotics and lack of efficacy of treatment. These do not need to be treated. This includes Group B Strep (GBS). This organism (GBS) is often recovered in non-pregnant patients, particularly in patients with desquamative vaginitis, but this laboratory finding neither establishes a diagnosis nor dictates treatment.28 The organism that provides key protection in the vaginal ecosystem is Lactobacillus.

- Cervical culture: Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis must always be considered in women with purulent vaginal discharge, fever, or lower abdominal pain. Any women with a history of high-risk behavior (new or multiple sexual partners), a symptomatic sexual partner, or an otherwise unexplained vaginal discharge that contains a high number of PMNs (polymorphonuclear leukocytes, more commonly called white blood cells) should be tested for the presence of these organisms. In addition, sexual behaviors that result in STI-related vulvovaginitis (e.g. trichomoniasis, herpes simplex virus) increase likelihood of coexisting STIs. The presence of high-risk behavior or any sexually transmitted disease requires screening for HIV, hepatitis B, and other STIs.

- Serologic tests: There are no serologic tests available for common causes of vaginitis. Serology, however, may be useful in the diagnosis of genital herpes, providing that evaluation be performed at least six weeks after the exposure. (Herpes simplex, the Atlas of Vulvar Disorders).

- Papanicolaou smear: The Pap test is an unreliable tool for diagnosing either bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis.29 30 When compared to Gram stain criteria for bacterial vaginosis, a Pap test has a sensitivity of 49% and specificity of 93%.31 In a symptomatic woman with bacterial vaginosis on a Pap test, a vaginal pH, amine test and wet mount should be performed; asymptomatic women do not need evaluation or treatment given that the diagnosis on Pap test is uncertain and it is unclear that asymptomatic, non-pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis benefit from treatment.32 For trichomoniasis, the Pap test has sensitivity similar to the wet mount but yields a false-positive rate of at least 8% with standard tests and 4% with liquid based cytology; thus, a diagnosis based on cytology can lead to an inaccurate diagnosis of a sexually transmitted infection. When feasible, in patients with trichomonas found on a Pap test, a wet mount and, if negative, a culture or one of the more sensitive nucelic acid amplification tests (NAATs) should be performed. If culture or NAAT is unavailable, the least expensive approach is to treat the patient with metronidazole. In populations with a low prevalence of trichomoniasis (5% or less), this approach may lead to an unnecessary treatment in more than 50% of cases. Optimal evaluation of the vagina includes pH, wet mount, and yeast culture done on several occasions since a single evaluation is inadequate to evaluate the dynamics of the vagina.

Other tests in the absence of the microscope: At times, patients must be evaluated without microscopy. In these cases, history, examination, and yeast culture for Candida are available. Elevated vaginal pH determines which patients need further testing for bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. Point of care tests for trichomonas using DNA probe, (OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test) or RNA probe (BD-Affirm), are available. Point of care tests for pH and amines (QuickVue Advance pH and Amines Test), G. vaginalis proline iminopeptidase activity (QuickVue Advance G. vaginalis test), and vaginal sialidases (OSOM BVBlue test), as well as RNA probe for Gardnerella (Affirm VP III) and PCR assays (BD Max Optima Panel and Aptima BV), as well as other laboratory-specific tests are FDA approved to aid in the diagnosis of BV. They are expensive and do not provide the information about inflammatory white blood cells and immature epithelial cells (parabasal cells) that come with microscopy.

The word “vaginitis” represents a spectrum of conditions that cause itching, burning, irritation, sometimes pain, abnormal discharge, and malodor.33 In the United States, the most common causes are bacterial vaginosis (22-50% of symptomatic women), vulvovaginal candidiasis (17-39%), and trichomoniasis (4-35%).34 Another 7-72% of women with vaginitis may remain undiagnosed,35 with symptoms caused by multiple other conditions: genitourinary syndrome of menopause (atrophy), desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, drug reactions, lichen planus, or vulvodynia. See Table P-6 below.

Vulvovaginal candidosis (VVC) (yeast vaginitis, Candida vulvovaginitis, candidiasis)

Introduction

VVC is defined as signs and symptoms of vulvovaginal inflammation in the presence of Candida species.36 Recurrent VVC (RVVC) is commonly defined as three or more proven cases in 12 months or at least three episodes unrelated to antibiotic use that occur within one year.37 Chronic VVC is defined as unremitting vulvovaginal inflammation causally associated with Candida.38

In 2016, the genome of Candida was sequenced, giving better information on the species’ features; but details of the intricate mechanism leading from colonization to infection are still not fully elucidated, and RVVC is not fully understood. One of the greatest hopes for further information from the genome is the development of truly fungicidal anti-fungal medications. Most currently available anti-fungals are fungistatic, decreasing the fungal load, but reliant on the vaginal host inflammatory reaction to clear up the infection. However, the recent development of “fungerp” triterpenoid medications which target fungal cell walls43 and novel azole medications which inhibit synthesis of fungal cell membranes and have very long half lives44 offer the promise of fungicidal action and greater clinical efficacy in the future. In addition, vaccines targeting various components of the fungal cell wall and elements essential for attachment and tissue invasion by Candida organisms are currently in early stages of development. The large variation in and plasticity of Candida species, and the body’s immune tolerance toward commensal fungi make this work challenging.45 Non-Candida albicans species are emerging pathogens and can also asymptomatically colonize human mucocutaneous surfaces, or produce symptomatic vaginitis or recurrent symptomatic vaginitis.46 See non-albicans Candida below.

Epidemiology of VVC

VVC is not a reportable disease, and therefore, the information on its incidence is incomplete and based on epidemiology studies that are often hampered by inaccuracies of diagnosis and/or the use of non-representative populations.47 Most, if not all women carry Candida in the vagina at some point of their lives, yet sometimes without symptoms of infection.48 Identification of vulvovaginal Candida is not necessarily indicative of disease since the definition of VVC requires both signs and symptoms of vulvovaginal inflammation in the presence of Candida species. But, in 70–75% of women, a diagnosis of VVC is made at least once during their childbearing years.49 It is estimated that 50% of initially infected women will suffer a second VVC event and 5–10% of all women will develop RVVC.50

The incidence of VVC in symptomatic women varies depending on the location in the world, as well as the populations studied.51 The highest incidences of Candida are reported by epidemiological studies made in African countries such as Nigeria,52 followed by Brazil53 then Australia.54

The lowest incidences are reported in the European countries of Greece (12.1%)55 and Italy (19.5%).56 In India, incidence of Candida ranges from 17.7 to 20.4%.57 58 59 Candida glabrata has been reported as the dominant species in studies from several African and Asian countries including Nigeria, Ghana, Turkey, India, and Lebanon.60 All of these epidemiological studies reported a higher incidence of VVC in women at reproductive age (20–40 years) than in women at menopause or in pre-pubertal girls.

Microbiology

There are more than 350 different species of Candida in nature. At least 13 Candida species cause infection in women. C. albicans is the most common.61

Other species of Candida are denoted as “non-albicans Candida,” with Candida glabrata the most common, C. tropicalis in second place, followed by C. parapsilosis and C. krusei. Culture is required to identify the species when Candida is recurrent or refractory.

Typically, a single species is identified, but two or more species have been found in 1-10% of women with VVC.62 63 64 Most of these mixed infections are caused by an association between C. albicans and C. glabrata.65 66 67

Historically, 85–95% of Candida species identified in women with VVC were C. albicans.68 69 However, there are studies published during the 1990’s reporting an incidence of C. albicans below 85% and in some countries even below 50%. It has been suggested that the widespread and inappropriate use of anti-fungal treatments (self-medication and prolonged anti-fungal therapy) may lead to the selection of non-albicans species (such as C. glabrata), which are more resistant to the commonly used anti-fungal agents than is C. albicans.70 71

Lactobacilli may be protective through competition with Candida for nutrients, stearic interference with Candida adherence, and elaboration of hydrogen peroxide and inhibitory bacteriocins.72 Production of biosurfactants by lactobacillus species can prevent fungal adhesion to epithelial walls. Lactobacillus production of organic acids such as lactate and bacteriocins exert fungistatic effects. Saturation of epithelial adhesion sites and co-aggregation (adherence of vaginal bacteria to fungal organisms) by Lactobacillus species can prevent Candida adherence to epithelial walls. Lactobacilli can also reduce the expression of genes in Candida responsible for yeast adherence and hyphal formation. And, lactobacillus species alter the host immune response to attract granulocytes and promote host immune defense.73 However, at the present time, treatment with lactobacilli has not been effective in preventing antibiotic-related Candida.

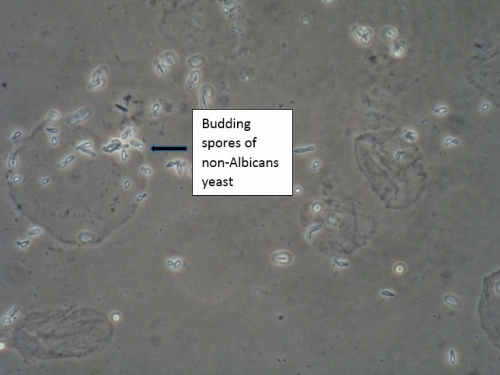

Non-albicans Candida

Culture proven non-albicans Candida found in the vagina represents another challenge. Like Candida albicans, non-albicans Candida may be present, (although less commonly) as a commensal not responsible for perplexing vulvovaginal symptoms. It can also be the cause of isolated symptomatic vaginitis or recurrent symptomatic vaginitis, or act as a source of secondary infection in women with an epithelial disorder or with contact irritant use. Non-albicans yeast, most commonly C. glabrata, may be responsible for up to 33% of recurrent cases of candidosis.74 In fact, non-albicans species have been more commonly isolated among patients with RVVC than in women with sporadic VVC,75 possibly, as mentioned above, due to a higher anti-fungal exposure and widespread use of over the counter anti-mycotics among patients with RVVC.76

High percentages of non-albicans species causing VVC, mainly C. glabrata, have been also associated with increasing age,77 78 patients with uncontrolled diabetes,79 and HIV-infected women.80 These associations may occur from changes in patient physiology, estrogen balance, and decrease in immune functions.81

C. glabrata is predominantly found in northern Europe, the United States and Canada. C. krusei is seen more commonly in older white women. C. parapsilosis (Southern Europe, Asia and South America) is more common in transplant recipients and low birth weight infants. T. tropicalis (Asia-Pacific) occurs more commonly in association with pregnancy, neutropenia, and malignancy. C. dubliniensis is phenotypically similar to C. albicans, and may test as albicans. It is commonly found in HIV positive persons. C. auris is an emerging non-albicans species first seen in Japan in 2009 but currently spreading rapidly over multiple countries. Concerningly, this organism is difficult to diagnose by standard laboratory methods and has developed multi-drug resistance.82 83

Vaginitis caused by non-albicans species is clinically indistinguishable from that caused by C. albicans although signs and symptoms may be milder in some non-albicans candida infections.84 The use of non-azole anti-fungals, such as boric acid and flucytosine, has been shown to be effective in treating VVC caused by non-albicans species, especially C. glabrata,85 which demonstrates intrinsically low susceptibility to the azoles and the ability to develop high resistance to them.86

Pathogenesis of Candida

Access of Candida to the vagina

Candida gains entry to the vagina by crossing from the rectum over the perineum,87 but it has long been known that decreasing gastrointestinal carriage of Candida by oral administration of nystatin does not prevent recurrent symptomatic vaginal infection.88 A systematic review from an interdisciplinary and environmental medical point of view has been undertaken and failed to draw conclusions about the patho-genetic significance of intestinal Candida colonization.89

Candida infection may arise (less commonly) after sexual contact,90 or from relapse or persistence of the organism after previous Candida infection.

Colonization

In the vagina, Candida may live in harmony as a colonizer next to vaginal bacteria. The natural history of asymptomatic vaginal yeast carriage is unknown, but may exist for months or years.91

Vertical transmission from mother to infant during childbirth allows for early establishment of colonization of the oral cavity and the rectum with Candida, where its interaction with other resident microbiota and host immunity prevent transition from commensal organisms to pathogens. Extragenital colonization has been implicated as a reservoir of genital recolonization in patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.92 At the vaginal level, epithelial cells under the influence of reproductive hormones93 provide a mechanical barrier, recognize and process antigens, secrete immune mediators and orchestrate the vaginal immune system in a delicate balance of protection against pathogens while allowing the immune tolerance necessary to accept semen and a developing fetus.94

Symptomatic candidal vaginitis (VVC)

Besides colonization, Candida has the ability to cause symptomatic vaginitis by transformation to an invasive pathogen. Candida may exist as a spore or a filament (hyphae or pseudohyphae). All forms are thought to play a role in the progression of vaginal infection in women.95 Transformation from colonization to infection involves a complex interaction of:

(1) host inflammatory responses (discussed below)

(2) Candida virulence factors.96 While it is usually assumed that the transition from asymptomatic colonization to symptomatic candidiasis occurs following a perturbation or loss of local defense mechanisms, this transition may also occur because of factors that enhance fungus virulence.97 These include:

- Morphologic plasticity: albicans is a polymorphic fungus that can reversibly transition between yeast, pseudohyphal and hyphal forms. The unicellular yeast form is commonly regarded as a harmless colonizer, but transition to the hyphal form allows the organism to adhere to and invade epithelial cells, resulting in extensive host cell damage. Host membranes are weakened by degradative enzymes secreted at the hyphal tip and pressure exerted by the elongating filament is then sufficient to penetrate the host cell.

- Phenotypic plasticity: albicans has the capacity to switch from a white phenotype producing smooth white colonies to gray and opaque phases which are less virulent. This switching between white and opaque phenotypes helps C. albicans evade host immune responses, as opaque cells are less susceptible to phagocytosis by macrophages and are able to evade killing by neutrophils.

- Genomic plasticity: albicans is capable of gross chromosomal rearrangement, aneuploidy, and loss of heterozygosity when exposed to different stresses. This allows the organism to adapt to a changing environment by changing the number of specific genes on a given chromosome. For example, amplification of two resistance genes on the left arm of chromosome 5 (ERG11 and TAC1) is associated with azole resistance.98

- Fungal products: albicans possesses multiple redundant pathogenic mechanisms for triggering inflammatory processes within the host. Candida virulence factors are genetically controlled, including an estradiol binding protein (EBP),99 multiple mechanisms for adherence of Candida to the epithelial cell prior to invasion, as well as ability for hyphal and biofilm formation.100 In addition, extracellular proteinases of C. albicans trigger immune responses locally and systemically.101 C.albicans has the ability to modulate phagocytosis by host neutrophils and macrophages, and endocytosis of C. albicans into epithelial cells both contributes to its invasiveness and stimulates phagocytic cells to produce inflammatory cytokines. In the non-albicans candida species, C. glabrata has highly efficient adhesion to various surfaces due to a range of adhesins, high stress resistance, and the shortest replication time of all Candida species. C. glabrata strains have an intrinsic resistance to azole antifungal medications, and mixed biofilms consisting of C. glabrata and C. albicans lead to more robust and complex structures and improve antifungal resistance.102.

- Drug resistance mechanisms: One of the main routes of resistance is the over-expression of efflux pump-related genes that results in decreased drug concentration within fungal cells (MDR1 genes in fluconazole resistance, and CDR1/CDR2 genes in resistance to all azoles). Overexpression of the ERG genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis and biofilm formation also results in drug resistance among Candidal species.103

Since many Candida infections occur without a clear risk factor,104 it appears that focus on host inflammatory risk factors and Candida virulence factors is important.

At this time, new therapies are not available to address immune factors, but it is helpful to discuss with affected women that immune factors related to both the Candida organism and the vagina may cause their complex problems.

Recurrent vulvovaginal Candida (RVVC)

RVVC is usually defined as idiopathic, with no known predisposing factors, affecting up to 5% of all women who have a primary sporadic episode of VVC.105 106 Anti-fungal therapy is highly effective for isolated symptomatic infection but does not prevent recurrences. In fact, maintenance therapy with the efficacious anti-Candida drug fluconazole lengthens the time to recurrence but does not provide a long-term cure.107 There is now concern that repeated treatments might induce drug resistance,108 and result in an increased incidence of non-C. albicans, intrinsically resistant, species.109 110 111

Drug resistant Candida species have been a growing trend for the past decade, and multi-drug resistant Candida species are now being reported all over the world.112 Most non-albicans Candida species now have higher MIC’s (minimal inhibitory concentrations) for both prescribed and over the counter antifungal agents. Resistance is now common in non-albicans Candida species to the azole group of antifungal agents, and increased dose-dependent resistance is reported. In addition, organisms from patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis are more resistant to azole medications than those from uncomplicated vulvovaginal candida patients. 113

The pathogenesis of RVVC remains unknown. Many experts believe that RVVC results from relapse: DNA typing studies suggest that persistent Candida in the vagina from a previous infection invades again.114 The DNA of strains of Candida isolated from vaginal cultures of women before and after treatment for yeast vaginitis showed that 86% of the strains were identical.115 Some organisms persist within the vaginal vault, generally in numbers too small to be detected by conventional vaginal cultures, re-emerging to cause infection weeks or months later. Despite a 1993 report of a systemic immune deficit,116 there is now evidence that patients with RVVC are systemically immunocompetent. A local anti-Candida immune dysfunction in these subjects is suspected;117 for some forms of recurrences, the source could be genetic.118 119

A different perspective on Candidiasis turns away from the emphasis often focused on the estimated 5% of women with RVVC and the lack of demonstrated immune dysfunctions in these women. Instead, the focus might be on the 95% of women who, even after a first acute VVC attack, do not develop RVVC. These women may be colonized, but they remain largely disease-free for the rest of their lives, with only occasional, limited, and perfectly curable episodes during pregnancy or following some antibiotic therapy. This occurs despite more-than-frequent exposure to Candida and colonization from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, suggesting that specific immunity may be induced by the initial, even sub-clinical episodes; this immunity may be boosted by commensalism and effectively prevents the onset of chronic infection.

Proponents of this perspective speculate that what is probably required for avoiding disease is control of the virulence traits of the fungus, which may allow the transition from commensal status to pathogenic status. Control of Candida virulence may be better achieved by mobilization of host immune responses through a vaccine.120 Multiple potential fungal targets for vaccine development have been explored between 1986 and the present, and two recombinant protein vaccines have progressed to Phase 1b and Phase 2a clinical trials (Schmidt et al 2012, and DeBernardis et al 2012). However, despite significant advances in immune and vaccine biology over time, a viable commercialized vaccine against fungal infections has yet to make it to market.121

Host inflammatory response factors

The host’s immune response is a crucial element of pathogenesis and host pathogen interaction.122 The immune system is separated into two branches: humoral immunity, for which the protective function of immunization arises from antibodies, complement proteins, and certain antimicrobial peptides located in the cell-free bodily fluid or serum (humor), and cellular immunity, for which the protective function of immunization is associated with cells: phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and sometimes, the release of various cytokines in response to an antigen. It is established that cell wall constituents of Candida species have antigenic properties that can evoke both humoral and cellular host immune responses during the course of infection.

The mucosa of the female reproductive tract, with its tissue architecture, cervicovaginal secretions, and fluid, has been shown to contain humoral and cellular constituents of innate immunity, together with cell populations required for initiating, recruiting, and maintaining an efficient adaptive immune response.123

Cell mediated immune response

The cell-mediated immune response is clearly important in the host defense against Candida, as reflected by the higher prevalence of infections among individuals whose cellular immune systems are impaired. As discussed above, an early hypothesis was that the systemic cell-mediated immunity of the host was defective, but current consensus today is that women with RVVC have a local vaginal immune deficiency.124 This local immune deficiency has yet to be clearly defined.

The exact mechanisms of induction of cell-mediated immunity in VVC and RVVC have not yet been elucidated. T cells can be identified in large numbers in the human vagina. Their characteristics suggest migration to the vaginal epithelium in response to local antigenic stimuli and/or inflammatory chemokines.125 126

Neutrophils may also be implicated in host defense against Candida infection. Studies have shown that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) increased neutrophil-mediated damage to pseudohyphae of C. albicans, perhaps in association with IFN-gamma.127 128 Yeast hyphal formation and expression of ECE1 which encodes for the hypha-expressed toxin candidalysin are the crucial virulence determinants driving neutrophil recruitment.129

Humoral immune response

The role of the humoral immune response in preventing disease progression during Candida infection has been unclear and controversial.130 131 Some of the host immune response to candidal infection may be modulated by elements of the vaginal microbiome. L. crispatus, one of the dominant members of the vaginal microbiome, can diminish C. albicans virulence and enhance local immune response of vaginal epithelial cells by modulating the immune cytokines and chemokines profile, i.e. upregulating IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, and downregulating IL-8. Lactobacilli can also inhibit biofilm formation by C. albicans. Also, low pH and bactericidal compounds secreted by Lactobacilli tend to suppress Candida overgrowth and its transition from a virulent yeast form to virulent hyphal form. Surfactant protein A, produced in the vaginal mucosa, provides host defense by opsonizing pathogens, altering levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, stimulating oxidative burst by phagocytic cells and promoting differentiation of antigen presenting cells, thereby linking innate with adaptive immunity.132

However, work with polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies, as well as mannan-specific IgG antibodies which trigger both the classical and alternative complement pathways, 133 suggests that development of a vaccine or short-term protective antibodies may be feasible. Indeed, in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice, a vaccine against C. albicans conferred reduced fungal burden and improved survival.134

Host risk factors for Candida

Pregnancy and estrogen

Human Candidal vaginal infections occur almost exclusively during the reproductive years and are extremely rare in premenarchal and postmenopausal women.135 The prevalence and severity increase in the premenstrual week.136 It is well established that Candida vaginitis is more often seen in pregnant than in non-pregnant woman.137 Recurrence is more common and therapeutic response is reduced in pregnancy. Increased vaginal glycogen associated with high levels of reproductive hormones, becomes a carbon source for Candida. It is well known that estrogen increases adherence of yeast to vaginal cells, promoting germ tube formation, and that Candida possesses a cytosol binding system for estrogen.138 It is possible for a woman to be yeast free until the commencement of hormone replacement therapy at menopause.

Diabetes mellitus

Uncontrolled diabetes predisposes to yeast vaginitis, but candidiasis is not increased when the disease is well controlled.139 In glucose tolerance tests on women with recurrent candidiasis, there was no increased frequency of abnormal test results compatible with diabetes or pre-diabetes. Plasma glucose values were within the normal range, but were substantially higher than controls, suggesting that a diet high in refined sugars could contribute to the risk of candidiasis.140 Clear support for elimination of all carbohydrates does not exist in medical evidence. Women with type 2 diabetes appear prone to colonization and infection by non-albicans Candida species. Elevated plasma glucose levels and subsequent glucosuria induce proteins in Candida which favor yeast adherence. Treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors may increase the risk for vulvovaginal candidiasis.141

Antibiotics

Estimates of the frequency of candidosis following antibiotic use ranges from 28% to 33%,142 thus, most women who receive antibiotics do not develop candidiasis. All antimicrobials are thought to cause candidosis by eliminating the protective bacterial flora, allowing overgrowth of Candida in the gastrointestinal tract, vagina, or both.143 Low numbers of lactobacilli have been found in vaginal cultures from some women with Candida vaginitis.144 But administration of lactobacillus (oral or vaginal) during and for four days after antibiotic therapy does not prevent post-antibiotic vulvovaginitis.145

Gastrointestinal tract

Although oral nystatin does not prevent vaginal Candida infections,146 there may be a link between symptomatic vaginal Candida infections and the gastrointestinal tract. In a study of both HIV infected and non-infected women, bowel movements appeared to correlate with fungal growth, as diarrhea was associated with an increase in vaginal fungal growth. Women who had diarrhea in the past 30 days were approximately twice as likely to have fungal growth than those who did not have diarrhea, which reached statistical significance in both groups.147

Immunosuppressive medications and disease

Use of corticosteroids is likely to be associated with recurrent Candida because of local suppression of immunity.148 Candida infections are also more common with use of immunosuppressive drugs, and with HIV infection.149

The long term administration of fluconazole in HIV positive individuals for prophylaxis against other fungal opportunistic infections has resulted in an increased prevalence of non-albicans Candida species in this population.150

Behavioral factors

Contraceptives

Contradictory results reported from different studies make the relationship between the OCP and Candida a controversial topic. Increased yeast colonization is reported in users of intrauterine contraceptive devices, sponges and diaphragms, and condoms, with and without spermicides.151 An extensive study of college students did not show an increase in the risk of symptomatic vulvovaginal candidosis in users of oral contraceptives, diaphragms, condoms, or spermicides.152

At least two studies have suggested that recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis in IUD user may be related to the ability of some species to attach to the IUD and form a biofilm rather than related to the IUD itself. Spermicides are not associated with Candida infection.153.

Sexual activity

Women who are not sexually active often develop vulvovaginal candidiasis; the incidence of the disease increases dramatically in the second decade of life, with the onset of sexual activity.154 Candida occurrence declines in women older than 40 years, but can resurface with use of estrogen after menopause.

The theory that recurrences are caused by re-infection of the woman by her male sexual partner has been suggested repeatedly, with some data suggesting that sexual transmission does occur.155 Candida species may be harbored in the male gastrointestinal tract, semen, urine, and oral cavity.156 Male colonization is associated with vaginal colonization, often with the same strain.157Reed et al158 studied sexual behaviors that were associated with recurrences of C. Albicans vulvovaginitis. Vaginitis was found to be unrelated to the presence of Candida in various body sites of the female or her male partner prior to the recurrence. Even Candida carriage in the vagina failed to predict subsequent symptomatic Candida vulvovaginitis. The following sexual risk factors for recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis were, however, identified: the female masturbating with saliva or cunnilingus from her partner, and the male masturbating with saliva or having had a younger age at first intercourse (reason unclear). They also found evidence that frequency/periodicity of sexual intercourse is associated with acute Candidal vaginitis frequency. Receptive oro-genital sexual intercourse consistently emerges as a risk factor for Candida.159 It is not clear whether this is related to transmission of the organism. Treatment of partners is not recommended unless they have symptoms.160 Occasionally, male partners of asymptomatic female carriers of Candida develop transient post-coital penile erythema and pruritus, suggesting inflammation from a hypersensitivity reaction. Women who exclusively have sex with women do not appear to have an increased risk of vulvovaginal infection.161

Other factors

Chemical contact, atopy, local allergy, or hypersensitivity reactions could alter the vaginal milieu and facilitate transformation from asymptomatic colonization to symptomatic vaginitis.162 Evidence is weak and conflicting regarding risk from sanitary pads and tight-fitting clothing.163

Both vaginal colonization and transition to infection have been linked to certain host genetic factors, including mannose-binding lectin polymorphisms, ABO-Lewis non-secretory blood group phenotype, and Y238X polymorphism in the Dectin-1 gene.164

Clinical manifestations

The clinical spectrum of symptomatic vaginitis varies from an acute, exuberant, exudative form with copious, white, vaginal discharge with little to no odor, and large numbers of germinated yeast cells, to the absence of discharge, fewer organisms, but the same severe pruritus. Clinical signs and symptoms in infections caused by different Candida species are a source of debate; C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis tend to be associated with milder, often absent symptoms.165 Vulvar pruritus is the dominant feature of candidal vulvovaginitis. Women may also complain of dysuria (typically perceived to be external or vulvar rather than urethral), soreness, irritation, and dyspareunia. There is often little or no discharge; but the typical white and clumpy (curd-like) secretions may be seen. Symptoms are often worse in the week prior to menses.

However, the secretions may also be thin and loose, indistinguishable from the discharge of other types of vaginitis.

Diagnosis of Candida by simple inspection of vaginal secretions is not possible. Some patients, primarily those with C. glabrata infection, have little discharge and often only erythema on vaginal examination.166 Evidence of excoriation may be present. Candida albicans is also a frequent cause of vulvar fissuring.

Diagnosis of Candida

Reliable diagnosis of Candida cannot be made on history and physical examination alone. Diagnosis requires:

- visualization of blastospores or pseudohyphae on saline or 10% KOH microscopy or

- a positive culture in a symptomatic woman. A culture is of no value if the woman has recently used anti-fungal treatment. Repeating the culture if a woman continues to be symptomatic after treatment is important. Some experts do not recommend yeast cultures if microscopy is negative. On the other hand, microscopy skills vary widely, artifacts (hair and fibers, overlapping cells) abound, and the cost of culture has come down. A negative culture in the presence of vulvovaginal symptoms educates the woman that Candida albicans is not the reason for her discomfort, and encourages the clinician to look for other explanations.

In addition to vaginal yeast culture, there are a number of newer diagnostic technologies on the market. They vary in sensitivity, specificity, which species of Candida are tested for and reported, and availability in different health care settings. These point-of-care tests are considerably more expensive than in-office microscopy, but may be helpful in the setting of recurrent symptoms or low fungal loads.167

- DNA Probes:

-

-

- Affirm VP III (BD): Probe for Candida, Gardnerella, and Trichomonas. 58% sensitive, 100% specific. Detects “Candida species” without reporting individual speciation.

-

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Assays:

-

-

- BD Max Vaginitis Panel (BD): 90.7% sensitive, 93.6% specific. Detects Candida Group (C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. dubliniensis), C. glabrata, and C. krusei. FDA cleared.

- SureSwab Candidiasis (Quest Diagnostics)

-

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs):

-

- NuSwab (LabCorp): 97.7% sensitive, 93.2% specific. Detects C. albicans and C. glabrata.

- SureSwab Advanced Candida Vaginitis (CV), TMA (Quest Diagnostics): Employs transcription mediated amplification (TMA). Reports C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. dubliniensis, and C. glabrata.

In addition, there is an emerging market for at-home testing for vaginitis. These tests range from simple pH testing for bacterial vaginosis, to immunoassays and NAATs which test for Candida and other vaginal and cervical pathogens. Some platforms report results at the point of testing, and some need to be sent out and will report results within 2 to 5 days. There is currently little to nothing in the medical literature evaluating the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of these tests, and their cost can be substantial, but some of them offer the convenience and privacy of home self-collection.

Pap smear is positive in 25 percent of patients with culture positive, symptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis. 168 But since the cells evaluated on a Pap smear are from the cervix, and are not affected by Candida vaginitis, the Pap smear is not a sensitive test.169 If Candida is found on a Pap smear of an asymptomatic woman, treatment is not required.

Most women with RVVC are HIV negative. Only women with RVVC who have risk factors for HIV infection should be tested.170

It is well established that self-diagnosis is frequently inaccurate.171 In a study that administered a questionnaire to 600 women to assess their knowledge of the symptoms and signs of vulvovaginal candidiasis (and other infections) after reading classic case scenarios, only 11 percent of women without a previous diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis correctly diagnosed this infection. Women who had had a prior episode were more often correct (35%) but were likely to use over-the-counter drugs inappropriately to treat other, potentially more serious, gynecologic disorders. In another report, the actual diagnoses in 95 women who self-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis were: vulvovaginal candidiasis (34%), bacterial vaginosis (19%), mixed vaginitis (21%), normal flora (14%) Trichomonas vaginitis (2%), and other (11%). Women with a previous episode of vulvovaginitis candidiasis and those who read the package insert for their over-the-counter medication were not more accurate in making a diagnosis than other women.172.

Diagnosis may be confounded when co-existent causes of symptoms (itching e.g.) are present, such as non-albicans Candida and a skin disorder, or Candida and vulvodynia. Consideration of the multiple other sources of vulvovaginal irritation prior to treatment of the culture positive Candida is important. (Consult Table P-6). Confirm whether the vulvovaginal epithelium appears quiet or inflamed. Lack of erythema or lesions suggests that inflammation from yeast is not present. Conversely, presence of erythema and/or alterations in skin texture or integrity may be signs of either Candida or a vulvar skin condition, irritant use, or other conditions, as listed in the table. Loss of vaginal architecture requires consideration of lichen sclerosus and/or biopsy.

Many vulvovaginal experts do not treat a positive culture for non-albicans Candida unless they are convinced that symptoms arise from the Candida and not another source. Watching and waiting, after explanation to the patient that the non-albicans yeast may be an innocent bystander, may show that symptoms are not significant and culture stays positive in a patient whose irritative symptoms do not add up to a diagnosis of Candida vulvovaginitis. It is possible that the patient has vulvodynia with irritative symptoms suggesting yeast if they have been present repeatedly over time when cultures have been negative. If the conditions in Table P-6 are eliminated, vulvodynia is the diagnosis.

Over a twenty five years ago, Candida albicans was classified as uncomplicated or complicated.173 The classification has been accepted internationally.174

Table P-5: Uncomplicated and complicated Candidiasis (Candidosis/Candida vulvovaginitis)175

| Uncomplicated candida vulvovaginitis | Complicated candida vulvovaginitis |

|---|---|

| Sporadic or infrequent episodes | Recurrent episodes (three or more per year) |

| Mild to moderate symptoms or findings | Severe symptoms or findings |

| Suspected Candida albicans infection | Suspected or proved non-albicans Candida infection |

| Non-pregnant women without medical complications | Women with diabetes, severe medical illness, immunosuppression, pregnancy, other vulvovaginal conditions |

Differential diagnosis

As discussed under Diagnosis, many women presenting with irritative vulvovaginal complaints are initially treated for Candida. Table P-6 shows the lengthy differential for pruritic and irritative vulvovaginal complaints. It is also important to recognize that Candida can occur concomitant with, or as a secondary infection with many of these conditions.

Table P-6: Differential diagnosis of irritative vulvar symptoms

| vaginitis (Candida albicans, non-Candida, BV, trichomoniasis) |

| sexually transmitted infections |

| desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) |

| contact irritants, allergens |

| seminal plasma allergy |

| loss of estrogen at any age after puberty |

| vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) |

| dermatitis (eczema), dermatosis |

| lesions, ulcers, erosions, fissures, papules, pustules |

| systemic disease, e.g. Sjögren, Crohn |

| drug reaction |

| pain syndromes and hyperpathic itching |

| squamous cell carcinoma |

Treatment of uncomplicated candida vulvovaginitis

Treatment of uncomplicated candida vulvovaginitis can be any oral or vaginal azole. There are no significant differences in efficacy among topical and systemic azoles (cure rates >80 percent for uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis).176 There are, however differences in the base ingredients. Miconazole, terconazole and butoconazole all contain propylene glycol to which many women are sensitive. They will tell you they had an “allergic” reaction to one of these topical drugs, meaning they had immediate contact irritation with redness and burning. Clotrimazole has no propylene glycol and is less likely to cause irritation. It is our preferred topical azole choice.

A single dose of fluconazole 150 mg orally is effective and usually preferred by women to the topical treatments, although it may take up to 48 hours before symptoms abate. Fluconazole interacts with some other drugs so careful review of medications being taken should be reviewed.177 178 In addition, in a nationwide cohort study in Denmark, use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of spontaneous abortion compared with risk among unexposed women and women with topical azole exposure in pregnancy. Please see the Pregnancy section under Treatment for further information regarding use of fluconazole in pregnancy.

In women susceptible to symptomatic yeast infections with antibiotic therapy, a dose of fluconazole (150 mg orally) at the start and end of antibiotic therapy may prevent post-antibiotic vulvovaginitis.

Uncomplicated infections usually respond to treatment within a couple of days. There is no medical contraindication to sexual intercourse during treatment, but it may be uncomfortable until inflammation improves. Treatment of sexual partners is not indicated.180.

Table P-7: Treatment for uncomplicated Candidiasis (Candidosis/Candida vulvovaginitis) (*= most frequently used regimen)

| Intravaginal agents for uncomplicated Candida vulvovaginitis | Oral agents for uncomplicated Candida vulvovaginitis |

| Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally for 3 days* | Fluconazole 150 mg oral tablet, one tablet in single dose (avoid in pregnancy) |

| Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g (Butaconazole1-sustained release), single intravaginal application | Ibrexafungerp two 150 mg tablets (300 mg) taken twice, 12 hours apart (600 mg total) |

| Clotrimazole 1% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7–14 days* | |

| Clotrimazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 3 days | |

| Clotrimazole 100 mg vaginal tablet for 7 days | |

| Clotrimazole 100 mg vaginal tablet, two tablets for 3 days | |

| Miconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7 days* | |

| Miconazole 4% cream 5 grams intravaginally daily for 3 days | |

| Miconazole 100 mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for 7 days* | |

| Miconazole 200 mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for 3 days* | |

| Miconazole 1,200 mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for 1 day* | |

| Nystatin 100,000-unit vaginal tablet, one tablet for 14 days | |

| Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally in a single application* | |

| Terconazole 0.4% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7 days | |

| Terconazole 0.8% cream 5 g intravaginally for 3 days | |

| Terconazole 80 mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for 3 days |

Treatment of complicated candida vulvovaginitis

Women with severe inflammation or factors associated with complicated Candida vulvovaginitis are unlikely to respond to short courses of topical anti-fungal drugs or a single dose of fluconazole. Observational series have reported that these patients require 7 to 14 days of topical azole therapy, rather than a one to three day course.181 A randomized trial demonstrated that two doses of oral therapy 72 hours apart were more effective than one dose.182 Comparative trials of topical versus oral treatment of complicated infection have not been performed. Since the oral anti-fungals can take 48 hours or more to reduce inflammation and promote improvement of symptoms, a topical anti-fungal or a low potency topical corticosteroid applied to the vulva (in addition to the oral medication) for 48 hours can be helpful.

Table P-8: Treatment of complicated candida vulvovaginitis (intractable Candida Albicans, non-pregnant patient)

| Intravaginal agents for complicated Candida vulvovaginitis | Oral agents for complicated Candida vulvovaginitis |

|---|---|

| Any intravaginal azole used for 7-14 days | Fluconazole 150 mg orally x 1 and again in 72 hours; in severe cases, may be used a third time. (Avoid in pregnancy). |

| Ibrexafungerp 150 mg tablets by mouth twice daily. The optimal duration of therapy is unknown. Avoid in pregnancy. |

Treatment of recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis (RVVC)

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis is defined as three or more episodes of symptomatic infection within one year. Vaginal cultures should always be obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to identify less common Candida species. In most people, recurrent disease is due to relapse from a persistent vaginal reservoir of organisms or endogenous reinfection with an identical strain of susceptible C. albicans, but 10-20% of recurrent infections are from a different candida strain, often a non-albicans species. Some patients exhibit an immune hyper-reactivity to Candida due to mutations and genetic polymorphisms of innate immune genes which alter the vaginal mucosal immune response to Candida challenge.

Treatment strategy for recurrent infections includes an induction phase followed by maintenance:

Induction: Any topical agent vaginally X 7-14 nights, or oral fluconazole 150 mg orally every 72 hours for three doses, or Itraconazole 200 mg orally twice daily X 3 days

Topical induction regimens include:

- Clotrimazole 1% vaginal cream for 7-14 nights

- Miconazole 2% vaginal cream for 7-14 nights

- Miconazole 100 mg vaginal suppository for 7-14 nights

- Clotrimazole 2% vaginal cream for 3-7 nights

- Miconazole 4% vaginal cream for 3-7 nights

- Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository once

- Miconazole 200 mg vaginal suppositories for 3-7 nights

- Tioconazole 6.5% ointment for one night

- Terconazole 0.4% vaginal cream for 7-14 nights

- Terconazole 0.8% vaginal cream for 3-7 nights

- Terconazole 89 mg vaginal suppository for 3-7 nights

- Butoconazole 2% vaginal cream single dose

Maintenance: Fluconazole 150 mg orally once per week X 6 months, or Itraconazole 100-200 mg orally twice weekly for 6 months, or miconazole 2% vaginal cream 5 gms vaginally twice weekly X 6 months, or miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository once weekly X 6 months, or clotrimazole 1% vaginal cream 1 applicator twice weekly X 6 months, or terconazole 0.4% vaginal cream twice weekly X 6 months.

After 6 months of suppressive therapy, a trial of drug discontinuation is recommended. Some patients will enjoy a prolonged remission after maintenance, but up to 55% will relapse and will need longer term suppression, often for additional months or years. Due to the safety profile and low plasma concentrations of once-weekly 150 mg fluconazole, most experts do not recommend laboratory monitoring during maintenance therapy.183

Oteseconazole was FDA approved in 2022 as a new oral azole antifungal to reduce the incidence of recurrent candida vulvovaginitis (RVVC). This is the first drug to be approved in the US specifically for treatment of RVVC. Oteseconazole is active in vitro against most isolates of C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae and C. dubliniensis. It is active against fluconazole-resistant isolates. Its mechanism of action is the same as other azoles, inhibition of fungal sterol 14⍺-demethylase (CYP51), an enzyme which aids in synthesis of fungal cell membranes. Adverse effects include headache and nausea. The drug has a 128 day half-life, and persists in tissues for many months. In two clinical trials oteseconazole recipients had fewer RVVC episodes and experienced a greater recurrence-free time interval compared to patients receiving placebo during a 48 week study period. Ocular abnormalities were observed in the offspring of pregnant rats given oteseconazole, and the drug is contraindicated in females of reproductive potential (including those using effective contraception) and in pregnant and lactating women.The drug should be taken with food to aid absorption and swallowed whole (not chewed, crushed, dissolved or opened. It is not recommended in patients with renal impairment or severe hepatic impairment. The medication comes in a blister pack to facilitate dosing. The cost of an 18 capsule course of therapy in 2022 was $2700.184.

Single Drug RVVC Treatment with Oteconazole: 600 mg orally on day 1, 450 mg orally on day 2, followed by 150 mg orally once weekly for 11 weeks, starting on day 14.

Dual Drug RVVC Treatment: Induction with fluconazole 150 mg orally on days 1, 4, and 7. Then suppressive therapy with oteseconazole 150 mg orally once a day for 7 days on days 14 through 20, followed by oteseconazole 150 mg orally once per week. 185

Treatment of non-albicans yeast

Non-albicans organisms commonly fail treatment with azoles (around 50 percent). Fluconazole resistance has been reported in some case studies of immunosuppression and systemic cases and is not recommended as first line therapy for non-albicans yeast.186 Treatment with terconazole 0.4% cream for seven days is reported to have a 56% mycological cure at one month,187 but this may be an over-estimate since the study did not track patients who refused terconazole because it had not worked before. Moderate success (65 to 70 percent) in women infected with non-albicans Candida with intravaginal boric acid (600 mg capsule inserted vaginally once daily at night for two weeks).188. But boric acid capsules used vaginally may be irritating. They can be fatal if swallowed, and there are no safety data on long term use. Most appropriate use currently appears to be for proven azole-resistant, non-albicans Candida.189

A 90 percent cure has been achieved with intravaginal flucytosine cream 10% (5 g vaginally nightly for two weeks),190 but the expense of the medication is prohibitive for some. Amphotericin B suppositories (50 mg intravaginally nightly for 14 days) are also of value in the treatment of non-albicans yeast. Boric acid capsules, amphotericin, and flucytosine cream are not available commercially and must be made by a compounding pharmacy.

Table P-9: Treatment of non-albicans yeast (not always necessary: rule out other causes to be sure non-albicans candida may be causing symptoms)

| Intravaginal agents for culture-proven non-albicans Candida in symptomatic women | Oral agents for culture-proven non-albicans Candida in symptomatic women |

|---|---|

| Compounded boric acid suppositories, 600 mg intravaginally, nightly x 14 days | Fluconazole is usually not effective in treating non-albicans candidiasis. |

| If not effective, follow a second treatment with boric acid intravaginally, 600 mg nightly x 14 days with nystatin cream: 100,000 units vaginally nightly for 21 days | Ibrexafungerp 300 mg orally every 12 hours X 2 doses. |

| If not effective, follow the second treatment with compounded flucytosine cream 10%, 5 grams intravaginally for 14 days, or Amphotericin B compounded suppositories, 50 mg intravaginally nightly for 14 days or or amphotericin B cream 3-4%, 5 gms vaginally at bedtime X 14 days | For C. krusei: Itraconazole 200 mg orally twice daily X 7-14 days. |

| Gentian Violet 1% solution: soak a tampon in 0.5 ml, place vaginally x 3-4 hours twice daily for up to 12 days. Will stain clothing. | Ketoconazole 400 mg orally daily X 7-14 days |

| For C. krusei: (typically resistant to oral fluconazole and flucytosine) | |

| Topical clotrimazole, miconazole, or terconazole vaginally X 7-14 days. | |

| Boric Acid 600 mg vaginal capsules or suppositories at bedtime X 14 nights | |

| Amphotericin B 3-4% vaginal cream or 100 mg vaginal suppositories at bedtime X 14 | |

| For C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae and C. kefyr: sensitive to azoles, which are first choice of therapy | |

| For C. dubliniensis: Boric Acid 600 mg vaginal capsules or suppositories at bedtime X 14 nights | |

| For Saccharomyces cerevisiae: resistant to fluconazole. Treat with topical clotrimazole or miconazole first. If not successful, use boric acid. |

Pregnancy

Treatment of Candida in pregnant women often fails to clear the pathogen and is usually indicated only for relief of symptoms. There is no association with adverse outcomes from vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy.191 Any of the topical azoles used vaginally for seven days is appropriate. Vaginal nystatin is another option, for 7 to 14 days. Avoid fluconazole, flucytosine, boric acid, amphotericin B and itraconazole in pregnancy.

There are several published case reports of birth defects in infants whose mothers were treated with high-dose fluconazole (400-800 mg/day) for serious and life-threatening fungal infections during most or all of the first trimester.192 193 The features seen in these infants include cranio-facial abnormalities, bony abnormalities, muscle weakness and joint deformities, and congenital heart disease. Based on this information, the pregnancy category for fluconazole indications (other than vaginal candidiasis) has been changed from category C to category D. 194 The pregnancy category for a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg to treat vaginal candidiasis has not changed and remains category C. Pregnancy category D means there is positive evidence of human fetal risk based on human data but the potential benefits from use of the drug in pregnant women with serious or life-threatening conditions may be acceptable despite its risks.