Annotation M: Speculum exam and examination of the cervix.

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationNote: this annotation is undergoing updating (9-14-24); please forgive any confusion!

The cervix represents the transition between the vagina and lower genital tract, and the uterus and upper genital tract. Aside from the importance of cervical cancer screening, evaluation of the cervix is an essential component of the vulvovaginal examination, since the cervix can be the source of discharge and irregular bleeding. It is a source of dyspareunia from discomfort with deep thrusting during intercourse; it is not a source of intromission dyspareunia or vulvar pain.

Abnormalities of the Papanicolaou smear and cervical HPV testing are minimally considered here since they are a rare source of vulvovaginal symptoms and are thoroughly discussed by other authorities. Current cervical cancer screening and management algorithms are found at the website for the ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology).

Infectious (mostly caused by sexually transmitted infections) and non-infectious cervicitis is covered in this section, but the most comprehensive coverage for these conditions can be found in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2021 guidelines; the link takes you to all conditions in one place in PDF format. (Be sure to use the back arrow to return to the V Disorders.org website). These guidelines do cover HPV, as well, in all of its forms. Cervical HPV can have implications for vaginal, vulvar, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer, all addressed elsewhere in the website.

The cervix (Latin, neck) is divided into vaginal (portio or ectocervix) and supravaginal (isthmus) portions. It acts as the transition from the lower to upper genital tract. The vaginal portion of the cervix protrudes through the upper, anterior vaginal wall. Approximately half its length is visible; the remainder lies above the vagina beyond view. The portion projecting into the vagina is referred to as the portio vaginalis or ectocervix. On average, the part of the cervix visible to the examiner is 2.5-3 cm long and 2.5 cm at its widest point. The size and shape of the cervix varies widely with age, hormonal state, and parity. The cervix may vary in shape from cylindrical to conical;1 in parous women, the cervix is barrel-shaped and the external os, or lowermost opening of the cervix into the vagina, appears wider and more slit-like and gaping than in nulliparous women. Before childbearing, the external os is a small, circular opening at the center of the cervix.

The passageway between the external os and the endometrial cavity is referred to as the endocervical canal. The canal runs through the supravaginal portion of the cervix or isthmus to the uterine body. The canal measures 7 to 8 mm at its widest in reproductive-aged women.2 Its upper boundary is the internal os.

Histology

The ectocervix varies widely in length and width, along with the cervix over all. It is covered with squamous epithelium, continuous with that of the vagina. The endocervix is covered by a single layer of tall, columnar, epithelial cells, and, unlike the vagina, contains numerous glands responsible for mucus secretion. When a gland ostium is occluded, secretions accumulate, producing commonly seen nabothian cysts (see below) that are visible as small, blue-gray, bubble-shaped structures.

Physiology

Cervical glands secrete mucus that is alkaline and nutritive for spermatozoa, and has bacteriocidal properties, effective in preventing ascending vaginal infection. The cervical epithelium undergoes cyclic changes during the menstrual cycle. During the proliferative phase, mucus is scant, opaque, and viscous.

At midcycle and ovulvation, cervical secretions are abundant and less viscous, rich in carbohydrates and amino acids favorable to sperm migration.

With the rise of progesterone in the luteal phase, secretions become yellowish and more viscous again.

Blood Supply

The blood supply of the cervix derives from the internal iliac arteries, which give rise to the uterine arteries. Cervical and vaginal branches of the uterine arteries supply the cervix and upper vagina. There are considerable anatomic variations and anastomoses with vaginal and middle hemorrhoidal arteries. The cervical branches of the uterine arteries generally descend on the lateral aspects of the cervix at three and 9 o’clock. The venous drainage of the cervix parallels the arterial supply, eventually emptying into the hypogastric venous plexus.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the cervix is complex and variable and includes the common, internal, and external iliac nodes, the obturator and parametrial nodes, and numerous other groups as well. The primary route of spread of cervical cancers is through the lymphatics of the pelvis.

Support and nerve supply

The main support structures of the cervix are the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. These attach to the lateral and posterior aspects of the cervix above the vagina and extend laterally and posteriorly to the walls of the bony pelvis. The uterosacral ligaments contain the main nerve supplying to the cervix, derived from the hypogastric plexus. Sensory, sympathetic, and parasympathetic fibers are present in the cervix- the reason that instrumentation of the endocervical canal (dilatation and/or curettage) may result in a vasovagal reaction with reflex bradycardia in some patients. The endocervix also has a plentiful supply of sensory nerve endings, while the ectocervix has fewer nerve endings.

All specula were formerly made of metal, and sterilized after use. However, many, especially those used in emergency rooms and physicians’ offices, are now made of plastic, and are sterile, disposable, single-use items. Specula come in a variety of shapes and lengths. A drawer with some of each is suggested for the vulvovaginal examining table. For standard office vaginal examination, a sterilized metal speculum with two blades (bivalved) allows the clinician direct visualization of the area of interest and the possibility to introduce instruments for further interventions such as a biopsy. The two blades are hinged and are “closed” when the speculum is inserted to facilitate its entry and “opened” in its final position where they can be arrested by a screw mechanism, freeing the clinician’s hands from maintaining the speculum position.

The speculum examination for an initial patient is preceded by the Q-tip test (Annotation I: Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test). The vaginal pH (Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy, and cultures) is obtained at the end of the Q-tip test. Then a single finger is used for evaluation of the hymenal ring and the pelvic floor. (Annotation L: Exam of the hymenal ring and the pelvic floor). From these portions of the examination, a clinician will have a reasonable approximation of what the patient’s tolerance of the speculum will be.

A Pederson speculum, which is long and narrow, (whereas the Graves speculum is wider and generally shorter) is appropriate for vaginal examination of a woman without causing vestibular, vaginal, or pelvic floor pain. When there is a possibility of pain, a thin pediatric speculum may be appropriate. For severe pain, we defer the speculum examination entirely, and use a blindly inserted Q-tip swab to obtain secretions for a wet mount. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance for genital exam). Disposable plastic speculae, despite providing excellent light sources, are uncomfortable for many because of the awkward racheting necessary to open and secure them.

Obtain the patient’s permission, encourage her to empty her bladder, and provide an adequate drape. Assure the presence of an assistant and document the chaperone, or the fact that the patient declined an attendant’s presence. Start with the patient lying supine on the exam table with the head elevated 30 to 45 degrees. The term “scoot down to the end of the table” is offensive to many women, making them feel juvenile and demeaned. Request, instead, that the patient move her hips down to the very edge of the exam table, place her feet in stirrups, knees bent and relaxed out to the side. Adjust the angle and length to “fit” the patient. If she is not down far enough on the table, the exam will be more difficult for you and more uncomfortable for her as the speculum handle presses against the gluteal and anal areas. The inability to cooperate with assuming lithotomy position suggests a major obstacle to continuing the examination. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance for genital exam).

Padded stirrups add to comfort, but standards for changing the padding between patients must be observed.

Uncover the vulva by moving the center of the drape away from you. Try to avoid creating a “screen” with the drape pulled tight between the patient’s knees or in your line of eye contact with her. Annotation E, The detailed vulvar exam, has described the careful visual inspection, palpation and pain mapping necessary for evaluation. The Q-tip test is described in Annotation I: Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test. Reassure the patient frequently that all is going well. Complete the evaluation of the pelvic floor (Annotation L: Exam of the hymenal ring and the pelvic floor).

As you begin the speculum examination, state what you are going to do. A warmed speculum is always appreciated. Separate the labia with one hand while gently inserting the speculum with the other hand. It is frequently more comfortable for the patient if you insert the speculum rotated about 45 degrees (so the blades are not horizontal but are oblique or vertical) and remember that posteriorly is where the introitus stretches. Once past the introitus, rotate the speculum with its blades back to the horizontal position.

The labia, particularly the labia minora, are very sensitive to stretching or pinching; take care not to catch the labia minora in the speculum while inserting it. Some practitioners ask their patients to “bear down” while they are inserting the speculum and feel that this assists with insertion. Others find this instruction to be confusing. Once past the introitus, rotate the speculum to a horizontal position and continue insertion inferiorly and posteriorly until the handle is almost flush with the perineum.

Open the blades of the speculum 2 or 3 cm using the thumb lever until the cervix comes into view between the blades. If the cervix is not visible, the clinician must maneuver the speculum to find whether the cervix is anterior or posterior. Close the blades, withdraw the speculum slightly, put it gently down (posteriorly), and reinsert. Then open the blades to try to visualize the cervix. If the cervix is anterior, a less posterior angle will be necessary. In the case of difficult cervical visualization, the clinician will need to remove the speculum and palpate the location of the cervix with two fingers in the vagina in order to guide the speculum to the correct position.

Secure the speculum by turning the thumbnut (metal speculum) or clicking the ratchet mechanism (plastic speculum). Movement of the speculum while it is locked open will cause pain.

Observe the vaginal walls and fornices for color, epithelial integrity, lesions, and discharge. (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium).

Obtain a sample from the vaginal side wall for a wet mount and specimens for any cultures or adjuvant testing that may be indicated. (Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy, and other testing).

After exam of the cervix is complete and any necessary testing done, loosen the speculum and allow the blades to fall together slightly. Continue to withdraw while rotating the speculum to 45 degrees and observing the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Then perform a bimanual examination that includes assessment for cervical motion tenderness and uterine and adnexal pain, hallmarks for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). (Annotation Q: Bimanual exam).

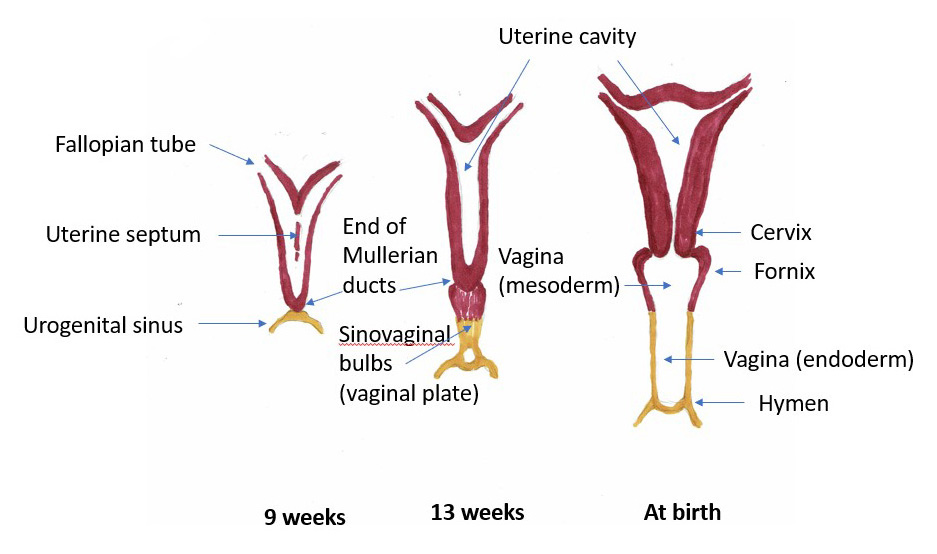

In a female fetus, the uterus and cervix start out as two small tubules, the müllerian ducts. (Johannes Muller, 19th century German anatomist). As the fetus develops, the ducts normally join to create one larger, hollow organ — the uterus with its cervix. Duplication of the cervix can occur if one or both müllerian ducts fail to fuse. Agenesis of the cervix can occur if development of one or both Müllerian ducts fails to occur, or is incomplete. Since abnormalities of the mesometanephric duct from which the urinary system arises frequently occur in association with abnormalities of the müllerian ducts, coexistent anomalies of the vagina, uterus, and urinary tract are common.

Duplication

Duplication of the cervix (cervix duplex) may manifest as two distinct cervices or two fused cervices. Determining if there are two separate cervices or a single septated cervix may require combined ultrasound and MRI imaging.

Nonobstructive duplication of the cervix is usually asymptomatic and does not require intervention. Obstructive lesions require surgical intervention if hematometra or pyometra occurs.3

Agenesis/hypoplasia

Cervical agenesis and hypoplasia are rare. With complete agenesis, both the cervix and the upper vagina will be absent, as the proximal portion of the vagina does not form in the absence of a cervix during embryonic development. When the cervix is present, but hypoplastic, the vagina can be normal.

Cervical hypoplasia is usually diagnosed at menarche when the adolescent presents with primary amenorrhea, cyclic or chronic abdomino-pelvic pain, or a pelvic mass (from hematometra). Imaging with ultrasound and MRI are helpful in diagnosis. Surgical procedures to address the problem continue to evolve, although suppression of menstruation to prevent hematometra and assisted reproduction are now possible.4 5 The adolescent would need referral to an academic medical center.

Ectropion

Introduction/definition

Cervical ectropion or eversion is a harmless condition often confused with cervicitis and even cervical malignancy. Ectropion represents the outward eversion of the columnar epithelium from the endocervix out onto the visible ectocervix, exposing the columnar epithelium to the vaginal environment. The degree of ectopy can be estimated by colposcopy, comparing the radius of columnar epithelium on the ectocervix relative to the radius of the entire ectocervix.6

In the past, ectropion was called cervical erosion. This is an inaccurate term since an erosion represents the loss of part of the cervical surface epithelium of superficial squamous cells due to a pathologic process. Cervical erosions and ulcers can be seen in infections and inflammatory states. An ectropion represents no such pathology but is seen in areas of the portio of the cervix where squamous cells have been overgrown by columnar epithelium.

Prevalence and etiology

Ectropion is common. It can occur under the influence of high estrogen states such as adolescence, pregnancy, and estrogen /progesterone contraceptives. It may be seen related to the positioning of the speculum, when the blades stretch the cervix in such a way that the endocervix is exposed. As the blades are closed, the appearance of ectropion disappears. It is also seen after childbirth with cervical laceration that has exposed the endocervical canal, with subsequent outgrowth of columnar cells onto the portio.

Symptoms and clinical features

Cervical ectropion often causes no symptoms, but can produce a constant, annoying non-purulent mucus discharge from the increased surface area of columnar epithelium containing mucus-secreting glands. It may also give rise to post-coital bleeding as fine, surface blood vessels within the outgrowth of columnar epithelium are traumatized with intercourse.

Diagnosis

Cervical examination reveals circumferential or focal plush, fiery red tissue around the cervical os, similar to granulation tissue. A yellowish exudate may cover the surface, along with areas of friability. If there is a question about pathology, colposcopy will reveal the normal tissue of the endocervical canal. Biopsy can be done if there is uncertainty. Chlamydia (CT) and Gonorrhea (GC) testing should be done. Pap smear and/or HPV testing should be done in women over 21, unless confirmed as normal in the past year. See ACOG 2021 (reaffirmed April 2023) Guidelines for more specifics.

Differential diagnosis

Cervicitis, herpes simplex, intraepithelial neoplasia, and cervical malignancy can be confused with cervical ectropion. Cervical ulceration can be caused by herpes, syphilis, or chancroid, (See cervical ulcers below).

While desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) may inflame the squamous epithelium of the cervix contiguous with the upper vagina, this is not the endocervical eversion of an ectropion.

Treatment

Asymptomatic cervical ectropion requires no treatment. For symptomatic ectropion, the birth control pill can be discontinued; it may take several months for the ectropion to regress. Ablation of the area with cautery under local anesthesia is suggested by some, but involves weeks of post-ablative discharge, the risk of scarring, and recurrence of the ectropion. In a general low risk for STI population, ectropion should be considered a normal variation. However, ectropion has been associated with cervicitis.

Cervicitis

Introduction

Cervicitis was first identified as a clinical entity in 1984. The term mucopurulent cervicitis was used to describe cervical inflammation, characterized by what was then called yellow mucopus- endocervical discharge that is yellow on a white cotton-tipped swab, or greater than 10 polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high power field on microscopy.7 2021 criteria from the CDC state that one or both of the two following criteria meet the definition for cervicitis: “1) a purulent or mucopurulent endocervical exudate visible in the endocervical canal or on an endocervical swab specimen, or 2) sustained endocervical bleeding easily induced by gentle passage of a cotton swab through the cervical os.”8 The criterion pertaining to the number of white cells on a microscopy slide or Gram stain is no longer considered specific, reliable, or available enough to be of use. On the other hand, absence of excessive white blood cells on microscopy can reassure against a diagnosis of cervicitis.

In current terms, cervicitis represents either acute or chronic inflammation, usually of the columnar epithelial cells of cervical glands; the inflammation may also affect the squamous cells of the ectocervix. The inflammation arises from infectious or non-infectious causes.9 See this topic covered by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021 guidelines for urethritis and cervicitis.

Prevalence and etiology

Few population based data are available, but cervicitis is common in women and may be seen in a variety of clinical settings.10 A 2013 study of the prevalence and treatment outcome of cervicitis of unknown cause,11 in agreement with previous studies, showed a 23% prevalence of clinical mucopurulent cervicitis in women with a mean age of 33. Only 20-24% of patients in this study and in others had culture or NAAT positive chlamydia or gonorrhoea and in 61% no cause for the cervicitis was found.12 13 That is, NAAT testing was negative for CT, GC, trichomoniasis (TV), or mycoplasma genitalium (MG).

Non-infectious etiology of cervicitis

Mechanical or chemical causes of noninfectious cervicitis

A variety of mechanical or chemical irritants play a role in noninfectious causes of cervicitis. Substances that erode the cervicovaginal mucosa or cause an irritant mucositis, including douches, latex, some spermicides, chemical deodorants, and contraceptive creams, should be considered as potential causes of chemical irritation.14 Mechanical causes of cervicitis include the string from an intrauterine device, cervical cap or diaphragm, pessary, or tampon. The rare multi system vasculitis (ophthalmic, neurological, gastro-intestinal, genital) of Behçet disease, for which systemic criteria now exist, (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) and radiation therapy, are possible non-infectious causes.

Relationship of non-infectious cervicitis to inflammation on Pap smear

In 1995, studies were done on women with inflammatory Pap smears. The first showed that inflammatory smears were more likely to be associated with bacterial vaginosis, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus, but 12% of women with inflammatory smears had no evidence of infection.15 In the other studies, two populations were used, one from a sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic, the other at a university health center. In the STI population, inflammation was associated with ectopy, mucopus, and positive cultures for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis or herpes simplex. In the student population, mucopus, and ectopy were associated, but 95% of the women with a densely inflammatory Pap smear did not have N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, HSV, or trichomonas.16

We know, therefore, that sexually transmitted disease, chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and herpes simplex are associated with an inflammatory Pap smear, and that those patients need appropriate evaluation for possible infection likely in an STI population. However, in a low-risk population, traditional infectious causes of cervical inflammation that result in an inflammatory Pap smear seem to be uncommon.17

At the same time, severe inflammation found on cervical cytology (Pap smear) has been shown to be correlated with increased risk of high grade intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) of the cervix,18 so careful evaluation is a priority.

As tests are improved and made more available, our ability to identify infectious causes will undoubtedly be increased exponentially.19 Understanding of the vaginal microbiome and its influence throughout the anogenital track will further enhance the ability to identify causes of both infectious and non-infectious cervicitis.

Infectious etiologies of cervicitis

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea

Chlamydia and N. gonorrhoea are the most common causes of infectious cervicitis. Depending on the population sampled, chlamydia is the most frequently identified cause with population- dependent rates of 11-15%20 and is the most highly reported bacterial infection in the United States, with prevalence highest amongst those age 25 or less.21 N. gonorrhoea is the second most highly reported bacterial infection in the United States. Both may be asymptomatic. With gonorrhoea, by the time symptoms appear, fallopian tube damage in the form of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) may have occurred.22 Chlamydia can also lead to cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, and ectopic pregnancy.

Chlamydia trachomatis and N. gonorrhoea, along with mycoplasma genitalium and trichomonas vaginalis had the strongest associations with cervicitis in a 2016 study using three cervicitis definitions: microscopy (>30 polymorphonuclear leucocytes per high-powered field on cervical Gram stain), cervical discharge (yellow and/or mucopurulent cervical discharge), or combined microscopy and cervical discharge findings.23 Cervicitis has also been found associated with HSV-2 infection (usually in the case of primary disease). At this time, there is no known association between group B strep colonization or ureaplasma parvum or ureaplasma urealyticum and cervicitis.24 In some cases of high suspicion for STI, no organism is identified.

Mycoplasma genitalium

M. genitalium has been associated with cervicitis, PID, preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, and infertility, with an approximately twofold increase in the risk for these outcomes among infected women, according to the CDC.25 Women with PID are more likely to test positive for M. genitalium than women without PID. However, there are no data that show that treating this organism prevents PID or endometritis.26 Infection with M. genitalium may also be asymptomatic, confounding the ability to track it.

Although there is strong support for M. genitalium in the etiology of some forms of cervicitis,27 28 with the CDC noting that 10-30% of patients with cervicitis test positive for it in clinical trials,29 the low M. genitalium prevalence in asymptomatic women and paucity of randomized controlled studies30 do not justify routine screening, and testing is not yet available for the general clinician.31 33 Calls for greater attention to M. genitalium and for availability of routine testing have occurred34 and the CDC does now state that 1) women with recurrent cervicitis should be tested for M. genitalium and 2) M. genitalium testing should be considered among women with PID, especially those who do not respond to antibiotics used for PID. Testing should be accompanied with drug resistance screening, if available.35 M.Genitalium does not respond to antibiotics that target cell walls and Azithromycin 1 g has shown resistance and is not recommended for treatment. The CDC has detailed information about treating this infection. (See below).36

Trichomonas vaginalis

Trichomonas has an association with cervical inflammation,37 but cervical inflammation from trichomonas is not common and varies with local prevalence; trichomonas infection also increases risk of HIV transmission.38 T. vaginalis causes erosive inflammation of the ectocervical squamous epithelium, the classic colpitis macularis or “strawberry cervix.” The organism elaborates a variety of cytotoxic factors including cysteine proteases to degrade cervicovaginal epithelial protective factors, most notably secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor.39

Trichomoniasis is thought to be under-diagnosed because of the low sensitivity of wet-mount microscopy. Patients with cervicitis should undergo specific testing for Trichomoniasis and be treated appropriately.40 See more on trichomoniasis in Annotation P.

Herpes simplex

HSV-1 and HSV 2 can both cause cervicitis.41 HSV cervicitis is not common; it is most obvious in women with severe clinical manifestations of primary HSV-2 infection, manifesting with diffuse erosive and hemorrhagic lesions in the ectocervical epithelium, often accompanied by frank ulceration. Herpes-related cervicitis may accompany clinical recurrences of genital HSV-2, usually less severe that that seen during primary infection.42 The manifestations of HSV-1 cervicitis are usually less severe and occur only during the primary genital infection. Subclinical shedding of HSV-2 does not appear to be directly related to cervicitis.43

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

There is no evidence that human papillomavirus (HPV) infection induces cervical inflammation on clinical exam,44 but HPV is a co-factor in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. One study states that, in the presence of severe inflammation on Thin prep cytology, the risk of HSIL was over 750 times higher than in the patients who had no inflammation.45

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis is found in up to 50% of women with cervicitis and has been thought to play a role in its etiology.46 The loss of hydrogen peroxide/lactic acid-producing lactobacilli in conjunction with the increase in sialidases and glycosidases produced in bacterial vaginosis has been thought to break down the protective cervical mucus barrier,47 creating inflammation not previously thought to be a feature of bacterial vaginosis. But a 2016 Australian study did not find bacterial vaginosis associated with cervicitis.48 See more on Bacterial Vaginosis in Annotation P.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend that bacterial vaginosis be treated if present with cervicitis.49

Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Group B Beta-hemolytic Streptococci

These organisms are normal inhabitants in the genital tracts of sexually active women. Association with cervicitis has been suggested, but there is scant evidence that they cause cervicitis.50 51

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

CMV has also been isolated from women with cervicitis.52 Whether this virus contributes directly to cervical inflammation or is simply shed in higher concentrations during episodes of cervicitis is not known.53 There are no data with regard to efficacy of antiviral therapy to alleviate the symptoms of cervicitis.54

Cervical ulceration with infections less common in the United States

Cervicitis and ulcerations may be seen with sexually transmitted infections not commonly seen in the United States, but contacted by sexual activity with partners from or US military troops stationed in Southeast Asia, Africa or the Caribbean. Syphilis can produce cervical ulceration at any stage. Granuloma ingiunale generally involves the vulva, but causes cervical ulceration in advanced, untreated disease. Chancroid also can rarely cause cervical ulceration.55 See cervical ulcers below.

Tuberculosis is also a rare cause of vulvar and cervical ulcerations.56 Tuberculosis is covered at CDC Guidelines for tuberculosis, 2021.

Complications with cervicitis

Cervicitis, when infectious in etiology, can lead to a number of complications including endometritis and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), as well as adverse outcomes of pregnancy and impact on the newborn. Enhanced transmission of HIV results from the relationship between genital infection and the HIV virus. A relationship between cervical inflammation and cervical cancer may exist.

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Cervicitis predicts upper genital tract disease and can be a marker of subclinical PID. In some women, cervicitis and endometritis may be the only signs of PID,57 and subclinical PID is thought to be a contributing factor of tubal-factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain in women who give no history of PID.58 The presence of vaginal mucopus (>10 leucocytes per high-powered field on microscopy of vaginal secretions) may be useful in the diagnosis of upper-genital tract infection.59

In women with mucopus from nongonococcal, nonchlamydial cervicitis, the links to upper tract disease have not been established.60

Cervicitis in pregnancy

Cervicitis has been associated with the delivery of low-birth-weight babies,61 and antibiotics administered to women with preterm labor resulted in significantly lower neonatal morbidity and mortality in a sub-group with NSC.62 In a recent study, ectopic pregnancy rates doubled in the presence of Chlamydia infection.63 The CDC recommends that pregnant women with cervicitis be treated in the same way non-pregnant women are.64

HIV transmission

HIV-related genital ulceration, especially herpes simplex (HSV)-related ulceration, is known to increase risk of HIV transmission.65 Cervicitis probably increases susceptibility to HIV infection and increases viral shedding by means of inflammation and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, disruption of mucosa, and increased numbers of HIV-infected cells in cervical secretions.66

Clinical features and diagnosis of cervicitis

Cervicitis may be asymptomatic. The symptomatic woman will complain of vaginal discharge and post-coital or intermenstrual spotting and staining. Vulvovaginal irritation and deep dyspareunia may be problems. If there is urethral infection present with chlamydia, urinary tract symptoms may be present.

On physical examination, the classic signs of mucopurulent discharge (yellow discharge on a white cotton-tipped swab) and/or easily induced bleeding (friability), will be present at the cervical os.67 Cervical motion tenderness (suggestive of concomitant pelvic inflammatory disease) may be present.

While the presence of >10 leukocytes per high power filed was an original criterion, the presence of >30 polymorphonuclear leukocytes/high power field by microscopy on a cervical specimen combined with one or both of the above signs, improves the accuracy of diagnosis.68

Testing to be done:

- pH, KOH, and wet mount for bacterial vaginosis and trichomonads. If microscopy is negative for trichomonads, culture or nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) should be done. For heavy vaginal discharge, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) should also be suspected.

- Nucleic acid amplification testing for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis: These assays can be performed on a swab of vaginal fluid, an endocervical sample (cells are obtained by rotating a swab within the endocervical canal ) or, if a speculum examination is not possible, on a vaginal swab specimen without speculum, or on urine.69

- A diagnostic test for M. genitalium is not commercially available. There is generally no role for other bacterial cultures or PCR, which can be very expensive and often detect vaginal bacteria that are unrelated to the cervical process.70

- Testing for syphilis, LGV, GI, and chancroid would be necessary if the patient is from an area or has a sexual partner from an area where there is a high prevalence of these diseases.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes cervical ectropion, trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma, HIV, herpes simplex 1 or 2, CMV, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, vaginal lichen planus. Syphilis, LGV, GI and chancroid may present with cervicitis in some populations. Tuberculosis is rare.

Treatment of non-infectious cervicitis

For women with cervicitis that appears to be associated with a chemical or mechanical cause, removal/avoidance of the foreign body/substance will often lead to resolution of inflammation. Therefore, chemical douches, vaginal contraceptives and deodorants, and pessaries should be discontinued and the patient followed to see if there is a therapeutic response. Topical or antibiotic treatment is not useful in this setting.

Treatment of infectious cervicitis

Providing presumptive therapy without culture or NAAT results for C. trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae is necessary for the following women with cervicitis:71

- women 25 years or less,

- women with new or multiple sex partners and

- women who engage in unprotected sex

- women for whom follow-up cannot be ensured

- women for whom a relatively insensitive diagnostic test is used in place of nucleic acid testing

CDC recommended treatment for suspected infectious cervicitis is Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for seven days (alternative treatment Azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose) plus concurrent treatment for N. Gonorrhea depending on index of suspicion and local prevalence:

- Weight <150 kg (300 lbs) – Ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly once

- Weight ≥150 kg (300 lbs) – Ceftriaxone 1 g intramuscularly once

and treatment of BV and trichomonas if found.

Recommended regimens for treatment of C. trachomatis can be found at the CDC website: Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, chlamydia.

Recommended regimen for uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra and rectum can also be found at the CDC website: Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, gonorrhea.

Recommended treatment for bacterial vaginosis: Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, BV.

Recommended treatment for trichomoniasis: Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, trichomoniasis.

Recommended treatment for herpes simplex: Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, herpes simplex.

Management of cervicitis in which an infectious agent has not been identified during the diagnostic evaluation is controversial, although this is a common clinical scenario. There is no strong evidence to justify suggesting one treatment approach over another. If the patient has not received any treatment, treatment is recommended to cover gonorrhea and chlamydia, as discussed above.

Sex partners of women with chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomoniasis should be treated for the sexually transmitted infection for which the woman received treatment. To avoid reinfection, patients and their sex partners should abstain from sexual intercourse until therapy is completed (seven days after a single-dose regimen or after completion of a seven-day regimen).

Chronic cervicitis

The natural history of cervicitis is not defined, and the benefit of further antibiotic treatment of unresponsive cases and their partners has not been well studied.

In the case of what appears to be chronic cervicitis, evaluate for possible re-exposure to an STI. Repeat testing for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae and re-treat if necessary. Evaluate and treat for bacterial vaginosis (BV) and trichomoniasis. Culture for herpes simplex (HSV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV); if positive, viral suppression with acyclovir 400 mg twice daily may be initiated although there is no evidence for efficacy. Call your state laboratory to find out if testing for Mycoplasma genitalium has become available. If not, consider treatment with moxifloxacin 400 mg orally 24h for five days.

Consider chemical irritants, e.g. sustained use of commercial products that could disrupt or irritate the cervical mucosa, particularly over-the-counter surfactants, or potentially irritating substances such as betadine, cornstarch, and topical anesthetics.72

Inflammation on cervical cytology is a common finding but not necessarily an indication for treatment. The presence of a few lymphocytes on cytological smears is normal and should not be misdiagnosed as inflammation. Likewise, treatment is not indicated for asymptomatic women who undergo cervical biopsy for the evaluation of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and are found to have histologic, but no clinical, evidence of cervicitis. Histological inflammation is a poor indicator of a specific infection.73 On the other hand, repeated inflammation on Pap smear cannot be viewed in isolation and ignored as insignificant.

If relapse or reinfection of STI is ruled out, BV is not present, and sex partners have been evaluated and treated, women with persistent cervicitis should be reevaluated. Consideration of occult cervical disease is important. Hysteroscopy with biopsy and cultures may be done. Evaluation of the cervix for occult disease by an experienced colposcopist with biopsies is also recommended.

Ectopy has been associated with cervicitis.74 If ectropion is present and STI testing is negative, it is possible that the cervicitis is a physiologic process linked to ectopy. Discontinuing oral contraceptives or other hormonal therapy with estrogen may be helpful. Ablative therapy with laser has been used to treat chronic cervicitis,75 but diagnosis did not include PMNs by microscopy and culture status of the patients was not clear. Cryotherapy or laser ablation of the cervix can be offered to a thoroughly evaluated woman with severe symptoms and an understanding of lack of data for the effectiveness of this therapy. Weeks of watery discharge follow any cervical ablation.

Cervical ulcers

(For vulvar ulcerations see Annotation H: The vulvar skin, Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) Genital ulcers from four sexually transmitted infections may involve the vagina and cervix:

- herpes simplex

- syphilis

- granuloma inguinale

- hemophilius ducreyi (chancroid)

Cervico-vaginal herpes ulcers

Prevalence

In the United States, herpes is among the top causes of genital ulceration. Women are four times more likely to be infected with HSV-2 than men are. For some reason, women have more severe disease and more complications during the first infection than men. Cervico-vaginal ulcerations are most frequently seen with the first infection.76

Symptoms and clinical features

Lesions begin as a vesicle with an incubation period of 2-7 days. Multiple lesions may coalesce to a painful, necrotic, exophytic mass on the cervix or vaginal wall. Bilateral tender lymphadenopathy may be present.

If a woman develops a herpes outbreak on the cervix or vagina and not externally, she may develop vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, or burning with urination. With the first outbreak, some women may experience a second round of blisters or ulcers in the second week.77

Diagnosis

Cell culture and PCR are the preferred HSV tests for women with genital ulcers.78 Herpes serology must be ordered with caution; the time it takes for IgG antibodies to reach detectable levels can vary from person to person. For one person, it could take just a few weeks, while it could take a few months for another. So even with the accuracy of herpes serology testing, a person could receive a false negative if the test is taken too soon after contracting the virus. For the most accurate test result, it is recommended to wait 12 to 16 weeks from the last possible date of exposure before getting an accurate, type-specific blood test in order to allow enough time for antibodies to reach detectable levels.79

Differential diagnosis

Syphilis, chancroid, cervical carcinoma

Treatment

Center for Disease control and Prevention, 2021, herpes simplex

Cervical ulceration of syphilis

Prevalence

In the United States, health officials reported over 36,000 cases of syphilis in 2006, including 9,756 cases of primary and secondary syphilis. Between 2005 and 2006, the number of reported primary and secondary syphilis cases increased 11.8 percent.80

Etiology

Treponema pallidum, an anaerobic spirochete has the ability to penetrate skin or mucous membrane.

Symptoms and clinical features

After an incubation period of two to three weeks, a painless papule appears at the site of innoculation that can be the vagina or cervix. The papule ulcerates with a raised, indurated margin. It is our experience, however, that judging the clinical appearance of ulcers is not helpful. Non-tender adenopathy is present, often bilaterally. Multiple ulcerations may occur. Syphilis is a risk factor in the transmission of HIV.81

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is complicated by the fact that the spirochete cannot be cultured. Screening tests for the disease, Venereal Disease Research Laboratories (VDRL) slide test and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) are easily obtained. If they are positive, a specific anti-treponemal test, fluorescent-labeled Treponema antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) or the microhemagglutination assay for antibodies to T. pallidum (MHA-TP) must be done.82

Differential diagnosis

Herpes, chancroid, cervical carcinoma While false positive RPR or VDRL testing for syphilis is possible, the likelihood of both false positive RPR and VDRL, and false positive FTA-ABS and MHA-TP is remote.

Treatment

Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, syphilis

Hemophilus ducreyi (chancroid)

Prevalence

Only 30 cases of chancroid were reported in the United States in 2004, and prevalence has declined to 24 in 2007.83 Consideration of the disease is important if a patient comes from or has a partner from sub-Saharan Africa or the Caribbean.

Etiology

Chancroid is caused by the gram-negative rod, Hemophilus ducreyi with a short incubation of 3-6 days. Tissue trauma and excoriation of the skin must precede initial infection because H. ducreyi cannot penetrate the skin. A cytotoxin secreted by H. ducreyi may then play an important role in epithelial cell injury and subsequent development of an ulcer.84 The genital ulcers of chancroid facilitate transmission of HIV.85

Symptoms and clinical features

Chancroid usually manifests in the vulvar vestibule, but has been seen rarely in the vagina or on the cervix. The infection begins as an erythematous papule that rapidly evolves into a pustule, which erodes into an ulcer.86 Infected persons commonly have more than one ulcer, and the lesions are usually confined to the genital area and its draining lymph nodes. The ulcers and the lymphadenitis are painful.

Diagnosis

Sensitivity of gram stain is poor and special culture media for isolation of H. ducreyi is not widely available. PCR is also not available. Most facilities do not have the ability to make the diagnosis; clinicians are unable to base treatment decision on laboratory evidence.87

The combination of a painful genital ulcer and tender, suppurativa, inguinal adenopathy suggests the diagnosis of chancroid.88 Consultation with local public health laboratory official or the CDC is needed.

Differential diagnosis

Herpes, syphilis, cervical carcinoma.

Treatment

Center for disease control and prevention, 2021, chancroid

Cystic lesions of the cervix

Nabothian cyst

Prevalence

These cysts are so common that they are considered a normal feature of the adult cervix.89

Etiology

A nabothian cyst (mucinous retention cyst, epithelial inclusion cyst) is a mucus-filled cyst that forms when a small 2-10 mm pocket (crypt) of columnar epithelium of the endocervix becomes covered with stratified squamous epithelial cells from the ectocervix. The columnar cells continue to secrete mucus that is trapped inside the crypt now covered with squamous mucosa. Nabothian cysts often develop after childbirth or following minor trauma.

Symptoms and clinical features

The cysts vary from 3 mm to 3 centimeters in size.90 The larger ones project above the surface of the portio. They may appear translucent or opaque. A woman may palpate the cyst while checking cervical mucus or her IUD string or she may be asymptomatic. (LINK,Picture).

Diagnosis

The classic clinical appearance of translucent or opaque yellow-white cystic structure on the cervix is diagnostic. There can be multiple cysts. Colposcopy is sometimes necessary to distinguish a nabothian cyst from another cervical lesion.

Differential diagnoses

Cystic mass of cervix, ectopic pregnancy, Wolffian duct cyst

Treatment

Nabothian cysts are benign and usually asymptomatic. Treatment is not required.

Mesonephric cysts

Prevalence

Rare

Etiology

Remnants of the temporary embryonic excretory system, the mesometanephric (Wolffian) ducts, are sometimes found deep within the cervical stroma when an excised cervical tissue sample is examined pathologically. One or more of these remnants can form a cyst, which may be confused with a nabothian cyst. These cysts seldom reach a size greater than 2.5 cm, and are usually found near the base of the cervix at three and nine o’clock.91

Treatment

Intervention should be avoided in asymptomatic women since cervical scarring is a risk. A large cyst can be marsupialized.

Non-cystic cervical lesions

Cervical Condyloma

(For vaginal condyloma: Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium. For vulvar condyloma: Condyloma, Atlas of Vulvar Disorders.)

Prevalence

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection of the cervix is common. The estimated annual incidence in the United States of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) among women who undergo cervical cancer screening is 4 percent for CIN 1 and 5 percent for CIN 2 and 3.92

Etiology

HPV has over 100 strains (serotypes) that can affect any area of the body. Approximately 40 strains target the female genital mucosa resulting in lesions (warts) on the cervix, in the vagina, or on the vulva, perineum, or anal region. These types have varying potentials to cause malignant change.93 The association between HPV and cervical neoplasia is so strong that most other behavioral, sexual, and socioeconomic co-variables have been found to be dependent upon HPV infection and are not considered independent risk factors.94 In women, external HPV lesions are frequently associated with cervical lesions, including cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.95

Low-risk subtypes such as HPV 6 and 11, do not integrate into the host genome and cause only low-grade cervical lesions (CIN 1) and benign condylomatous genital warts.96 HPV 6 and 11 account for 10 percent of low-grade lesions and 90 percent of condylomatous genital warts.

Condyloma develop in the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix within the transformation zone, in foci of squamous metaplasia in the endocervix, or as skip lesions within the mature squamous epithelium. The lesions may be flat or exophytic. (PICTURE)

Symptoms and clinical features

More than 90% of cervical condyloma are flat with a smooth surface in contrast to other anogenital condyloma. They are asymptomatic. Flat condylomas are not apparent grossly, unless the cervix is painted with acetic acid and examined colposcopically, when they appear as sharply demarcated, white, slightly raised plaques.

Exophytic condyloma acuminatum can be caused by any HPV serotype but more commonly by types 6 and 11. The lesion appears white, the degree of whiteness depending on the thickness of surface hyperkeratosis. Papillary, spike-like projections are macroscopically apparent on the surface of acuminate warts and are visible as regular projections (asperites) on the surface of flat condylomas with colposcopic magnification. Many small, maculo-papular, slightly raised lesions may be seen in some cases.97

Diagnosis

Cervical condyloma are diagnosed by biopsy.

Differential diagnosis

Leukoplakia, CIN, squamous cell carcinoma

Treatment

A woman with a cervical lesion suggesting condyloma needs a Pap smear and colposcopy. Condyloma alone without CIN may be treated with trichloracetic acid weekly until disappearance. CIN requires individualized management. ASCCP

Since the entire lower genital tract is a target area for HPV infection, long-term follow-up with attention to the cervix, vagina, and vulva is necessary. The vast majority of women infected with HPV do not develop CIN or cancer. The two major factors associated with development of high grade CIN and cervical cancer are HPV subtype and persistence.98

Cervical Polyp

Prevalence and etiology

Incidence is reported as 4% of gynecologic patients.99 Cervical polyps occur in multiparous women in their 40s and 50s, and are the most common, benign, neoplastic growths of the cervix.100

The etiology is unknown. It is hypothesized that endocervical polyps represent focal hyperplasia and localized proliferation in response to local inflammation, or abnormal focal responsiveness to hormonal stimulation.101

Symptoms and clinical features

Cervical polyps are frequently asymptomatic and are noted during a routine speculum examination. The classic symptom of an endocervical polyp is intermenstrual bleeding, particularly after coitus or a pelvic examination. Some women report increased vaginal discharge. A polyp may be protruding from the external cervical os or may arise from the portio. The surface may be flesh-colored, red to purple, rough, and glistening. The color depends in part on the polyp’s origin, with most endocervical polyps cherry red and most cervical polyps grayish white.102 The size is typically less than 3 cm in diameter; however, polyps large enough to fill the vagina or presenting at the introitus have been described.103 The pedicle is usually long and thin, but may be short and broad-based. Frequent ulceration of the stalk’s most dependent portion explains the contact bleeding. (PICTURE).The soft consistency of the polyp may make it difficult to palpate.

Diagnosis

A cervical polyp is diagnosed clinically on inspection and by histology after removal.

Differential diagnosis

Includes leiomyoma and endometrial polyps.

Treatment

Small, asymptomatic polyps can be observed, but have a tendency to enlarge and bleed. Polypectomy is frequently performed, especially if the size is > 3.5 cm, if there is bleeding, or if there is excessive discharge or atypical appearance. Removal is a painless office procedure achieved by grasping the base of the polyp with ring forceps and gently twisting it off. Cauterization of the base with silver nitrate to prevent bleeding can be used. Curetting the base is recommended. Occasionally, a wide and fibrous polyp may need to be divided with long scissors; a broad and bleeding base maybe treated with chemical cautery, electrocautery, or cryocautery.

Polyps which are removed should be submitted to the laboratory for histological study because of the unlikely possibility of malignancy.104

Cervical endometriosis

Prevalence

This is a rare condition. The incidence is reported to be 1.6-2.4%.105

Etiology

Trauma from abortion, full-term delivery, cervical biopsy, cauterization, or conization may cause implantation of endometrial glands and stroma on the cervix. Secondary lesions are thought to be direct extension from other sites of endometriosis,106 or by vascular or lymphatic metastasis found deep in the cervix.107

Symptoms and clinical features

Most lesions of cervical endometriosis are apparent on speculum examination as superficial, sub-mucosal lesions. They appear as round, slightly elevated, red to dark blue areas of 2-3 mm, or may appear as light red macular lesions that may coalesce around the cervical os just before the menstrual period. The lesions often rupture related to the menstrual cycle, and do not reach a size larger than 5 mm. Nor do they form the large masses seen with other forms of endometriosis.108

Symptoms may be similar to pelvic endometriosis, so that defining typical characteristic symptoms of cervical endometriosis is challenging. Women with cervical endometriosis may be asymptomatic despite the presence of an obvious cervical lesion. On the other hand, the presenting symptoms can be diverse. Discharge, persistent post-coital bleeding, and intermenstrual bleeding are reported.109 Life-threatening hemorrhage is rare but documented, including one case after loop electrosurgical excision procedure.110 Deep dyspareunia from tender implants may occur.

Dysmenorrhea and pelvic dyspareunia are more likely due to implants at other sites in the pelvis, such as the ovary or uterosacral ligaments.111

Diagnosis

Some women are diagnosed because of an incidental finding in the histopathology from cervical biopsy or excision procedures. Abnormal Pap smears, some with atypical glandular cells (ASCUS), are not uncommon in these asymptomatic women.112

The lesions of cervical endometriosis are histologically the same as endometriosis at other sites. Excision or biopsy and pathologic evaluation are the keys to definitive diagnosis.113

Differential diagnosis

Hemorrhagic nabothian cyst, cervical gestational trophoblastic disease, and normal hyperemia of pregnancy (ruled out by negative results on human chorionic gonadotropin testing) are in the differential. Superficial endometriosis has been confused with endocervical glandular dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, which can only be excluded by biopsy.114

Treatment

Asymptomatic cervical endometriosis does not require treatment unless there is a Pap smear abnormality requiring treatment. Symptomatic cervical endometriosis, with cervical impaction dyspareunia from tender implants, irregular bleeding, and post-coital bleeding, may be treated surgically by loop electrical excision procedure or another cervical ablation technique such as laser. Systemic therapy for endometriosis is indicated if pelvic endometriosis is present.115

DES associated cervical abnormalities

Prevalence

Gross cervical abnormalities have been noted in approximately 20% of DES-exposed women. DES remained in use until 1971 in the US, later in Europe and other countries, making the youngest exposed women now in their 50s.

Symptoms and clinical features

DES associated cervical anomalies include cervical hypoplasia (resulting in hypoplastic cervical os), collars, hoods, and ectropion.116 Symptoms are uncommon but could manifest as vaginal discharge or spotting.

Diagnosis

History followed by speculum examination confirming classic cervical changes of DES exposure.

Differential diagnosis

Normal cervical variants and ectropion.

Treatment

DES-related structural cervical abnormalities do not require treatment. In fact, the DES exposed cervix has a tendency to scar, raising the risk of cervical stenosis. Procedures involving the cervix should be avoided. Benign cellular changes such as adenosis and ectropion have been reported to regress or at least not increase over time.117 118

For women with DES exposure and biopsy-proven cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology Consensus Guidelines should be followed.119 Cervical cancer screening should be performed yearly and must include samples from all four quadrants of the upper vagina.

There may be an increased risk of cervical insufficiency during pregnancy; such women are closely monitored.

Cervical adenosis and clear cell carcinoma

Prevalence

Cervical adenosis associated with DES occurs but is rare. (One report suggests that spontaneous non-DES related vaginal adenosis appears to be fairly common, present in about 10% of adult women.)120 Clear cell cancer is rare: one case per 1000 to 1 per 10,000 of DES exposed daughters with age ranging from seven to 48 years.121 But the relative risk for high grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia in DES daughters is 2.12108 (double the normal risk), highlighting the importance of the Papanicolaou smear in this group

Etiology

Diethylstilbesterol (DES) was given to women in 1950’s to prevent miscarriages. In utero DES exposure is associated with adenosis of the vagina (Annotation O: the vaginal epithelium) and cervix.122 Cervical adenosis may also be a variant of normal, and has been reported in a woman who was not exposed to DES.123

The tuboendometrial type of epithelium in the vagina and/or cervix, which is composed of mucin-free, often ciliated cells, provides the bed from which the rare clear cell adenocarcinoma arises.124

Symptoms and clinical features

Cervical adenosis consists of clusters of benign appearing columnar cells in the cervix surrounded by fibromuscular stroma. Although adenosis usually occurs deep in the cervix, it may arise superficially. The cherry red, patchy lesions of superficial adenosis can be seen on speculum examination of the cervix.125 With colposcopic magnification, the lesions appear similar to gland openings observed near the transformation zone.

Cervical adenosis unrelated to DES is thought to represent persistence of remnants of the initial müllerian cells (the anlage from which the cervix develops) beneath the vaginal plate of squamous epithelium.126 Cervical adenosis is typically accompanied by vaginal adenosis. (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium).

Cervical adenosis is usually asymptomatic, but can be associated with an increase in clear or white discharge.127 Clear cell carcinoma is associated with vaginal bleeding.

Diagnosis

Colposcopy and biopsy confirm the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Hemorrhagic nabothian cyst, cervical endometriosis, ectropion, adenocarcinoma.

Treatment

Cervical adenosis is benign. Electrocautery ablation is indicated only if symptoms are bothersome.

Clear cell carcinoma is treated like primary cervical carcinoma

Cervical leiomyomas

Prevalence

Leiomyomas are the most common tumors of the uterus, but only 3-8% of myomas are cervical.

Fibroids (leiomyomas) are monoclonal tumors; approximately half show karyotypically detectable chromosomal abnormalities. When multiple fibroids are present, they will usually have mostly unrelated genetic characteristics. Exact etiology is not understood; genetic predispositions, prenatal hormone exposure, and the effects of hormones, growth factors, and xenoestrogens cause fibroid growth. Known risk factors are African-American descent, nulliparity, obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, diabetes, and hypertension.

Symptoms and clinical features

Most cervical myomas are small and asymptomatic. Leiomyomas of the cervix can be subserosal, intramural, or submucous and can distort the cervical canal or upper vagina. They may produce dysuria, urgency, urethral or ureteral obstruction, pressure on the rectum, dyspareunia, or obstruction of the cervix.128 A degenerating, ulcerated or infected myoma will cause vaginal discharge.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a small cervical myoma is by inspection and palpation; it is grossly identical to the myoma of the uterine corpus. A larger cervical leiomyoma may require evaluation for surgery, usually with ultrasound. If sonographic findings are equivocal, MRI should be obtained. Because of the large field of view, and multiplanar imaging, MRI is the most accurate imaging modality in the diagnosis of cervical leiomyoma, ascertaining the size, location and the relation to the internal or external os as well as the relation to the parametrium.129

Treatment

Pedunculated leiomyomas are often removed because of their propensity to twist and infarct, bleed or prolapse. Myomectomy is indicated if the woman is symptomatic with bladder or bowel dysfunction from mechanical pressure on adjacent organs, bleeding, or dyspareunia. Excision may also be necessary for a myoma that precludes adequate evaluation of the cervix. Surgical excision of large, intramural cervical myomas is challenging because of proximity to the bladder, bowel, or ureter. Hysterectomy may be a consideration for large and symptomatic tumors; embolization is also a consideration.130

Pre-malignant and malignant lesions of the cervix

Cervical cancer and pre-cancer are well covered by other expert sources. The Colposcopy Manual is located at

http://screening.iarc.fr/colpo.php?lang=1 For diagnosis and treatment of cervical carcinoma in situ (CIN) go to the National Cancer Institute.

For cervical cancer we refer you to the World Health International Agency for Research on Cancer. The Cervical Cancer curriculum is found at cervical cancer

Sexually transmitted diseases are covered best by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Katz VL. Reproductive Anatomy. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM. Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007: 49.

- Katz VL. Reproductive Anatomy. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM. Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007: 49

- Laufer MR. Benign cervical lesions and congenital anomalies of the cervix. In: UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer, June 2023. Accessed 3-17-24.

- Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, Hendren WH. Structural abnormalities of the female reproductive tract. In: Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (Fifth Ed), Emans, SJ, Laufer, MR, Goldstein, DP (Eds), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishing Company, Philadelphia 2005: 334.

- Laufer MR. Benign cervical lesions and congenital anomalies of the cervix. In: UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer, June 2023. Accessed 3-17-24.

- Nyirjesy P. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr Infec Dis Rep. 2001; 3:540-545.

- Brunham RC, Paavonen J, Stevens CE et al. Mucopurulent cervicitis- the ignored counterpart in women of urethritis in men. N Engl J Med. 1984; 311: 1-6.

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 63-64.

- Bansal S, Bhargava A, Verma P, Khunger N, Panchal P, Joshi N. Etiology of cervicitis: Are there new agents in play? Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2022 Jul-Dec;43(2):174-178. doi: 10.4103/ijstd.ijstd_75_21. Epub 2022 Nov 17. PMID: 36743104; PMCID: PMC9890980.

- Marrazzo JM, Martin D. Management of women with cervicitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; (suppl 3):102-110.

- Taylor SN, Lensing S, Schwebke J, Lillis R, Mena LA, Nelson AL, Rinaldi A, Saylor L, McNeil L, Lee JY. Prevalence and treatment outcome of cervicitis of unknown etiology. Sex Transm Dis. 2013 May;40(5):379-85. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828bfcb1. PMID: 23588127; PMCID: PMC3868214.

- Gaydos CA, Hardick A, Hardick J, et al. Use of Gen-Probe APTIMA tests to detect multiple etiologies of urethritis and cervicitis in sexually transmitted diseases clinics [abs. C-086]; Program and abstracts of the American Society for Microbiology 106th General Meeting (Orlando, FL); Washington, DC: American Society of Microbiology. 2006.p. 63.

- Taylor SN, Lensing S, Schwebke J, Lillis R, Mena LA, Nelson AL, Rinaldi A, Saylor L, McNeil L, Lee JY. Prevalence and treatment outcome of cervicitis of unknown etiology. Sex Transm Dis. 2013 May;40(5):379-85. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828bfcb1. PMID: 23588127; PMCID: PMC3868214.

- Marrazzo JM, Martin D. Management of women with cervicitis. Clin Infect Dis 2007; (suppl 3):102-110.

- Singh V, Gupta MM, Satanarayana I, et al. Association between reproductive tract infections and cervical inflammatory changes. Sex Transm Dis. 1995; 22: 25-30.

- Eckert LO, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, et al. The inflammatory Papanicolaou smear: what does it mean? Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 86: 360-66.

- Eckert LO, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, et al. The inflammatory Papanicolaou smear: what does it mean? Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 86: 360-66.

- Long T, Long L, Chen Y, Li Y, Tuo Y, Hu Y, Xie L, He G, Zhao W, Lu X, Lin Z. Severe cervical inflammation and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;303(2):547-556. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05804-y. Epub 2020 Sep 26. PMID: 32980959.

- Bansal S, Bhargava A, Verma P, Khunger N, Panchal P, Joshi N. Etiology of cervicitis: Are there new agents in play? Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2022 Jul-Dec;43(2):174-178. doi: 10.4103/ijstd.ijstd_75_21. Epub 2022 Nov 17. PMID: 36743104; PMCID: PMC9890980.

- Nyirjesy P. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr Infec Dis Rep. 2001; 3:540-545.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2021 STI Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/chlamydia.htm

- Center for Disease Control 2021 STI Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/stdfact-gonorrhea-detailed.htm

- Lusk M, Garden F, Rawlinson W, et al. Cervicitis aetiology and case definition: a study in Australian women attending sexually transmitted infection clinics. Sex Transm Infection 2016 May; 92(3):175-81

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 64.

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 80

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 81

- Marrazzo JM, Wiesenfeld HC, Murray PJ, et al. Risk factors for cervicitis among women with bacterial vaginosis. J Inf Dis 2006; 193:619-24.

- Lusk M, Garden F, Rawlinson W, et al. Cervicitis aetiology and case definition: a study in Australian women attending sexually transmitted infection clinics. Sex Transm Infection 2016 May; 92(3):175-81

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 80

- Andersen B, Sokolowski I, Ostergaard L, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence and behavioural risk factors in the general population. Sex Transm Infect 2007; 83:237-41

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 81

- OliphantJ, Azariah S. Cervicitis: limited clinical utility for the detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in a cross-sectional study of women attending a New Zealand sexual health clinic. Sex Health 2013;10:263–7.PMID:23702105 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH12168[/efn_note 32Wiesenfeld HC, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium in women: current knowledge and research priorities for this recently emerged pathogen. J Infect Dis 2017;216(suppl_2):S389–95.

- Manhart LE, Critchlow CW, Holmes KK, et al. Mucopurulent cervicitis and Mycoplasma genitalium. J Inf Dis 2003; 187:650-57.

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 80

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 82

- Lusk M, Garden F, Rawlinson W, et al. Cervicitis aetiology and case definition: a study in Australian women attending sexually transmitted infection clinics. Sex Transm Infection 2016 May; 92(3):175-81

- McClelland RC, Sangere L, Hassan WM. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:698-702.

- Draper D, Landers D, Krohn M, Hillier S, Wiesenfeld, H, Heine R. Levels of vaginal secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor are decreased in women with lower reproductive tract infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 183:1243-8.

- CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Guidelines, 2021.

- Critchlow CW, Wolner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, et al. Determinants of cervical ectopia and of cervicitis: age, oral contraception, specific cervical infection, smoking and douching. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173:534-43

- Corey L, Wald A. Genital herpes. In: Holmes KK SP, Mardh P-A, Lemon SM, Stamm We, Piot P, Wasserheit J, eds. Sexually transmitted diseases, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999:285-312.

- Corey L, Wald A. Genital herpes. In: Holmes KK SP, Mardh P-A, Lemon SM, Stamm We, Piot P, Wasserheit J, eds. Sexually transmitted diseases, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999:285-312.

- Marrazzo J. Cervicitis. In:Basow DS (Ed). UpToDate, Waltham MA, 2015.

- Long T, Long L, Chen Y, Li Y, Tuo Y, Hu Y, Xie L, He G, Zhao W, Lu X, Lin Z. Severe cervical inflammation and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021 Feb;303(2):547-556. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05804-y. Epub 2020 Sep 26. PMID: 32980959.

- Currie MJ, Bowden FJ. The importance of chlamydial infections in obstetrics and gynaecology: an update. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 47:2-8.

- Olmsted SS, Meyn LA, Rohan LC, et al. Glycosidase and proteinase activity of anaerobic gram negative bacteria isolated from women with bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:257-61.

- Lusk M, Garden F, Rawlinson W, et al. Cervicitis aetiology and case definition: a study in Australian women attending sexually transmitted infection clinics. Sex Transm Infection 2016 May; 92(3):175-81

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2021.

- Lusk M, Garden F, Rawlinson W, et al. Cervicitis aetiology and case definition: a study in Australian women attending sexually transmitted infection clinics. Sex Transm Infection 2016 May; 92(3):175-81

- Sonnex C. Genital streptococcal infection in non-pregnant women: a case-note review. Int J STD AIDS. 2013 Jun;24(6):447-8. doi: 10.1177/0956462412472810. Epub 2013 Jul 4. PMID: 23970746.

- McGalie CE, McBride HA, McCluggage WG. Cytomegalovirus infection of the cervix: morphological observations in five cases of a possibly under-recognized condition. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57:691-4.

- Marrazzo JM, Martin D. Management of women with cervicitis. Clin Infect Dis 2007; (suppl 3):102-110.

- Nyirjesy P. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr Infec Dis Rep 2001; 3:540-545.

- Eckert LO, Lentz GM. Infections of the Lower Genital Tract. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM (Eds). Comprehensive Gynecology, 5th edition. Philadelphia, Mosby Elsevier, 2013, 582.

- Akhlaghi F, Hamedi H. Postmenopausal Tuberculosis Of The Cervix, Vagina And Vulva. The Internet Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2004 Volume 3 (1):1-3.

- Nyirjesy P. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr Infec Dis Rep. 2001; 3:540-545.

- Currie MJ, Bowden FJ. The importance of chlamydial infections in obstetrics and gynaecology: an update. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 47:2-8.

- Lusk MJ, Konecny P. Cervicitis: a review. Curr Opin Infec Dis 2008:21:40-56.

- Nyirjesy P. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr Infec Dis Rep. 2001; 3:540-545.

- Nugent RP, Hillier SL. Mucopurulent cervicitis as a predictor of Chlamydia infection and adverse pregnancy outcome. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19:198-02.

- Ovalle A, Romero R, Gomez R, et al. Antibiotic administration to patients with preterm labor and intact membranes: is there a beneficial effect in patients with endocervical inflammation? J Maternal-fetal Neonant Med 2008; 1:453-64.

- Bakken U, Skjeldestad FE, Nordbo SA. Chlamydia trachomatis infections increase the risk for ectopic pregnancy: a population-based, nested case-control study. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34:166-9.

- Center For Disease Control and Prevention 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infection Guidelines. MMWR, Recommendations and Reports, Vol 70, No.4; July 23, 2021, p 65

- Sacks SL, Griffiths PD, Corey L, Cohen C, Cunningham A, Dusheiko GM, Self S, Spruance S, Stanberry LR, Wald A, Whitley RJ. Antiviral Res. 2004 Aug;63 Suppl 1:S27-35.

- Kreiss J, Willerford DM, Hensei M, et al. Association between cervical inflammation and cervical shedding of Human Immunodeficiency Virus DNA. J Infect Dis 1994; 170:1597-1601.

- Marrazzo JM, Handsfield HH, Whittington WL. Predicting chlamydial and gonococcal cervical infection: implications for management of cervicitis. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100(3):579

- Lusk MJ, Konecny P. Cervicitis: a review. Curr Opin Infec Dis 2008:21:40-56.

- Powell AM and Nyirjesy P. Acute Cervicitis. UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer. May, 2022.

- Powell AM and Nyirjesy P. Acute Cervicitis. UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer. May, 2022.

- Center for disease control and prevention, 2021

- Critchlow CW, Wolner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, et al. Determinants of cervical ectopia and of cervicitis: age, oral contraception, specific cervical infection, smoking and douching. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173:534-43

- Marrazzo J. Cervicitis. In: Basow DS (Ed). UpToDate, Waltham MA, 2015.

- Nyirjesy P. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr Infec Dis Rep. 2001; 3:540-545.

- Dalgic H, Kuscu NK. Laser therapy in chronic cervicitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2001; 265:64-66.

- Yeung-Yue, K. Herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Dermatologic Clinics. 20(2002): 1-21.

- Yeung-Yue, K. Herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Dermatologic Clinics. 20(2002): 1-21.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59: 43-44.

- Ashley RL. Performance and use of HSV type-specific serology test kits. HERPES 2002; 9(2):38-45.

- Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted disease to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999; 75: 3-17.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59: 26.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59: 27.

- Cope LD, Lumbley S, Latimer JL, et al. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:4056.

- Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted disease to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999; 75: 3-17.

- Marrazzo, JM, Handsfield, HH. Chancroid: New developments in an old disease. In: Current Clinical Topics in Infectious Diseases, Remington, JS, Swartz, MN (Eds), Blackwell Science, Cambridge, MA 1995,129.

- Hicks CB. Chancroid. In: UpToDate, Basow DS (Ed), Waltham, MA, 2013.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59: 27.

- Lewis D. Chancroid: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Sex Transm Infect. 2002; 79:68.

- Katz VL. Benign gynecologic lesions. In:Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, eds, Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia, Mosby Elsevier, 2007: 437.

- Katz VL. Benign gynecologic lesions. In:Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, eds, Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia, Mosby Elsevier, 2007: 437.

- Goldstein DP, Laufer MR. Congenital cervical anomalies and benign cervical lesions. In: UpToDate, Basow DS (Ed), Waltham, MA, 2015.

- Insinga RP, Glass AG, Rush BB. Diagnoses and outcomes in cervical cancer screening: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 191:105.

- de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004; 324:17.

- Khan MJ, Partridge EE, Wang SS, Schiffman M. Socioeconomic status and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 among oncogenic human papillomavirus DNA-positive women with equivocal or mildly abnormal cytology. Cancer. 2005; 104:61.

- Holschneider CH. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: Definition, incidence and pathogenesis. In: UpToDate, Basow DS (Ed), Waltham, MA, 2015.

- Mao C, Hughes JP, Kiviat N, et al. Clinical findings among young women with genital human papillomavirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 188: 677.

- Khan MJ, Partridge EE, Wang SS, Schiffman M. Socioeconomic status and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 among oncogenic human papillomavirus DNA-positive women with equivocal or mildly abnormal cytology. Cancer. 2005; 104:61.

- Bosch X, Harper D. Prevention strategies of cervical cancer in the HPV vaccine era. Gynecol Oncol. 2006; 103:21.

- Farrar HK, Nedoss BR. Benign tumors of the uterine cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961; 81:124.

- Katz VL. Reproductive Anatomy. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM. Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007: 437.

- Katz VL. Reproductive Anatomy. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM. Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007: 437.

- Katz VL. Reproductive Anatomy. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM. Comprehensive Gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007: 49.

- Goldstein DP, Laufer MR. Congenital cervical anomalies and benign cervical lesions. In: UpToDate, Basow DS (Ed), Waltham, MA, 2015.