Annotation L: Exam of the hymenal ring and the pelvic floor

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationThis annotation is about gently examining the hymen as part of your systematic exam when assessing a patient for pain, dyspareunia, or any other vulvovaginal complaint, and then examining the pelvic floor, both prior to speculum exam. You will already have done pain and symptom mapping with the Q-tip test and may use the Q-tip to also assess the vestibule up to the hymen and the hymen itself. Gentle digital exam is next, first of the hymenal ring. The Q-tip touch and digital exam of the hymenal ring may take place while you are sitting in front of the patient, but you must then stand up to evaluate the pelvic floor with a lubricated finger (having already taken samples for pH, KOH, and microscopy). Keep an eye out in this annotation for links to elsewhere in the website, as topics do overlap.

The annotation also introduces you to the anatomy of the pelvic floor and its importance in diagnosing and treating some vulvovaginal complaints.

Introduction

The hymen (Latin, veil) is the anatomical doorway to the vagina, located between the vulvar vestibule and the vaginal canal. At birth, a membrane of connective tissue covered on both sides by stratified squamous epithelium, extends from the floor of the urethra to the fossa navicularis of the vestibule to partially occlude the vaginal orifice. At the interface of the introitus and the vagina, the hymen marks where the urogenital sinus (perineum) meets the vaginal canal, a mullerian structure.1

The hymen has no known anatomical or physiologic function, although prepubertal protection from infection has been hypothesized.2 Usually a thin fibrous membrane, in some women the membrane may be thicker and there may be an anatomic variant, including imperforate hymen and incomplete hymenal fenestration (e.g. microperforate, septate, and cribiform hymens). Usually there is an opening for the exit of menstrual flow. For more on the hymen and its variants, see Annotaton N; click on The hymen and its variants

After penetration, irregular petal-like remnants of the membrane (carunculae myrtiformes, Latin, little piece of flesh) may remain. With vaginal delivery, further avulsion of the hymenal remnants enlarges them to larger tags that are frequently mistaken by women as warts or other pathology. Evaluation of the hymen by inspection alone is often insufficient. If permitted by the patient, gentle palpation with the tip of the finger to feel its resistant margins gives excellent information about the integrity of the tissue. But no clinical expert can say whether vaginal penetration has occurred or not.

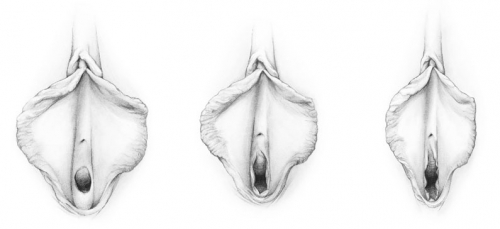

Hymen before penetration, after penetration, and after childbirth (drawing by Dawn Danby from The V Book by Elizabeth G. Stewart, MD)

Failure of the central epithelial cells of the hymenal membrane to degenerate leads to imperforate hymen,3 but the condition may also arise from an inflammatory reaction such as lichen sclerosus affecting the hymen after birth.4 Lack of elastic fibers can result in a hymen that is abnormally thick, collagenous, and resistant to intromission. Penetration, in these cases, may result in only partial rupture of the hymen with ongoing dyspareunia with further attempts at vaginal intercourse. For more on the hymen: Annotation N: click on The hymen and its variants

Exam of the hymenal ring

The hymenal ring should be visually inspected, gently moving tags and flaps of tissue with around with a Q-tip prior to insertion of the speculum exam, evaluation of the pelvic floor, or bimanual exam. Provoked or spontaneous vulvodynia may manifest as pain in the vestibule near the hymenal ring or underneath a hymenal tag necessitating cautious assessment in this area.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a careful history and an index of suspicion for hymenal abnormality.

In all cases of vulvovaginal complaints, identification of the exact location of symptoms and symptom mapping is essential. The clinician must not overlook the potential sensitivity of the vestibule or the hymenal ring before insertion of the speculum or bimanual exam. Women who have had acute or chronic dyspareunia or pain specifically in the hymenal ring, will be fearful of pain on exam. Care must be taken to perform the exam only with permission. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance for genital exam). Evaluation begins with inspection and pain mapping undertaken gently around the hymen and its tags during the vulvovaginal exam. ( Annotation I: Pain and symptom mapping, and the Q-tip test). Identification of a bulging, intact membrane at the introitus yields the diagnosis of imperforate hymen. In other cases, inspection and gentle palpation yield information on the shape and patency of the hymenal orifice, as well as its elastic or non-elastic quality. An incompletely fenestrated hymen with lack of elasticity may not admit a single digit. Scarring and strictures of the hymenal ring relating to lichen sclerosus or lichen planus will cause painful intromission and dyspareunia. In the adolescent, other signs of these dermatoses may go undetected, and this pain on penetration can be inaccurately thought to be caused by incomplete hymenal fenestration. A hymen scarred by dermatosis or altered by postpartum changes and lactational atrophy may admit one or two digits, but may be rigid and resistant to attempt to spread open the digits.

In other cases, there is no hymenal abnormality, but pain mapping shows tenderness in the vestibule at or adjacent to the hymenal ring. (Annotation K: Vulvar pain and vulvodynia ) Painful attempts at intromission may also be related to the involuntary muscle tightening called vaginismus, which may lead to extreme fear of pelvic exams or penetrative sex. Annotation D: Patient tolerance for genital exam and Pelvic floor dysfunction/vaginismus

Examination alone is insufficient to permit a conclusion that a hymen is intact. Medico-legal considerations are beyond the scope of this educational material.

More comprehensive information on the hymen and its variants is found in Annotation N; click on Hymenal variants in the menu.

Treatment

Imperforate hymen or incomplete hymenal fenestration, see Annotaton N; click on hymenal variants

Postpartum changes and lactational vulvovaginal atrophy

Reassurance that a return to normalcy will occur as lactation diminishes or on return of the menses may be sufficient. Treatment with a small amount of topical estrogen cream to the vestibule and hymenal ring twice a week may be helpful. Use of topical lidocaine prior to penetrative sex may also be helpful.

Stricture of the hymenal ring related to inflammation of lichen sclerosus or lichen planus

A scarred hymenal ring may be slowly dilated with progressive dilator use with lidocaine; perineoplasty with vaginal advancement may be required. (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders: click on LS or LP). Ongoing control of the inflammation of lichen sclerosis or lichen planus is with topical steroids is important.

Pelvic floor dysfunction/vaginismus

It is essential to recognize that dyspareunia may not resolve after hymenectomy until high tone pelvic floor dysfunction from pelvic floor muscle tightening in response to the pain is addressed with physical therapy for the pelvic floor. Hymenectomy is not the treatment for vaginismus. Please see: Vaginismus/Pelvic floor dysfunction.

The pelvic floor

The pelvic floor is a complex structure of 14 intricate, inter-related muscles and ligaments, intertwined with nerves, surrounded by connective fascia attached to the bony pelvis and pelvic organs. From this prosaic assembly come astonishing functions: facilitation of urination and defecation while maintaining continence, key roles in sexual function and in labor and delivery, and to the extensive fibroelastic network in the fat that contains anatomical spaces. Because the pelvic muscles relate to more than one organ system, their dysfunction can impact multiple systems at the same time, and each system can be a potential source of pain and other symptoms. Pain commonly attributed to painful end-organs such as the bladder, bowel and external genitalia may arise from high-tone pelvic muscle dysfunction manifesting as urinary urgency, constipation, dyspareunia, and neurogenic inflammation of the bladder.5 It is often inaccurately called vulvodynia.

The clinical importance of the muscles of the pelvic floor (PFM) far exceeds the clarity and accuracy of most descriptions of pelvic floor anatomy. Almost no other region of the body is so commonly described in unhelpful generalizations, confusing and overlapping terminology, and misleading metaphor, resulting in real obstacles to understanding the pelvic organ support system and the role of the pelvic floor muscles within that system. The emergence of vulvodynia as a chronic pain condition illuminated the need to understand the PFM; recent MRI studies have likewise begun to elucidate much of the mystery related to the PFM.6

Please review this excellent video for a clear understanding of the anatomy of the pelvic floor:

http://anatomyzone.com/tutorials/musculosketetal/pelvic-floor

Reproduced with permission. Dr Peter de Souza. Anatomyzone.com

Accurate diagnosis of pelvic floor muscle (PFM) disorders requires comprehensive knowledge of the musculoskeletal (MSK) components of the pelvis and surrounding structures. Regarded often as only a single, muscular layer (the pelvic diaphragm or levator ani), the pelvic floor, in actuality is composed of multiple layers. From superior to inferior, these are the endopelvic fascia, the muscular pelvic diaphragm (the levator ani), the perineal membrane (urogenital diaphragm), and a superficial layer of muscles (bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus). The nerve supply to the pelvic floor and related organs is via branches of the sacral plexus: the pudendal nerve arises from the second, third and fourth sacral nerves and courses inferior to the pelvic floor; the levator ani nerve originates from the third sacral spinal nerve and courses superior to the pelvic floor and the parasympathetic pelvic splanchnic nerves. The sympathetic supply is by the hypogastric nerve. Higher regulating levels of the central nervous system (e.g., pontine micturition center, cerebral cortex) are crucial for proper function of the pelvic floor.7

The levator ani muscles are the most important muscles in the pelvic floor, with several muscle components: the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus. These are separate muscles that meet in the midline to form a muscular sheet, the pelvic diaphragm, across most of the floor of the pelvis. This diaphragm is perforated by an opening for the vagina and urethra (urogenital hiatus) and an opening for the rectum (anal hiatus).8

The most anterior (medial) fibers of the pubococcygeus that meet bilaterally at the perineal body superior to the anus, are called the pubovaginalis. These act as an important sphincter of the vagina. Vaginal closure is assisted by the bulbospongiosus and puborectalis muscles. These muscles also activate the elevator to facilitate vaginal ballooning. The most posterior fibers of the pubococcygeus (puborectalis) form a sling around the rectum.9 They attach to the tip of the coccyx at the anococcygeal body.10

The posterior portion of the levators, the iliococcygeus muscle, anchors above the tendinous arch of the levator ani and to the spine of the ischium posteriorly. The tendinous arch of the levator anchors to the spine of the ischium posteriorly and to the pubic bone or the obturator membrane anteriorly. The arch attaches to the covering fascia of the obturator internus muscle so that the levator covers the lower portion of the obturator internus muscle and all of the obturator foramen. Although the obturator muscle is not considered a PFM per se, it has fascial connections to the PFMs, via the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, which create anatomic and functional synergy. It is important to understand that the obturator has a significant effect on pelvic floor function secondary to this direct connection. When the length of the obturator internus is altered because of overactivity, spasm, or tension, it can create tension on the levator ani, creating suboptimal functional ability of the levator ani. In addition, the obturator internus assists in hip external rotation and abduction. 11

The shelf-like triangular coccygeus muscle forms the posterior part of the pelvic diaphragm. The coccygeus is not part of the levator ani, having a different function and origin. It originates at the ischial spine and courses along the posterior margin of the internal obturator muscle. The muscle inserts at the lateral side of the coccyx and the lowest part of the sacrum. The sacrospinous ligament is at the posterior edge of the coccygeus muscle and is fused with this muscle. The proportions of the muscular and ligamentous parts may vary. The coccygeus muscle is innervated by the third and fourth sacral spinal nerves on its superior surface.12

The constant muscle tone of the levator ani and coccygeus muscle prevents the ligaments from becoming over-stretched and damaged by continuous tension.13

The muscle tone combined with the stability of the fascia results in a dome-shaped form of the pelvic floor (in the coronal plane) and closes the urogenital hiatus, a U-shaped defect in the muscles in the urogenital triangle that allows the passage of the urethra and vagina. During vaginal delivery, the levator ani muscle is substantially stretched and injury may occur, often near the pubic bone insertion.14

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is a common condition with a reported prevalence in women of up to 27%.15 PFMs that are unable to voluntarily contract when appropriate are considered underactive. Underactive PFMs leading to urinary incontinence are reported in 25% of young women, 44-57% in middle-aged and postmenopausal women, and 75% in older women.16 Weakness of the endopelvic fascia is the main factor in the etiology of pelvic organ prolapse, also very common in older women.17 Overactive PFMs have an inability to relax or may even contract when relaxation is functionally required (i.e., during urination or defecation).18 In a retrospective study of 238 women with complaints of urination, defecation, and/or sexual problems 77.2% had measurable pelvic floor dysfunction. Pelvic pain, a frequent symptom of overactive PFMs, encompasses a number of diagnoses with a prevalence range of 3.8-24%19 The reported prevalence of MSK disorders and pelvic floor myofascial pain associated with chronic pelvic pain varies from 21% to 85%.20 Always essential is recognition that there may not be a single source of dysfunction. Urinary urgency and frequency accompanied by other visceral symptoms (i.e., chronic constipation, painful bladder syndrome), often are attributed solely to the end organ, thus ignoring possible PFD as part of the differential diagnosis.21

While we know that pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) is associated with vulvodynia, the pathophysiological processes are not fully understood. It is likely that musculoskeletal dysfunction could arise by several different mechanisms, as indicated in the table below.22

Table L-1 Possible causes of vulvovaginal pain from specific disorders (and associated links to information in this website)

| Candida vaginitis (P) | Cellulitis (Atlas of vulvar disorders) |

| Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) (P) | Systemic diseases, e.g., Crohn (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) Sjögren (O) |

| STIs: trichomonas (P), herpes (Herpes simplex), chancroid (Atlas of vulvar disorders ) | Fistulas (N) |

| Hypo Estrogenization (genitourinary syndrome of menopause or lactational atrophy), inadequate lubrication (P) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Drug reaction (O) |

| Irritants and allergens, irritant or contact dermatitis (J)(H) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Congenital anomalies (imperforate hymen (N), vaginal septum) (N) |

| Dermatoses with erosions, fissures (e.g. lichen sclerosus, lichen planus) (H) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Squamous cell carcinoma, other cancer and treatment for cancer, (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders), Extramammary Paget Disease (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

| Dermatoses with ulcers (e.g. aphthous ulcers, pemphigus, pemphigoid) (H) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Semen allergy (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

| Plasma cell vulvitis (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Pudendal nerve compression or neuroma (K) |

| Trauma (obstetrical, female genital cutting) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Iatrogenic (post-op, post radiation or chemotherapy) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

| Psychosexual issues leading to poor sexual arousal, vaginismus (D) (Vulvovaginal pain and sexuality) | Vulvovaginal neoplasia (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

Note: It is always possible that there may be more than one condition present at the same time.

Biomechanical factors

Biomechanical origins are a common source of pelvic floor dysfunction and pain. Traumatic vaginal delivery by forceps or vacuum extraction is an important factor.23 Injury to the levators is widely regarded as a source of stress urinary incontinence, vaginismus, vulvar pain, urinary frequency, and ongoing dysfunctional voiding after delivery.24 Labral tear, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, motor discoordination, overuse, repetitive strain, chronic constipation/strain, and compression from pudendal nerve entrapment are other possible biomechanical causes.

Sexual and emotional abuse

Recent case-controlled studies reporting vaginismus or dyspareunia outcomes in individuals with or without a history of abuse were reviewed to discern the relationship of abuse history with vaginismus and dyspareunia diagnosis. A significant relationship was found between a history of sexual (1.55 OR; 95% CI, 1.14-2.10; 12 studies) and emotional abuse (1.89 OR; 95% CI, 1.24-2.88; 3 studies) and the diagnosis of vaginismus. No statistically significant relationship was observed between physical abuse, vaginismus, and dyspareunia. No significant difference was found between sexual or physical abuse in terms of assessment methods for the diagnosis of vaginismus and dyspareunia. Experience of sexual abuse in childhood or adulthood has been reported as one of the primary risk factors connected with the development of sexual dysfunction. The fact that many studies largely ignore the existence of child abuse has been criticized.25

Surgical history

Vaginal surgery such as sacrospinous vault suspension or transvaginal tape placement may affect the pudendal nerve and the levators, leading to post-operative voiding dysfunction, urinary frequency, urgency, and pain.

Viscerosomatic factors

Pelvic pain can be visceral (gynecologic disease, irritable bowel syndrome, vaginal or urinary tract infections) or somatic (PFM) in origin. Interactions between visceral and somatic neural stimuli can be complex and confusing for patients and practitioners alike. Stress urinary and fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and pain often have both visceral and somatic components.26

Pelvic floor holding behaviors

Dysfunctional pelvic floor behavioral practices originating in childhood can persist into adulthood; control of the pelvic floor begins with toilet training. Some children develop hyper-vigilance, holding of urine, and inability to relax to void. Recurrent urinary tract infection, urinary retention, and vesicoureteral reflux with high tone pelvic floor dysfunction can follow. Similarly, constipation and incomplete emptying of the bowel also influence pelvic floor hypertonicity: delaying voiding and/or stool evacuation, hovering vs sitting on a toilet seat, stress-induced pelvic floor tightening on a diurnal basis.27

Adult dysfunctional disorders

Urinary holding patterns related to job demands that preclude regular voiding in adults may lead to dysfunction of the pelvic floor. Abnormal postural positions, or postural abnormalities such as differential in leg length, gait abnormality, or pelvic girdle abnormality, may also lead to hypertonicity and pain. It is often the passage of time, or a trigger such as the demands of pregnancy and delivery, that lead to symptom development. Prolonged lack of motion such as long car rides is another source of possible pelvic floor disability. Severe anxiety disorders and a history of sexual abuse can also contribute to such disorders.28 If these childhood or adult dysfunctions are not considered in the evaluation of dyspareunia, vulvovaginal symptoms and pelvic pain, the hypertonic pelvic floor may not be addressed, and the problems will persist.

Scar tissue

Scar tissue consists of fibrous tissue that replaces normal tissue after some type of injury such as pelvic surgery, childbirth, an injury, or repeated abscess of the Bartholin gland. Lichen sclerosus and lichen planus are other sources of scarring on the vulva. Scar tissue can adhere to skin, connective tissue, or muscle, pulling on neighboring tissue and making the area tight, with restricted blood flow leading to pain. Nearby nerve tissue can also be affected, resulting in pain in that area or pain referred to a more distant site. Scar tissue also causes functional loss in the affected tissue such as the anal sphincter. The sphincter loses some of its ability to contract, leading to loss of control over bowel function.

Hormonal influence

The association between vulvodynia and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/PBS) may involve sex hormone-dependent mechanisms regulating vulvovaginal health. In one study, a significant positive effect of local vaginal estrogen therapy (thrice weekly estriol 0.5 mg cream) after 12 weeks was evident on urinary and sexual function. The association between vulvar pain and bladder pain could be related to a vaginal environment carrying signs of hypoestrogenism. 29

Trigger points

Muscles are composed of fibers that either overlap to contract (shorten) the muscle or pull apart to stretch (lengthen) the muscle. When muscles become too tight, and associated loose connective tissue thickens, blood flow becomes restricted, with less oxygen reaching the tissue. Anoxia causes pain. In addition, muscles become too short because the fibers start to overlap too much (as with clenching, tightening in response to pain), or too long because the fibers pull too far apart (with pushing during childbirth or constipation). The muscle fibers then become vulnerable to the development of trigger points (TrP), small, hyper-irritable patches of painful, involuntarily contracted muscle fibers which refer pain to other areas. This pathophysiology has been known for many years.30

TrPs can also interfere with proprioceptive, nociceptive, and autonomic functions of the affected area. Muscles containing TrPs are shortened, with limited range of motion, weakness, and hypertonicity. Loss of coordination is a presenting symptom. TrPs typically occur in muscle as a result of trauma, repetitive overuse, or inflammation.31 Trigger points of muscle fibers frequently go unrecognized until a skilled practitioner locates them and recreates the patient’s pain symptoms.

The intimate relationship between the pelvic organs and the soft tissue surrounding them is also a factor in pain. If any of the organs is inflamed, (such as the bladder during a urinary tract infection), pain from the inflamed organ can be referred to the surrounding neuromuscular tissue: the pelvic floor muscles and nerves, the abdominal muscles, and even the skin of the vulva. With ongoing inflammation, nearby muscles tighten painfully. This impaired tissue can affect other nearby organs, such as the urethra or rectum, creating further symptoms of gastrointestinal distress, thereby creating pain on pain.32 The mechanism of this pain closely resembles the nociception of vulvodynia, described below and discussed in detail in https://vulvovaginaldisorders.org/vulvar-pain-and-vulvodynia/

With trauma, such as overt injury, overuse, or misuse to a muscle fiber, a cascade of inflammatory mediators (bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, prostaglandins, adenosine triphosphate) released around the injured fiber sensitizes muscle nociceptors and reduces their mechanical threshold. This sensitivity results in a “hair-trigger” response of the muscle, resulting in muscle hyperalgesia (muscle pain) and mechanical allodynia (pain from muscle movement that should normally not cause pain). Normal muscle contraction is therefore perceived as painful. This process produces peripheral sensitization. Central sensitization in the brain and spinal cord can follow. Because of prolonged noxious stimuli, a series of neuroplastic changes occur in the central nervous system. Pain impulses are amplified because of biochemical and neuroinflammatory changes in the spinal cord. Generation of spontaneous pain impulses occurs, and there is expansion of the area of perceived pain. Non-noxious stimuli start to be perceived as painful.33 Sensitization means that the whole pain process volume is turned up too high.

The upregulation described above has received attention mainly in relation to neuropathic pain. Animal studies promote awareness that deep myofascial pain is actually more effective in the induction of central sensitization than is peripheral pain.34

Symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction typically involve the pelvic organs that are controlled by the pelvic floor. Bladder symptoms may exist, such as voiding dysfunction, post void pain, urethral pain, hesitancy or the constant or exaggerated urge to void. Colorectal symptoms may be present including constipation, obstructed defecation, painful defecation, or sharp rectal pain (proctalgia fugax). Vulvovaginal pain, burning, stinging, pain on touch in the vestibule with dyspareunia, and vaginismus may be complaints. Intercourse may not be painful at the time, but may lead to post-coital pain for 12 to 48 hours after intercourse. This is a common complaint with pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction, as are clitoral pain and pain with orgasm.

The pain symptoms are often vague and poorly localized. Pain may be described as burning, aching, or throbbing, and as having a quality of pressure or heaviness. Prolapse may come to mind, but the leading edge of prolapse must be at the level of the introitus to produce any symptoms.

Women may describe the pain as vaginal, rectal, suprapubic, or in either or both lower abdomincal quadrants, wondering if this is pain from an ovarian cyst. They are often treated repeatedly for urinary tract infection with negative cultures. They also report radiation into the hip and back. Almost all women say that the pain is worse as the day progresses and is typically exacerbated by pelvic floor muscle activities such as sitting, walking, exercise, intercourse, voiding, or bowel movement.

Annotations A-E provide a wealth of information necessary to make a new trusting friend and an accurate diagnosis. Included are details necessary to obtain a clear picture, critical history questions to ask, suggestions to ease the way, and guides for avoiding pitfalls. Your patient is a professional; she has often seen many medical experts, and packs a cache of disappointments. She wants you to understand her story and become her partner in deducing the best management.

Annotation A has a trove of signs and symptoms associated with vulvovaginal disorders.

Annotation B shapes the make or break history which may need more than one visit to complete.

Annotation C suggests non- genital areas to examine in search of signs associated with vulvovaginal disorders.

Annotation D includes pitfalls to avoid so that you build trust.

Annotation E Provides the detailed, systematic vulvovaginal examination.

Although pelvic examinations routinely include the evaluations of the reproductive organs, PFM examination is not part of most clinicians’ pelvic examinations. Often it is omitted.35 It is important to learn this skill to become expert in vulvovaginal assessment and diagnosis and it is important to refer to pelvic floor physical therapist experts as necessary.

Also important to remember: proceeding with the exam without informed consent risks significant psychological trauma and increased physical pain. Providing a detailed description of the examination and its components and why these are necessary before the assessment will help decrease stress and anxiety. Indicating that the exam will be halted instantly if the patient says so, helps with trust. A support person may provide reassurance.

A gentle approach is mandatory, not only for patient comfort, but also for accurate findings from the examination. In anticipation of pain, the internal digital evaluation of pelvic structures is suggested before or instead of speculum examination. Speculum insertion often exacerbates and/or triggers PFM overactivity. Avoidance of stirrups if possible is a prudent decision, with use of the simple supine position, with both hips and knees flexed, and feet on the examination table, comfortably placed hip-width apart.36

Palpation should take place with the pad of the finger to prevent direct pressure with the tip of the finger or fingernail. To reduce anxiety regarding the degree of pressure used, the practitioner can apply equal pressure to the thigh of the patient, demonstrating the degree of pressure used with the internal palpating finger. The examination is performed with the greatest accuracy while being mindful of the patient’s comfort and tolerance of the examination. The intention is to evaluate and assess the musculature and surrounding tissue on the outside of, and at the entrance of the vagina. Also evaluated are the deep muscles, and connective tissue (fascia), as well as the internal organs. 37

The superficial PFM include the bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial perineal muscles. Locating these small muscles is easiest when using a superimposed imaginary clock on the vulva. The clitoris represents 12 o’clock; the left or right ischial tuberosity 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock, and the anus 6 o’clock.To locate the ischiocavernosus, palpate from 1-2 o’clock or at 10-11 o’clock over the labia majora. The bulbocavernosus is palpated around the perimeter of the introitus. Palpation of the superficial transverse perineal muscle begins at 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock and continues to the perineal body where the bilateral muscles attach.38

The muscles in this group often can be overactive, restricted in mobility, and tender when palpated. Pain with gentle palpation at 1 o’clock and 2 o’clock or 10 o’clock and 11 o’clock over the labia majora is indicative of ischiocavernosus muscle overactivity. Tenderness along 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock suggests dysfunction in the superficial transverse perineal musculature. Overactivity of the bulbocavernosus can cause tenderness around the vaginal opening and contribute to dyspareunia. Pain with gentle pressure at any of these locations helps determine if superficial MSK dysfunction (or myofascial pain) is present. Recognition is important because it helps determine the vigor of the rest of the examination.39

The deep pelvic floor muscle layer, or levator ani, is palpated lateral to the midline at 5 o’clock or 7 o’clock by gently inserting the assessing finger 1-2 knuckles (2-4cm) into the vagina past the superficial muscles. Once inside the vaginal canal, palpation at 6 o’clock is the anal sphincter and rectum (2-3 finger widths). The coccygeus can be palpated by locating the coccyx, behind the rectum, and palpating on either side, following the muscle laterally to the ischial spine. Because of the interplay between pelvic floor and hip muscles, assessment of the obturator internus muscle is included in the internal examination. The right obturator internus is located by moving the assessing digit laterally within the vaginal canal to 9 o’clock and 10 o’clock. Obturator internus function is evaluated by palpating its active contraction. To accomplish this, place a hand on the outside of the flexed knee on the same side as the assessing digit. Ask the patient to gently push the knee outward (hip external rotation/abduction) while resisting any active motion with the hand on the knee. This will produce a palpable obturator internus contraction that will gently rise into the assessing finger. Likewise, palpation at 2 o’clock and 3 o’clock will evaluate the left obturator internus. The puborectalis and periurethral tissue can be found by moving the palpating finger further anterior and superior to 11 o’clock or 1 o’clock, halfway between the obturator internus and the pubic symphysis. To continue the examination, turn the examining digit over (palm facing up). The finger pad is used to palpate the urethra and inferior aspect of the bladder at 12 o’clock, posterior to the pubic symphysis. Palpation of urethra and bladder tissue is similar in feel to that in the rectum, only narrower.

Pain or tenderness with palpation indicates possible muscle overactivity and/or trigger points. Progress slowly and explain that you will be palpating muscles that lie both on the sides and bottom of the vaginal canal. Active trigger points (Table L-2 below) throughout the broad fibers of the levator ani can create discomfort and referred pain when palpated, whereas underactive PFMs will feel softer, less bulky, and usually not painful. Abnormal rectal tension is palpated as firm roundness, which can reproduce pain or urgency for flatulence or defecation; however, that same roundness when asymptomatic may suggest a rectum full of stool.40

Palpation of the superficial transverse perineal muscle begins at 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock and continues to the perineal body where the bilateral muscles attach.41 Abnormal tension in the urethra, periurethral fascia, and bladder can cause pain or urinary urgency when assessed.42

Palpation of overactive PFMs tends to feel bulkier and thicker and typically creates or elevates tenderness, discomfort, or pain. Palpation also has the ability to cause referred pain to other regions throughout the pelvis, hips, and back. Documentation of the presence or absence of pain with palpation is sufficient to substantiate or rule out PFM and visceral involvement in the differential diagnosis. Description of pain (burning, aching, tingling) can be beneficial in understanding and communicating symptoms.43 The majority of studies describing pelvic floor pain assessments use the numeric rating scale (0-10); however, recording pain as “absent/pressure” (0), “mild (1-3), ” “moderate”(4-6), or “severe”(7-10)44 can be sufficient in communicating with the patient and for referral to PT. Always keep in mind that factors such as pain beliefs, catastrophizing, and pain interference can all affect how patients rate their pain.45

Physical therapy to the pelvic floor

The small number of studies applying both pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) and mindfulness to chronic pelvic pain (CPP) suggests that a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to treat women with CPP; it follows that further studies involving these therapeutic techniques are necessary. 46 Accompanied by CBT and psychosocial support, physical therapy has become an integral part of a multidisciplinary team approach in the treatment of many forms of vulvovaginal pain and pelvic floor dysfunction.

Broadly, pelvic floor muscle therapy (PFMT) works through strengthening pelvic muscles, promoting pelvic floor support, and increasing pelvic muscle volume. PFMT also leads to elevation of the levator plate, giving rise to increased structural support. The therapeutic efficacy thus relies on both passive (bulking, tone, support) and active (timed voluntary contractions or relaxations) mechanisms. 47

As the PT referral is made, it is essential to emphasize that this is not conventional sports injury PT. Upon hearing PT mentioned, a woman who never heard of a pelvic floor muscle in her life, immediately thinks of repetitive exercises to an injured arm or leg and is unable to understand how this could possibly improve vulvar pain and dyspareunia. She does not go to the physical therapist. She therefore loses weeks of therapy until she presents, unimproved, at the next visit.

Manual therapy techniques

Physical therapists use their hands to identify and treat tissue restrictions or adhesions. Massage, myofascial release, trigger point release and stretching: all can diminish the movement of skin, connective tissue, and/or muscle leading to limitations in posture and range of motion. With advanced training, therapists employ these skills not only to external structures such as the low back or hip, but also to internal pelvic structures. Though the pelvic muscles are an integral part of pelvic function, they are influenced by the structures within the pelvic bowl (viscera, urethra, bladder, uterus, rectum, and anus), ligaments and fascia. Appropriate treatment addresses abnormalities, allowing rehabilitation of the pelvic floor muscles in these organs and tissue.48.

Identification and treatment of trigger points

Dyspareunia, bladder and bowel dysfunction may represent an outcome from pelvic floor muscle TrPs. Pain arising from a trigger point can be very misleading since the knot of taut muscles refers pain elsewhere. Table L-2 describes the location of referred pelvic floor muscle pain.

Table L-2 Myofascial Trigger Point Referral Patterns 49

| Muscle | Referral Pattern |

| Rectus abdominis | Mid and low back and viscerosomatic symptoms |

| Iliopsoas | Paravertebral and anterior thigh |

| Quadratus lumborum | Iliac crest, outer thigh, buttock |

| Gluteus maximus | Sacrum, coccyx, buttock |

| Gluteus medius | Low back, sacrum, buttock, lateral hip/thigh |

| Adductors | Groin and inner thigh |

| Hamstrings | Gluteal fold, posterior thigh, popliteal fossa |

| Piriformis | Low back, buttock, posterior thigh |

| Obturator internus | Coccyx and posterior thigh, fullness in rectum or vaginal pain |

| Coccygeus | Coccyx, sacrum, rectum |

| Pubococcygeus | Coccyx, sacrum, rectum |

| Iliococcygeus | Coccyx, sacrum, rectum |

| Ischiocavernosus | Perineal aching |

| Bulbospongiosus | Dyspareunia, perineal pain with sitting |

| Transverse perineum | Dyspareunia |

| External anal sphincter | Diffuse ache, pain with bowel movements, constipation |

| Urinary sphincter | Urinary retention, perineal urge, frequency |

Highly variable symptoms may include sharp, dull, achy, or deep pain.50. Manual therapies to eliminate TrPs include skin rolling (moving each layer of tissue over another-skin, fascia, and muscle); strumming (rubbing across muscle fibers to compress tissue), and stripping (release parallel to muscle fibers). Physical therapists also use dry needling- placing a fine needle into the TrPs, using rapid in-and-out maneuvers. A few studies have shown that the dry needling technique is as effective as local injection of anesthetics.51

Saline, corticosteroids, a variety of local anesthetics including lidocaine and bupivacaine, botulinum toxin serotype A (BoNT-A), have all been used and studied in attempting to subdue TrPs..52.

Stimulation of the local twitch response in direct needling of the TrP is valuable in achieving immediate effect.There is good evidence to suggest that there is no advantage of one injection therapy over another, or of any drug injectate over dry needling.Their review also suggested that pain reduction with saline TPI is equal to pain reduction with local anesthetic TPI, both being significant.

Although adding corticosteroid preparation to local anesthetic is a common practice, it has not been reliably shown to reduce pain more than TPI with local anesthetic alone.

Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) produces sustained and prolonged relaxation of muscles by inhibiting release of acetylcholine at the motor endplate and is itself an analgesic inhibiting central sensitization. Commercially prepared BoNT-A is expensive and should be used with care by a well-trained physician. Despite the widespread presence of TPI for myofascial pain, there is no consensus regarding the number of injection points, frequency of administration, and volume or type of injectate. Controlled studies are needed to evaluate the comparative efficacy of TPIs and their potential benefits in long-term pain reduction, if any.

Myofascial and myofascial trigger point release

Myofascial release is a manual therapy technique using light stretch to stimulate increased blood flow, thereby restoring myofascial mobility, tissue hydration, and muscle length. Women’s Health physical therapists have successfully utilized the technique to treat vulvodynia, interstitial cystitis, and dyspareunia. 96% of women’s health physical therapists use soft tissue mobilization and myofascial release to treat women with localized provoked vulvodynia (LPV/PVD).

The myofascial system is a slightly mobile, continuous, laminate sheath of connective tissue covering all the visceral and somatic structures of the body. It is located both superficially and deep, permitting tissue mobility. It also covers visceral organs, muscles, bones and nerves. In a healthy woman, strength and mobility are largely governed by myofascial control. Following trauma, longstanding poor posture, scarring or inflammation, the fascial system may be restricted and adherent, thus decreasing flexibility and stability leading to chronic pain.53.

Myofascial TrPs can also interfere with proprioceptive, nociceptive, and autonomic functions of the affected area. Muscles containing TrPs are shortened, with limited range of motion typically occur in muscle as a result of trauma, repetitive overuse, or inflammation.54 Trigger points of muscle fibers frequently go unrecognized until a skilled practitioner locates them and recreates the patient’s pain symptoms.

Surface electromyography and biofeedback

The use of surface EMG (sEMG)–assisted biofeedback muscle retraining can decrease pelvic floor muscle tone, decrease muscle responsiveness to pain, and improve flexibility and relaxation. Biofeedback, and electrical stimulation can also be effective in reducing pelvic floor muscle dysfunction.55 Biofeedback is an evaluative and therapeutic technique in which information about a normal physiological process is presented to the patient via subconscious methods and/or via a therapist (or machine) who offers a visual, auditory, or tactile cue. In the case of pelvic floor disorders causing pain or disability, muscle activity is measured by means of the electromyograph (EMG), which detects the electrical potential generated by muscle cells when active or at rest, recording their signals. Surface electrodes on a small probe inserted into the vagina or the anus detect the activity of the pelvic floor muscles and display the EMG on a computer monitor screen. A woman who can visualize the activity of her pelvic floor muscles may be aided in improving control and recovery following contraction and normalize muscle activity. Thus, biofeedback has been widely used in treatment of pelvic floor dysfunctions, mainly by promoting patient learning about muscle contraction. When asked to tighten her muscles, she can see a measurement of how well she is doing. When asked to release her muscles, she watches as the EMG activity lessens.56

Vaginal Dilators

Vaginal dilators are an important part of the desensitization from pain process. Dilator use requires teaching, how-to demonstration to the patient, and return demonstration to the clinician. Without the experience in the office, often not possible at a first visit, a woman is unlikely to use a set of dilators. Dilators are not used to “dilate” or open the vagina. The smooth, rounded rods in graduated sizes are inserted by the woman in the privacy of her home, on a planned schedule, to enable her to feel safe and in control while learning what size object she can insert without pain, only as tolerated. Use of dilators for desensitization is most successful when accompanied by pelvic floor physical therapy.

Therapeutic exercises

Spinal Stabilization

Recently, physical therapists have focused on the neuromuscular mechanisms underlying lumbo-pelvic dysfunction, low back pain, and pelvic pain. Data suggest that lumbopelvic dysfunction arises from altered motor control between the larger support musculature (e.g., erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, rectus abdominis, gluteals) and the weaker, smaller trunk stabilizers (also known as the core structures– abdominis, pelvic floor, and multitidus muscles) and the respiratory diaphragm. This focus led to the concept of “core stabilization.” The core stabilization goal is to renew the balance and strength at the body’s pelvic base. Women with PFD often experience weakness and imbalance throughout their core structures. Pelvic and abdominal dysfunction, including increased tone and/or weakness and/or a diastasis rectus (separation of the right and left rectus abdominus muscles can cause core instability and dysfunctional postures). Faulty postures are those positions that increase stress to joints and use excessive muscle activity. A dysfunctional posture can result in the formation of muscle TrPs, hypertonicity, and pelvic pain. Therapeutic exercises should address these musculoskeletal abnormalities by including strengthening and lengthening where indicated, postural corrections, diastasis recti corrections and pelvic floor muscle retraining. Specific examples of core exercises include, but are not limited to transvers abdominis isometric contractions, pelvic tilts, oblique crunches, bridging quadruped with opposite arm and leg raise, hip external rotation exercises, squats, pelvic floor muscle exercises and plank positioning.57

Pelvic floor muscle retraining

Pelvic floor muscle retraining involves the active renewal of neuromuscular control, and may include strengthening of muscular weakness, down-training of muscular tension, and re-coordinating of overall muscular control. A major portion of the research on pelvic floor muscle retraining has involved treatment approaches for incontinence rather than vulvar pain or dyspareunia. Data have long demonstrated success with treating pelvic pain and PFD without the use of biofeedback. 58 When reviewing the PT therapy approach to women with chronic pelvic tension, one can see that manual techniques (contract/relax, reciprocal inhibition, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) augment the process of pelvic floor retraining. This can be partly explained by the work of Morin et al., indicating that there are greater pelvic floor muscle resting forces and stiffness, and an increased active component in women with LPV/PVD when compared to controls.59

Adjuvant treatment with medications and physical therapy

Topical lidocaine

Topical lidocaine 2-5% gel, ointment, or cream is often prescribed for women with vulvodynia in order to reduce mucosal pain sensitivity and desensitize the vestibular nerves. In clinical practice, lidocaine may be used several times per day when needed. A double-blinded RCT, however, revealed no difference in pain response to the tampon test (pain on insertion or removal of a tampon) in women with PVD who received topical lidocaine compared with those who received placebo; (each applied the topical four times daily). The same investigators reported a greater benefit with PFPT than with overnight topical lidocaine use.60 In a 2019 uncontrolled cohort study of women with provoked vulvodynia, the usage of nightly 5% lidocaine ointment showed a reduction of visual analog intercourse-related pain and daily pain scores.61 Well designed recent studies appear to favor the use of intermittent lidocaine to benefit women with intense vestibular pain on touch.

Topical amitriptyline

Traditionally, vulvodynia with PFD was treated with both topical and oral medications, in combination or alone. The main indication for topical treatment is provoked localized vulvodynia. In a prospective study with 150 patients, amitriptyline 2% cream has shown to have a 56% response rate in patients with entry dyspareunia, and 10% of patients achieved a pain-free status. In a retrospective study with 38 patients, amitriptyline 2% with baclofen 2% cream demonstrated a lower level of pain with intercourse in patients with vulvodynia.62

Oral antidepressants and anticonvulsants

Oral medications used commonly for chronic pain conditions and in the recent past for provoked vulvodynia, include tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants. Amitriptyline was the most commonly used tricyclic antidepressant, usually started at 10 to 25 mg daily, with gradually increasing doses up to 150 mg/d. Tricyclic antidepressants act by modifying pain centrally at the level of the dorsal horn. Efficacy of these drugs has been unclear because there are few well-designed trials regarding its use. However, a well-designed randomized placebo-controlled trial showed no improvement with the use of another tricyclic antidepressant, desipramine, over the use of placebo.63 Two other prospective trials investigating antidepressant use in the treatment of vulvodynia also showed no benefit relative to comparison groups.

Gabapentin has been the most commonly prescribed anticonvulsant for many chronic pain conditions, including vulvodynia. It affects voltage gated sodium channel function at nerve terminal, attenuating depolarization and the release of pain-promoting neurotransmitters glutamate and substance P.64 The anticonvulsant had never had formal study in relation to sexual function until a 2019 multicenter double-blind, randomized crossover trial; sexual function, measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), was evaluated with gabapentin (1200 – 3000 mg/day) compared to placebo. Pain free controls, matched by age and race, also completed FSFI for comparison. Gabapentin improved sexual function in this group of women with provoked vulvodynia. But sexual function overall remained lower than in healthy women without pain. The domain of arousal showed the most statistically significant increase in the Female Sexual Function Index, suggesting a central mechanism of response. Women with median algometer pain scores greater than 5 improved sexual function overall, but the improvement was more frequent in the pain domain. The authors believe that gabapentin may be effective as a pharmacologic treatment for those women with provoked vulvodynia and increased pelvic muscle pain on exam.65 Gabapentin is usually started at a dose of 300 mg/d and increased every 3 days up to a dose of 3600 mg/d. Side effects include sedation and mental status changes, although these are not usually so dramatic as to preclude its use.

Muscle relaxants

There is a paucity of information about the use of pelvic floor muscle relaxants to treat vulvodynia, although they have been utilized for hypertonic pelvic floor muscle dysfunction over the past ten years. Benzodiazepines have anxiolytic properties as well as muscle relaxant effects that may be of value with chronic pelvic pain and vulvodynia. They also have a potential of dependence, making cautious use and pre-treatment counseling necessary. They are used in compounded vaginal or rectal suppositories, usually inserted at bedtime.66 67 Vaginal diazepam was compared to placebo in a randomized controlled trial in conjunction with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in women with vulvodynia. 68 Women in the diazepam cohort not only had a statistically significant decrease in visual analog scale (7.5-4.7, P=0.01), but also had an increased ability to relax the pelvic musculature, which likely plays a role in decreasing vestibular pain.

Botulinum toxin injection

Relaxing the hypertonic, overactive pelvic floor found in 80% of women with vulvodynia, a pelvic floor also replete with C fiber hyperplasia in the vestibular mucosa, supports chemodenervation of the pelvic floor muscles as a treatment option for women with LPV/PVD. Onabotulinumtoxin A (Botox) is a widely used drug for neuromuscular blockade. This drug is the most studied and successful in the treatment of lower urinary tract disease and appears to have some efficacy in treating vulvodynia as well.69

In an open label pilot study, seven women with LPV/PVD received 35 units of onabotulinumtoxin A. Thirty days later mean pain scores decreased from 8.1 to 2.9 on a 10 point visual analog scale. Total duration of effect was 14 weeks, with no reported adverse events. The promising results of this initial pilot have opened the way for randomized placebo controlled clinical trials. Subsequently, 64 women were randomized to placebo or 20 units of onabotulinumtoxin A injected into the bulbospongiosus muscle. At six months, curiously, both onabotulinum-a toxin and placebo groups had a decrease in pain scores. There were, however, no significant differences in pain between the two groups.70 There are many questions that need answers regarding Botox, but encouraging clues and rare side effects encourage ongoing work with a promising drug.

Interferon injections

Down-regulation of the expression of proinflammatory cytokines is the mechanism by which the signaling protein interferon works. It is effective against condyloma accuminata, as well as some leukemias and lymphomas.71 It is also a potent inhibitor of mast cells, which have been reported elevated in some cases of vulvodynia.72 Several small case studies, as well as a randomized trial in conjunction with surgery73 74 75 have reported moderate improvement in pain scales after submucosal injection of interferon into the vulvar vestibule. All these studies were done before 2000. Interferon should not be considered first-line therapy in the treatment of vulvodynia without further studies.76

Nerve blocks

A pelvic nerve block comprises targeted administration of long-acting anesthetic, corticosteroid, or other anti-inflammatory medications near pelvic nerves, performed by practitioners experienced in nerve block procedures. While pelvic nerve blocks are considered relatively safe and effective in decreasing some types of pelvic pain, the details need to be discussed in person prior to the block. Side effects are uncommon, but nerve injury, infection, hematoma, damage to surrounding structures, dissemination to and anesthetization of other local nerves, systemic toxicity, and allergic reactions are possible. Also important is a discussion to make sure the woman understands that a pelvic nerve block manages the pain for a period of time, but does not represent a cure. These blocks may target the pudendal nerve, the genitofemoral nerve, or the ganglion impar.

The vulva, perineum, and lower portion of the vagina are innervated by the pudendal nerve S2-4. From its sacral nerve root, the pudendal nerve passes posterior to the ischial spine which represents the lateral attachment point for the sacrospinous ligament. The nerve then branches out caudally. A clinician may palpate the ischial spine transvaginally,or may use an imaging modality.

The ilioinguinal nerve from L1-L2, and the genitofemoral nerve also from L1-L2 supply the anterior portion of the vulva, the mons, and inner thigh. The substantial variability in the anatomical course of the ilioinguinal nerve makes imaging by ultrasound prudent. The same imaging is also used for the genitofemoral nerve.

While the relationship between neuropathic pain and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is controversial, the relationship between chronic pain and the SNS is well established. Sympathetic nerve blocks have been used to treat chronic pain related to malignancy for many years. The ganglion impar (also known as Walther’s ganglion) is the only unpaired ganglion of the SNS at the sacrococcygeal junction level.77 It conveys sympathetic efferent input to and nociceptive afferent input from the perineum, distal rectum, perianal region, the distal urethra and vulva/scrotum, and the distal third of the vagina and supplies sympathetic innervation to the pelvic viscera. In a recent case series of four women successfully treated with ganglion impar blocks performed using fluoroscopic guidance, three had generalized vulvodynia. The authors propose that the block can be an effective interventional treatment for vulvodynia.78

Because the exact anatomical location of the nerves and impar call for use of imaging, a healthy choice involves locating a pain specialist or interventional radiologist at a large teaching hospital to perform/teach nerve blockade techniques.

Surgery

Surgical management for vulvodynia consists of vulvar excision and vestibulectomy and is often reserved for patients who have failed all previous medical attempts. Access information about vestibulectomy in Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia.

Conclusion

Vulvar pain affects up to 20% of women in their lives and the majority of women with vulvar pain have associated pelvic floor disorders. Because of the heterogeneity of vulvodynia and neuromuscular system involvement, successful treatment plans are multimodal and include physical therapy.79

References

- Marhan M, Saleh A. The microscopic anatomy of the hymen. Anat Rec 1994; 149:313-18.

- Basaran M, et al. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen; case reports and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64

- Liang C et al. Long-term follow-up of women who underwent surgical correction for imperforate hymen. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;269(1):5-8.

- Neill SM, Lewis FM. Basics of vulval embryology, anatomy, and physiology. In: Ridley’s The Vulva, 3rd edition, Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009:12

- Brookoff D. Genitourinary pain syndromes: Interstitial cystitis, chronic prostatitis, pelvic floor dysfunction, and related disorders. In: Smith H, ed. Current Therapy in Pain. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.p 205-15.

- Van Houten T. Anatomy of the pelvic floor and pelvic organ support system. In:Women’s Sexual Function and Dysfunction.Goldstein I, Meston C, Davis S. Traish A, Eds. Oxford, England. Taylor & Francis, 2006.

- Stoker J, Wallner C. The anatomy of the pelvic floor and sphincters. In: Stoker J, Taylor SA, DeLancey JOL, eds. Imaging pelvic floor disorders. 2nd revised ed. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2008. 1-29.

- Stoker J, Wallner C. The anatomy of the pelvic floor and sphincters. Stoker J, Taylor SA, DeLancey JOL, eds.In Imaging pelvic floor disorders, 2nd revised ed, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2008. 1-29

- Lee D, Lee L-J, Vleeming A, et al. The Pelvic Girdle: An Integration of Clinical Expertise and Research. 4th ed. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Churchill Livingstone: 2011

- Prather H, Dugan S, Fitzgerald C, et al. Review of anatomy, evaluations and treatment of musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain in women. PM R 2009;1(4):346-358.

- Hodges PW, McLean L, Hodder I. Insight into the function of the obturator internus muscle in humans: observations with development and validation of an electromyography recording technique. Kinesiol J Electromyor. 2014; 2(4):489-496.

- Bergeron S, Reed B, Wesselmann U, Bohm-Starke N.B. Vulvodynia. Nature Reviews/Disease Primers. 2020; 6:36

- Kearney R, Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, et al. Obstetric factors associated with levator ani muscle injury after vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107.144-149.

- Kearney R, Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, et al. Obstetric factors associated with levator ani muscle injury after vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107:144-149.

- Hutchinson D, Ali M, et al. Pelvic Floor Muscle training in the Management of Female Pelvic Floor Disorders. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports. 2022;17:115-124.

- ACOG Practice bulletin No. 155: Urinary Incontinence in Women. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126(5): e66-81.

- Weintraub A, Glinter H, and Marcus-Braun N. Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Braz J Urol. 2020 Jan-Feb;46(1):5-14.

- Bo K, Frawley HC, Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the conservative and nonpharmacological management of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 2017;28(2):191-213.

- Prager H, Dugan S, Fitzgerald C, et al. Review of anatomy, evaluation, and treatment of musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain. PM R. 2009;1(4):346-358.

- Pastore EA, Katzman WB. Recognizing myofascial pelvic pain in the female patient with chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012; 41(5):680-691.

- Meister MR, Shivakumar N. Sutcliffe S, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219(5):497. e1-497-e13.

- Prenderngast S, Akincilar E. Pelvic Floor Assessment of Vulvodynia. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I, eds. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons Publishers. 2021.

- Dietz HP. Pelvic floor trauma following vaginal delivery. Curr Opinion Obstet Gynecol, 2006; 18(5):528–537.

- Quinn M. Injuries to the levator ani in unexplained chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet Gynaecol, 2007; 27(8):828–31.

- Tetik S, Ozden YA. Vaginismus, Dyspareunia, and Abuse History: A systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2021 Sep; 18(9):1555-1570.

- Gorniak G, King PM. The peripheral neuroanatomy of the pelvic floor. J Women’s Heal Phys Ther. 2016; 40(1):3-14.

- Minassian VA, Lovatsis D, Pascali D, et al. Effect of childhood dysfunctional voiding on urinary incontinence in adult women. Obstet Gynecol, 2006;107(6): 1247–1251.

- Peters KM, Carrico DJ. Frequency, urgency, and pelvic pain: treating the pelvic floor versus the epithelium. Curr Urol Rep, 2006; 7(6):450–455.

- Gardella B, Iacobone A, Musacchi V, et al. Effect of local estrogen therapy (LET) on syndrome (IC/BPS). Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015 Aug 10:1-5.

- Simons DG, Travell JG, et al. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, volume I. The Upper Extremities. Baltimore, MD. Williams & Wilkins. 1983.

- Weiss JM. Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and urgency-frequency syndrome. J Urology 2001 Dec ( 166 (6):2226-31.

- Prendergast SA, Rummer EH. Pelvic Pain Explained. Rowman & Littlefield, Latham, MD 2016, p. 18.

- Butrick CW. Interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain: new insights in neuropathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2003;46(4):811–823.

- DeSantana JM, Sluka KA. Central mechanisms in the maintenance of chronic widespread noninflammatory muscle pain. Current Pain Headache Rep, 2008; 12(5):338-343.

- Rana N, Drake MJ, Rinko R. et al. The fundamentals of chronic pain assessment, based on International Continence Society recommendations. Neurourol Urodyn 2018. 37:S32-S38.

- Pastore EA, Karzman WB. Recognizing myofascial pain in the female patient with chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2012;41:680-69.

- Harm-Hernandes I, Boyle V, Hartmann, D, et al. Assessment of the Pelvic Floor and Associated Musculoskeletal System: Guide for Medical Practitioners. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. 2021; 27(12):711-718.

- Meister MR, Shivakumar N, Sutcliffe S, et al. Physical examination techniques for the assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet; 2019(5):497. E13.

- Harm- Hernandes I, Boyle V, Hartmann, D, et al. Assessment of the Pelvic Floor and Associated Musculoskeletal System: Guide for Medical Practitioners. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. 2021; 27(12):711-718.

- Herschorn S. Female pelvic floor anatomy: the pelvic floor, supporting structures, and pelvic organs Rev Uro 2004. 6 (Supp l5):S2-S10.

- Meister MR, Shivakumar N, Sutcliffe S, et al. Physical examination techniques for the assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 219(5):497. E13.

- Herschorn S. Female pelvic floor anatomy: the pelvic floor, supporting structures, and pelvic organs. Rev Urol 2004;6 (Supp l5): S2-S10.

- Prather H, Camacho-Soto A. Musculoskeletal etiologies of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2014;41(3):433-442.

- Boonstra AM, Stewart RE, Kole AJ. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the numeric rating scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: variability and influence of sex and catastrophizing. Front Psychol 2016; 7:1466.

- Jones KR, VOjir CP, Hutt E, et al. What determines whether a pain is rated as mild , moderate, or severe? The importance of pain beliefs and pain interference. Clin J Pain 2017 (5):414-421.

- Bittelbrunn CC, de Fraga R, Martins C. Pelvic floor physical therapy and mindfulness: approaches for chronic pelvic pain in women- a systemic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2022 Apr 6. Doi:1007/s00404-022-06514-3

- Hutchinson D, Marwan M, Zilloux J, et al. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training in the Management of Female Pelvic Floor Disorders. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports 2022 17:115-124.

- Stein A, Hartmann D, Parrotte K. Physical Therapy Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 2nd ed. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons. 2021; 185-192.

- Prendergast SA, Rummer EH. Pelvic Pain Explained. Rowman & Littlefield, Latham, MD 2016: 40.

- Stein A, Hartmann D, Parrotte K. Physical Therapy Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 2nded. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons. 2021; 185-192.

- Lew J, Kim J, Nair P. Comparison of dry needling and trigger point manual therapy in patients with neck and upper back myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2021 Jun;29(3):136-146.doi: 10.1080/10669817.2020.1822618. Epub 2020 Sep 22.

- Stein A, Hartmann D, Parrotte K. Physical Therapy Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 2nd ed. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons. 2021; 185-192

- Stein A, Hartmann D, Parrotte K. Physical Therapy Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 2nd ed. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons. 2021; 185-192

- Weiss JM. Chronic pelvic pain and myofascial trigger points. Pain Clinic. 2000; 2(6):13-18.

- Arnouk A, De E, Rehfuss A, Cappadocia C, Dickson S, Lian F. Physical, complementary, and alternative medicine in the treatment of pelvic floor disorders. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2017; 18: 47.

- Wagner B, Steiner M, et al. The effect of biofeedback interventions on pain, overall symptoms, quality of life and physiological parameters in patients with pelvic pain. Weiner klinische Wochenschrift. 2022; 134, pages 11–48.

- Stein A, Hartmann D, Parrotte K. Physical Therapy Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 2nd ed. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I. Hoboken, NJ. John Wiley & Sons. 2021; 185-192.

- Bergeron S, Brown C, Lord MJ. Physical therapy for vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a retrospective study. J Sex Marital Ther 2002; 28:183-192.

- Morin M, Binik Y, Bourbonnais D, et al. Heightened pelvic floor muscle tone and altered contractility in women with provoked vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2017; 14:592-600.

- Morin M, et al. Efficacy of multimodal physiotherapy treatment compared to overnight topical lidocaine in women with provoked vestibulodynia:a bi-center randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2016;13: S243.

- Xibei J, Rana T, Whitmore KE. Gynecological associated disorders and management. Int J Urol 2019; Jun 26 Suppl1:46-51.

- Xibei J, Rana T, Whitmore KE. Gynecological associated disorders and management. Int J Urol 2019; Jun 26 Suppl 1:46-51.

- Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Sep;116(3):583-593. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e9e0ab.

- Leo RJ. A systematic review of the utility of anticonvulsant pharmacotherapy in the treatment of vulvodynia pain. J Sex Med 2013;10:2000-2008.

- Bachmann GA, Brown CS, et al. Effect of gabapentin on sexual function in vulvodynia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan; 220(1): 89.e1–89.e8.

- , , et al. Intra-vaginal diazepam for high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2013; 24: 1915-23.

- , , , , . Retrospective chart review of vaginal diazepam suppository use in high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010; 21: 895–9

- Murina F, Felice R, et al.Vaginal diazepam plus transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation to treat vestibulodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018; 228:148-153.

- Avonstondt AM, Ingber MS. Treatment of Vulvodynia with Pelvic Floor Muscle Relaxants/Injections. In: Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 2nd ed. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I., eds. Hoboken , NJ. John Wiley & Sons, 2021;193-197.

- Petersen CD, et al. Botulinum toxin type A: a novel treatment for provoked vestibulodynia? Results from a randomized placebo controlled double blinded study. J Sex Med. 2009; 6(9):2523-2537.

- GroysmanV. Vulvodynia: new concepts and review of the literature. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28(4):681-696.

- Hilton S, Vandyken C. The puzzle of pelvic pain: a rehabilitation framework for balancing tissue dysfunction and central sensitization. In: Pain physiology and evaluation for the physical therapist. J Women’s Health Phys Ther. 2011;35(3):103-113.

- Kent HL, Wisniewski PM. Interferon for vulvar vestibulitis. J Reprod Med. 1990; 35 120:1138-1140.

- Bornstein J, Pascal B, Abranovici H. Intermuscular beta-interferon treatment for severe vulvar vestibulitis. J Reprod Med. 1991;38 (2): 117-120.

- Bornstein J, Zafari D, Goldschmid N, et al. Vestibulodynia: a subset of vulvar vestibulitis or a novel syndrome? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 177 (6):1439-1433.

- Stein A, Hartmann D, Parrotte K. Treatment of vulvodynia with Pelvic Floor Muscle Relaxants/Injections. In:Female Sexual Pain Disorders. Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Goldstein I., eds. Hoboken, NJ., Wiley & Sons. 2021:185-192.

- Oh G, Kenis-Coskun O. Ganglion blocks as a treatment of pain: current perspectives. J Pain Res 2017;10:2815–26.

- Hong DG, Hwang SM, Park JM. Efficacy of ganglion impar block on vulvodynia. Medicine: July 30, 2021; 100 (30): e26799. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026799.

- Rummer EH, Prendergast SA. Pelvic Pain Explained: what Everyone Needs to Know. Lanham, MD. 2016.Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.