Introduction

Please note: we are updating this section. 5-20-24

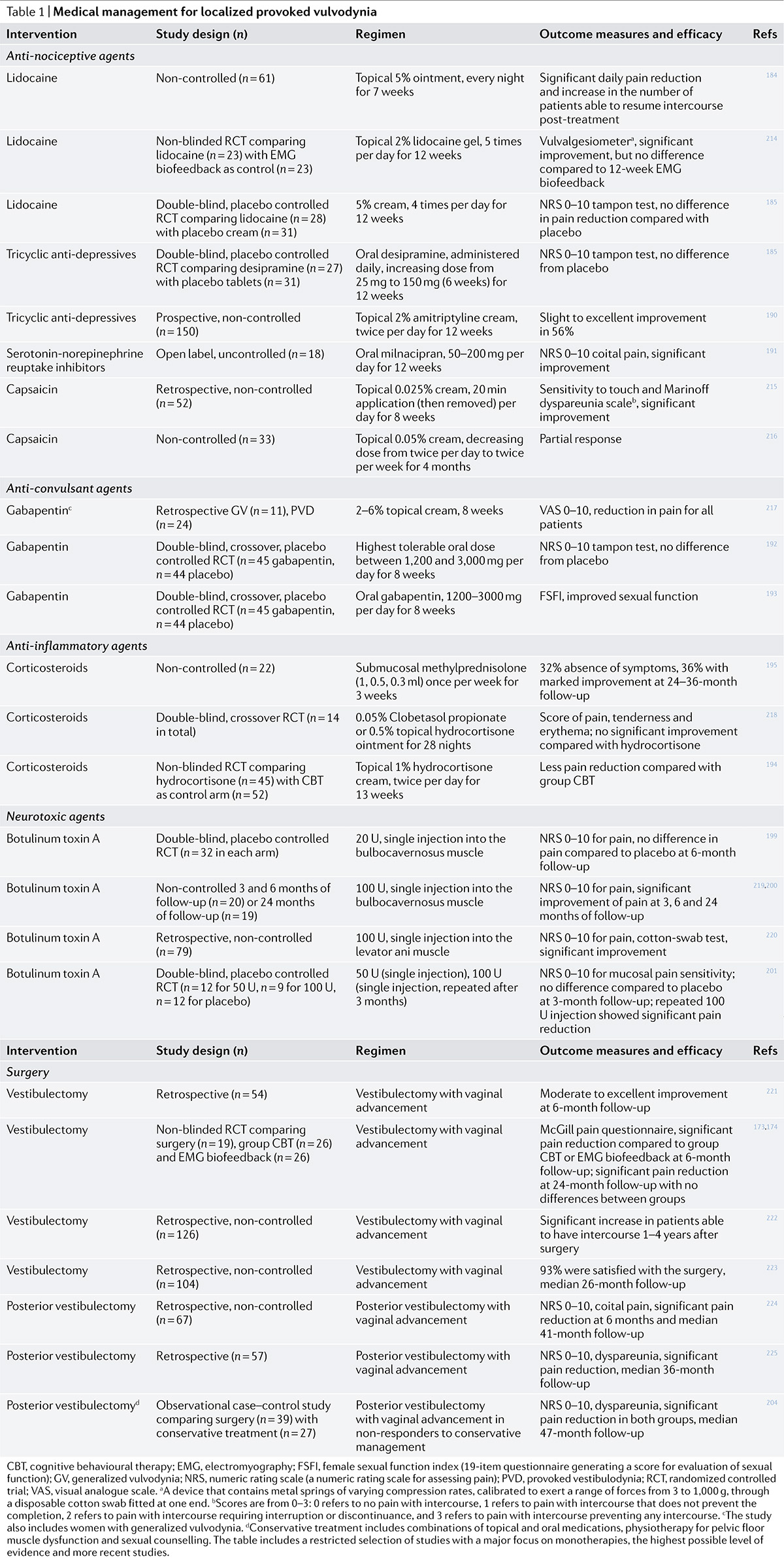

Vulvar pain from a specific disorder often resolves with treatment or control of the condition, but in some cases, treatment of the pain is necessary in addition to treatment of the disorder. Currently there is no standardized treatment for vulvodynia, by definition pain of unknown cause. Well-conducted studies of vulvovaginal pain of any type are few, and the level of evidence is low. Randomized controlled studies are rare, whereas case-control studies and clinical observations are common.1 Faced with debilitating problems, clinicians work with available information and reliance on clinical experience, sometimes despite current study information. As one expert expresses, “They (the tricyclic antidepressants) are extremely useful in managing the neuropathic component of vulvar pain. Despite a recent, apparently well-conducted study showing lack of benefit, my 25 years of personal clinical experience with tricyclics convince me that I should wait for follow-up studies before abandoning this therapy.”2

Patients with any chronic pain are often frustrated and anxious. Vulvar pain and vulvodynia, with their impact on a woman’s femininity and sexual function (Vulvar pain and sexuality), are no exception. Women with vulvar pain and vulvodynia have failed many treatments and have seen many physicians.3 They need to be reassured that their symptoms are real, and that treatment is available for this complex set of disorders.4 Treatment must be individualized as there is no “one size fits all” therapy. Women, and their partners, also need to understand that there is no single modality to “fix” the problem; it is the combination of a variety of approaches that brings amelioration. A multidisciplinary team approach is needed to address the different components of each case. Most patients need a combination of psychosexual, pharmacologic, and rehabilitative/physiotherapy-based interventions with guidance from a team that may include gynecology, physiotherapy, clinical psychology, sexual counseling, and pain specialists.5 Treatment choices must include involvement of the partner when appropriate, consideration of the local health care system, and attention to cost.6

A precise timeline is not possible, and progress is slow. A woman needs a week or two (often having increased slowly over a week or two) at the therapeutic level of any medication. She may say that there is no difference, but close questioning may reveal, for example, that her pain level has gone from 7/10 to 6/10 most days. She may have had a day or two free of pain. Or, she may notice that a pain flare lasts a shorter duration. Quantified information is essential in order to see the picture and continue a potentially helpful medication. At each visit, obtain a quantified number (0-10), for highest pain level and number of days that this level exists each month. (Annotation I: Pain mapping and the Q-tip test).

Desensitization

Identify and eliminate any possible pain triggers.

- Stop offending irritant activities on the vulva (Annotation J: Lifestyle issues). Although soap is an unlikely culprit, every aspect of the patient’s lifestyle must be explored for possible contributing factors.

- Diagnose and suppress any vaginitis: candida, inflammatory vaginitis, trichomonas (Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy, and cultures). Remember that bacterial vaginosis is not a significant cause of pain.

- Suppress herpes if active (Centers for disease Control: www.cdc.gov/std/Herpes/treatment.htm)

- Marsupialize recurrent/persistent Bartholin cysts (Atlas of vulvar disorders). In our experience, we have seen provoked pain in the vestibule chronically inflamed by such cysts.

- Provide adequate local estrogen if there is atrophy (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium)

- Diagnose and treat lesions of dermatitis, dermatosis (Atlas of vulvar disorders)

- Recognize systemic disease such as drug reaction, Sjögren, or Crohn disease, and treat vulvar manifestations (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium)

- Consider seminal plasma allergy if history suggests (Annotation J: Lifestyle Issues)

- Consider issues such as painful bladder syndrome, interstitial cystitis, pelvic floor dysfunction (Annotation L: The pelvic floor)

- Refer to physiatrist or physical therapist to evaluate and treat musculoskeletal problems possibly affecting pelvic floor and pudendal nerve. (Annotation L: The pelvic floor).

- Consult experts regarding pain in other areas, (e.g., gynecologist for endometriosis, urologist for interstitial cystitis), to make sure that all components of a regional pain syndrome are addressed.

- Always ask yourself if there is any possibility of a pre-malignant or malignant lesion (Atlas of vulvar disorders).

Educate about vulvar pain.

Use handouts (Patient handouts) and website referrals, and local support groups. Emphasize that pain may need to be managed, not cured. Describe the typical slow and gradual regression of pain that may occur. Discuss global impact on every aspect of sexuality (Vulvar pain and sexuality), emphasizing that pain must be managed first; then work on sexual function can occur. Discuss the psychology of pain, factors that worsen pain, and the importance of taking charge. Suggest Margaret Caudill’s How to Manage Pain Before It Manages You, 3rd edition. New York, Guilford Press, 2009. Offer counseling for support, anxiety, depression, or relationship problems.

Provide information about comfort measures.

Flares of pain can be minimized by a variety of factors (Self Help Tips for Vulvar Skin Care: http://www.nva.org). By far, the most important comfort measure is the technique of “Soak and Seal:” sitting in comfortable water (tub, sitz bath under the toilet seat, or gentle hand held shower for 5-10 minutes twice daily). A woman who is physically unable to use the tub or sitz bath may protect the bed with plastic sheeting and use sopping wet compresses. Pat dry gently; then seal in the moisture with a film of petrolatum or mineral oil.

Provide guidelines for sex

We ask women who have pain on penetration to stop vaginal intercourse until there has been some improvement in symptoms. Ongoing intercourse in the presence of pain is a negative reinforcer and can lead to secondary vaginismus. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance for genital exam). We encourage open communication between a woman and her partner about her pain with the effort to prevent feelings of rejection. We encourage intimacy and the pursuit of any mutually agreed upon pain-free alternatives to vaginal intercourse.

If sexual intercourse is possible with a level of comfort acceptable to the woman, we recommend use of a lubricant such as a few drops of plain baby oil without fragrance; this may be well tolerated as long as condoms are not being used. Latex condoms are not compatible with oil-based lubricants or medications. In women using condoms, a water-based lubricant is appropriate (e.g., an iso-osmotic, pH balanced product, e.g., Pre-Seed®). Some women find a decrease in sexual pain with use of certain sexual positions.

Pharmacologic treatment for vulvodynia

Topical medications

Lidocaine 5% ointment

5% Lidocaine applied to the vestibule 3 times daily and on a cotton ball in the vestibule overnight was reported helpful for localized provoked vulvodynia as a treatment in one study.7 It was no better than placebo in another.8 Lidocaine has not been studied for generalized vulvodynia.

We have found that lidocaine can be a helpful management modality for both types of vulvodynia. Women with generalized vulvodynia or vulvar pain from a known cause often benefit from lidocaine during pain or itching flares. In some cases where sexual intercourse is painful, we ask a woman to apply one teaspoon to the vestibule 10-15 minutes prior to intercourse. After 15 minutes, any excess is wiped away so that it does not come in contact with her partner. Lubrication can then be added. (Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy, and cultures). Prior to Pap smear, colposcopy, or other procedures, the same Lidocaine application is helpful. We always ask a woman to use Lidocaine with dilators or with physical therapy treatments. (Annotation D: Patient tolerance of the genital exam). Women should be warned that Lidocaine may burn on initial application, the sensation lasting about 45 seconds, before numbing takes effect. This burning, as long as it stops after the first 60 seconds, is not harmful.

Lidocaine is sometimes prescribed in 2% gel form. Since this contains alcohols, it often burns more than the ointment form.

Lidocaine 2.5%-prilocaine 2.5% ointment combines two amide topical anesthetics; it provides more anesthetic relief especially in the vestibule, but may cause more burning as it takes effect.

A randomized trial that evaluated treatments for vestibulodynia compared topical Lidocaine 5% applied to the vestibule four times per day for 16 weeks to electromyographic biofeedback.9 Both treatments resulted in significant improvement in pain, sexual function, and psychosocial adjustment at 12-months follow-up. There were no differences in outcome between the two treatments, but there was the limitation that the trial was underpowered.

Lidocaine ointment 5% has 50 milligrams of lidocaine in 1 gram.

Use of local lidocaine should not exceed 5 g of Lidocaine Ointment USP per day, 5% containing 250 mg of lidocaine base (equivalent chemically to approximately 300 mg of Lidocaine hydrochloride). This is roughly equivalent to squeezing a six (6) inch length of ointment from the tube. In a 70 kg adult, this dose equals 3.6 mg/kg (1.6 mg/lb) lidocaine base.

Topical tricyclic antidepressants or anticonvulsants

A variety of topical medications, many compounded from medications used by mouth (e.g., amitriptyline, gabapentin), are being tried for the relief of pain, It is thought that these tend to have fewer side effects compared with oral forms. These may be applied directly to a painful area, but unless you ask a pharmacist to compound with the pH of the medications adjusted towards neutrality (and sometimes even if pH is adjusted), the medication can burn in the vestibule. In this case, the topical cream or ointment may be applied to the mons pubis or thigh, although this is an unstudied method.

Topical amitriptyline 2%/baclofen 2% cream (ABC) 0.5cc three times daily brought a decrease in the extent to which the condition interfered with social activities, easier lubrication, and lower level of pain with intercourse. No patient had systemic side effects Topical ketamine 2%, ketoprofen 6%, amitriptyline 0.6%, lidocaine 2.5%, prilocaine 2.5%, clonidine 2%, pH balanced, 1/4 tsp applied three times daily has been suggested by a number of pain clinicians, but no studies exist.

Topical gabapentin 2%, 4%, and 6% 0.5 cc applied three times daily was reported helpful after eight weeks10 in 32 women with localized vulvodynia. Common adverse effects related to the oral gabapentin were not reported. By statistical rating, however, this report is considered insufficient evidence of efficacy.11

In a recent systematic review, fair evidence for lack of efficacy was found for topical cromolyn12 and nifedipine.13 There was insufficient evidence regarding capsaicin.14 15 In over twenty years of practice, we have seen one patient who tolerated the burning of capsaicin and reported significant improvement with it. Evidence for the efficacy of montelukast,16 steroids,17 and ketoconazole18 is also insufficient.

Injections and blocks

Botulinum toxin injections are being used for both provoked and unprovoked pain, injected into the vestibule and/or pelvic floor muscles to reduce hypertonicity. In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, injection of botulinum toxin type A 80 units into the pelvic floor muscles has been shown more effective than placebo at reducing pain and pelvic floor pressure in women with chronic pain and muscle spasm.19 But in another randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled study injection of 20 I.E. Botox in the bulbospongiosis muscles of women diagnosed with vestibulodynia did not reduce pain, improve sexual functioning, or impact the quality of life compared to placebo, evaluated at 3 and 6 months follow up. In a systematic review, there was fair evidence of a lack of efficacy for botulium toxin injections for localized provoked vulvodynia.20 For generalized vulvodynia there was insufficient evidence in a case report,21 and a study of a small number of women.22 It appears that the optimum dose and injection technique of botulinum toxin remains to be determined and that a multi-modal approach that includes both physical therapy to the pelvic floor and psychosexual support needs evaluation.

Success with injections of steroid/lidocaine has been limited to an uncontrolled group of 21 women with localized, provoked vulvodynia23 and a single case report, also of localized provoked vulvodynia.24 Our experience suggests that, at best, these bring only temporary relief.

Interferon injections, both intralesional and intramuscular, appeared hopeful for localized provoked vulvodynia in the past25 26 but are not in widespread use at present. Our experience was that they were either completely ineffective or that any gained benefit was short-lived (placebo).

An observational study including 27 women reported serial nerve blocks (combination of caudal, epidural, pudendal, and local infiltration) significantly improved vestibular pain. Follow-up, however, was limited to 8 to 12 weeks.27 Pudendal and spinal nerve blocks have been used for diagnosis and management of generalized vulvodynia. Guided image blocks are preferred to support or rule out the diagnosis since failure of traditionally performed pudendal nerve block in labor may be due to operator error and not necessarily the absence of PN. To date, evidence is limited to small studies.

Since the autonomic sympathetic nervous system conveys nociceptive messages from viscera to the brain, interventions with the sympathetic system are being used for perineal pain management. Ganglion impar blocks, steroid injection around the terminal branch of the sympathetic chain in the presacral space, have been performed with good results for generalized vulvodynia.28 Hypogastric plexus and L2 lumbar sympathetic blocks are being investigated.

Oral medications

In general, improvement with any centrally acting drug takes weeks and is uneven. Pain may seem to lessen but then return; expect a trend of slow diminution of pain and less frequent and less intense flares.

The medications used for pain management have a number of side effects and interactions. Patient education is essential, especially in view of the fact that an unexpected side effect e.g., burning with Lidocaine or sedation with tricyclic may cause rejection of medications that could otherwise be helpful.

Other centrally acting drugs not included here are familiar to clinicians in pain units.

Although antidepressants and anticonvulsants are considered by many to be effective for vulvodynia, there is only one randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study that showed a placebo response of 33% for desipramine in localized provoked vulvodynia.29

Tricyclics

The mechanism of action of tricyclics has been thought to be related to inhibition of the re-uptake of transmitters– specifically nor-epinephrine and serotonin. It is possible that the mechanism may be more closely related to anticholinergic effects. Tricyclics affect sodium channels and the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor.30

Tricyclic antidepressants (amitryptiline, nortryptiline, desipramine) are effective compounds in the treatment of neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, low back pain, and headaches according to meta-analyses and clinical studies of these agents retrieved through the use of MEDLINE, Google scholar, and Cochrane databases.31 They are a common treatment for vulvodynia. Nevertheless, as above, a well-designed recent study showed desipramine to be no better than placebo or topical lidocaine for provoked vulvodynia.32 Another randomized study demonstrated that low-dose amitriptyline (10-20 mg) and desipramine 150 mg are ineffective for provoked vulvodynia.33 Studies with higher doses of amitriptyline (40-60 mg/day) suggested that 50% or greater improvement in pain scores can be achieved for both provoked and unprovoked vulvodynia.34 Because it has been thought that doses lower than those used to treat depression could be used for pain, inadequate dosage may be a major flaw in treatment and treatment studies of tricyclics.

We emphasize to patients that tricyclics are being used for pain, not depression, although the anti-depressant effects may be useful.

We begin treatment with the less sedating nortriptyline or desipramine: 10 mg at bedtime and increase the dose by 10 mg every five days to 50 mg at bedtime. If the patient is extremely sensitive to medications, nortriptyline syrup (10 mg/tsp) can be used to help the patient acclimate to the drug side effects with small increments of dose. Patients over 65 years of age also need slower (weekly) increases. If the patient is tolerating the side effects, the dose should be slowly increased to a total maximum dose of 100 to 150 mg per day. Common reasons for treatment failure are inadequate dosage or a short duration of therapy since it takes weeks to observe an effect. We explain that the pain did not evolve overnight and is not going to disappear quickly. A tricyclic with dosage of 100 to 150 mg for three months without improvement would prompt us to move to another agent.

Both nortriptyline and desipramine are less sedating than amitriptyline and have fewer anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, sweating, palpitations). Sedation is often transient and improves with time on the medication. Constipation is a common problem and needs proactive management to prevent rejection of the drug by the patient for this reason. A patient with irritable bowel syndrome manifested as constipation may tolerate tricyclics poorly without aggressive management: use of fiber supplements, docusate, or senna. Mild vertigo and palpitations are common. An electrocardiogram should be obtained in women over 50 years of age and should be normal prior to initiating therapy. If it is abnormal, or if the woman has a history of a cardiac arrhythmia, we suggest consultation with the patient’s primary care provider or a cardiologist. Sun sensitization can occur.

Checking with the glaucoma patient’s ophthalmologist prior to prescribing a tricyclic is also recommended.

*Serotonin syndrome: Drug interactions with serontonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI) can lead to the serotonin syndrome. The syndrome can be mild to life threatening. It is classically associated with the simultaneous administration of two serotonergic agents, but it can occur after initiation of a single serotonergic drug or increasing the dose of a serotonergic drug in individuals who are particularly sensitive to serotonin. The syndrome is thought to be uncommon but possibly increasing with the increased use of SSRI medications.

Mental status changes can include anxiety, agitation, restlessness, and disorientation. Diaphoresis, tachycardia, hyperthermia, hypertension, vomiting, and diarrhea represent autonomic involvement. Neuromuscular hyperactivity can manifest as tremor, muscle rigidity, myoclonus, hyperreflexia, and bilateral Babinski sign.

The diagnosis is clinical; serum serotonin concentrations do not correlate with clinical findings, and no laboratory test confirms the diagnosis.35 Treatment includes discontinuation of all serotonergic medications, supportive care, sedation with benzodiazepines, and use of serotonin antagonists.36

Serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

The SSRI medications have some efficacy in the management of pain but are less studied and less widely used than other CNS active medications.

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine (Prozac) given in a fixed dose of 20 mg/ day in one study was not superior to placebo37, but in another study that allowed dose increases from 20 to a maximum of 80 mg/day, the medication was significantly more effective than placebo38 ; the effect on pain was independent of change in mood.

Paroxetine

In a trial that randomized 116 patients and followed their composite scores on a fibromyalgia impact questionnaire for 12 weeks, an escalating dose of paroxetine (Paxil)in a continuous release formulation (12.5 mg/day to 62.5 mg/day) was compared with placebo. Patients assigned to paroxetine achieved a ≥25 percent improvement in fibromyalgia impact scores (57 versus 33 percent). Among those who completed the assigned treatment, the response rates were higher in those receiving paroxetine than placebo (66 versus 33 percent, respectively).39

Fluvoxamine

Fluvoxamine (Luvox) was compared with amitriptyline in a study that randomized 68 patients to one of the two active treatments for four weeks.40 Pain relief was not significantly different in the two groups.

Citalopram

Citalopram (Celexa)is not consistently noted to be helpful for pain in two small studies of patients with fibromyalgia.41 42

Serotonin norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine is a potent inhibitor of neuronal serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake and a weak inhibitors of dopamine reuptake. A small study reported efficacy of venlafaxine (Effexor) 225-375 mg/d orally for neuropathic pain.43 Another reported efficacy of 75-225 mg/day.44 It has not been studied for vulvodynia. It is started at 37.5 mg orally two times per day and increased by 37.5 mg every four days to a maximum of 375 mg/day; a sustained release form may be substituted for easier dosing. Prior to starting, a check for drug interactions is important. The medication should not be abruptly discontinued, but tapered.

Common side effects include headache, somnolence, dizziness, insomnia, nervousness and anxiety. Hypertension is dose related. Nausea and dry mouth are also common. Difficulty with orgasm, muscle weakness, and diaphoresis are listed. Antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal thinking in children, adolescents, and young adults (18-24 years). Patient and her family need to be cautioned to be observant and to communicate concern to clinician.

Duloxetine

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is an inhibitor of neuronal serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake and a weak inhibitor of dopamine reuptake. It has been used off-label for treatment of vulvar and pelvic floor pain. There is fair evidence for the use of duloxetine in neuropathic pain,45 but it has not been studied in vulvodynia. We start treatment at 20 mg orally each day for seven days and then increase by 20 mg each week to 60 mg daily. Doses up to 120 mg/day administered in clinical trials have offered no additional benefit and can be less well tolerated than doses of 60 mg/day. Prior to starting, a check for drug interactions is important. The medication should not be abruptly discontinued, but tapered.

A common side effect is nausea, often managed by taking the medication with food or using an anti-nausea medication. Headache, fatigue, constipation or diarrhea are also common. Somnolence (caution regarding driving or operating machinery) and insomnia are both dose related. Antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal thinking in children, adolescents, and young adults (18-24 years). Patient and her family need to be cautioned to be observant and to communicate concern to clinician.

Anticonvulsants

Gabapentin (Neurontin), though FDA approved for the treatment of the neuropathic pain of post-herpetic neuralgia, has not been studied in localized provoked vulvodynia, but is used for treatment and considered helpful. It is a gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogue, which was synthesized to mimic this neurotransmitter. Gabapentin binds to the α2δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels in the central nervous system. It has been proven that gabapentin halts the formation of new synapses, therefore decreasing neuropathic pain.46

Successful use of gabapentin for generalized vulvodynia is reported.47 In another study of 152 women with generalized unprovoked vulvodynia treated with gabapentin, (64 percent) achieved resolution of at least 80 percent of their symptoms.48 These studies are not, however, considered sufficient evidence of efficacy.49

We start gabapentin at 100 mg at bedtime, explaining that next-day sedation and mental slowness are transient and clear on an individual basis over two to five days or longer. We suggest increasing at the patient’s own rate, to a total of 1000 mg at bedtime. If this is tolerated and appears helpful (gabapentin works quickly enough that patients start to perceive improvement at 400- 500 mg), the patient may divide the doses over the day and continue increasing by 100 mg every two to five days. Gabapentin is thought to be a failure if there is no improvement on 3000- 3600 mg per day, but some patients are unable to tolerate doses that high. Some experts start the anticonvulsant at 300 mg at bedtime and increase by 300 mg every two days. If gabapentin is helpful but the patient cannot increase because of side effects, another medication may be added such as a tricyclic. (above, Tricyclics).

Gabapentin does not have the anti-cholinergic side effects of the tricyclic antidepressants; however, it may produce sedation. The dose may be moved back to 6-7 in the evening if morning sedation persists.

The medication may also cause dizziness, and ataxia, headache, or gastro-intestinal upset. Headaches may be exacerbated. Hypertension may occur.

Visual blurring is reported as well as edema of hands and feet. Side effects may be minimized by a low dose initially and gradual increase of the dose. Gabapentin has the advantage of no adverse interactions with other medications so that it may be combined with other pain management drug if augmentation of efficacy is needed.

Pregabalin

Pregabalin is, like gabapentin, approved for the treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia, and is now also being used off-label for the treatment of other pain. It has not been evaluated for provoked vulvodynia. Like gabapentin, it is also a gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogue, synthesized to mimic this neurotransmitter. Pregabalin is a drug that is related in structure to gabapentin. Compared with gabapentin, pregabalin is more potent, absorbs faster and has greater bioavailability.50 Higher potency leads to fewer dose related adverse effects. Patients often call it “smart gabapentin.”

There is fair evidence with pregabalin of efficacy for pain reduction in a number of neuropathic pain problems, but none specific for vulvodynia and the pelvic floor. It is however used off-label for the treatment of generalized unprovoked vulvodynia.

Pregabalin can be given less frequently (twice daily) than gabapentin (usually three times daily). Side effects of sedation, dizziness, and ataxia can be more troublesome and it is a schedule V controlled substance. We start pregabalin at 50 mg orally at bedtime for three days, and then increase to 50 mg twice per day for three days, and then 50 mg three times per day. It may be increased in the same fashion to a maximum of 600 mg daily, if tolerated.

Its side effects are similar to those of gabapentin. Common side effects include dizziness, somnolence, ataxia, peripheral edema of hands and feet, weight gain, and blurred vision. If side effects are a problem, a slower increase may help the patient tolerate higher doses.

The protocol for gabapentin is discussed above. Pregabalin (Lyrica) can be combined with a tricyclic.51

Other medications studied for vulvodynia treatment

Fluconazole

In the only randomized clinical trial with placebo group, Bornstein, et al examined the efficacy of fluconazole for provoked vulvodynia. After a six month regimen of 150 mg per week there was no significant difference between the treatment group (15% success rate) and the placebo group (30% success rate).52

Other oral medications not studied for vulvodynia

Estrogen

Local estrogen therapy can be helpful through its beneficial effect on the epithelium if atrophic changes are present. It is not a pain management drug per se and has not been studied for pain. In our experience, the low dose vaginal estrogen ring and estradiol tablets are helpful, but sometimes do not provide an adequate estrogen effect to the vestibule itself. We suggest treatment with a quarter teaspoon of estradiol cream 0.1 percent to the vestibule daily for four weeks in order to achieve the desired effect; the frequency can then be decreased to one to two times weekly. Both estradiol and conjugated equine estrogen cream may cause burning because of alcohols and preservatives in the base. Estradiol cream can also be compounded if necessary to eliminate this problem, but for some women estradiol still burns. This can be managed with reduction of the compounded estradiol strength to 0.05% or with the application of a layer of petrolatum under the estradiol, effectively diluting it.

Diazepam

Intravaginal diazepam suppositories as an adjunctive treatment for high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction and sexual pain have given significant clinical improvement in one report.53 We prescribe 5-10 mg in a compounded vaginal suppository nightly for 30 days, with titration of dosing frequency at successive visits as pelvic floor physical therapy progresses. It is possible to insert a diazepam 10 mg tablet vaginally although some women have difficulty retaining the tablet. We have had several women report a blue green discoloration of vaginal secretions after local diazepam. In our experience, vaginal Valium is less sedating than oral valium; if sedation occurs, we lower the dose to 2.5 mg. The potential for habituation with vaginal diazepam is unknown; patients need to understand that habituation may occur.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs have not been adequately studied for vulvodynia; they are widely anecdotally reported to be ineffective. In one study of provoked vulvodynia, the observed low expression of cyclooxygenase 2(COX 2) and inducible nitric oxide synthetase (iNOS)54suggests that NSAIDs would not be helpful.

Opioids

Opioids have shown consistent efficacy in neuropathic pain,55 and patients with nociceptive pain syndromes may also require opioid therapy if they do not respond to nonopioid analgesics, or if their pain is severe at the outset.56 Use of opioids has not been well studied for vulvodynia. We have found that it is helpful to use over the short-term an opioid, such as acetaminophen with codeine, 625/30 every 4-6 hours while awaiting the efficacy of a longer acting medication, such as one of the tricyclic antidepressants. Proactive management of constipation is essential.

Tramadol

Tramadol (Ultram™) inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine and may provide analgesia through this mechanism. Systematic reviews found that tramadol was effective for relief of neuropathic pain57 and pain in patients with fibromyalgia.58

The dose is 50-100 mg by mouth every 4-6 hours not to exceed 400 mg/day.

Tramadol has similar side effects of other weak opioids, although the incidence of gastric upset may be higher. Seizures are an additional risk, particularly in patients who take antidepressants, neuroleptics, or other drugs that decrease the seizure threshold. Tramadol has been associated with increased risk for suicide,59 and must be used with caution in patients who have emotional disturbance, suicidal ideation or attempts in the past, or are addiction-prone. Although tramadol is not scheduled as a controlled substance, dependence has been reported.60

Non-pharmacologic treatment for vulvodynia

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

The premise of cognitive behavioral therapy is that changing maladaptive thinking leads to change in affect and in behavior.61 For provoked vulvodynia, the treatment aims to decrease pain, reduce fear of pain, and reestablish satisfying sexual function.62 The only randomized study that looked at CBT randomized participants to group CBT (CBGT), biofeedback, or vestibulectomy. Women in the three treatment groups reported significant improvement in their pain (47% – 70% for vestibulectomy, 19%-35% for biofeedback, and 21% – 38% for CBGT). The surgery was therefore significantly more successful than the other two treatments for pain reduction, but all three treatments yielded equally significant psychosexual functioning improvements. There was a significantly lower attrition rate for the CBGT group compared with surgery. CBGT participants were more satisfied with their treatment than those in the biofeedback group.63

The only other study of CBT for provoked vulvodynia was a prospective evaluation of CBGT efficacy in a large sample. The researchers reported a significant decrease in dyspareunia as well as a significant improvement in sexual satisfaction and perceived pain control.64

CBT has not been studied for generalized vulvodynia. CBT appears to be a promising, readily available modality without negative side effects in need of further study.

Physical therapy to the pelvic floor

Pelvic floor physical therapy and biofeedback are modalities that are used frequently by those who treat women with vulvodynia. These are discussed in Annotation L The pelvic floor.

Adjunctive and alternative therapy

There are few studies that have looked at adjunctive or alternative therapies. The ones that have been done so far lack controls and randomization.

Hypnotherapy

A single case study65 and another study of eight women66 showed significant reduction of pain.

Hypoallergenic vulvar hygiene

A prospective evaluation of a hypoallergenic vulvar hygiene program of 14 specific practices targeted for provoked vulvodynia. Twenty percent of the participants had a complete response; 57% had a partial response.67 A limitation was the inabililty to identify the impact of each of the strategies.

Acupuncture

A prospective study of the efficacy of acupuncture showed that participants reported significant improvement in quality of life but their pain response was not reported68.

Surgical intervention

Vestibulectomy (modified perineoplasty) is often recommended for women who have failed medical management of their provoked pain. Patients with unprovoked pain or pain lateral to Hart’s line are not considered appropriate candidates. Preoperative pain mapping in the operating room prior to induction of anesthesia is essential to outline the areas of pain.

The surgery consists of a U-shaped incision in the vestibule starting at the level of Skene’s glands or lower, carried down laterally along Hart’s line medially to the perianal skin and extended superiorly to the level of the mapped pain on the opposite side. The vestibule is dissected medially to include the hymenal remnants, and the specimen is excised. The margins between Hart’s line and the medical paraurethral and vaginal tissue are re-approximated with sutures. Some surgeons mobilize the margin of the vaginal mucosa and bring the tissue inferiorly (vaginal advancement) to suture in place over the excised area from 5-7 o’ clock. Vestibulectomy technique may also utilize the Woodruff and Parmley perineoplasty,69 or a modified vestibulectomy developed by Goetsch, limiting the excision to the posterior fourchette.70

A 2008 Medline review of 38 treatments for provoked pain showed that surgery is the most efficacious (61%-94%) treatment to date, with six retrospective studies, six prospective studies, and two modified vestibulectomy studies showing similar positive results.71 Bornstein and Abramovici in randomized clinical trials compared efficacy of total perineoplasty with excision of the anterior vestibule with partial perineoplasty without excision of the anterior vestibule, but with interferon injection into the anterior vestibule. There was no significant difference in the two groups: the total perineoplasty group had a 67% complete response and the partial perineoplasty with interferon injections had a 70% complete response to treatment.72 The efficacy of interferon is not clear because there was no treatment group of partial perineoplasty without interferon injections.

Bergeron’s randomized clinical trial73 cited above (CBT) compared vestibulectomy with biofeedback and CBGT. Surgery yielded pain reduction two times higher (68%) than the behavioral treatments. No behavioral treatment worsened the pain, but in the surgical group, 9% had worsened pain by the time of follow-up.

The surgical treatment studies have methodological deficiencies. Besides the limitations of no controls or comparison groups in the majority of the studies, only the two cited above are randomized. Other weaknesses include a lack of a double-blind evaluation process, lack of descriptive information about the women in the sample, and no depiction of how pain was measured at baseline. Pain was evaluated subjectively without standardized tools. Follow up time periods vary between studies with no initial definition of successful outcome. Surgical technique varies, although there is currently insufficient evidence to support that any one specific vestibulectomy surgical technique is superior to another.74 Surgery is reported to have a placebo effect of 35%,75 and we know that a 40%-50% placebo effect is documented in randomized controlled trials of nonsurgical interventions for provoked vulvodynia.76 77 78

Despite the methodological weaknesses, surgery is considered a sound treatment option- albeit not a first line intervention.79 Nevertheless, it has been our experience that we are frequently able to determine a known cause of vulvar pain, especially early desquamative inflammatory vaginitis that appears to sensitize the vestibule. The need to perform vestibulectomy continues to decline for us.

Treatment of pudendal neuralgia

There are no studies of medical management in PN.

Lifestyle modification with cessation of any specific exercise that promoted pain is basic. Work environment modifications to minimize sitting are essential. A cushion to support the ischial tuberosities off the seat is helpful when sitting is necessary. It is estimated that 20-30% of patients improve with lifestyle modifications alone.80

Medications used for vulvodynia–diazepam, gabapentin and pregabalin (Treatment)–are used. Physical therapy to the pelvic floor (Annotation L: The Pelvic Floor) may also be of value, particularly if the therapist is able to identify muscle abnormalities or trigger points. Its main purpose is to relax pelvic floor muscles that may contribute to pain.

Pudendal nerve blocks are both diagnostic and therapeutic. Good evidence is lacking, but the block has been shown of value in small studies. In a group of 26 women a series of five CT-guided blocks at the ischial spine over a five month period yielded a 62% reduction in pain.81 In a prospective study of 55 patients, 87% had good to excellent outcomes.82 In a recent study by Fannuci et al.,83 27 patients with pudendal neuralgia underwent CT guided pudendal nerve blocks. At 1-year follow-up, 92% showed continued clinical improvement.

For unprovoked pain unresponsive to medical management, evaluation for entrapment of the pudendal nerve may be pursued.84 The nerve may tested for delays in conduction; if abnormality is present, successful relief of pain by pudendal block may lead to surgery to release entrapment. There are four described approaches to surgical decompression of the pudendal nerve. All surgical methods involve neurolysis to eliminate the possible source of compression. The trans-gluteal approach is currently the most common and successful approach for pudendal neurolysis.85 This procedure was originally described by Professor Roger Robert from Centre Hospitalier Universitaire in Nantes, France. In a sequential, randomized, controlled trial, 71.4% of the surgery group compared with 13.3% of the non-surgery group had improved at 12 months.86

Treatment of hyperpathic itching

The complexity of pruritus often requires a combination of systemic and topical therapies, using those medications that are used for vulvodynia. The topic is not well studied. (treatments above).

References

- Bohm-Starke N. Medical and physical predictors of localized provoked vulvodynia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010 Dec;89(12):1504-1510.

- Lonky NM, Edwards L, Gunter J, Haefner HK. Vulvar pain syndromes. OBG Management. 2011; 23(10):29-41.

- Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82-88.

- Andrews JC. Vulvodynia interventions- systematic review and evidence grading. Obstet Gynecol Survey 2011:66(5):299-315.

- Mandal D, Nunns D, Byrne M, McLelland J, Rani R, Cullimore J, et al. Guidelines for the management of vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2010 Mar 16.

- Danby CS, Margesson LJ. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of vulvar pain. Dermatol Ther. 2010 Sep;23(5):485-504.

- Zolnoun DA, Hartmann KE, Steege JF. Overnight 5% lidocaine ointment for treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 102(1):84-87.

- Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, Watts A, Oakes D, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116(3):583-593.

- Danielsson I, Torstensson T, Brodda-Jansen G, Bohm-Starke N. EMG biofeedback versus topical lidocaine gel: a randomized study for the treatment of women with vulvar vestibulitis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006; 85:1360.

- Boardman LA, Cooper AS, Blais LR, Raker CA. Topical gabapentin in the treatment of localized and generalized vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 112:579-585.

- Andrews JC. Vulvodynia interventions- systematic review and evidence grading. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2011:66(5):299-315.

- Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Weitz MV, et al. Cromolyn cream for recalcitrant idiopathic vulvar vestibulitis: results of a placebo-controlled study. Sex Transm Inf. 2001; 77:53-57.

- Bornstein J. Efficacy study of topical application of nifedipine cream to treat vulvar vestibulitis. J Lower Gen Tract Dis. 2009; 13:S1-S28.

- Murina F, Radici G, Bianco V. Capsaicin and the treatment of vulvar vestibullitis syndrome: a valuable alternative? Med Gen Med. 2004; 6:48.

- Steinberg AC, Oyama IA, Rejba AE, et al. Capsaicin for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 192:1549-1553.

- Kamdar N, Fisher L, MacNeill C. Improvement in vulvar vesibulitis with Montelukast. J Reprod Med. 2007; 52:912-916.

- Munday PE. Treatment of vulval vestibulitis with a potent topical steroid. Sex Transm Infect. 2004; 80:154-155.

- Morrison GD, Adams SJ, Curnow JS, et al. A preliminary study of topical ketoconazole in vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Dermatolog Treat. 1996; 7:219-221.

- Abbott JA, Jarvis SK, Lyons SD, Thomson A, Vancaille TG, Botulinum toxin type A for chronic pain and pelvic floor spasm in women. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:915-923.

- Andrews JC. Vulvodynia interventions- systematic review and evidence grading. Obstet Gynecol Survey 2011:66(5):299-315.

- Gunter J, Brewer A, Tawfik O. Botulinum toxin A for vulvodynia: a case report. J Pain. 2004; 5:238-240

- Yoon H, Chung WS, Shim BS. botulinu toxin A for the management of vulvodynia. Intl J Impotence Res. 2007; 19:84-87.

- Murina F, Tassan P, Roberti P. et al. Treatment of vulvar vestibulitis with submucous infiltrations of methylprednisolone and lidocaine. An alternative approach. J Reprod Med 2001; 46(8):713-716.

- Segal D, Tifneret H, Lazer S. Submucous infiltration of betamethasone and lidocaine in the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003; 107:105-106.

- Bornstein J, Pascal B, Abramovici H. Treatment of a patient with vulvar vestibulitis by intramuscular interferon beta: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Bio. 1991; 42:23709.

- Bornstein J. Pascale B, Abramovici H. Intramuscular beta-interferon treatment for severe vulvar vestibulitis. J Reprod Med. 1993; 38:117-120.

- Rapkin AJ, McDonald JS, Morgan M. Multilevel local anesthetic nerve blockade for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198:41.e1.

- Lonky NM, Edwards L, Gunter J, Haefner HK. Vulvar pain syndromes. OBG Management. 2011; 23(10):29-41.

- Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, Watts A, Oakes D, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116(3):583-593

- Lonky NM, Edwards L, Gunter J, Haefner HK. Vulvar pain syndromes. OBG Management. 2011; 23(10):29-41.

- Dharmshaktu P, Tayal V, Kalra BS. Efficacy of antidepressants as analgesics: a review. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Jan;52(1):6-17.

- Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, Watts A, Oakes D, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116(3):583-593.

- Brown CS, Wan J, Bachman G, Rosen R. Self-management, amitriptyline, and amitriptyline plus triamcinolone in the management of vulvodynia. J Women Health (Larchmt). 2009; 18(2):163-169.

- Reed BD, Caron AM, Gorenflo DW, Haefner HK. Treatment of vulvodynia with tricyclic antidepressants: efficacy and associated factors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2006; 10(4):245-251.

- Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ. Serotonin syndrome. Presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000; 79:201.

- Boyer EW. Serotonin syndrome. In: UpTo Date. Basow DS (Ed). UpToDate, Waltham MA, 2012.

- Wolfe F, Cathey MA, Hawley DJ. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of fluoxetine in fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994; 23:255.

- Arnold LM, Hess EV, Hudson JI, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002; 112:191.

- Patkar AA, Masand PS, Krulewicz S, et al. A randomized, controlled, trial of controlled release paroxetine in fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2007; 120:448.

- Nishikai M, Akiya K. Fluvoxamine therapy for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003; 30:1124.

- Anderberg UM, Marteinsdottir I, von Knorring L. Citalopram in patients with fibromyalgia–a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Pain. 2000; 4:27.

- Nørregaard J, Volkmann H, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. A randomized controlled trial of citalopram in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain. 1995; 61:445.

- Dworkin RH, O’Connnor AB, Backonia M, Farrar JT, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007; 132(3):237-251.

- Grothe DR, Scheckner B, and Albano D, “Treatment of Pain Syndromes With Venlafaxine,” Pharmacotherapy, 2004, 24(5):621-629.

- Dworkin RH, O’Connnor AB, Backonia M, Farrar JT, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007; 132(3):237-251.

- Magnus L. Nonepileptic uses of gabapentin. Epilepsia. 1999;40 Suppl 6:S66-72; discussion S3-4.

- Ben-David B, Friedman, M. Gabapentin therapy for vulvodynia. Anesth Anal. 1999;89:1459-1462.

- Harris G, Horowitz B, Borgida A. Evaluation of gabapentin in the treatment of generalized vulvodynia, unprovoked. J Reprod Med. 2007; 52:103.

- Andrews JC. Vulvodynia interventions- systematic review and evidence grading. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2011:66(5):299-315.

- Johannessen Landmark C. Antiepileptic drugs in non-epilepsy disorders: relations between mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(1):27-47

- Mandal D, Nunns D, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 162:1180-1185.

- Bornstein J, Livnat G, Stolar Z, et al. Pure versus complicated vulvar vestibulitis: a randomized trial of fluconazole treatment. Gynecol Obstet Invest .2000; 50:194-197.

- Rogalski MJ, Kellog-Spadt S, Hoffman AR, et al. Retrospective chart review of vaginal diazepam suppository use in high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010; 21:895-899.

- Bohm-Starke N, Falconer C, Rylander E, Hilliges M. The expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase indicates no active inflammation in vulvar vestibulitis. Acta Obstet gynecol Scand. 2001; 80:638-644.

- Hermanns K, Junker U, Nolte T. Prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone in the treatment of neuropathic pain – results from a large observational study. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012 Feb;13(3):299-311.

- Bajwa ZH, Smith HS. Overview of the treatment of chronic pain. In: UpToDate, Basow DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham MA, 2012.

- Duhmke RM, Cornblath DD, Hollingshead JR. Tramadol for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; CD003726.

- Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Tunks E. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ 2006; 174:1589.

- www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsfor HumanMedicalProducts/ucm213264 (Accessed on July 16, 2008).

- Another once-daily formulation of tramadol (Ryzolt). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2010; 52:39.

- Hassett AL, Gevirtz RN. Nonpharmacologic treatment for fibromyalgia: patient education, cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, and complementary and alternative medicine. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009; 35 (2): 393–407.

- Landry T, Bergeron S, Dupuis MJ, Desrochers G. The treatment of provoked vestibulodynia: a critical review. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(2):155-171.

- Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001; 91:297-306.

- ter Kuile MM, Weijenborg PT. A cognitive-behavioral group program for women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome (VVA): factors associated with treatment success. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006; 32:199-213.

- Kandyba K, Binik YM. Hypnotherapy as a treatment for vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a case report. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003; 29:237-242.

- Pukall CF, Kandyba K, Amsel R, et al. Efficacy of hypnosis for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a preliminary investigation. J Sex Med. 2007; 4:417-425.

- Fowler RS. Vulvar vestibulitis: response to hypocontactant vulvar therapy. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2000;4:200-203.

- Danielsson I, Sjoberg I, Ostman C. Acupuncture for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis: a pilot study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001; 80:437-444.

- Woodruff JD, Parmley TH. Infection of the minor vestibular gland. Obstet Gynecol. 1983; 62:609-612.

- Goetsch MF. Simplified surgical revision of the vulvar vestibule for vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 174:1701-1705.

- Landry T, Bergeron S, Dupuis MJ, Desrochers G. The treatment of provoked vestibulodynia: a critical review. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(2):155-171.

- Bornstein J, Abramovici H. Combination of subtotal perineoplasty and interferon for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1997; 44:53056.

- Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001; 91:297-306.

- Andrews JC. Vulvodynia interventions- systematic review and evidence grading. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2011:66(5):299-315.

- Daniels J, Gray R, Hills RK, et al on behalf of the LUNA Trial Collaboration. Laparoscoic uterosacral nerve ablation for alleviating chronic pelvic pain- a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009; 302:955-61.

- Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, Watts A, Oakes D, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116(3):583-93.

- Nyirjesy, P, Lev-Sagie A, Mathew L, Culhane JF. Topical amitriptyline-baclofen cream for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia. J Low Gen Tract Dis. 2009; 13(4):230-236.

- Petersen CD, Giraldi A, Lundvall L, et al. botulinum toxin type A- a novel treatment for provoked vestibulodynia? Results from a randomized, placebo controlled, double blinded study. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2523-2537.

- Landry T, Bergeron S, Dupuis MJ, Desrochers G. The treatment of provoked vestibulodynia: a critical review. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(2):155-171.

- Hibner M, Castellanos M, et al. Pudendal neuralgia. Glob libr women’s med, (ISSN:1756-2228) 2011; DOI 10 3843/GLOWM.10468

- McDonald JS, Spigos DG. Computed tomography–guided pudendal block for treatment of pelvic pain due to pudendal neuropathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:306–309.

- Filler A. Diagnosis and management of pudendal nerve entrapment syndromes: impact of MR neurography and open MR-guided injections. Neurosurg Q. 2008;18: 1–6.

- Fanucci E, Manenti G, Ursone A, et al. Role of interventional radiology in pudendal neuralgia: a description of techniques and review of the literature. Radiol Med. 2009;114(3):425-36.

- Robert R, Labat J, Bensignor M, et al. Decompression and transposition of the pudendal nerve in pudendal neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial and long term evaluation. Eur Urol. 2005;47(3):403-408.

- Hibner M, Castellanos M, et al. Pudendal neuralgia. Glob libr women’s med, (ISSN:1756-2228) 2011; DOI 10 3843/GLOWM.10468

- Robert R, Labat JJ, Bensignor M, Pascal G, Deschamp C, Raoul S, Olivier H. Decompression and transposition of the pudendal nerve in pudendal neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial and long-term evaluation. European Urology. 2004;47(3):403-408.