Annotation N: The vaginal architecture

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationEmbryology

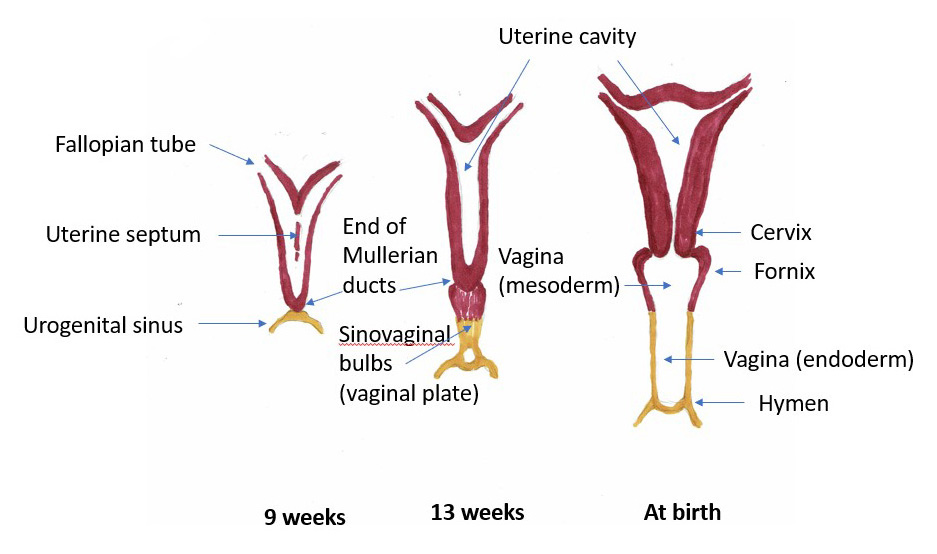

The vagina (Latin, sheath) develops from the urogenital sinus, advancing from inferior to superior to meet the Mullerian ducts which are developing superiorly to inferiorly. The plate that their union forms canalizes to a tube with upper, middle and lower thirds of approximately the same length but with different innervation and blood supply. (For an excellent, easy to understand video on this process, take a look at Dr Minass’s video on Embryology of the Female Reproductive System on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmK1XYVm8xM).

Embryological development of the internal female genitalia

Anatomic Structure

The vagina is the conduit between the uterine cervix and the vulvar vestibule. The hymen, essentially the doorway from the external vulvar vestibule to the vagina, is a membrane of connective tissue covered on both sides by stratified squamous epithelium, that extends from the floor of the urethra to the fossa navicularis of the vestibule to partially occlude the vaginal orifice. At the interface of the introitus and the vagina, the hymen marks where the urogenital sinus (perineum) meets the vaginal canal, a mullerian structure.

Depending on rectal and bladder contents, the vagina forms a 90 degree angle with respect to the uterine axis, ascending posteriorly and superiorly. This fibromuscular tube has anterior, posterior and lateral sidewalls. The anterior and posterior walls are slack and are in contact with each other. The lateral walls are more rigid and remain separate. This creates, in cross-section, an H-shaped appearance.1

On average, the vagina measures 8-8.5 cm from the hymenal ring to the top of the anterior fornix (Latin, arch or vault), 7-7.5 cm to the top of the lateral fornices and 9-9.5 cm to the top of the posterior fornix. Length of the vagina is generally measured from the hymenal ring to the posterior vaginal fornix, as that length is most impacted by pathology.2

In the upper third of the vagina, the anterior wall is closely applied to the bladder, separated only by loose areolar tissue. Inferior to the bladder, the urethra and clitoral bodies are embedded into the anterior vaginal wall for most of its length. The posterior aspect of the upper third of the vagina is covered with peritoneum of the cul-de-sac, creating direct access to the peritoneal cavity at this point.

The middle third of the vagina is covered posteriorly by fibrofatty tissue, the rectovaginal septum and then the rectum.

In the lower third of the vagina, the rectovaginal septum and the muscles of the perineal body separate the body of the vagina from the anus. The lower lateral walls of the vagina touch the pelvic fascia and the levator ani muscles.3

Innervation of the vagina is complex and not well studied, although there are both sensory and autonomic nerve fibers identified. The autonomic nervous system’s vaginal plexus contributes to the autonomic nerve supply of the vagina, while the sensory nerve fibers come from the pudendal nerve. The anterior vaginal wall has more nerve fibers than the posterior and the upper portion of the vagina is less well enervated than the lower third.

Blood supply of the vagina is rich. The upper and middle thirds are supplied by branches of the vaginal artery originating from the hypogastric (internal iliac) artery. The dorsal clitoral arteries, originating from the internal pudendal artery, supply the distal vagina where it is adherent to the urethra and the clitoral bulbs.4

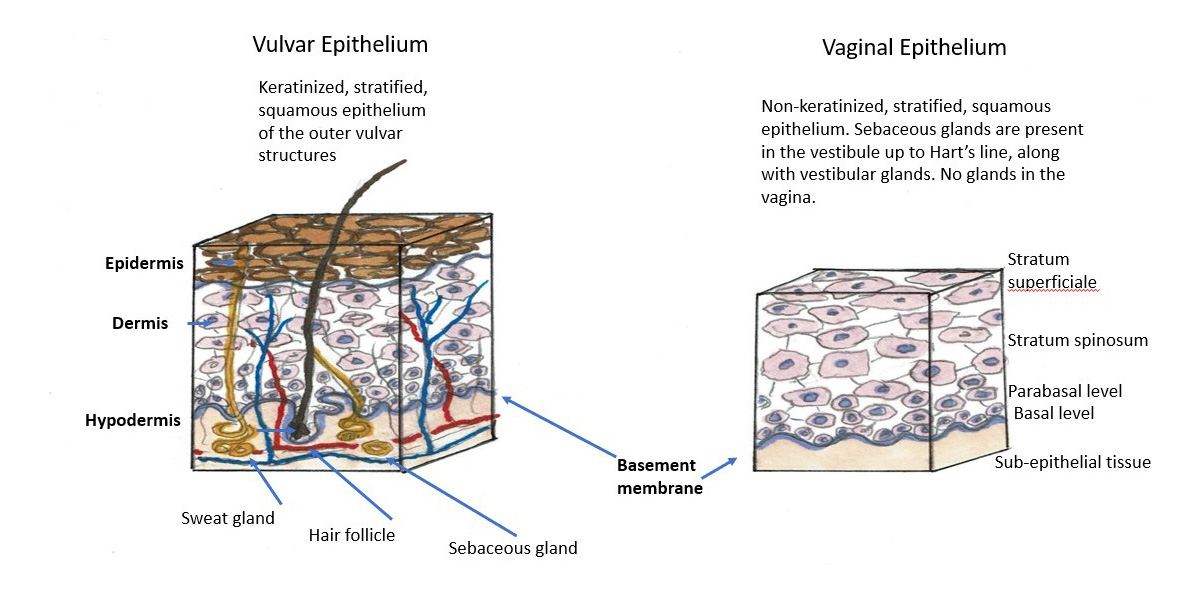

Histology

The vagina is composed of four layers: (1) inner layer of non-keratinized squamous epithelium containing no glands; (2) the lamina propria, rich in elastic fibers; (3) the muscularis layer of smooth muscle with inner circular surrounded by outer longitudinal layers, and (4) the adventitial layer, which merges with the adventitial layers of the bladder and the rectum. The entire vaginal wall thickness measures 2-3 mm in a reproductive age woman but is usually thinner when estrogen levels are lower.

The epithelial layer is composed of a lower basal layer, several layers of parabasal cells and multiple layers of intermediate and superficial squamous cells that progressively accumulate glycogen. Transverse epithelial folds dip into the third layer of muscularis and contribute to the elasticity of the vaginal walls, allowing intercourse and childbirth.

Physiology

The vagina, like the uterus and the bladder, is estrogen sensitive. The estrogen acts on receptors in the vagina to maintain the collagen content of the epithelium. Estradiol maintains acid mucopolysaccharides and hyaluronic acid, keeping the epithelial surfaces moist and well glycogenated and optimizing genital blood flow.

The surface cells of the vagina are cast off into the vaginal canal. This desquamation goes on constantly and the epithelium is replenished by mitotic division of cells in the basal layer. Using the glycogen from epithelial cell breakdown and glucose from transudation as energy sources, bacteria of the Lactobacillus genus thrive. The bacterial breakdown of glycogen and glucose into lactic acid serves to acidify the vagina.

The vagina contains no glands and is moisturized by transudation and mucus secreted from the cervix and the paraurethral, vestibular, and Bartholin’s glands, all in close proximity.5

Vaginal pH, ecosystem, and wet preps are discussed in Annotation P. Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy and other testing.Annotation P

Introduction

Architectural abnormalities of the vagina are diverse; time of presentation varies from birth to postmenopause. Many are asymptomatic and are detected by careful speculum examination; others present with pain, dyspareunia, or vaginal bleeding.

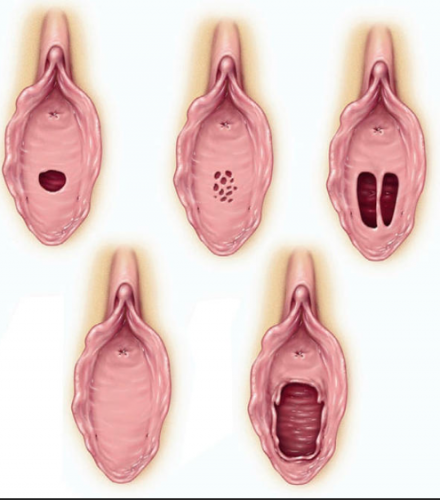

The hymen and its variants

The hymen (Latin, veil), the anatomical doorway to the vagina, is located at the interface of the introitus and the vagina, marking where the urogenital sinus (perineum) meets the vaginal canal. Usually a thin fibrous tissue membrane, in some women the membrane may be thicker and manifest with an anatomic variant, including imperforate hymen and incomplete hymenal fenestration (e.g. microperforate, septate, and cribiform hymens). Usually it has, for the exit of menstrual flow, one or more openings as depicted below.

Top row, left: normal virginal hymen. Top row, middle: cribriform hymen. Top row, right: septate hymen. Bottom row, left: imperforate hymen. Bottom row, right: ruptured hymen.

The elasticity of the hymen varies. Typically, with the introduction of a penis, finger, tampon, or sexual device, the opening stretches and becomes larger. The hymen may be avulsed by examination, trauma, surgery, or coitus. While there is a popular belief that gymnastics, horseback riding, and other vigorous sports can rupture the hymen, no relation between sports and hymenal changes was found in a study of three hundred females.6 Despite the sociocultural significance of the hymen in certain communities,7 examination of the hymen can not reveal whether or not sexual penetration, either consensual or nonconsensual, has taken place.8 The hymen may have normal tags, ridges, bands, and notches, and bleeding does not always occur with penetration. There is no “standard” appearance of the hymen for females of any age. Forceful penetration may cause abrasions or bleeding not relevant to the hymen.9

The vascular supply of the hymen is rich, but the membrane is usually thin. Multiple capillaries reach the superficial layer of the epithelium.10 The vascularity is the cause of the severe bleeding which occasionally accompanies hymenal rupture. However, there may be no bleeding with first penetration.11

The hymen is not richly supplied with nerve fibers throughout its surface. The free border of the hymen has none in order to facilitate painless intromission, while the attached border is relatively rich in nerve fibers.12

The function of the hymen is not clear, but is thought to include innate immunity as it provides a physical barrier to infections during the pre-pubertal period when the vaginal immunity is not fully developed.13

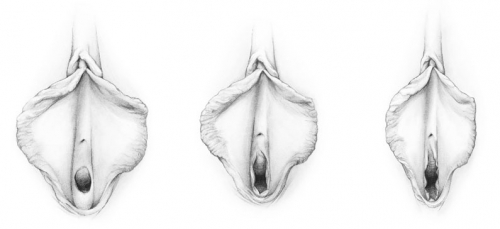

After penetration, rupture, or childbirth, the hymen does change in appearance:

Hymen before penetration, after penetration, and after childbirth (drawing by Dawn Danby from The V Book by Elizabeth G. Stewart, MD)

Exam of the hymenal ring or remnants in routine evaluation of vulvovaginal complaints is covered in Annotation L: Exam of the hymenal ring and the pelvic floor.

Imperforate hymenal ring

Prevalence: uncommon, estimated about 0.5/1000 females

Etiology: Thought to be caused by the failure of the central portion of the hymen to be perforated during the embryonic stage of development.

Symptoms and clinical features

Some cases of imperforate hymen are identified shortly after birth if a bulging introitus is noted in the early neonatal period. There are also some reported cases of diagnosis before birth based on ultrasound findings.14 The bulging is related to the retention of vaginal secretions due to the high estrogen state of intrauterine life. Most commonly, the mucus will resolve and further problems will not occur until puberty. Rarely, there is associated ureteral obstruction which may be associated with urinary tract infections, hydronephrosis or even respiratory distress. In these situations, prompt treatment in the neonatal period is required.15 The condition may also arise from an inflammatory reaction such as lichen sclerosus affecting the hymen after birth.16

More commonly, diagnosis is made at the time of puberty, when the patient presents with hematocolpos. The most frequent presenting symptom is abdominal pain, although many also have genitourinary symptoms including urinary retention, dysuria and urinary frequency. Primary amenorrhea (also called cypto-menarche) is present.17

Diagnosis

A physical examination is the first step. If a bulging hymen is noted and transabdominal, translabial or rarely transrectal ultrasound is consistent with hematocolpos with a thin membrane, no further imaging is needed. Confusion with low transverse vaginal septum or even vaginal agenesis can occur, so a purely clinical diagnosis without imaging is not advised.18

Treatment

Most imperforate hymens are treated surgically. There are some reported cases of diagnosis in the neonatal period with resolution spontaneously prior to menarche.

Ideal timing for the procedure is in the postpubertal but still premenarchal time, when the patient has had no symptoms but estrogen stimulation has already occured, which facilitates the repair.

The majority of surgical repairs are done by hymenotomy, usually a cruciate or elliptical incision in the hymen. This can be done with scalpel, laser, or electrocautery with excellent cosmetic results usually noted. Some physicians prefer hymenectomy. Additionally, some will surgically incise in only one direction and insert a foley catheter through the incision into the vagina for about 2 weeks. This allows preservation of most of the hymen and will generally result in bleeding at the time of loss of virginity. This may be considered as an option for those for whom this is an important cultural preference.19

Surgical complications of hymenotomy may include formation of vaginal adhesions or closure of the incision. Infection may occur, although uncommon with these procedures.

Incomplete hymenal fenestration

Prevalence

Uncommon, although likely more common than imperforate hymen

Etiology

As with imperforate hymen, incomplete opening of the hymen in the gestational period

Symptoms and clinical features

Incomplete fenestration is very variable in presentation, depending on the size of the opening(s) through the hymen. Some women present with difficulty inserting or removing tampons or vaginal inserters. Others present with inability to achieve vaginal penetration during sex, usually due to pain and tissue resistance.

For those with smaller perforations, malodorous discharge may be the presenting symptom due to partial occlusion of drainage. Rarely, pelvic infection can follow from the retained menstrual products.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can usually be established with a clinical exam. If the hymenal perforations are sufficiently large to allow visualization of normal vaginal anatomy above the hymen, no imaging is required,

Treatment

Surgical treatment is standard. For the microperforate or otherwise almost complete hymen, hymenotomy is done similarly to the procedure for imperforate hymen (elliptical, cruciate or u-shaped incision). For those with less hymenal tissue occluding the vaginal opening, simple excision of the excess hymenal remnants is sufficient.

Septate hymen on the left; imperforate hymen on the right

Congenital abnormalities of the vagina

Congenital abnormalities of the vagina are primarily Müllerian malformations which originate during development of the paramesonephric ducts.

There are several classification methods that may facilitate diagnosis. Most commonly in use in the USA is the classification system supported by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) but this system does not specifically focus on the vagina. Accordingly, we use the system advocated by the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE). The ESHRE/ESGE system includes 5 vaginal options:

V0 Normal vagina

V1 Longitudinal non-obstructing vaginal septum

V2 Longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum

V3 Transverse vaginal septum and/or imperforate hymen

V4 Vaginal aplasia (agenesis)20

Vaginal agenesis (V4)

Prevalence

Vaginal agenesis is estimated to occur in one in 4000 to one in 7,000 female births. Other abnormalities, such as cervical or uterine agenesis, are often identified in women with this condition.

Etiology

More than 90% of patients with vaginal agenesis have Rokitansky-Mayer-Küter-Hauser syndrome (RMKH). Women who have this condition are genetically female with 46XX chromosomes. The ovaries are usually normal but may be mislocated. External genitalia are normal. There is maldevelopment or absence of the vagina, fallopian tubes, cervix and/or uterus. There may also be associated problems with the kidneys, the skeleton and hearing. Etiology of RMKH is unknown.

The differential diagnosis includes other vaginal obstruction, such as transverse septum, discussed below. Others have androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) with 46XY chromosomes and no vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes or ovaries. External genitalia may look like those of a normal female or may have male attributes.21

Other genetic or developmental abnormalities account for the remainder of patients with this condition.

Symptoms and clinical features

Physical findings vary from complete agenesis with only a dimple demarcating the potential vaginal opening, to a short vaginal pouch. As a leading cause of primary amenorrhea, agenesis is usually detected during adolescence.

Treatment

Initial evaluation should include hormonal testing (testosterone and FSH) and karyotype testing. Translabial, transrectal, or transabdominal ultrasound imaging is essential for understanding the extent of Müllerian abnormalities. MRI may provide additional information. Afterwards, referral for discussion and management at a major medical center is indicated. The initial treatment plan usually includes primary vaginal elongation with vaginal dilation. This is effective in the majority of women. Surgical correction by creation of a neovagina is required in a minority of women.22 23

Longitudinal vaginal septum (V1, V2)

Prevalence

Rare.

Etiology

A longitudinal vaginal septum develops during embryogenesis when there is an incomplete fusion of the lower parts of the two Müllerian ducts.24 As a result, there is a double vagina. There are often associated duplications of the more cranial parts of the Müllerian derivatives, such as a double cervix, and either a uterine septum, or a uterus didelphys (double uterus). Studies are essential to rule out possible associated anomalies of the genital and urinary tract.

Symptoms and clinical features

If there is no vaginal obstruction, a woman with a longitudinal vaginal septum may be completely asymptomatic. Various clinical symptoms, such as severe dysmenorrhea, lower abdominal pain, paravaginal mass, excessive, foul, mucopurulent discharge, and intermenstrual bleeding, which are dependent on the existence of uterine or vaginal communications, may also be present.25

In a small percent of cases, there can be an obstructed hemivagina associated with ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA), also known as Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome.

Evaluation

Careful pelvic examination and ultrasound are the first components of evaluation. If the OHVIRA is suspected with a patent distal vagina, palpable cervix and lateral bulging of the vagina, an MRI is also usually obtained to assist with surgical planning.26

Treatment

Referral to an experienced gynecologist for evaluation for resection is recommended. Many asymptomatic women may choose no treatment.

For those with an obstructed septum or significant symptoms, surgery is indicated. The traditional surgical method requires transvaginal resection of the obstructed septum, and continues to be the most widely used approach. However, this conventional excision requires hymenal disruption and wide exposure of the vagina, and can be technically difficult, especially in adolescent virgins.27

Hysteroscopic (vaginascopic) resection of an obstructed septum is simple and fast, and does not require any specialized surgical technique. Hysteroscopy preserves hymenal integrity, and facilitates intervention as it considerably enlarges the surgical view. In addition, transabdominal ultrasound guidance improves interventional accuracy.28

Additionally, a laparoscopic approach has been reported for those with other associated abnormalities that may necessitate further evaluation or treatment.29

Transverse vaginal septum (V3)

Prevalence

Rare

Etiology

A transverse septum can form during embryogenesis when the Müllerian ducts fuse improperly to the urogenital sinus. Incomplete canalization of the vagina occurs.30

Symptoms and clinical features

A transverse septum may occur at any level of the vagina, upper, middle, or lower aspect. The septum is usually 1 cm or less in thickness. The majority have a small perforation (not always in the middle) and thus are not completely obstructive. The perforated septum may be diagnosed after presentation for symptoms such as dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia.

A complete transverse septum will block menstrual flow and is a cause of primary amenorrhea. The accumulation of menstrual debris behind the septum is termed cryptomenorrhea.31

These disorders usually present at puberty with primary amenorrhea and the cyclic pain of hematocolpos. The main differential diagnosis in this case is imperforate hymen. Examination will usually allow clinical differentiation as the speculum exam and bimanual exam will reveal an obstructing lesion partway up the vaginal canal.

Additional evaluation is necessary for surgical planning, which may include ultrasound or MRI. A recent report has suggested saline infusion sonocolpography with ultrasound.32

Treatment and outcomes

Surgical excision is recommended. This condition is usually approached vaginally, with resection by scalpel, laser or cautery. Vaginoscopy resection with hysteroscopy instruments has also been reported as a successful approach.33

Postoperatively, most women will be advised to use vaginal dilators to help to maintain vaginal patency and to avoid stenosis. In one small study of 46 patients, 11% presented with repeated obstruction, 7% with vaginal stenosis. Postoperative questionnaires returned by the patients revealed that 35% had dyspareunia and 36% had dysmenorrhea.34

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure

Additional information about DES is available in Annotation M: Speculum exam and examination of the cervix. Information about vaginal adenosis, often related to DES, is available in Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium .

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was prescribed to pregnant women for the prevention of miscarriage after its synthesis in 1938 until after 1971 when the association of DES with clear cell carcinoma of the vagina was reported.35 The medication was still administered for some other purposes (e.g. postcoital contraception, lactation suppression) for some additional years, so some DES pregnancy exposure occurred in the US at least through 1975.

In utero exposure to DES has been associated with some architectural changes of the cervix and the vagina. In the vagina, this may include vaginal ridges and transverse vaginal septa.

Prevalence

Approximately 5 million women worldwide were exposed to in utero DES. Cervical or vaginal changes are noted in approximately 20% of exposed women.36

Symptoms and clinical features

Vaginal architectural changes are rarely symptomatic.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by clinical appearance in a woman with known or suspected DES exposure.

Treatment

Treatment of the architectural changes is rarely needed except in the rare case of a transverse vaginal septum (see section on transverse vaginal septum, above).

Congenital vaginal cysts

Introduction

A vaginal cyst is a closed sac containing fluid or semisolid material located on or under the vaginal epithelium. A vaginal cyst can be either congenital (an embryological derivative) or acquired. Many cysts are asymptomatic but some will present with pain, dyspareunia, urinary symptoms, bleeding or other significant symptoms, ectopic tissue, or a urologic abnormality. Benign vaginal cystic lesions can range in size from the size of a pea, to the size of an orange, large enough for urological obstruction.

Most studies show that Müllerian cysts are the most common vaginal cysts, comprising 30-44% of vaginal cysts 37 38 Acquired vaginal inclusion cysts are next in frequency, followed by Gartner’s duct cysts. A variety of uncommon cysts may also occur, including urethral diverticuli, and endometriotic cysts.

Müllerian vaginal cysts

Prevalence

Relatively common, with estimated incidence of 1/200 women; this is an estimate, as many vaginal cysts are asymptomatic incidental findings.39

Etiology

Persistent glandular remnants from embryonic development, usually paramesonephric duct residue.

Symptoms and clinical features

Although these cysts are usually asymptomatic when smaller, the larger ones may present with pressure and/or sensation of fullness in the vagina. The cysts may occur in any area of the vagina and range from 0.5 cm to 7 cm. Histology usually shows a mucinous endocervical type epithelium. Occasionally the cysts will be lined with cells with the appearance of cells from the fallopian tube or endometrium. The diagnosis can be confusing if the cells are more cuboidal. In that case, a mucicarmine stain for mucus will help identify the Müllerian cyst (positive result) from one of mesonephric origin (negative result).40 41

Diagnosis

Clinical assessment is an important component of diagnosis. Müllerian cysts are usually soft and easily compressible. If the cyst is asymptomatic, small, and bland appearing, no further investigation is required. Otherwise, transvaginal ultrasound is the first step in evaluation (warn the radiologist that the concern is the vagina). An MRI may be of value for a large cyst or in pre-surgical planning.

Treatment

The majority of small asymptomatic cysts may be followed clinically with observation annually. If symptomatic or enlarging, excision is recommended.

Gartner’s duct cysts

Prevalence

Less common, making up 10-25% of reported vaginal cysts

Etiology

Gartner duct cysts, also known as mesonephric cysts, arise from the vestigial remnants of the mesonephric ducts. Due to this origin, they may extend into the broad ligament and near the ureter. Other genitourinary malformations may be associated with Gartner duct cysts, including ipsilateral renal agenesis and ectopic ureter. 42

Pathologically, the mesonephric cysts are lined with a nonmucinous cuboidal or low-columnar epithelium. There may be smooth muscle around the cyst, but this is not consistently found.43

Symptoms and clinical features

Although Gartner’s duct cysts may occasionally be identified in the newborn period, the peak age is 31-40. Gartner’s cysts are often small, <2 cm. They can be multiple. The cysts are usually located in the anterolateral vaginal wall. The majority of Gartner duct cysts are asymptomatic and identified as an incidental finding on pelvic exam. Occasional women will have symptoms associated with the size of the cysts. They may present in adolescence as an obstruction to tampon insertion or as dyspareunia.

When the cysts enlarge, they may be mistaken for other structures, such as anterior vaginal wall prolapse (cystocele) or urethral diverticulum. 44 The largest Gartner duct cyst reported measured 16 cm x 15 cm x 8 cm. 45Large cysts can cause dyspareunia or interfere with normal vaginal delivery.46

Treatment

Observation with annual examinations is recommended for stable, asymptomatic cysts. If symptoms or enlarging size require intervention, they can be excised, although it may be safer to simply marsupialize deep cysts to avoid significant bleeding.

In view of the association with other urogenital malformations and possibility of deep extension into the broad ligament, imaging is indicated prior to excision of a vaginal wall mass, usually with MRI.

Acquired vaginal structural changes

Vaginal inclusion cyst

Prevalence

Common, making up about 25% of vaginal cysts

Etiology

These arise from inclusion, beneath the epithelial surface, of tags of mucosa resulting from perineal lacerations or from imperfect approximation during surgical repair of the perineum, usually after delivery, hysterectomy, or other trauma. Female genital mutilation surgery has also been reported as associated with increase in vaginal (as well as vulvar) inclusion cysts.47

Symptoms and clinical features

Vaginal inclusion cysts are common near the introitus, but may be found anywhere in the vagina depending on the initiating trauma. They are lined by a stratified squamous epithelium, and the content is usually cheesy or clear. Size is variable but it is uncommon to exceed 1.5 cm in size.

Many women are asymptomatic. The cysts may be found incidentally on exam or the patient may point it out wanting a diagnosis. Uncommonly the cysts can be tender or painful.

Treatment

Vaginal inclusion cysts do not require excision unless they produce discomfort.

Urethral diverticula

Prevalence

The reported prevalence of urethral diverticula ranges from 1 to 5 percent of adult females.48 The true prevalence may be higher, since accurate diagnosis of diverticula is difficult.

Etiology

The etiology of urethral diverticula is not clearly understood, although it is generally thought that the condition is acquired, not congenital.49 A widely accepted theory suggests repeated infection with E. coli, gonococcus, and chlamydia in the periurethral glands leads to obstruction and formation of a suburethral abscess. If the abscess ruptures into the urethral lumen, a communication between the abscess cavity and the urethra develops. Fibrosis and adhesion to adjacent structures follow.50

Other possible causes include trauma from childbirth, or vaginal or urethral surgery, including repetitive transurethral surgical procedures. Urethral diverticula have now been reported after the tension-free vaginal tape sling procedure and transurethral collagen injection.51 52

Symptoms and clinical features

While anterior wall masses may be vaginal wall cysts, urethral diverticula are more common in the distal two thirds of the urethra at this location, and can often be palpated. The symptoms of urethral diverticulua have been historically described as a classic triad of three D’s: Dysuria, Dyspareunia, and Dribbling, but these symptoms are present in about one third of cases.53 Diverticula can be asymptomatic, may be incidentally detected, or may present with painful vaginal mass, chronic pelvic pain, or recurrent urethritis or cystitis.54 In a significant percentage of women, there are nonspecific symptoms.55

Diagnosis

The best choice for imaging studies is controversial. Some clinicians will start with ultrasonography due to availability and reasonable cost. Ultrasound is, however, operator dependent.56 MRI is the most sensitive study for diagnosing diverticula but again requires radiologist expertise in this area.57 Previously, voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) had been used to identify a urethral diverticulum, but is no longer recommended because of its low sensitivity.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of urethral diverticulum includes vaginal wall inclusion cyst, Skene’s gland abscess, Gartner’s duct cyst, ectopic ureterocele, periurethral fibrosis, urethrocele, vaginal leiomyoma, and urethral or vaginal neoplasm.58

Treatment

Surgical management remains the treatment of choice, although expectant observation may be appropriate for women with few or no symptoms and when malignancy is not suspected. Surgical management is generally performed by a urologist or urogynecologist.

Vaginal endometriosis

Prevalence

Endometriosis in the vagina is rare.

Etiology

Vaginal endometriosis is the ectopic implantation of endometrial glands and stroma in the vagina; it is thought to occur by implantation after surgery or procedures such as endometrial curettage. Extra-pelvic lesions are reported in women with no history of endometriosis and in the absence of prior surgery, with pathogenesis presumed to be vascular or lymphatic migration, cellular metaplasia, and iatrogenic metastasis.59

Symptoms and clinical features

Many patients with pelvic endometriosis have nodules palpable through the posterior vaginal fornix. Rarely, the disease may extend into the vaginal vault, especially after hysterectomy, causing red-blue to yellow-brown nodules visible on speculum examination and palpable in the posterior fornix. Presentation with a tender mass, cyclic pain with menses, or continuous bleeding may also occur.

Diagnosis

Biopsy must show two of the three: endometrial glands, stroma, hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Foreign body giant cells may be found.60

Differential diagnosis

Melanoma, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, squamous cell carcinoma

Treatment

Excisional biopsy is the usual treatment.61

Benign solid vaginal masses

Vaginal fibroepithelial polyp

Prevalence

Originally thought to be uncommon, more recent literature suggests that fibroepithelial polyps of the vagina are not unusual, although less frequently identified than cervical/endocervical polyps.

Etiology

Vaginal fibroepithelial stromal polyps were first described in the female genital tract in 1960. They are considered to be benign masses noted for polypoid proliferation of the stroma. Overlying squamous epithelium is generally benign.62

Hormonal influences may play a role in their formation.63 Suggestive evidence includes: (1) the propensity of these lesions to occur during pregnancy and spontaneously regress following delivery; (2) the association with hormone replacement therapy in the postmenopausal patient; and (3) the stromal cells can be estrogen and progesterone receptor positive. Furthermore, fibroepithelial polyps are extremely uncommon before the menarche.64

Symptoms and clinical features

Fibroepithelial stromal polyps of the vulvovaginal region are generally asymptomatic and found on examination. Occasionally, symptoms may occur, including vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, dyspareunia or vaginal discharge, among others.65

Fibroepithelial polyps usually occur in young to middle aged women in their reproductive years, presenting more commonly in the vagina, but also occurring in the vulva and rarely the cervix.66 They can occur as a single lesion, polypoid or fronded, or can be multiple, an occurrence particularly associated with pregnancy.67 Polyps that occur during pregnancy tend to exhibit a greater degree of cellularity and nuclear pleomorphism, which in the past contributed to the use of the term ‘pseudosarcoma botryoides’ by some authors.68 These lesions are benign but have the potential for local nondestructive recurrence, particularly if incompletely excised.69

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually on the basis of clinical appearance. If there is concern about symptoms, lesion size or possible malignancy, excisional biopsy is preferred.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign polyps may be confused with a variety of uncommon pathologic entities, including angiomyxoma, cellular angiofibroma and rhabdomyosarcoma.70

Treatment

A vaginal polyp that is not enlarging or causing symptoms does not require treatment, but since it can be difficult to determine the identity of the lesion, excisional biopsy is often performed. Polyps first identified during pregnancy can spontaneously regress afterwards.71

Vaginal leiomyoma/fibroma

Prevalence

Rare, occuring most frequently in women in reproductive age, with a mean age of 40.72 Fibroma is a rare solid, usually asymptomatic, tumor that may arise de novo from the connective tissue and smooth muscle elements of the vaginal wall. Some are intraligamentary uterine fibromas which have separated from the uterus and dissected into the paravaginal area.

Etiology

Unknown, thought to be hormonally related

Symptoms and clinical features

A vaginal leiomyoma may vary in size from small (1.5 in diameter) to obstructive of the vaginal canal. It can arise anywhere within the vagina, most often on the anterior wall. Unlike a uterine myoma, the vaginal myoma is single. Dyspareunia or vaginal bleeding are possible, especially if the myoma ulcerates the overlying mucosa. Prolapse of a large myoma through the vaginal introitus can occur.73

Diagnosis

Initial diagnosis is by physical examination, often supplemented by ultrasound or, rarely, MRI. Biopsy may be considered if the diagnosis is in doubt or if leiomyosarcoma is a consideration.

Differential diagnosis

Anterior wall myoma may be confused with prolapse (cystocele), urethral diverticulum, developmental cyst, or cervical myoma. Posterior vaginal wall tumors must be distinguished from prolapse (rectocele), enterocele, inclusion cyst.74

Treatment

Small tumors can be observed if stable. Excision is appropriate if symptoms are problematic or the fibroid is growing.

Vaginal wall defects (prolapse)

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) includes descent of the cervix and uterus (not considered a vulvovaginal problem and not discussed here), and defects of the anterior, apical, and posterior vaginal wall that allow herniation of the urethra, bladder, rectum or bowel into the vagina. Prolapse is mainly a urogynecological problem but is discussed here in view of its vaginal involvement.

Anterior compartment prolapse is defined as herniation or descent of the anterior vagina. Anterior compartment defect replaces the previously used terms of cystocele and urethrocele; the current definition utilizes the actual site of vaginal wall prolapse (anterior vaginal wall), rather than the structures underlying it (bladder or urethra). Vaginal topography does not reliably predict the location of associated viscera.75

Apical compartment prolapse includes descent of the apex of the vagina into the lower segment of the vagina, to or beyond the hymen. The apex can be either the uterus and cervix, cervix alone, or vaginal vault if the woman has had a hysterectomy. Enterocele often accompanies apical prolapse.76

Posterior compartment prolapse is defined as hernia of the posterior vaginal wall usually associated with descent of the rectum. Posterior compartment defect or prolapse replaces the term rectocele since the location of the rectum cannot reliably be predicted based on vaginal topography.

Enterocele represents protrusion or herniation of the intestines to or through the vaginal wall.

Defects of pelvic support often do not occur in isolation. In a series of 384 women undergoing surgical repair of POP there were: anterior defects only (40 percent), posterior defects only (7 percent), apex only (6 percent), anterior and posterior defects (16 percent), anterior defect and apex defect (9 percent), posterior defect and apex defect (5 percent), and all three defects (18 percent).77

Prevalence

Prevalence is probably common, but difficult to assess since various classification systems have been used. In addition, prolapse is best defined by whether it is symptomatic or not, since treatment is indicated only for women with symptoms. It is unknown how many women exist with asymptomatic POP, and high quality evidence regarding symptomatic POP is limited. While 200,000 inpatient surgical procedures for prolapse are performed yearly in the USA,78 there are still many symptomatic women with POP who do not elect surgery. Estimates of prevalence of POP range from 3-11 percent of women.79

Etiology

In the past, vaginal wall defects were believed to be due to stretching or thinning of the anterior vaginal wall and its supports, thereby allowing herniation of neighboring organs into the vagina. Based on this assumption, surgical plication or tightening of the weak and redundant vaginal wall (i.e. anterior colporrhaphy) became the treatment. We now know that vaginal wall prolapse is not as simple as a stretch defect in this area, but is the result of a specific defect in the support structures of the vagina. Lack of attention to the specific defect in these support structures is a major reason that anterior vaginal wall prolapse recurs in as many as 40 percent of patients after anterior colporrhaphy alone.80

The last couple of decades have seen significant progress in our understanding of the pathophysiology and anatomy of pelvic prolapse. We now know that the pelvic organs are supported through a complex interplay between the uterosacral/cardinal ligament complex, the levator ani muscles, the endopelvic fascia, and the nervous system. These structures attach the pelvic organs to the bony pelvis and form a continuous and interdependent organ complex. Pelvic prolapse occurs, in part, due to site-specific fascial defects that result in anterior, apical, or posterior vaginal segment weakness. Damage to any of the muscles and fibrous structures results in descent of the vaginal walls and pelvic organs through the urogenital hiatus. Understanding this process has led to improvement in the surgical approach to a challenging clinical problem.81

Symptoms and clinical features

Vaginal wall defects may or may not be symptomatic. Symptoms tend to become bothersome when the prolapse extends beyond the hymenal ring,82 but severity of the symptoms does not correlate well with the degree of prolapse.83

Symptomatic women who have prolapse do not describe common vulvovaginal complaints of itching, burning, or rawness. Prolapse is not a common etiology of pain and dyspareunia. Therefore, women with irritative complaints and pain need evaluation for other causes besides prolapse.

Sexual dysfunction is, however, common as women avoid sexual activity because of fear of discomfort or embarrassment regarding bulges, or urinary or bowel incontinence during sexual activity.84 Women with POP may also have sexual dysfunction because of mechanical issues from prolapsed tissue, or difficulty with penetration because of the obstacle from protrusion of the fecal-filled rectum into the vagina.

Pelvic pain and low back pain are classically associated with POP, but well designed studies do not validate the association.85 86

Women do speak of vaginal or pelvic fullness, heaviness, pressure, or discomfort that often worsens over the course of the day. These symptoms are most noticeable after prolonged standing or straining. Patients with POP frequently describe feeling as if they are sitting on an egg.

The report that something is protruding or falling out of the vagina is common, and some women may be able to see the prolapsed tissue. Exteriorization may result in vaginal discharge; vaginal bleeding from friction and ulceration may occur.

Women with anterior vaginal wall defects may have stress urinary incontinence, incontinence with intercourse, urgency, frequency, nocturia, or enuresis.87 88 Advanced anterior vaginal compartment prolapse can cause urethral obstruction or “kinking”, resulting in slow stream, incomplete emptying, or urinary retention.89 Women may need to reduce or splint the prolapse of the anterior wall and urethra manually in order to empty their bladders.

Constipation is the most common bowel symptom associated with all types of prolapse,90 but with posterior compartment defects there may also be tenesmus, and either fecal incontinence or obstructive symptoms such as incomplete emptying and straining.91 Women with posterior compartment defects may need to apply digital pressure (splinting) to the posterior bulge in the vagina, or to the perineum, in order to move their bowels. Incontinence of stool may occur during sexual intercourse.92

Diagnosis

Pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POPQ)

In the past, prolapse has been graded in severity by several imprecise classification systems with poor reproducibility as well as poor potential for standardized communication between clinicians. These deficiencies have been replaced with POPQ, an objective, site specific system for describing and staging POP.93 A “map” of the vagina is created from quantitative measurements of points representing anterior, apical, and posterior vaginal prolapse. These anatomical reference marks are then used to determine the stage of the prolapse. The POPQ test With a brief office examination, the clinician can identify prolapse to make an appropriate referral.

Anterior compartment defects are best demonstrated with the woman in the lithotomy position. A retractor or the posterior blade of a Graves speculum is used to depress the posterior wall of the vagina. The patient is then asked to bear down, and, if present, the anterior wall bulge may be seen.

Posterior compartment defects may be identified by retracting the anterior vaginal wall upward with the blade of a Graves or Pederson speculum and again having the patient strain. If prolapse is present the rectum will bulge into the vagina. Placement of one finger in the rectum and one in the vagina allows palpation of the herniation.

Enterocele is challenging to diagnose. It represents a hernia of the peritoneal cavity along a weakened pouch of Douglas between the uterosacral ligaments and into the rectovaginal septum. It occurs frequently after abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy. If large enough, it may prolapse through the vagina. It may be palpated as a separate bulge above the posterior wall prolapse. Frequently, the diagnosis is established only at the time of surgery.94

Differential diagnosis

Anterior compartment: myoma, inflamed and enlarged Skene’s glands, urethral diverticula, bladder tumors, bladder diverticula. Differentiation of posterior compartment: herniation from enterocele as above, and myoma.

Treatment

Vaginal wall defects should be evaluated and treated by a urogynecologist or gynecologist experienced with POP. Conservative medical management includes pessaries and pelvic floor physical therapy. Numerous surgical procedures for POP include vaginal and abdominal approaches, with and without use of graft materials.

Unfortunately, there is little scientific evidence to determine the optimal approach to conservative versus surgical management. Two recent reviews show low quality evidence but suggest that pessaries or pelvic floor therapy may be valuable in the relief of symptoms of pelvic floor prolapse. At this time, the patient will need to decide her preferred approach with the advice of her physician.95 96

Vaginal changes after surgery

Prevalence

Vaginal surgery is common and may include repair of childbirth injury, surgery for repair of prolapse or incontinence, surgical treatment of polyps, pre-cancers or cancers, and hysterectomy for a variety of indications.

Etiology

Any vaginal surgical procedure can leave scarring.

Symptoms and clinical features

Most women with scarring as a result of surgery or childbirth recover without long-term symptoms. However, a subset of women will have persistent dyspareunia and/or vaginal/perineal pain. This is presumed to be related to the lack of flexibility of the scar tissue. Sadly there is little literature addressing this specific issue.

One review article97 showed that persistent perineal or vaginal pain was related to operative deliveries and to the amount of perineal trauma.

Techniques for hysterectomy and procedures for correction of prolapse and incontinence emphasize the preservation of a functional vagina with caliber and length adequate for sexual intercourse, but few data are available regarding what dimensions are necessary to avoid dyspareunia. Shortcomings in methodology have been problematic. Differences in types of hysterectomy cause varying changes in the post-operative vagina.

The type of closure of the vaginal cuff at the time of vaginal hysterectomy results in significant vaginal length differences: horizontal closure results in a 16% shorter vagina compared with vertical closure when length of the vagina is properly measured. There is no evidence on the effect of the shorter vagina on post-hysterectomy dyspareunia.98

There is a Cochrane Database meta-analysis showing morbidity-related advantages of the vaginal versus the abdominal approach. However, there was no significant difference in sexual dysfunction among vaginal, laparoscopic, or abdominal approaches.99

One other study of 104 women concluded that vaginal anatomy, measured by introital caliber, length, and vulvovaginal atrophy, does not correlate well with sexual function, particularly symptoms of dyspareunia.100

One other source of potential symptoms is the prolapsed fallopian tube, a rare complication of hysterectomy. The small portion of fallopian tube may be associated with dyspareunia, post-coital bleeding or persistent vaginal discharge.101

Differential Diagnosis

Scarring of the vagina may be related to other inflammatory vaginal conditions rather than post-surgical scarring.

Treatment

There are few data to direct care in this subset of women. Pelvic floor physical therapy and vaginal dilators may be of value. For significant scarring, surgical lysis can be considered. In the rare case of the prolapsed fallopian tube, surgical repair is generally chosen.

Erosive lichen planus of the vagina

Vaginal lichen planus may be seen with or without vulvar involvement, and can lead to telescoping, stricturing, or complete obliteration of the vagina. Please see detailed explanations elsewhere. (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium and Atlas of Vulvar Disorders.)

Fixed Drug Eruption

(Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium and Atlas of Vulvar Disorders)

Bullous erythema multiforme (Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)) (Annotation O: The vaginal epithelium and Atlas of Vulvar Disorders)

Overview

Fistulas may occur between the vagina and the bladder, the urethra, the colon, the rectum or the anus. Worldwide, the majority of fistulas relate to obstetrical trauma, largely in the developing world. In the US, the risk of fistula related to trauma is much lower.

The discussion below is divided into two parts: fistula from the vagina to the bowel and urogenital tract vaginal fistulas.

Rectovaginal, anovaginal and colovaginal fistulas

Introduction

A rectovaginal fistula (RVF) is an abnormal connection between the rectum and the vagina. If the connection between the bowel and the vagina is below the dentate line, the fistula is considered anovaginal and if the connection involves the bowel above the rectum, the fistula is considered colovaginal.

Etiology

- Injuries in childbirth. Worldwide, a conservative estimate suggests that 50-100K women develop fistulas related to childbirth per year. Other studies suggest that this number is underestimated.102 The fistulas related to childbirth are most often caused by long or obstructed labor and fetal demise is common; (more than 78% of women with fistulas did not have liveborn babies). Other identified risk factors include teenage birth, primiparity, maternal height less than 59 inches.103, 104

In the developed world, obstetric injuries from childbirth are rare. In Western counties, primiparity, midline episiotomies, increased birth weight, and the use of vaginal forceps are the risk factors associated with severe perineal lacerations.105

Often such lacerations are recognized and primarily repaired at the time of childbirth. However, subsequent dehiscence of the repaired laceration may occur, (4.6% of women in a previous study).106

- Crohn disease. The second most common cause of rectovaginal fistulas is the transmural inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract in Crohn disease.107 Although rectovaginal fistula is an uncommon complication of Crohn disease, one study showed a prevalence of 2.3% in women with Crohn’s.108. Additionally, the symptoms and exam may be obscured by the presence of fistula-in-ano, a connection between the anus and the perineal skin.109

- Vaginal, perineal, or ano-rectal surgery. Surgery in the lower pelvic region can lead to development of a fistula in rare cases. Rectovaginal fistula formation may occur after a difficult hysterectomy, such as one with extensive endometriosis. Several studies have found the risk of postoperative rectovaginal fistula after surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis to range from 2.9-10.6%. The size and location (cul-de-sac) of the resected lesions appear to be related to risk; a lesion size >4 cm is more risky.110 The incidence of RVF after operative treatment for low rectal cancer is reported to be 0.9% to 10%.111 Low and very low anterior proctosigmoidectomy, use of the double-staple technique, and combined resection of the uterus and/or partial vaginectomy during proctectomy are identified as risk factors for the development of RVF. Use of diverting ostomies in the setting of rectal cancer construction do not completely eliminate fistula risk, as RVF can occur in up to 11% of patients despite complete enteric diversion.112

- Pelvic cancer or radiation treatment. Malignancy of the rectum, cervix, vagina, uterus, or anal canal can lead to development of a rectovaginal fistula.113 Radiation therapy for cancers in these areas can also increase the risk of developing such fistulae.A fistula caused by radiation usually forms within two years following the treatment.

- Other causes. Less commonly, a rectovaginal fistula may be caused by infections in the anus or rectum, diverticulitis, or vaginal trauma. Abscesses arising from the crypts of Morgagni, Bartholin gland abscesses, and diverticulitis can cause intense inflammation that culminates in a fistulous tract with the vagina.114 Vaginal trauma can be induced by retained foreign bodies, such as pessaries, sexual objects.115 Traumatic vaginal intercourse, particularly in situations of rape or abuse, can result in RVF.116 117 Additionally, there are occasional reports of fistulas following the use of Nicorandil, a potassium-channel activator used for angina.118

Symptoms and clinical features

Women may present with complaints of gas, stool, or malodorous discharge per vagina. There may be rectal incontinence, dyspareunia, or perineal pain. Recurrent vaginal infection may be part of the history.

Diagnosis

History and physical examination are important triggers to diagnosis of rectovaginal fistulas.

- Besides medical, surgical, and obstetric history, questions regarding Crohn’s symptomatology are important. Any previous relevant surgical records should be obtained (if possible) and reviewed.

- Physical examination

- A complete pelvic examination with attention to the vaginal mucosa is essential. A fistula opening may not be visible but mucosal irregularity or thickening may be indicators. A colposcope allows magnification that may help with the diagnosis of a small fistula. Some will use a lacrimal duct probe to assist in identification of the fistula. Others describe the use of dyes. Two methods are discussed: using a small amount of methylene blue mixed into gel and then massaged into the anterior rectal wall or an enema with methylene blue in saline. Either approach may allow a small amount of dye to track through to the vagina and facilitate identification of the fistula opening.119

- Visual inspection of the perineum and perianal areas is needed, especially to look for signs suggestive of Crohn’s disease such as cutaneous fistula opening(s) or perianal fissures.

- A digital anorectal examination should also be performed. It may be helpful to use a topical anesthetic agent (commonly lidocaine gel) to facilitate the exam if needed. On rectovaginal exam, an area of fistula is often felt as an irregular mass arising from the rectovaginal septum.120

- Additions to the physical exam may include anoscopy or sigmoidoscopy to allow inspection for mucosal irregularities, stricture, or active proctitis.121

- Imaging

If a suspected fistula is not found during the physical exam, further work-up is necessary with specialized diagnostic imaging.

Ultrasound: Standard endoanal ultrasound can be used to locate internal openings and to define sphincter anatomy of anorectal fistula and RVF with 7% to 73% accuracy.122In women with obstetric injuries, performing an ultrasound is a routine part of the workup to also evaluate for a sphincter defect.

Computerized tomography: A study from 1990 found 60% accuracy in diagnosing RVF with early generation CT scanners; the accuracy of modern-day multislice scanners in localizing RVF is unknown.123

MRI: MRI is more accurate in diagnosing anorectal fistula and RVF than digital rectal examination, surgical examination, or ultrasound, approaching 100%. It is rapidly becoming the diagnostic imaging modality of choice.

If a fistula is not found during the physical exam, further work-up is necessary with specialized diagnostic imaging. Since MRI is more accurate in diagnosing anorectal fistula and RVF than surgical examination, ultrasound, and digital rectal examination,124 with accuracy approaching 100%,125 MRI is rapidly becoming the diagnostic modality of choice.

Treatment

The diagnostic challenges imposed by RVFs are only superseded by the difficulty of achieving successful long-term repair, and patients should be referred to a gynecologic or rectal surgeon with expertise in this area.

General principles for repair include the need for complete excision of the fistula tract along with a multilayer closure. Repair should not be attempted when active infection is present.

Obstetric and traumatic fistulas can usually be approached by the transanal or transperineal route, depending on the integrity of the sphincter. Reasonable outcomes can be expected in those patients who have normal rectal and vaginal tissue in close proximity to the defect.

Radiation-induced fistulas are problematic as the tissue is often weak or scarred. Surgical approaches vary with location of the fistula (low or high) but tissue interposition is recommended for these repairs.126

For women with fistulas due to inflammatory bowel disease, the best surgical results require that the underlying disease is in good control. Therefore, timing of the surgery is critical and should not be undertaken when Crohn’s disease is undertreated.127

Urogenital fistula

Introduction

Urogenital fistulas in women include any abnormal connection between the female genital tract and the urinary tract. The commonest of the urogenital fistulas is the vesicovaginal fistula (VFF) which will be the main focus of this discussion. Urethrovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas are less common.

In developing countries, the predominant cause of vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistula is prolonged, obstructed labor (97%). These fistulas are associated with marked pressure necrosis, edema, tissue sloughing, and cicatrization.128 There is some evidence that obstetric fistulas occur more commonly in women who have experienced female genital mutilation. 129 Others have not found that relationship.130

In contrast, countries with modern obstetric services have a low rate of childbirth related vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistulas although fistulas have been reported after operative delivery and after peripartum hysterectomy.

The majority of vesicovaginal fistulas in developed countries are a consequence of gynecological surgery. One major cause is hysterectomy. Although most authors quote an incidence rate of VVF after total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) of 0.5-2%, others suggest only a 0.05% incidence rate of injury to either the bladder or ureter. As a rough estimate, therefore, if injuries to the bladder and ureters occur in roughly 1% of major gynecologic procedures and approximately 75% are associated with hysterectomy, and if there are about 500,000 hysterectomies performed each year in the US, then about 5,000 women a year will experience an injury.

Additionally, incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy appears to be associated with an increased risk of vesticovaginal fistula. In a 2009 study of 1317 women with hysterectomy, 34 (2.6%) had an unplanned cystotomy identified. Of these 34 women, 11.7% developed a VVF. Identified risk factors for VVF included current smokers (OR 9.86). larger uteri and longer operative times.131

Hysterectomy is also one of the causes of iatrogenic urethral injuries with varying estimates of urethral trauma, ranging from 0.3% for experienced surgeons to as high as 14%. A variety of other factors affect the incidence of fistula formation after surgical ureteral trauma. Additional risk factors include endometriosis, obesity and malignancy.132

Other gynecology surgeries may also be associated with urethrovaginal fistula formation including urethral diverticulectomy, bladder neck suspension, anterior vaginal repair and vaginal hysterectomy.133 Synthetic mesh in stress urinary incontinence repair may be related to the development of urethrovaginal fistula, Additionally, vesicovaginal fistula may be a result of mesh use; it is possible for the mesh to be inadvertently placed into the bladder or the mesh may gradually erode into normal tissue causing a fistula.

There are reports of other uncommon surgical causes of fistula including, for example, ureterovaginal fistula after oocyte retrieval for IVF. A 2017 article reported one case and the authors’ literature review identified three other reported cases.134

Radiation therapy, which impairs the vascular supply to tissue within the radiation field, is also responsible for the development of fistulas in some cases.135

Urogenital fistulas are also reported as a result of sexual violence, particularly in areas of the world experiencing war.136

Symptoms and clinical features

Fistulas between the urinary tract and vagina are generally painless. A woman will usually present with either constant or intermittent incontinence. In particular, positional leakage can be a sign of vesicovaginal fistulas. With urethrovaginal fistulas, in contrast, the symptoms may vary with location of the fistula. If the connection is in the lower one third of the urethra, the woman may be continent and complain primarily of vaginal discharge of urine during or after urination. A lesion more proximally in the urethra will usually have similar symptoms to a VFF. Ureterovaginal fistulas also present with urinary incontinence but symptoms may also include fever or flank pain due to urinoma or obstructed kidney. With all of the types of urogenital fistula, vulvar irritation and recurrent infections are common associated problems.

Diagnosis

A detailed history is most helpful in raising a clinical suspicion for a fistula. A detailed inquiry about symptoms helps to identify urinary leakage from a fistula vs incontinence. The woman with a fistula is usually changing heavy pads frequently due to the volume of leakage. Additionally, urinary loss may be positional.

Any history of recent childbirth or gynecologic surgery should be determined. Other possible causes (cancer, radiation, trauma, sexual assault) should be ascertained.

As the diagnosis of vesicovaginal or urethrovesical fistula is primarily clinical, the examination is an essential next step. On vaginal examination, the fistula may appear as a small, red area of granulation tissue with no visible opening, or an actual hole may be seen. Additionally, more than one fistulous tract may be present, so the examination should be completed in detail even if a fistula has been identified. Urine may also be noted pooling in the vagina or dripping from a fistula. Magnification with a colposcope may help to identify a small lesion.

A small fistula, especially one near the top of the vagina, may be very difficult to identify. In this case, a dye test is an appropriate addition to the evaluation. Any dyed sterile fluid may be used (usually indigo carmine or methylene blue mixed into sterile saline) and instilled into the bladder through a catheter. A tampon or large cotton swab is placed into the vagina and then checked for dye. This method will usually not identify a ureterovaginal fistula, as that urine will likely still be clear.

If utererovaginal fistula is suspected, oral phenazopyridine may be given on the day of the test, turning the urine orange. When used in combination with the blue dye instilled to the bladder, this will help with identification of source or sources (as vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas may coexist).

Eventually, clinicians involved in fistula care will classify the fistula using one of the existing classification systems. Systems based on the anatomical appearance of the fistula do not necessarily predict the difficulty of repair, nor the post-operative prognosis.137

Treatment

Women with urogenital fistulas should be referred to experienced surgeons, usually a physician with either urology or urogynecology training. Additional information is often needed to assist surgical planning. Usually the patient will have a cystoscopy to assess the bladder and to attempt to identify the number and location of fisulous openings. Retrograde pyelography may be used to assess the ureters.

In practiced hands, skilled fistula surgeons routinely achieve a closure rate of over 80% for simple fistulas at the time of first operation.138 Accepted principles of closure include identification and protection of the ureters, wide mobilization of the fistula, and closure without tension.139 A successful closure of the fistula does not necessarily mean that the patient will be continent. Especially when the urethra is involved in the fistula, postoperative urethral incontinence can persist.140

References

- Kaufman, RH, Faro S. Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina, 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1994.

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A. Bo K, Brubaker LP, Delancey JO, Klarskov P et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 175:10-17

- Jannini, EA, d’Amati G, Lenzi Andrea. Histology and immunohistochemical studies of female genital tissue. In Women’s Sexual Function and dysfunction, Goldstein I, Meston CM, Davis SR, Traish AM, eds. London, Taylor & Francis, 2006. 122.

- How to remember the Internal Iliac Artery branches: the 2-4-4 rule/Anatomy; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8vRnioqVfU , accessed 21Feb2022.

- Baggish MS, Karram MM. Anatomy of the Vagina. In Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery, second edition, 2006. Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 336.

- Emmans JE, Woods ER, Allred EN, Grace E. Hymenal findings in adolescent women: impact of tampon used and consensual sexual activity. J Pediatr. 1994; 125:153.

- Olson RM, García-Moreno C. Virginity testing: a systematic review.Reprod Health.2017;14:61.

- The Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health: The Physical Signs of Child Sexual Abuse: an evidence-based review and guidance for best practice. 2015. p 54, p 57

- Mishori R, Ferdowsian H, Naimer K, Volpellier M, McHale T. The little tissue that couldn’t – dispelling myths about the hymen’s role in determining sexual history and assault. Reprod Health. 2019 Jun 3;16(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0731-8. PMID: 31159818; PMCID: PMC6547601

- Marhan M, Saleh A. The microscopic anatomy of the hymen. Anat Rec 1994; 149:313-18.

- Rogers DJ, Stark M. The hymen is not necessarily torn after sexual intercourse. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.)1998;317(7155):414

- Marhan M, Saleh A. The microscopic anatomy of the hymen. Anat Rec 1994; 149:313-18.

- Basaran M, et al. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen; case reports and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

- Lee KH et al. Imperforate hymen: A comprehensive systematic review. J Clin Med. 2019 Jan 7;8(1):56. doi: 10.3390/jem8010056.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 780, June 2019. Diagnosis and Management of Hymenal Variants.

- Neill SM, Lewis FM. Basics of vulval embryology, anatomy, and physiology. In: Ridley’s The Vulva, 3rd edition, Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009:12.

- Lee KH et al. Imperforate hymen: A comprehensive systematic review. J Clin Med. 2019 Jan 7;8(1):56. doi: 10.3390/jem8010056.

- Laufer MR. Congenital anomalies of the hymen and vagina. www.UpToDate.com, Aug 20, 2021

- Acar A, et al. Long-term results of an imperforate hymen procedure that leaves the hymen intact. J Obstet Gyn India. 2021 Apr;71(2):168-172

- Itana de Mattos Pinto e Passos and Renata Lopes Britto. Diagnosis and treatment of mullerian malformations. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 59 (2020)183-188.

- http://www.obgyn.wustl.edu/mm/files/VAGINAL%20AGENESIS.pdf

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Mullerian Agenesis: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Number 728 January 2018 (replaces CO 562, may 2013)

- Herlin MK et al. “Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome: a comprehensive update,” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases.2020, 15:214

- Burgis J. Obstructive Mullerian anomalies: case report, diagnosis, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:338–344

- Rock JA, Breech LL. Surgery for anomalies of the Müllerian ducts. In: Rock JA, Thompson JD, editors. Te Linde Operative Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 746–748.

- ACOG Committee Opinion. Management of Acute Obstructive Uterovaginal Anomalies. Number 779, June 2019.

- Rock JA, Jones HW, Jr.The double uterus associated with an obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:339–342.

- Zurawin RK, Dietrich JE, Heard MJ, Edwards CL. Didelphic uterus and obstructed hemivagina with renal agenesis: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:137–141.

- Boyraz G, et al. Herlyn-Werne-Wunderlich Syndrome; laparoscopic treatment of obstructing longitudinal vaginal septum in patients with hemoatocolpos – a different technique for virgin patients. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2020; 21:303-4.

- Laufer, MR. www.UpToDate.com. Congenital anomalies of the hymen and vagina. Aug 20, 2021

- Üstün Y, Üstün YE, Zeteroğlu Ş, Şahin G, Kamacı M. A Case of Transverse Vaginal Septum Diagnosed During Labor. Erciyes Medical Journal; 2005. 27 (3): 136–138.

- Ono A et al. Application of saline infusion sonocolpography in diagnosis and treatment of perforated transverse vaginal septum. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol 2019, Article ID 6738389. https;//doi.org/10.1155/2019/6738380

- Zizolfi B, et al. Perforated transverse vaginal septum in a virgin patient: a hymen-sparing hysteroscopic-ultrasound-guided approach. JMIG Jan 2021; 28(1):3-4

- Williams CE et al. Transverse vaginal septae: management and long-term outcomes. B JOG; 2014 Dec;121(13):1653-8

- Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Pokanzer DC. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. NEJM. 1971; 284 (15): 878

- Hatch E and Karam A. Outcome and follow-up of diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposed individuals. www.UpToDate.com, accessed December 11, 2021

- Kondi-Pafiti A et al. Vaginal cysts: a common pathologic entity revisited. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology. Jan 2008; 35(1): 41-44

- Adrich ER and Pauls RN. Benign cysts of the vulva and vagina: a comprehensive review for the gynecologic surgeon. OBGYN Survey. 2021;76(2):101-7.

- Adrich ER and Pauls RN. Benign cysts of the vulva and vagina: a comprehensive review for the gynecologic surgeon. OBGYN Survey 2021;76(2):101-7

- Heller DS. Vaginal cysts: a pathology review. J Lower Genital Tract Disease 2012; 16(2);140-144

- Rivlen ME et al. Hemorrhage in a vaginal cyst. World J of Clin Cases 2013; 1(1): 34-36

- Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A. Congenital urogenital anomalies that are associated with the persistence of Gartner’s duct: a review. AJOG. 2006;195(2): 254-259

- Heller D. Vaginal cysts: a pathologic review. J Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2012; 16(2): 140-144

- Hoogendam JP and Smink M. Gartner’s Duct Cyst. NEJM. 2017; 376(14):e27

- Hagspiel KD. Giant Gartner duct cyst: magnetic resonance imaging findings. Abdom Imaging 1995; 20(6):566-568.

- Troiano RN, McCarthy SM. Mullerian duct anomalies: imaging and clinical issues. Radiology 2004; 233(1):19-34

- Adrich ER and Pauls RN. Benign cysts of the vulva and vagina: a comprehensive review for the gynecologic surgeon. OBGYN Survey. 2021;76(2):101-7

- Rovner ES. Urethral Diverticula. In: Raz S, Rodriguez L, ed. Female Urology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2008. 815-34

- Quiroz LH and Gutman RE. Urethral diverticulum in women. www.UpToDate.com Accessed 10/30/21

- Leach, GE, Bavendam, TG. Female urethral diverticula. Urology 1987; 30:407

- Athanasopoulos, A, McGuire, EJ. Urethral diverticulum: a new complication associated with tension-free vaginal tape. Urol Int 2008; 81:480.

- Clemens, JQ, Bushman, W. Urethral diverticulum following transurethral collagen injection. J Urol 2001; 166:626.

- Pradhan M, Ranjan P, Kapoor R. Female Urethral Diverticulum Presenting with Acute Urinary Retention: Reporting the Largest Diverticulum with Review of the Literature. Indian J Urol 2012; 28(2):216-18.

- Eilber KS, Raz S. Benign cystic lesions of the vagina. J Urol 2003(170):717-722.

- Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. J Urol. 2000; 164(2):428-433

- Aspera, AM, Rackley, RR, Vasavada, SP. Contemporary evaluation and management of the female urethral diverticulum. Urol Clin North Am. 2002; 29:617.

- Lee, JW, Fynes, MM. Female urethral diverticula. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005; 19:875.

- Rovner ES. Urethral Diverticula. In: Raz S, Rodriguez L, ed. Female Urology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2008. 815-34.

- Schenken RS. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis of endometriosis. www.UpToDate.com, 2010.

- Kaufman, RH, Faro S. Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina, 4th ed. 1994.

- Marinis, A, Vassiliou, J, Kannas, D, et al. Endometriosis mimicking soft tissue tumors: diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006; 27:168.

- Alhatem A, Heller DS. Fibroepithelial (stromal) polyp. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/vaginafibroepithelial.html . Accessed 12/12/21

- Nucci MR, Fletcher CDM. Vulvovaginal soft tissue tumours: update and review. Histopathology. 2000; 36:97-108.

- Nucci MR, Fletcher CD. Vulvovaginal soft tissue tumours: update and review. Histopathology. 2000; 36:97-108.

- Fauth C et al. Clinicopathologic determinants of vaginal and premalignant-malignant cervico-vaginal polyps of the lower female genital tract. J of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2011; 15 (3): 210-218

- Nucci MR, Fletcher CDM. Fibroepithelial stromal polyps of vulvovaginal tissue. From the banal to the bizarre. Pathol. Case Reviews. 1998; 3; 151–157.

- Maenpaa J, Soderstrom KO, Salmi T, Ekblad U. Large atypical polyps of the vagina during pregnancy with concomitant human papilloma virus infection. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1988;27:65-69.

- O’Quinn AG, Edwards CL, Gallager HS. Pseudosarcoma botryoides of the vagina in pregnancy. Gynecol.Oncol 1982;13;237-241.

- Nucci M, Young R, Fletcher C. Cellular pseudosarcomatous fibroepithelial stromal polyps of the lower female genital tract: an under-recognized lesion often misdiagnosed as sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000 Feb;24(2):231-240

- Alhatem A, Heller DS. Fibroepithelial (stromal) polyp. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/vaginafibroepithelial.html . Accessed 12/12/21

- Nucci M, Young R, Fletcher C. Cellular pseudosarcomatous fibroepithelial stromal polyps of the lower female genital tract: an under-recognized lesion often misdiagnosed as sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000 Feb;24(2):231-240

- Sherer DM et al. Sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings of an isolated vaginal leiomyoma. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26:1453-1456.

- Dane C, Rustemoglu, Kiray M, et al. Vaginal leiomyoma in pregnancy presenting as a prolapsed vaginal mass. Hong Kong Med J. 2012; 18(6):533-35

- Kaufman, RH, Faro S. Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina, 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1994.

- Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Vaginal topography does not correlate well with visceral position in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1997; 8(6):336-9

- Rogers RG, Fashokun TB. Pelvic organ prolapse in women: epidemiology, risk factors, clinical manifestations and management. www.UpToDate.com, last updated Jul 5, 2021, accessed Dec 15, 2021

- Olsen, AL, Smith, VJ, Bergstrom, JO, Colling, JC, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 89:501

- Jones KA, Shepherd JP, Oliphant SS, et al. Trends in inpatient prolapse procedures in the United States, 1979-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202(5):501.

- Rogers RG, Rashokun TB. An overview of the epidemiology, risk factors, clinical manifestations, and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. In: UpToDate, Bason DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013.

- Graves EJ; Gillum BS. Detailed diagnoses and procedures, National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1995.Vital Health Stat 13. 1997 Nov;(130):1-146.

- Rogers RG, Fashokun MD.. An overview of the epidemiology, risk factore, clinical manifestations, and management of pelvic organ prolapse. In:www.UpToDate.com, Basow DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham Mass; 2013.

- Swift, SE, Tate, SB, Nicholas, J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: What is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189:372.

- Gutman RE, Ford DE, Quiroz LH, et al. Is there a pelvic organ prolapse threshold that predicts pelvic floor symptoms? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 199(6):683.

- Novi JM, Jeronis S, Morgan MA, Arya LA. Sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse. J Urol 2005; 173(5):1669-72.

- Heit M, Rosenquist C, Culligan P, et al. Predicting treatment choice for patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 10(6):1279-84.

- Swift SE, Tate SB, Micholas J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 189(2):372-7.

- Marinkovic SP, Stanton SL. Incontinence and voiding difficulties associated with prolapse. J Urol 2004; 171(3):102-8.

- Burrows LJ, Meyn LA, Walters MD, Weber AM. Pelvic symptoms in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104(5 Pt 1):982-8.

- Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet 2007; 369(9566):1027-38.

- Mouritsen L, Larsen JP. Symptoms, bother and POPQ in women referred with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J pelvic Floor dysfunct 2003; 14(2):122-7.

- Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet 2007; 369(9566):1027-38.

- Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet 2007; 369(9566):1027-38.

- Bump RC, Mattiasson A, BO K, et al. The Standardization of Terminology of Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1996; 175(1):10-17

- Lentz GM. Anatomic defects of the abdominal wall and pelvic floor. In: Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, (Eds). Comprehensive Gynecolgy. Philadelphia, Mosby Elsevier, 2007, 510

- Vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse of stress urinary incontinence: a health technology assessment. Ontario Health Technology Assessment 2021; 21(3):1-155

- Bugge E et al. Pessaries for managing pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020; 11; 1-55. Art. No CD004010.

- Komatsu R, Ando K, Flood PD. Factors associated with pain after childbirth: a narrative review. B J Anesthesia 2020; 124(3): e117-e130.

- Vassallo BJ, Culpepper C, Segal JL, Moen MD, Noone MB. A randomized trial comparing methods of vaginal cuff closure at vaginal hysterectomy and the effect on vaginal length. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 195(6):1805-1808.

- Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr L, Garry R. Methods of hysterectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2005;330:1478