Annotation K: Vulvar pain and vulvodynia

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationFor more on vulvodynia, go to the National Vulvodynia Association:www.nva.org.

To hear the voices of women with vulvovaginal pain, go to www.tightlipped.org.

Be sure to use the back arrow to return to this website.

This material is also found in Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia with additional content in two other pain-related sections: Vaginismus and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Vulvovaginal Pain and Sexuality.

Since the 1980’s, important advances in research on vulvodynia have fostered better understanding of the intricacies of vulvovaginal anatomy and physiology and of pain itself. There has been a gradual shift away from the hope of a single cause and a single treatment for vulvodynia and an increased understanding that the condition is multifaceted, requiring an approach that considers the whole body, in all of its complexity.

In the early days of patient evaluation, we were armed only with visual inspection, a Q-tip, and the patient’s reported pain scale, with very limited knowledge about the vulva, the vestibule, the vagina, and the neurology of pain perception. Today, more health care providers are aware of the global impact of vulvovaginal pain on women’s lives, and researchers are making heroic efforts not only to understand possible causes, but also to evaluate the treatments that have been used up till now and to seek out new treatments that are based on solid evidence. Many topical and oral treatment methods previously thought to be effective for vulvodynia (at least to some extent), are now shown not to have scientific support for efficacy. Currently, studies are being assessed more stringently for validity; randomized controlled trials are encouraged, and consensus on core outcome domains for vulvodynia, that will improve the ability to perform meta analyses, is being sought.1 2

It is no small accomplishment that after forty years of sometimes conflicting research, there is strong evidence that the vulva and vagina have unique inflammatory and immunological properties. Also, specialized immunological blockers (lipids produced endogenously within the body), hold promise as a vestibulodynia treatment by resolving inflammation without impairing the host defense system.3 In August 2023 Harlow et al released a study strongly supporting the auto-immune hypothesis. They identified all women born in Sweden between 1973 and 1996 diagnosed with localized provoked vulvodynia (LPV) or vaginismus, matching each case to two women born in the same year with no vulvar pain and no ICD vulvar pain codes. As a proxy for immune dysfunction, they used Swedish Registry data to amass single organ or multi organ immunodeficiences, allergy and atopy, and malignancies involving immune cells. Women with vulvodynia, vaginismus, or both were more likely to experience immune deficiencies, single organ or multi -organ immune conditions and allergy/atopy conditions compared to controls. With increasing numbers of unique immune related conditions, risk was greater. The research suggests that women with vulvodynia may have a more compromised immune system either at birth or at points across the life course than women with no vulvar pain history. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that chronic inflammation launches the hyperinnervation that causes the debilitating pain in women with vulvodynia.4

The following section, Pain Basics, provides a simple groundwork for better understanding of how pain works in general and also in the vulva and vagina. (We have isolated the sections on Pain Basics and Pathophysiology, requiring you to open them to read them, because of their complexity, understanding that you may want to proceed directly to Diagnosis and Treatment).

Introduction

It is gratifying to lessen pain for one who suffers, and equally disturbing to be unable to help. Pain management of vulvovaginal disorders often entails, for clinicians, a comprehension beyond the level provided in their education or professional experience. Indeed, even clinicians highly experienced in diagnosing and treating patients with vulvovaginal complaints are baffled by the problem of persistent pain. Fortunately, better comprehension of the neurobiology of pain has evolved. There have been advances in functional brain imaging, further development of animal models, and the switch from a biomedical model in which nociception and pain were considered practically synonymous, to a biopsychosocial model where pain is seen as a response from the brain, and nociception can play a highly variable encoding and transmission role.

Nociception

Nociceptors are a group of sensory neurons that function as the primary unit of pain messaging. Located on A-delta and C nerve endings in skin, muscle, bone and viscera, they are endowed with receptors and ion channels that promote the detection of potentially noxious stimuli. They mediate the conversion of a sensory stimulus into an electrical signal that the brain can interpret (timing, intensity, modality, location, threshold).5 This high threshold pain signal causes action only by exposure to toxic molecules and inflammatory mediators or something intensely hot, cold, or sharp. The impulse advances to the dorsal root ganglion, then traverses to the contralateral side of the spinal cord to activate neurons in the anterior horn to produce a reflex; or the signal ascends with its message to the parabrachial area in the midbrain, then on to higher cortical centers, including the hypothalamus, the amygdala, and parts of the thalamus. The sensation of pain appears when nociceptive messages are integrated into brain networks that meld thoughts, feelings, memories, and other sensations: a cascade of molecular, cellular, electrical, and neuroimmune events. Therefore, nociception (and any other pain) becomes real only with the brain’s involvement as well as conscious awareness. Treatment must be directed to both the noxious stimuli and the brain.6

An important recent advance is recognition that the experience of pain is distinct from nociception. Nociception is the neural process of encoding noxious stimuli. Nociception is a form of messaging service which describes afferent neural activity transmission of sensory information about stimuli that have the potential to cause tissue damage. Pain is actually a complex sensory state that reflects the integration of many sensory signals with elaborate brain processing.7 In the long run, pain perception is a process mediated by the cerebral cortex. From the early perception of sensory stimuli, the dynamic spinal ascent of this information results in a nociceptive message that can be acted on, ignored, or even distorted by brain circuits.8

Over time, without further tissue injury, this state of heightened sensitivity returns to the normal baseline, where high-intensity stimuli are again required to promote nociceptive pain; the phenomenon is long lasting but not permanent.9

There is also the possibility that neurons are not alone in the development of pathological pain, (although it is still hotly debated whether vulvovaginal pain is pathologic pain). Numerous immunological pathways mediated by glia (non-neuronal cells considered part of the neural communicating system), as well as immune cells, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines modify neuronal communication leading to pathological pain.10 A full discussion of neural pathways is beyond the scope of this website. However, current pain therapeutics neglect the actions of these non-neuronal contributors. Therefore, development of interventions designed to target neuroimmune communication may improve patient outcomes.11

Peripheral and central sensitization

An additional important phenomenon that further escalates the protective function of the nociceptive system is the peripheral and central sensitization that occurs after repeated or particularly intense noxious stimuli.12 This sensitization is the result of use-dependent synaptic plasticity triggered in the central nervous system (CNS) by the nociceptor input. It represents the first example of central sensitization, discovered years ago.13

Neuronal plasticity consists of peripheral sensitization in primary sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia14 and central sensitization of pain-processing neurons in the spinal cord and brain.15 Nociceptors are activated or sensitized by inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin, prostaglandins, nerve growth factor, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin 1β, and other proinflammatory chemokines16 that directly bind and stimulate a mosaic of peripheral receptors. The threshold for activation of the pain message lowers, yielding hypersensitivity and hyperexcitability of nociceptor neurons (peripheral sensitization) through modulation of various ion channels.17

If the peripheral nerve is damaged and the noxious messages persist, the threshold for activation of the pain message lowers, and responses to subsequent inputs are amplified, yielding increased firing of the nociceptive fibers and increased sensitivity of the A fibers.18 This is peripheral sensitization. When it occurs, allodynia in the vestibule arises from hypersensitivity to stimuli that are not normally painful. Hyperalgesia (increased response to stimuli that are not normally painful) heightens the pain.19

Similar to peripheral sensitization, central sensitization results in neural signaling within the central nervous system.20 Subthreshold synaptic signals to nociceptive neurons are recruited, augmenting action potential output: a state of facilitation, potentiation, augmentation, or amplification which is the fundamental contribution of the central nervous system in the generation of pain hypersensitivity. Because central sensitization arises from alteration of neuronal properties in the central nervous system, the pain is no longer coupled, as acute nociceptive pain is, to the presence, intensity, or duration of noxious peripheral stimuli. Instead, central sensitization yields pain hypersensitivity by changing the sensory response to normal experiential inputs, (including those that usually evoke innocuous sensations), leading to allodynia.21 Intense and prolonged painful stimuli cause an exaggerated response of excitatory and inflammatory neuropeptides, and an increased number of synapses in neurons. As was just stated, this produces neuronal excitability to noxious stimuli and innocuous (light touch) stimuli. It creates pain hypersensitivity in non-inflamed tissue by changing the sensory response elicited by normal inputs even when no peripheral pathology may be present. This sensitized state involves both spinal cord mechanisms, at the level of the dorsal horn and below, descending and supraspinal mechanisms that involve the augmented response of a network of higher brain centers. Pain is not then simply a reflection of peripheral inputs or pathology but is also a dynamic reflection of central neuronal plasticity. The plasticity profoundly alters sensitivity to an extent that it is a major contributor to many clinical pain syndromes and represents a major target for therapeutic intervention.

Descending modulation: inhibition of nociception

Central sensitization involves both spinal cord mechanisms, at the level of the dorsal horn and below, and supraspinal mechanisms that involve the augmented response of a network of higher brain centers. The sensory pain encounter can also be modified by descending modulation. The same neurons promoting top down facilitation of nociception may change to inhibition of nociception in the brain centers and spinal cord. Pain experience can be augmented or lessened depending on anticipation, attention or distraction, emotional state, mood, anxiety, coping style, outlook, tendency to catastrophize, learning, and memory. 22 The parabrachial pathway of the midbrain also projects to other centers involved in the descending control of pain, including the rostral-ventral, medulla, and the periaqueductal gray area. These descending control mechanisms are responsible for a reduction in the sensation of pain and the inhibition of its spread upon the perception of pain.23 Central sensitization may also include conditions like increased central responsiveness due to dysfunction of endogenous pain control systems (descending modulation), regardless of whether there is functional change of peripheral neurons.24

“With greater understanding of peripheral and central sensitization,and the role of neural plasticity we celebrate our progress, although clearly, more is still waiting to be learned.”25

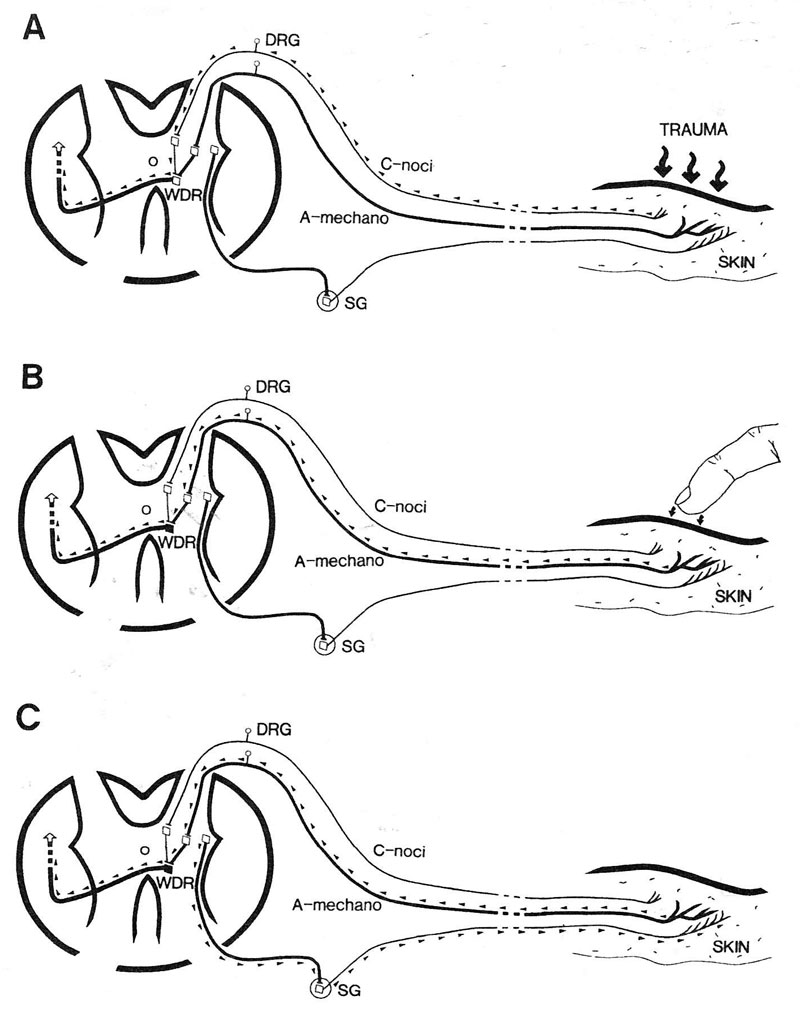

Figures K1 A-C show a schematic diagram of a physiological model for peripheral nerve sensitization.26

Figure K1-A shows the immediate response of nociceptive fibers to cutaneous trauma. Action potentials propagate through the dorsal root ganglion to the spinal cord to activate and sensitize wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons with axons ascending to higher centers.

Figure K1-B shows the now sensitized WDR responding to activity from touch of the large diameter A-mechanoreceptors activated by light touch.

Figure K1-C shows that with activity from central sensitization, the neurons can discharge spontaneously when there is noxious stimulus in the periphery.

Classification of pain

Without a better understanding of vulvodynia, classification of pain type is not yet clear. Over the years, several different classifications of the pain of vulvodynia have been promoted, but no one system has been accepted universally.27 Categorization, as imperfect as it is however, can still help to conceptualize different aspects of pain:

- Nociceptive Pain results from the activation of a subset of sensory neurons termed nociceptors, previously thought of as a “detect and protect mechanism,” now considered more dynamic. An important recent advance is recognition that the experience of pain is distinct from nociception. Nociception is the neural process of encoding noxious stimuli, a form of messaging which describes afferent neural activity transmission of sensory information about stimuli that have the potential to cause tissue damage. Pain is actually a complex sensory state that reflects the integration of many sensory signals with elaborate brain processing.28

- Inflammatory pain (IP) occurs after unavoidable tissue damage, e.g with joint inflammation, surgical wounds, or severe, extensive injury; sensory sensitivity is heightened to assist healing by discouraging movement or physical contact; the “dolor” reduces risk of further damage. This pain occurs as the immune system is activated by the initial tissue damage. It is low threshold pain, considered adaptive, but it mandates treatment of the ongoing inflammation.29

- Pathological pain: a) Neuropathic pain (NP) appears after development of a neural lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. It is not protective but maladaptive, representing a disease state of the nervous system. This is not a warning to prevent physical injury or disease. It IS the disease—the result of neural mechanisms gone awry.30 Vulvodynia has been inaccurately called neuropathic pain, that is, disease of the somatosensory nervous system, but no neural lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous has been demonstrated. Whether nerve injury or infection are included in somatosensory lesions needs clarification. b) Dysfunctional pain, that is, nociplastic pain,31 encompassing functional somatic syndromes (FSS), includes, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, painful bladder syndrome, tension headaches, temporomandibular joint disease, and other syndromes of substantial pain, all without known noxious stimulus, and minimal or no peripheral inflammatory pathology.32 Since FSS include the entire group of comorbidities associated with vulvodynia, the pain of vulvodynia has also been included in the FSS or dysfunctional pain category by many experts.33 34 35 36 The concept of vulvodynia and FSS as dysfunctional pain continues to be debated.

Multiple professional societies try to contribute clarity to the process of diagnosis by creating terminology and classification systems, but this process can culminate in confusion as well as diagnosis codes. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published in 2013, is the primary authority for psychiatric diagnoses.37 The new classification “genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder” in the DSM-538 is located in this compendium of psychiatric illnesses under the category of sexual dysfunctions and includes the previous terms “dyspareunia” and “vaginismus.” Vulvodynia is ostensibly there as a subset of dyspareunia, though not specifically so. Viera-Baptista, et al and others39 40 warn that there is room for misinterpretation and misunderstanding in this DSM-5 designation, saying, vulvodynia “…is not to be considered a sexual dysfunction, but rather a chronic dysfunctional pain disorder. Dysfunctional pain is defined as a disease state of the nervous system, which arises by its abnormal function, in the absence of neural structural damage.” They also point out that, “vaginismus” and “dyspareunia,” located together, can lead to confusion about the conditions and their therapeutic approaches.41 Bergeron, et al consider that this new categorization actually broadens the scope of definition for vulvodynia, as it allows for vulvar pain, deep pain, and pelvic pain on penetration.42 They mention other pain classification systems that include vulvodynia. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) lists vulvodynia under “chronic primary visceral pain” within subcategories of pelvic pain.43 The 11th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems has included vulvodynia within the chronic pain syndromes for the first time.44

In this website, we have addressed pelvic floor dysfunction/vaginismus separately (https://vulvovaginaldisorders.org/pelvic-floor-dysfunction/) because although there are overlaps pertaining to pelvic floor muscle tone and the psychological effects of pain or fear of pain in both vulvodynia and vaginismus, the focus of therapeutic modalities may be different.

2015 ISSVD Consensus on Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain

The accepted, most useful, nomenclature in categorizing vulvar pain/vulvodynia at this time is found in the 2015 consensus statement of a consortium of professional organizations on terminology that clarifies what is understood about vulvar pain from identifiable (“known”) causes and pain with unknown cause but with potential associated factors: vulvodynia.45 Click here to see the original terminology document

The addition of “potential associated factors” to the terminology initiated the deeper study of vulvodynia as a multifactorial process. We have adapted the definitions or rearranged tables below for the purpose of this document, but have stayed true to the intent of the original consensus statement.

In the 2015 consensus statement, three pain categories were identified, along with “descriptors” related to characteristics of the pain.

- Vulvar pain related to a recognizable disorder (such as infection, dermatosis, estrogen deficiency, or other identifiable condition) (see Table K1 below),

OR

2. Vulvodynia: vulvar pain of at least 3 months duration in the absence of clinically identifiable disease, (with possible associated biomedical and psychosocial factors),

OR

3. Pain with both a specific disorder (e.g. lichen sclerosus) and vulvodynia.

Although originally allocated to the diagnosis of vulvodynia alone, the following descriptors apply to both known conditions causing vulvar pain (especially those causing dyspareunia) AND to vulvodynia. 46 47

- Localized (e.g. vestibulodynia, clitorodynia, or pain in another limited location) or generalized or mixed (localized and generalized)

- Provoked (e.g. insertional, or with contact) or spontaneous (without touch), or mixed (provoked and spontaneous)

- Primary: with first tampon use or attempt at sexual penetration or secondary: developing after a period of comfortable penetration48 49

- Temporally intermittent, persistent, constant, waxing and waning, immediate, delayed, etc.

Associated biomedical and psychosocial factors that may contribute to vulvodynia have been identified (see following list) and form the basis of research into causes.50 These factors may also be seen as determining recognizable subgroups that may benefit from different treatment modalities.51 52 The word “subgroups” must be interpreted within contexts, though, as different specialists (such as neurologists and physical therapists, as well as researchers looking at the physiology of vulvodynia) may use the term uniquely within their own specialty. The “factors” will be addressed under Pathophysiology below. In some cases, there is overlap of “known” and “unknown” causes and, with future study, more factors will move into the “known” column.

- Inflammation

- Immunology

- Genetics

- Hormonal influences (e.g. endogenous or exogenous)

- Musculoskeletal (e.g. pelvic muscle weakness or overactivity, myofascial, biomechanical)

- Neurologic mechanisms

- Central (spine, brain)

- Peripheral

- Neuroproliferative

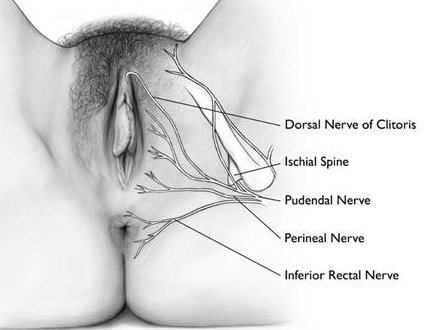

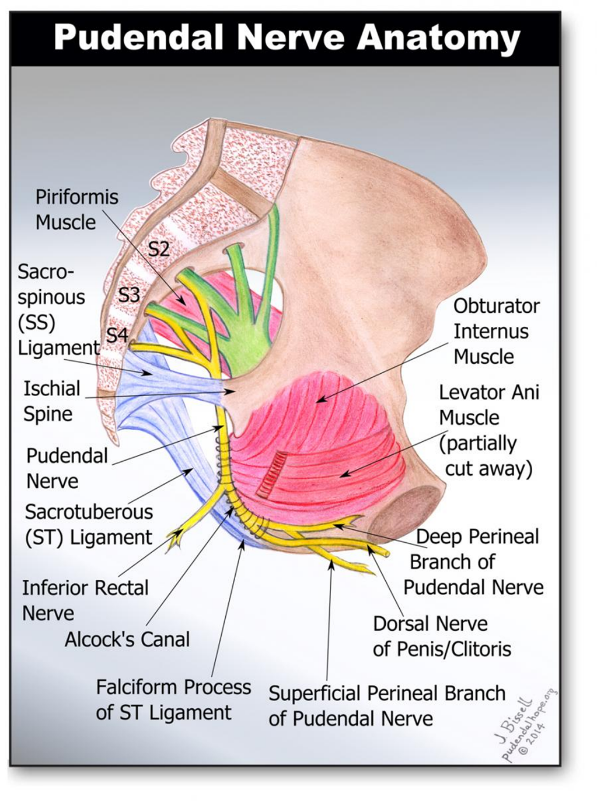

- Pudendal nerve related

- Comorbidities and other pain syndromes (e.g. painful bladder syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular disorder)

- Psychosocial factors (e.g. stress, mood, interpersonal, coping, role, sexual function)

- Structural defects (e.g., perineal descent)

Localized provoked vulvodynia/vestibulodynia, (pain with light touch in the vestibule, present for at least three months, without identifiable cause, abbreviated here as LPV/PVD because both “LPV” and “PVD” are used in different studies) is the focus of most researchers because it is more common than other types of vulvar pain in premenopausal women,53 is strongly associated with female sexuality, and is therefore highly impactful for patients and their partners. Women and girls of all ages can be affected but most are in younger age groups, a high proportion under 25 years.54 55 Studies of childhood vulvodynia are few; in many cases, persistent pain is found to have an underlying cause. Despite the pain, the majority of women continue to have sex.56 Dyspareunia in postmenopausal (and lactating) women is known to be related to vulvovaginal atrophy, but more and more studies remind us that pain that persists in menopausal women using vaginal estrogen may be related to vestibulodynia.57

Generalized vulvodynia (GVD), more common in peri- and postmenopausal women,58 has not received the same attention as LPV/PVD, and there are limited specific references in evidence based literature.59 60 Localized or generalized vulvodynia may be related to varying degrees of compression of different segments of the pudendal nerve. Persistent pain after vestibulectomy may represent a pudendal nerve neuroma61 and nerve entrapment is thought to be a source of persistent genital arousal syndrome (PGAD).62 Click here for Consensus Nomenclature and Process of Care for the Management of Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder/Genito-Pelvic Dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD)

Pudendal neuralgia (PN) is an underestimated yet important source of pain to consider during a workup. Because it is difficult to diagnose pudendal nerve-related disorders with any certainty in most women’s health practices (i.e. there is nothing visible to identify them), we have included these conditions under the category of vulvodynia, (whereas ISSVD, et al. in the 2015 consensus terminology, include them under “known causes of pain”).

Vulvodynia can disappear spontaneously, but frequently recurs. Of 239 women with vulvodynia (treatment status not indicated) in a two-year prospective study, 10% had persistent pain, and 90% experienced remission. However, half of the remission cases relapsed, often quickly. A history of longstanding pain with increased severity was more likely to persist.63

Vulvodynia burdens the health care system. Women with vulvodynia seek help from multiple health care providers, including family doctors, gynecologists, dermatologists, urologists, and alternative health practitioners. These clinicians may not be familiar with the signs and symptoms of vulvodynia, resulting in multiple visits, misdiagnoses, and delays in appropriate diagnosis and treatment. The burden not only impacts the affected woman, her family, and/or her intimate partner, but also society in general. It has been estimated that the annual economic burden of vulvodynia in the US is $31-72 billion.64 This cost includes direct health care costs, indirect health care costs (e.g., transportation to hospital), and indirect societal costs (e.g., sick leave).

Findings from available epidemiologic studies, well described in Bergeron et al’s excellent article,65 indicate that vulvodynia is a common gynecological pain syndrome, prevalent in women of all ages. To date, no global epidemiological studies have been done. In a preliminary survey, (prior to the first epidemiological study in the US), researchers showed that women from the general population were willing to provide sensitive information on lower genital tract discomfort—a first step toward bringing notice to this understudied disorder. In addition, the data supported the theory that vulvar trauma in early life may influence or serve as a marker for risk of subsequent chronic vulvar disorders.66 Subsequently, the main study of >5,000 women in Boston neighborhoods found that as many as 16% of these women experienced vulvodynia. By restricting the population to women with no lifetime histories of pelvic disorders such as endometriosis or leiomyomata, the authors conservatively estimated that at least 9% of women will experience a condition likely to meet vulvodynia criteria at some point. They continued: “If our lifetime cumulative incidence estimate is anywhere near the true prevalence, approximately 14 million US women may experience this problem in their lifetimes.”67 Another US study replicated Harlow and Stewart’s work, demonstrating that 8% of women 18-40 years old gave a history of vulvar burning or pain upon contact continuing over 3 months, limiting or preventing vaginal penetration/intercourse. The study indicated that women of Hispanic origin were more likely to develop vulvar pain symptoms than non-Hispanic white women.68 Arnold and Bachmann, et al. found a lifetime prevalence of 9.9%; 45% of these women revealed an adverse effect on their sexual experiences.69 A lifetime prevalence of 13% was shown in a recent, large study from Spain,70 and a Portuguese survey indicated a lifetime prevalence of 16%.71 However, another large study of women from Nepal, evaluated at a dermatology outpatient clinic, indicated that only 1% had vulvodynia.72 It is possible that this low number reflects patient embarrassment and reluctance to report vulvar pain or dyspareunia, or provider lack of education or disregard of the condition and discomfort with management of these women. All of these factors have resulted in widespread ignorance about this devastating condition.73

Although women of all ages may experience vulvodynia, prevalence may vary with age groups. In the USA, the National Health and Social Life Survey revealed that 21% of sexually active women aged 18-29 years experienced pain during sexual intercourse during the prior 12 months. Percentages were lower in older women: 13% of women aged 30-49 years and 8% in the 50-59 years group.74 Of 1,425 sexually active Canadian women aged 13-19 years, 20% identified pain at the vaginal opening during intercourse for over six months.75 6,777 sexually active British women aged 16-74 years, participating in a probability sample survey, showed that the prevalence of pain with sexual intercourse was highest (9.5%) in those aged 16-24 years and in those aged 55-64 years (10.4%). 76 The high prevalence in postmenopausal women in this study, compared with other studies, may arise from the inclusion of only sexually active women in the British sample. In addition, whether or not treatment for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy was being used was not addressed.77

Vulvodynia is a diagnosis of exclusion. Known disorders, that is, conditions which can be identified clearly, (although often unfamiliar to many clinicians), need to be ruled out before the diagnosis of vulvodynia can be made.78 The following table demonstrates specific disorders which can be a source of recognizable vulvar pain.

Table K-2 Possible causes of vulvovaginal pain from specific disorders (and associated links to information in this website)

| Candida vaginitis (P) | Cellulitis (Atlas of vulvar disorders) |

| Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) (P) | Systemic diseases, e.g., Crohn (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) Sjögren (O) |

| STIs: trichomonas (P), herpes (Herpes simplex), chancroid (Atlas of vulvar disorders ) | Fistulas (N) |

| Hypo Estrogenization (genitourinary syndrome of menopause or lactational atrophy), inadequate lubrication (P) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Drug reaction (O) |

| Irritants and allergens, irritant or contact dermatitis (J)(H) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Congenital anomalies (imperforate hymen (N), vaginal septum) (N) |

| Dermatoses with erosions, fissures (e.g. lichen sclerosus, lichen planus) (H) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Squamous cell carcinoma, other cancer and treatment for cancer, (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders), Extramammary Paget Disease (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

| Dermatoses with ulcers (e.g. aphthous ulcers, pemphigus, pemphigoid) (H) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Semen allergy (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

| Plasma cell vulvitis (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Pudendal nerve compression or neuroma (K) |

| Trauma (obstetrical, female genital cutting) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) | Iatrogenic (post-op, post radiation or chemotherapy) (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

| Psychosexual issues leading to poor sexual arousal, vaginismus (D) (Vulvovaginal pain and sexuality)

Vulvovaginal neoplasia (Atlas of Vulvar Disorders) |

A single cause for vulvodynia has not been identified. There is general acceptance that vulvodynia etiology is multifactorial: a varying group of influences or disorders causing similar symptoms. Studies related to the experience of pain of unknown origin also remind us that body and mind can not be separated; each biopsychosocial factor influences the others. In addition, vulvodynia research over the past two decades has revealed numerous associated abnormalities in body organs and tissues and compensatory pain mechanisms and pain pathways. Evolving information on how the brain works is just beginning to reveal new ways of understanding pain perception and processing in both vulvodynia patients and healthy controls.79 80 81

Data from these ongoing studies support the shift away from the paradigm of one cause for vulvodynia. In fact, the assumption that a blanket diagnosis of vulvodynia will direct one specific treatment is erroneous.82 It has become clear that treatment must be individualized, multimodal, and include the skills of a team of specialists. More researchers are looking carefully at the “associated factors” to direct this personalized care, as understanding them may lead to identification of vulvodynia subtypes that require different treatment modalities. (see Pathophysiology below).

Etiology of pudendal nerve-related pain (PN) is not always clear, but it is believed to result from nerve injury caused by stretching (childbirth, chronic constipation, perineal descent), entrapment, or compression (trauma, fracture of the pelvis, entrapment of the nerve between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments or within Alcock’s canal, related to pelvic surgery, tumors, infection, chemoradiation, or, most commonly, bicycle riding).83

The current “state of the science” continues to change.84 85 The following review provides detailed information on studies related to factors associated with vulvodynia.

Introduction

In the past thirty years, the multifactorial etiology of vulvodynia, involving the complex interplay between genetic, neurological, musculoskeletal, environmental, immunological, and psychosocial factors has come into view. Failure to capture the persistently elusive causes and, therefore, the management of vulvodynia, relates to lack of basic scientific knowledge about the potentials and perils of the human vulva and vagina. Identification of “factors” associated with vulvodynia, listed in the 2015 Consensus Terminology and Classification Statement, forms the basis of historical and current research represented in this section.86 87 Review of the studies, mostly done to try to comprehend localized provoked vulvodynia/vestibulodynia (LPV/PVD), reveals evolution of thought on the conditions over time. Studies on pudendal nerve compression or entrapment show relationships to both localized and generalized vulvodynia. See Pain Basics for what is known in general about pain neurology.

FACTOR: Inflammation (regionally defined in the vulva/vestibule)

Introduction

Inflammation is not a pathological process; instead, it represents a protective immune response initiated by the evolutionarily conserved innate immune system to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, dead cells, or irritants. Inflammation is strictly regulated by the host. Insufficient inflammation can lead to persistent infection of pathogens, while excessive inflammation can cause chronic or systemic inflammatory diseases. Innate immune function depends upon recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), derived from invading pathogens, and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), induced as a result of endogenous stress, by germline-encoded pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). Activation of PRRs by PAMPs or DAMPs triggers downstream signaling cascades.88

Since inflammation’s defensive mechanisms can cause pain, it has been a natural place to start investigations into the etiology of vulvodynia.

A striking feature of the inflammation of vulvodynia is that, on inspection, the condition cannot be “seen.” The classical diagnostic signs of inflammation, rubor (redness), calor (increased heat), tumor (swelling), dolor (unprovoked pain), and functio laesa (loss of function) are not present on inspection of the vulva of a woman with LPV/PVD. Mild erythema, often fleeting with light touch of the Q-tip, may or may not be present on inspection in the vestibule. However, researchers using either laser Doppler perfusion imaging or cross polarized light found enhanced blood flow, (erythema) below levels of clinical detection in the vestibules of patients with LPV/PVD, representing the possibility of inflammation.89 90 Studies are now focusing on molecular markers for inflammation to understand possible etiologies and effects of LPV/PVD: proinflammatory cytokines, neurokines, eicosanoids such as prostaglandin (PG)E2, and/or chemokines, in addition to the presence of mast cells and regional neural proliferation which have long been studied.91

Foster, et al. noted the remarkable similarity of clinical findings in patients with LPV/PVD, who present with marked mechanical allodynia in close juxtaposition to pain-free skin and mucosa.92 They suggest that the normal vulva and vagina exhibit ongoing low-grade inflammation as a defense against pathogens introduced with penetrative sexual contact or migrated from nearby body sites such as the anus.93 94

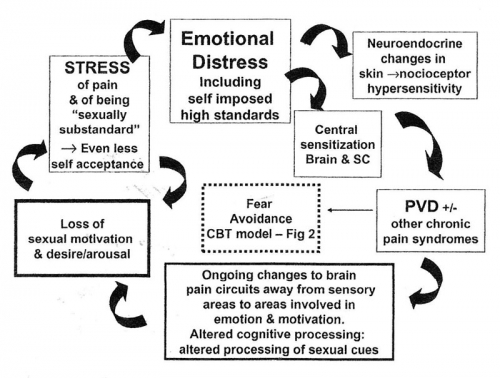

In his latest research, David Foster proposes that an inflammatory trigger, such as Candida albicans, promotes a cascade effect as follows:95

- Candida albicans stimulates…

- Proinflammatory cell migration and cellular immune response amplification in the vestibule which leads to…

- Production and release of pain-inducing substances with…

- Regional hyperinnervation of C fibers and associated TRPV1 channel increase, leading to…

- Lowering of pain thresholds, then…

- Gradual development of central sensitization, causing…

- Somatization, depression, anxiety, and hypervigilance, terminating in…

- Tightened pelvic floor muscles and increased pain, and sometimes culminating in…

- Other chronic pain disorders.

Early research studies on inflammation: 1986-2019 and Research study: Pro-inflammatory Cell Migration to the Vestibule

“Vulvar vestibulitis” was embraced as an early name for LPV/PVD, because vulvar biopsies of women with LPV/PVD showed inflammatory immune cells, mainly T-lymphocytes (related to non-specific inflammation).96 Mast cells, key players in the inflammatory response as they activate release of other inflammatory mediators, then became the object of many studies.

In 1988, small numbers of mast cells were noted in biopsies from vulvodynia cases with lower numbers in controls. The vulvar tissue showed an increased lymphocytic infiltration, considered inflammatory, in patients, with reduced infiltrate in controls.97 In 1996, a significant number of mast cells were noted in surgical (vestibulectomy) cases compared with post colporrhaphy controls. These researchers suggested a possible inflammatory association between mast cell triggering in both interstitial cystitis (bladder pain syndrome) and LPV/PVD.99 Then, 12 cases and controls studied by Chadha, et al. in 1998 revealed an increased inflammatory infiltrate, mostly lymphocytes. Plasma cells, mast cells and some monocytes were also present.100 By 2004, one of the most frequent findings across pelvic pain populations was evidence of increased mast cell count and/or mast cell degranulation, as well as nerve fiber proliferation, thought to be associated with chronic inflammation.101 102 However, non-specific inflammation was not observed in studies that followed.103 In 2007, a British study104 found no evidence of inflammation, and “no more-itis” came to the front again, with research turning its focus to pain. More recently, in 2015, Tommola et al. completed cross-sectional studies of vestibular biopsies with immunotyping of T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, dendritic cells, and mast cells. Lymphocytic infiltration density was significantly greater in vulvodynia cases compared with controls. Dendritic cells, B lymphocytes, plasma cells, and lymphoid germinal centers were greater in cases. Mast cells and macrophages did not differ between cases and controls.105 A year later, Tommola, et al. completed a second cross sectional study of vestibular biopsies from cases and controls that showed an increase in inflammatory cells (lymphocytes etc.), but mast cells and macrophages did not differ between cases and controls.106

A 2019 study now suggests that macrophages may contribute to the hyperinnervation and nociceptive sensitization of vulvodynia, and warrant further study.107 Macrophages are described as pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory, and can have multiple roles in the induction and resolution of inflammation. Their function can be broadly fixed, then can alter rapidly in response to the microenvironment. In addition to phagocytosis of foreign pathogens and apoptotic cells, macrophages release hundreds of effector molecules and proteins including growth factors, cytokines and chemokines.108

Continuing research studies: Changes in the vulvar biochemical milieu by regional production and release of pro-inflammatory, pain-inducing substances: cytokine, neurokine, chemokine, or prostanoid signals increase pain.

Nociceptors generate electric signals to convey the quality, duration, and intensity of noxious stimulation. Variability in nociception results from specialized receptor proteins and ion channels located on nerve endings; these identify several types of information, e.g. heat, pressure, acidity, chemicals, differentiated by the molecular markers they express.109 Ongoing nociceptive signals could alter the ion channel of these peripheral pre-terminal axons, modifying the conduction of nerve fibers, further lowering the threshold in nociceptors for pain signals,110 with ongoing elevation of pro-inflammatory substances.111 At first, assays for pro-inflammatory molecules in vulvovaginal samples had varying and inconsistent results, with some studies showing an elevation in the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1b and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Others showed lower levels of TNF-α and similar levels of IL-1b among patients and controls. In 1997, Foster and Hasday reported that vulvar fibroblasts yielded high levels of IL-6, IL-8, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) after stimulation by irritants in both women with LPV/PVD and controls.112 Ten years later, Foster et al went on to show that vestibular fibroblasts released elevated levels of IL-6 and PGE2 compared to fibroblasts isolated from non-painful vulvar sites. Furthermore, pro-inflammatory mediator production was elevated in LPV/PVD fibroblasts compared with controls.113 Foster’s more recent research follows under Factor: Immunology.

In summary, the evolving research into the inflammatory pathogenesis of vulvodynia has produced ample histological evidence of pro-inflammatory cell migration to the vestibule, although inflammatory infiltrates in general, and mast cell infiltration specifically, have not been found to be consistently increased in all vulvodynia studies.

FACTOR: Immunology

Introduction

The vulva and vaginal canal reveal a unique immune profile that differs from other mucosal sites and elsewhere in the periphery. There is evidence to suggest that an altered immunoinflammatory response may contribute to the etiology of vulvodynia.114

Research studies: history of allergy

The first epidemiological study to report an association between allergic reactions and vulvodynia included 239 women with and 239 women without vulvodynia. From this work, Harlow et al. suggested that women with a history of urticaria, seasonal allergies, or reaction to insect stings appear to be more prone to later development of vulvodynia than women with no history of these allergic reactions. This association was largely confined to exposures and reactions that occurred before the first onset of vulvar pain, suggesting that allergenic exposures could be a marker for or a factor involved in the development of vulvodynia. Of note, they also observed that a history of other skin conditions, not as strongly related to an immune response, generally was not associated with the risk of vulvodynia.115 Study of the recognized mediator of cutaneous urticaria intensified. Even greater attention was then focused on mast cells which release heparinase with allergic inflammation, as well as histamine, tryptase, bradykinin, and nerve growth factor (NGF) which causes nerve fiber sprouting. Increased mast cells with increased nerve fiber density in cases of vulvodynia were also reported by Bornstein, et al. 116

In 2010, Bornstein’s findings were replicated by Goetsch who found significant increases in inflammatory cell infiltrate, mast cell density, and nerve fiber density.117 A year later, a study without controls also reported increased mast cells in samples from vulvodynia patients.118 Not all studies, however, supported the presence of inflammatory cells and increased mast cell density. No difference in mast cells or the extent of inflammation was noted in 24 cases and 16 controls.119

Research study: the thymus in relationship to vulvodynia

The thymus is a mediastinal organ where young hematopoietic stem cell-derived thymocytes migrate to mature into naïve nonself-reactive T-cells. T-cells mastermind powerful, antigen specific immune activities – B cell production, and macrophage remodeling of tissues. At puberty, the thymus begins to atrophy and produces fewer mature T-cells. Pursuing the question of an association of vulvodynia with an altered immunoinflammatory system in women with vulvodynia and abnormal thymic function, researchers evaluated thymic function in cases of clinically confirmed vulvodynia and healthy controls. Their findings suggest that at younger ages, women with vulvodynia have higher thymic output and a more precipitous decline of thymic function than those without vulvodynia. It also seems that a strong immune inflammatory response is present proximate to the onset of vulvar pain and may wane subsequently over time.120

Research studies: recurrent vulvovaginal Candida albicans

Candida is both a known cause (infection) of vulvar pain, and an associated factor in vulvodynia. Various studies described findings associating vulvodynia with a possible deficient immune response that resulted in recurrent vulvovaginal Candida infections (RVVC) (more than 3 documented episodes of Candida in one year) and subsequent development of LPV/PVD. An inability to clear vulvovaginal yeast infections and the resulting chronic inflammation may lead to LPV/PVD development. (Studies supporting genetically-related findings are discussed under Factor: Genetics). Early investigations confirmed the anticipated increase in incidence of vulvovaginal candidiasis in women with LPV/PVD compared with female controls.121 122 123

Harlow et al. have shown that a positive connection exists between yeast infections prior to and after the diagnosis of vulvodynia, although the relationship varies based on the accuracy of women’s recalled diagnosis of yeast infections. Uncovering the degree of accuracy will require validation studies to determine 1) the extent to which classification of self-reported yeast infections differs between women with and without vulvodynia, and 2) whether self-reported yeast infection is a valid tool for comparative (or any) study.124 Intricate work by Foster et al.125 edifies our understanding of the complex relationship between pain and immune function with the novel observation that the vulvar vestibule (doorway to the vagina) exhibits a highly localized and tissue-specific proinflammatory response in healthy women, a response further amplified in women with LPV/PVD. The mechanisms underlying LPV/PVD need more work, despite unequivocal evidence for low-grade inflammation, altered peptidergic vulvar C-fiber innervation, and genetic susceptibilities contributing to abnormal inflammatory constellations, but Candida albicans is a known cause of inflammation across species and is implicated in more than 90% of vulvovaginal yeast infections in women. High incidence of recurrent Candida in women with LPV/PVD promoted the theory that yeast-induced vulvovaginal inflammation may underlie peripheral and possibly central sensitization of primary afferent nerve endings at the vestibule. Foster, et al. also reported that pro-inflammatory mediator production of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and prostaglandin E2(PGE2) was robustly increased in LPV/PVD fibroblasts compared with controls. When fibroblasts were challenged with live yeast species, pro-inflammatory mediator production again rose, and the response was highly predictive of clinically measured pain thresholds.126 This work is a timely and topical advance in our understanding of site-specific mucosal immunity and also the ability to rapidly detect pathogens at a critical anatomic gateway to the reproductive tract.

It is possible that the vestibule of LPV/PVD patients is inherently more sensitive to yeast; even a subclinical Candida infection might trigger a maladaptive immune response in these fibroblasts. Foster and Falsetta’s group evaluated the signaling pathways involved in the recognition of yeast by vestibular fibroblasts that are present during chronic infection. They found that vestibular fibroblasts from LPV/PVD patients express elevated levels of Dectin-1, a surface receptor that binds C. albicans. They also demonstrated that blocking the function or expression of Dectin-1 in vitro led to a significant decrease in IL-6 and PGE2 production.127

Effective antifungal treatment, represented by a negative culture for Candida post-treatment, often does not eradicate symptoms. With that in mind, an ongoing search began for immunological and inflammatory explanations for long lasting central sensitization after resolution of acute inflammation.128

This search is further discussed under Factor: Genetics below.

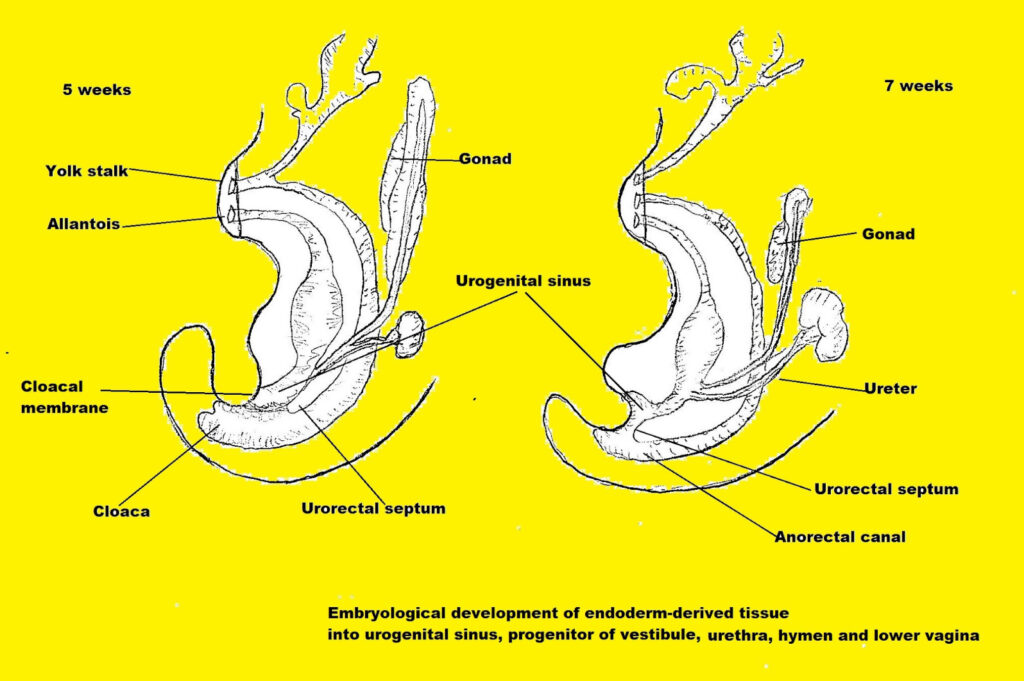

FACTOR: Embryology (not a Factor in the 2015 Consensus, but references to it occur now in the literature in relationship to vulvar pain).

Introduction

The embryological development of the vulva may be involved in the development of vulvodynia. During the fifth week of gestation, the urorectal septum divides the cloaca, creating the perineum and tissue folds on each side of the cloaca. The anterior folds form the urogenital sinus; posteriorly the folds form the anorectal canal. From the urogenital sinus comes the vaginal vestibule, where the urethra, vagina, and greater vestibular glands open. It has been hypothesized that the endoderm-derived tissue comprising the vestibule, urethra, hymen, and lower third of the vagina has special immunologically protective characteristics.129 130

More than one scientist has proposed that these tissues, all derived from the embryological urogenital sinus, are immunologically unique, a protective doorway to the vagina with special defensive powers.131 132 133 (The hymen, part of the endoderm-derived group, has no known anatomical or physiological function, although prepubertal protection from infection has been hypothesized).134

Cases of interstitial cystitis co-existing with vulvodynia have been reported, raising the question of whether the two painful conditions could represent a congenital anomaly: a disorder of urogenital sinus-derived endothelium.135 Other structures derived from endoderm, including bladder and anterior urethral wall may also exhibit unique immune properties.136

FACTOR: Genetics

Introduction

Genetics is an emerging discipline in relationship to vulvodynia; it remains to be seen whether all the answers we expect regarding chronic pain from genetic sources materialize. Genetic interactions, genetic-environment interactions, and epigenetic variants can involve multiple genes. At this point it is difficult to reliably estimate the genetic component of chronic pain conditions because of the complexity of these interactions.137

Research studies: genetic studies revealing polymorphisms

Reliably estimating the role of the emerging and complex discipline of genetics in vulvodynia is an arduous undertaking. Genetic interactions can involve multiple genes, as well as genetic polymorphisms (variations of the gene) and epigenetic variants, (heritable changes that do not affect the DNA sequence but change gene expression, e.g., addition of a methyl group to part of the gene molecule).138 To date, genetic studies related to vulvodynia have focused on several possible mechanisms that could form a foundation for genetic predisposition:139

- Genetic polymorphisms that increase the risk of candidiasis or other infections

- Genetic changes that permit prolonged or exaggerated inflammation

- Altered immunological response

The role of genetics in common chronic pain conditions suggests minor contributions from a large number of single nucleotide polymorphisms representing different functional pathways. 140

A genetic profile of women suffering from vulvodynia, especially looking at genetic polymorphisms from genes coding for cytokines, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and interleukin-1 beta, and gene coding for mannose-binding lectin (MBL), is discussed below. These polymorphisms result in a stronger inflammatory response, making these women highly susceptible to pain.141

In 2000, Jeremias et al. noted a higher frequency of certain alleles in interleukin-1B and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist polymorphic genes among women with vulvodynia.142 Clinical and laboratory-based studies then showed that women with vulvodynia exhibit lower serological levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. This finding suggests that these women may be at a greater risk of a proinflammatory immune response resulting from their inability to terminate an inflammatory event involving IL-1 production.143 The same researchers confirmed their findings with another genetic study of IL-1.144

In the innate immune system which comprises the initial defense against microbial invasion, a major component of antimicrobial innate immunity is mannose-binding lectin (MBL). MBL is present in the systemic circulation.145 146

NALP3 inflammosome and mannose binding lectin (MBL) represent an innate immune system of receptors/sensors that regulate the activation of caspase-1. This enzyme proteolytically activates the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta and IL-18.). MBL and the NALP3 inflammasone induce inflammation in response to infectious microbes and molecules from host proteins.147 NALP3 inflammosome and MBL are also associated with defense against Candida species. The genes that code for each are polymorphic. Women with LPV/PVD had a higher MBL variant allele frequency than controls. MBL specifically binds to mannose and N-acetyl-glucosamine molecules on microbial surfaces, initiating complement-dependent microbial killing and microbial opsonization via MBL-recognizing receptors on the surface of macrophages and dendritic cells.148 149 Individuals with decreased circulating levels of MBL were shown to possess variant alleles in exon I of the MBL gene. A single nucleotide substitution at codon 54 was associated with an increased rate of infection.150 Subsequent investigations, however, have shown conflicting results.151

FACTOR: Hormonal influences

Introduction

Gonadal hormones are thought to be indispensable cornerstones of normal development and function, and it appears that no body region, no neuronal circuit, and virtually no cell is unaffected by them. Thus, increasing awareness toward estrogens appears to be obligatory. 152

Research studies: estrogen and nociception

Estrogen is involved in multiple roles in reproduction and gynecology not covered here. Sensation and nociception occur at the peripheral, spinal, and supraspinal levels.153 In the periphery, rapid 17-beta estradiol signaling of membrane bound ER-alpha and -beta is important in mechanical nociception.154 Nociceptor signaling may vary across the menstrual cycle as hormone levels fluctuate. High levels of circulating estrogen during the preovulatory period enhance structural integrity of tissue and estrogenic inhibition of purinoreceptors (P2X3s) may allow genital tissue to withstand the physically rigorous act of intercourse.155

A wide array of functions can be attributed to estrogens, including the dramatic change from non-painful to painful mechanical pressure. This pain threshold is encoded by voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) and purinoreceptors (P2X3s) located near nociceptive nerve endings.. The rapid switching message from non-painful to painful mechanical pressure encoded by the P2X3s activates the rapid release of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), resulting in a rapid inflammatory response. Inflammation alters the voltage dependence of the P2X3 receptors and enhances their activity, boosting neuronal hypersensitivity and pain. Reduced mechanical pain thresholds may reflect inadequate ER-alpha regulation of P2X3, leading to excessive activity of P2X3 and more pain. Support for this hypothesis includes data indicating that postmenopausal women show that tissue depletion of estrogen is related to mechanical allodynia.156 157 158

Depletion of female gonadal hormones in rodents induces mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity that parallels a threefold increase of P2X3 receptor expression in the dorsal root ganglion.159

Results of diminished or blocked estrogen- what happens when there is not enough?

It is well known that vulvar and vaginal tissues are responsive and dependent on sex steroids for integrity and function; a deficiency in circulating estrogen leads to changes in the anatomy and physiology in the vagina. Both natural and iatrogenic causes of decreased sex steroids can lead to symptomatic physiologic change. Clearly, the most common cause of lowered sex steroids in women is menopause. Lactational anovulation, anorexia with hypothalamic amenorrhea, and hyperprolactinemia are other important natural causes.160 Surgical factors including oophorectomy and hysterectomy without oophorectomy come into play, as well.161 American women also have a lifetime risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer; 70-80% of breast cancer tumors express the estrogen receptor (ER) and/or the progesterone receptor. Long term systemic anti-estrogen therapy is often an indicated therapy. The regimen usually consists of a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) such as tamoxifen for premenopausal women or an aromatase inhibitor (AI) for postmenopausal women. Both classes of drugs suppress circulating estrogen, possibly predisposing patients to dyspareunia.162

Spironolactone, another hormone modulating treatment for androgen mediated cutaneous disorders (AMCD) such as hair loss, hirsutism, and acne, is another possible contributor to dyspareunia. Spironolactone is an androgen antagonist which decreases the effect of endogenous androgen by inhibition of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone binding to androgen receptors. While approved for the treatment of hypertension, spironolactone is increasingly used in the treatment of AMCD. A recent case report has linked spironolactone with hormonally associated vestibulodynia and decreased sexual arousal. Another 17-spironolactone chemically similar to spironolactone is the progestin in the oral contraceptive Yasmin. Yasmin has been shown to reduce the frequency of intercourse and orgasm, and possibly introduce hormonally associated vulvodynia.163

Research studies: sex steroids and vestibulodynia: The role of CHC’s and LPV/PVD

A great deal of research has focused on the possible influence of combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) use on increased risk of vulvodynia. A polymorphism in the androgen receptor significantly raises the risk of developing combined hormonal contraceptive-induced LPV/PVD.164 CHC formulated with an estrogen and a progesterone lead to a lower serum estradiol and free testosterone by decreasing ovarian production of estrogen and total testosterone and by inducing the liver to produce increased levels of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG). In addition, some CHCs contain synthetic progestins that act as testosterone antagonists at the androgen receptor.165

In addition, it has been shown that CHCs induce morphologic changes in the vestibular mucosa, raising its vulnerability to mechanical strain.166 CHC use has also been associated with decreases in mechanical pain thresholds167 and with decreasing clitoral size, labial thickness, and introital diameter. All of these reductions led to decreased orgasm, lessened sexual frequency, limited lubrication, and increased dyspareunia associated with CHCs.168

It follows, with all the effects on sex steroids, that researchers have looked for a connection between use of CHCs and development of LPV/PVD. Women who used CHCs before the age of 17 years had a relative risk of 11 of developing LPV/PVD.169 Both Bouchard, et al.170 and Harlow, et al. confirmed in case-controlled studies that early CHC use significantly increases the risk of developing LPV/PVD.171 In one study, use of CHCs containing ethinyl estradiol at a dose of <20 mcg significantly increased the risk of LPV/PVD.172 There is also a case series of 50 women who developed LPV/PVD while on CHCs; treatment with topical estradiol and testosterone was successful after cessation of the CHC.173 However, there is some conflicting evidence about the role of CHC, with one population-based study of 906 women showing no increase in risk of vulvodynia.174

Research studies: estrogen and postmenopausal pain

Attention to lack of estrogen and postmenopausal dyspareunia led to the first study to systematically investigate the clinical attributes of dyspareunia pain (location, sensory quality, and intensity) in postmenopausal women, demonstrating that, similar to premenopausal dyspareunia, it is a heterogeneous condition. A study of 182 postmenopausal women 45-78 years old, found that by looking at all aspects of the pain, six subgroups could be identified. Clusters V1, V2, and V3 featured pain confined to the vulvar vestibule. Clusters V4-V6 experienced genito-pelvic pain. The predominance of provoked vestibular pain (97.8%) was consistent with epidemiological and clinical studies reporting that superficial dyspareunia is the most frequently found subtype in postmenopausal women. However, pain in other genital and pelvic locations was noted in a significant proportion (22-32% in the patient and 8.5% in the general population). Hence, the familiar division of superficial and deep dyspareunia in postmenopausal women is not supported. Rather, pain may be restricted to the vulvar vestibule, or occur in combination of vestibular and other genital and pelvic sites. And this group V1 may be derived from classic LPV/PVD in menopausal women, while the V2 group may be showing the clinical attributes associated with vulvovaginal atrophy. The study is limited by its lack of controls.175

Another study of pain in postmenopausal women emphasizes that all postmenopausal vulvar pain cannot be attributed to vulvovaginal atrophy. Using data from 371 participants ages 42–52 years at the Michigan site of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), researchers aimed to provide population-based information looking at the associations of vaginal symptoms, serum hormone levels and hormone use. 40% of the women reported chronic vulvar pain; 13.7% indicated past but not current pain, or short duration vulvar pain symptoms. Of those with chronic pain, 25% did not report dryness. Use of hormones during the preceding year was more likely in women with current, chronic, and past/short duration vulvar pain symptoms (13.3%, 17.6% and 20% respectively: p < .01). With each log unit drop in serum dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate and testosterone levels, there were increased relative odds of current vulvar pain symptoms. Despite the possibility of inadequate hormonal treatment in some cases, vulvar pain unresponsive to hormone therapy, supports the presence of a chronic pain condition, such as vulvodynia, that mandates alternative, non-hormonal treatment measures. The most common complaint associated with vulvovaginal atrophy, vaginal dryness, was not reported by >25% of the women with current chronic vulvar pain. Elevated odds of reporting chronic vulvar pain were associated with lower average DHEA-S and testosterone levels prior to the presence of vulvar pain symptoms. These findings yield increased evidence that chronic vulvar pain in postmenopausal women has a multi-variant etiology, and may not be explained by estrogen deficiency and atrophy alone. Postmenopausal women may be experiencing new onset, exacerbated and/or long-term chronic vulvar pain consistent with vulvodynia. A trial of hormone therapy is advised for women with both pain and atrophy, with alternative vulvodynia treatments in those who have no pain improvement with hormonal therapy.176

From 2008-2016, Goetsch, et al. followed sixteen cases of burning vulvar pain that remitted with prolonged estrogen in postmenopausal women 44-85 years old. 9 women had premenopausal oophorectomy. Each patient received nightly estradiol either as a topical cream to the vestibule, or continuously by transdermal patch. They were followed by serial examinations and telephone contact follow-up over eight years. The women were taught how to apply local 4% lidocaine prior to the estradiol if needed. Continuous estradiol use was associated with reduced pain in all patients, with slow progression of improvement. Prolonged therapy over an average of eight months eliminated the incessant burning pain in 12 (70%) women. Four women reached a plateau with pain scores of 2-3 out of 10. Two women required mucosal excision after estradiol therapy had improved them initially. The author points out the marked trophic effect on genital pain nerves related to lack of estrogen; years of gradually mounting nerve growth may require much longer and stronger treatment to prune nerves and regenerate normal function. She raises the concern that avoidance of estrogen may have long-term consequences for urogenital tissue.177

Liao, et al. have elucidated the physiology of vestibular nerve sprouting in premenopausal women. A local renin angiotensin system generates a local trophic stimulus achieving angiotensin II receptor activation in mechanoreceptors, spawning nerve proliferation.178

Examination of vaginal tissues in women undergoing anterior colporrhaphy revealed that densities of both autonomic and sensory nerves in the vaginal submucosa are related to estrogen status.179 All women were free of vaginal pain; tissues showed greatest nerve densities when there was no estrogen exposure, moderate densities with systemic estrogen therapy, and fewest with topical estradiol therapy. We also need to recognize that increased autonomic innervation may influence atrophy by way of vascular supply, mass and smooth muscle tone in postmenopausal vaginas, distinct from the pain consequences of increased nociceptor densities.

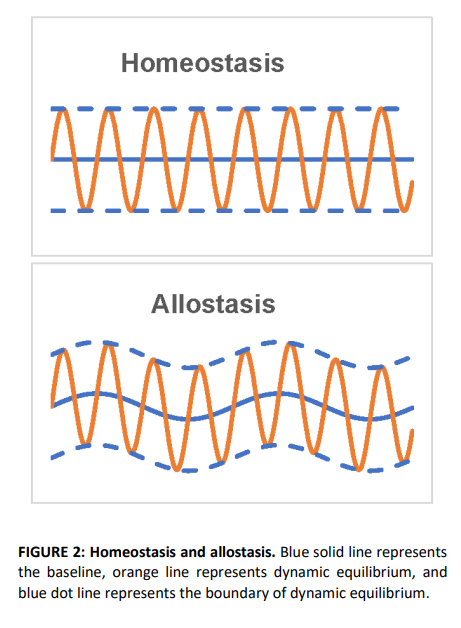

The unevenness demonstrated by these women may appear to be a morass of presentations and responses, but is really a status quo for end-organ sensitivity to estrogen, a well known idiosyncrasy of the hormone. It would appear that the criteria for vestibular homeostasis varies widely among women.180

The common complaints in 50% of postmenopausal women with dyspareunia have always been attributed to vulvovaginal atrophy. The current term Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) covers more symptoms than atrophy alone and promotes a more detailed exploration of the dysfunctions occurring in menopausal women. Reports from postmenopausal women of symptoms affecting multiple regions of the genitourinary tract are common. While the FDA authorizes local estrogen cream therapy to be inserted in the upper vagina, one wonders how helpful intravaginal estradiol is for the labia, introitus, urethra and bladder. And often inadequate attention is paid to other diagnoses that may contribute to dyspareunia such as tenderness of pelvic floor muscles, bladder, and uterus or adnexa.

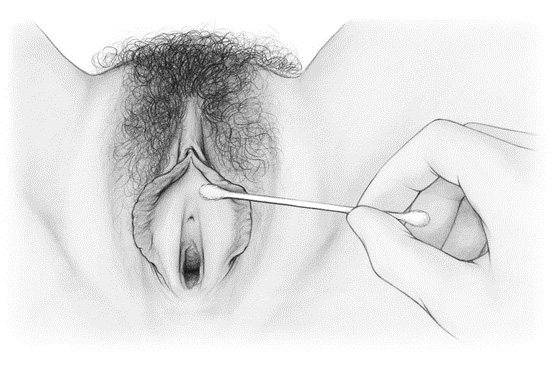

A 2022 study181 aimed to describe the symptoms and physical examination findings in a cohort of women with moderate to severe dyspareunia being screened for a clinical trial of two strengths of estradiol cream. For 55 women, a modified vulvar Pain Assessment Questionnaire (VPAQ screen) and a 13 item questionnaire created from several validated instruments were used. The Urinary Distress Inventory, the Sandvik Severity Index, the O’Leary/Sant Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index, and the Urinary Tract Symptom Assessment were employed to obtain symptom information. Physical exam and standard pelvic exam were performed along with the tampon test and cotton tipped swab test. 4% lidocaine was applied to all the vestibule for 3 minutes; then the cotton swab test was repeated and scored by NRS. Pelvic floor muscles were evaluated.

Mean age of the women was 59.5 years. Mean pain scores with intercourse was 7.3 out of 10 by numeric rating scale. 30 of 55 women had stopped intercourse for lengthy periods due to pain. 70% of the women had used estrogen after menopause, citing dyspareunia in most cases. 70% of users reported failure to obtain relief.

49% of women reported symptoms affecting the outer vulva, by use of a detailed drawing. Dryness was the most common symptom (58%), while 20% reported fissures, splits, or tears. Lower urinary tract symptoms occurred in 45 women (82%).

Physical findings in the majority were consistent with vulvovaginal atrophy. Tenderness was localized to the vulvar vestibule. Fifty of 55 women (91%) reported pain >3 at some location adjacent to the hymen. Examination tenderness was fully extinguishable in every participant with a 3 minute application of 4% lidocaine. Mean vaginal pH was 5.6. Pelvic floor muscle tenderness was the second most common location of tenderness.

Burning was the most frequently reported descriptor. Dryness presented a dilemma in interpretation. It is not a listed descriptor in the McGill Pain Questionnaire; it is a descriptor in the VPAQ. Because the term “dry” is the most common symptom attributed to VVA/GSM participants were requested to score “dry” as a descriptor of intercourse. Along with “burning,” “dry” was a similarly frequent descriptor endorsed by this cohort of women for both spontaneous pain and insertional pain.

A minority of studies have assessed the consequences of estrogen deficiency in the nerves of the human genital tract. The epithelium of the human vulvar vestibule is richly innervated,182 with documented increases in these nerves in postmenopausal dyspareunia, confirmed to be sensory nerves in LPV/PVD.183 In contrast, the innervation of the human vagina consists of submucosal autonomic nerves and only rare pain nerves. It is this vestibular innervation with sensory nerves that yields a credible explanation for the tender vestibular tissue reaction to topical lidocaine.

This finding that the primary location of genital tract tenderness is the vulvar vestibule promotes consideration of targeted therapy to the introitus as a treatment for postmenopausal dyspareunia. Findings that topical lidocaine extinguishes vestibular tenderness indicate that the study of superficial nociceptor function in the GU tract may lead to an improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms of dyspareunia. Increased focus in GSM research on specific GU structures may help assign common complaints to locations and lead to recognition that symptoms vary and relate to the duration and degree of estrogen deficiency. More precise therapy regimens may thereby emerge.184

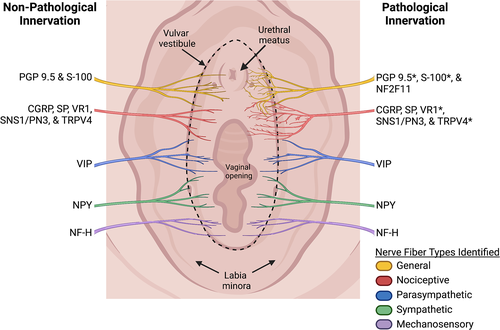

FACTOR: Neurologic mechanisms

Introduction

Advances in understanding vulvodynia have resulted from the study of neurology and pain. The intricacies of vulvovaginal sensation, steps toward understanding neural circuitry, peripheral and central sensitization, and the critical role of the central, peripheral, and supraspinal regions in the interpretation of pain: all have contributed hugely to advance our work.

From the beginning it is important to recognize that the nervous system is not a static system.

Neuroplasticity is a process that is making neural pathways more difficult to delineate. It involves the adaptive ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections after injuries. 185

Research studies: Painful genital sensation: considering subgroups of vulvodynia.

Studies related to LPV/PVD have focused primarily on pain limited to the vulvar vestibule, despite the understanding that vaginal muscle tone is either affected by vestibular pain or contributes to it.186 187 Some researchers, however, are looking into associated anatomical sites, hypothesizing that their contribution to the diagnosis of vulvodynia is being overlooked. Falsetta and Foster, et al, proposed that the vestibule is uniquely immunologically defensive to pathogens, causing inflammation that might lead to pain.188 189 Farmer, in 2013, also drew attention to the special immunological characteristics of the vestibule, in its position as gateway to the vagina.190

This research draws attention to the question of whether the term vestibulodynia is a limiting one. Farmer explores evaluation in her controlled trial, of pressure applied to the vagina as well as to the vestibule, finding that patients with LPV/PVD experience pain with low pressure in the vagina in comparison with controls whose pain sensation occurs under much more pressure.

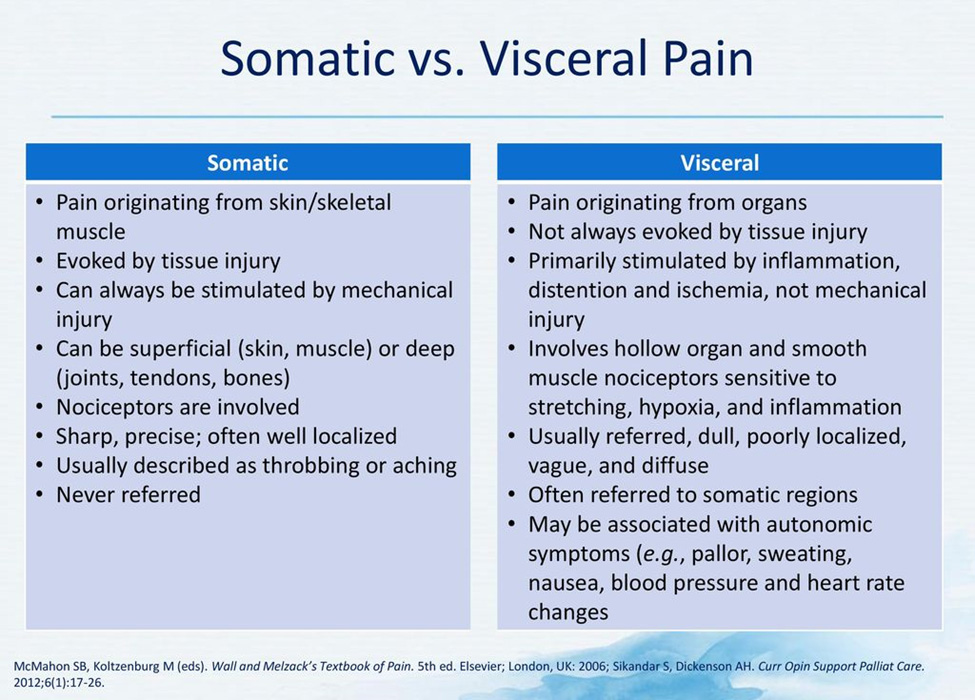

Vulvar pain is both a somatic and visceral disorder. Pain hypersensitivity promoted by light mechanical vulvar touch (vulvar allodynia) is characteristic of provoked vestibulodynia (LPV/PVD). Pain brought on by distension of the vagina by digital, penile, or mechanical penetration (vaginal allodynia) destroys the pleasure of sexual intercourse, makes tampon use impossible and fosters a search for relief. Pain in the vestibule in some women can be caused by slight touch (sitting or tight-fitting clothing), whereas in others it is caused only by vaginal penetration during sexual intercourse, tampon insertion, or gynecological examination, resulting in dyspareunia or a complete inability to have intercourse.191

Dyspareunia involves more than vulvar hypersensitivity. Vaginal allodynia is seldom mentioned in LPV/PVD research, even though we have learned that pain with intercourse is not necessarily alleviated with relief of experimentally induced vulvar pain.192 It is not yet known whether vulvar mechanical allodynia is a suitable analog to natural vaginal distension, a predominant source of LPV/PVD pain.193

Measuring static mechanical allodynia requires the correlation of discrete stimulus intensity to a perceived magnitude of pain. In 2013, to study psychophysical properties of pain, Farmer et al measured static (fixed) as well as dynamic (time varying) characteristics of somatic and visceral genital sensation in women with LPV/PVD and matched controls. Women judged varying degrees of painful and non-painful sensation of the vulva and vagina. A linear potentiometer with a spring calibrated to exert the desired pressure was used for vulvar testing. Vaginal distention was achieved with physiotherapeutic dilators.194 All women were provided with experience in rating different intensities of vulvar pain and vaginal sensation so that variability in individual perceived genital sensation would be constant across participants.

Women used a hand attached device to indicate the amount of discomfort experienced with a touch or pressure stimulus to complete a systematic comparison of experimental vulvar touch vs vaginal distension pain in the effort to determine whether punctate pressure testing accurately simulates the naturalistic pain of women with LPV/PVD during intercourse in comparison to healthy women. The distinction between vulvar touch and pain is largely determined by the stimulus intensity, with substantial interindividual variability in the amount of force required to elicit pain. The control group (“normal women”) could tolerate greater amounts of force without perceiving vulvar pressure to be painful. In addition, the mean slope values that show the stimulus-response relationship for vulvar touch and pain were roughly equivalent in normal women whereas individual slopes in women with LPV/PVD showed greater pain perception, sooner, than in controls. Increases in pressure, whether painful or not, and the subjective quality of vulvar pain were appraised in a similar manner. (See next study). The same adjectives used frequently by women with LPV/PVD: “burning“ and “sharp,” were used by healthy women, raising the possibility that provoked vulvar touch, pressure, and subjective quality of pain feel quantitatively similar.195

Research studies: Sensory deviations in perception of vulvar pressure and vaginal distension in LPV/PVD

Study of vulvar pressure and vaginal distension permitted discrimination between sensory characteristics of innocuous genital somatic (vulvar) touch and innocuous visceral (vaginal) distention. Similar to vaginal distension in animal models, researchers found that healthy women could reliably differentiate between perceived levels of fullness with varying dilator volumes, suggesting transmission of innocuous stimuli. Their ability to recognize variation accurately in vaginal fullness exceeded their discrimination of vulvar touch levels. The difference in vulvar and vaginal discrimination shows that in healthy women vaginal distension perception reflects a distinct component of visceral sensation, resulting from dilator insertion. LPV/PVD patients showed a markedly slower rate of perception of non-painful touch in comparison to touch perceptions in controls. Yet both controls and LPV/PVD subjects show compatible time constants and thresholds in response to painful stimuli. LPV/PVD women identify fullness at significantly reduced distension volumes compared to controls and compared to LPV/PVD vaginal pain perception. “Similar to the stimulus-perception patterns for vulvar touch perception, women with PVD required lesser amounts of vaginal distension to perceive equivalent perceptions of vaginal fullness compared to controls.”196

Research studies: Stimulus thresholds in the onset of vulvar and vaginal perception

No group differences were found in the vulvar pressure required to elicit touch. A significantly lower distension volume was required to elicit vaginal fullness perceptions in women with LPV/PVD compared to controls.

As with animal vaginal distension data, Farmer et al. identified the ability in healthy women to accurately determine the differences between perceived levels of fullness with varying dilator volumes, suggesting transmission of innocuous stimulus information. And, remarkably, their ability to discern variation in vaginal fullness was superior to their discrimination of levels of vulvar touch.

The pain of vaginal distension arises from recruitment of primary visceral afferent circuitry and some pudendal somatic innervation near the introitus.197 Vaginal distension perception, as mentioned above, demonstrates a distinct component of visceral sensation, different from that of vulvar stimulation from insertion of a dilator. In animal studies, regional differences in sensory acuity are a familiar finding; vaginal visceral sensation has been characterized as diffusely localized and less temporally distinct than somatic. The capacity of a healthy woman to accurately discriminate levels of vaginal distension promotes the novel concept that sensory properties of the vagina differ from those of other visceral structures.198

Research studies: Clinical parameters associated with genital perception in LPV/PVD

Women with LPV/PVD perceived vulvar touch and pain in response to far less pressure than healthy women. Static sensory measures are therefore adequate to confirm LPV/PVD pain as a form of vulvar allodynia and vulvar hyperalgesia. Because this heightened pain perception is relative to the peak stimulus intensity, it is possible that this early peak reflects the cognitive and emotional responses to the experience of pain, rather than the magnitude of nerve fiber activation at the vulva.199

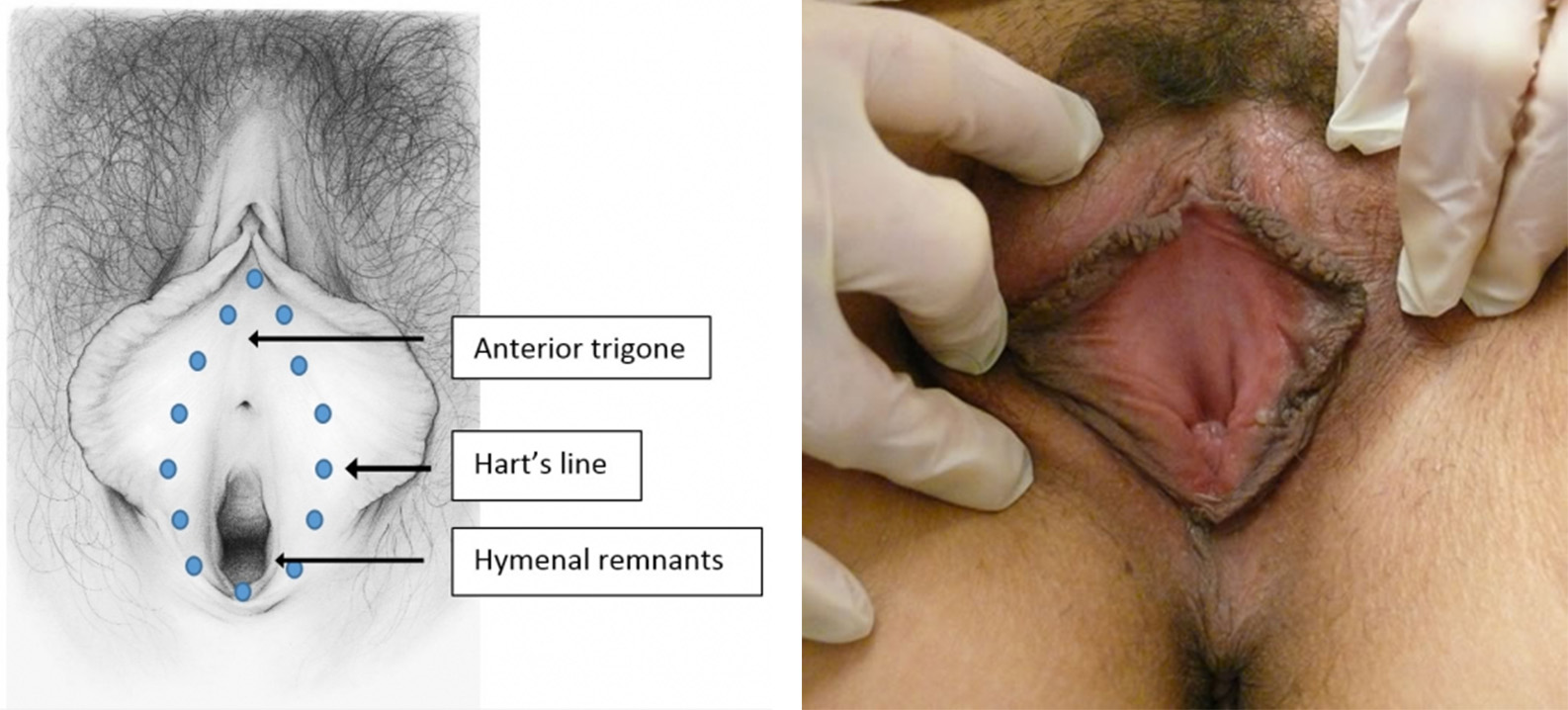

Research studies: Regional hyperinnervation of C fibers