Introduction

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder primarily of the anogenital areas but also the general skin (6-20%).1 It rarely affects mucous membranes. LS results in inflammation, marked hypopigmentation, tissue thinning, areas of thickening and hyperplasia and scarring. Predominant color changes in the skin are white and red. Itching is a hallmark of the condition, but there are many possible presentations and the negative impact on patients is great, particularly in relationship to quality of life and sexuality.2 Untreated LS may progress to loss of normal vulvar architecture, adhesions and fusion of tissue, and the possibility of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) that can lead to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC).3 While there is no cure, treatment can help the patient manage the condition.

A 2023 overview of this condition may be found in the following open access article: De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H, Bieber K, Thaçi D, Ludwig RJ. Lichen sclerosus: The 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 16;10:1106318. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318. PMID: 36873861; PMCID: PMC9978401. (Copy and paste in your browser).

Synonyms for lichen sclerosus are lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS & A), hyperplastic dystrophy, and kraurosis vulvae, older terms that are no longer in use.

Epidemiology

Lichen sclerosus has been identified in patients of all ages including those in the first years of life.4 It is more common in women than in men.5 LS has two peak ages of presentation. The first occurs in prepubertal girls, and the other in postmenopausal women.6 7 Lichen sclerosus may improve with puberty but this is not always the case, as shown in at least one study.8 It has been pointed out that milder, more subtle symptoms in pre-menopausal women may distort the assumption of a bimodal presentation.9 In one study of patients with biopsy-proven LS, the mean age at diagnosis was 32 with onset of symptoms at age 27.10 Long-term follow up is important regardless of age.

The prevalence is difficult to determine since patients with this disease may present to pediatricians, dermatologists, gynecologists, and urologists, and many cases go unreported. Estimates range from 1 in 30 elderly women, to 1 in 59 women in a general gynecology practice, to 1 in 300 to 1000 patients referred to dermatologists.11 12 13 14 15

Etiology

The etiology is unknown but several theories have been proposed.16

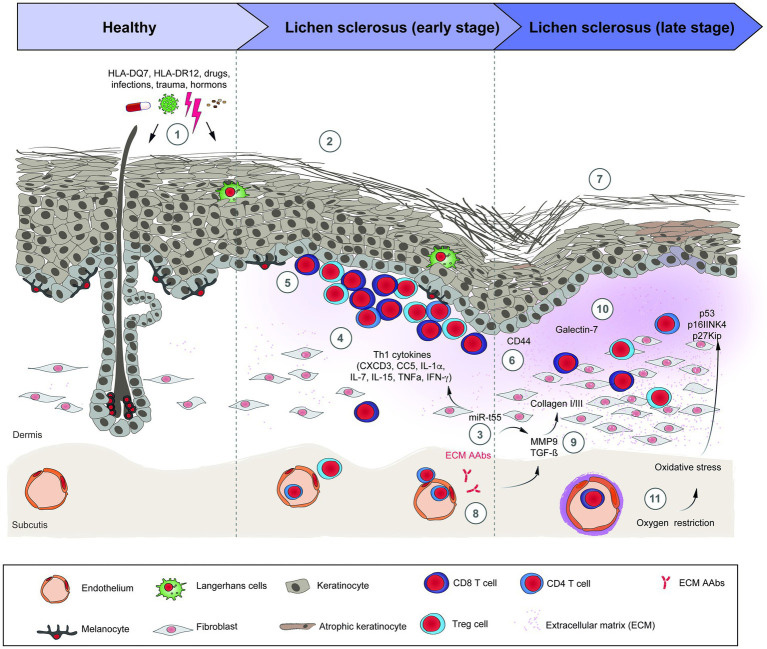

LS has been weakly linked with immune dysregulation and autoimmune disease.17 18 19 Autoimmune diseases occur in 20% of LS patients and 22% of their families, (e.g. thyroid disorders, vitiligo, alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, pernicious anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, and multiple sclerosis).20 21

The genetic contribution to LS is complex. One study has stated that approximately 10% of patients have a relative with the same condition.22 Familial cases have been reported in identical and non-identical twins and siblings, but the inheritance pattern is not clearly established. 23 In the first report of its kind, in two families with a total of 7 members affected by vulvar LS, a type of genomic profiling was done that showed recurrent germ-line variants in 4 genes related to granulomatous and autoimmune diseases and tumor suppressor activities.24 The possible role of TP53 mutations in the development of vulvar cancer in LS is postulated.25 More research with larger studies needs to be done.

Gene regulators of human leukocyte antigens (HLA) have been studied in search of associations between HLA and LS, but none has been found with HLA type 1 antigens. An association has been demonstrated with LS and HLA type 2 antigens that are expressed on immunocompetent cells that normally recognize foreign particles.26 One study in one population of female patients has shown that HLA-A*11, HLA-B*13, HLA-B*15, and HLA-DRB1*12 genotypes have been linked to a higher risk of vulvar LS, and the women carrying HLA-A*11, HLA-B*15, HLA-B*35, and HLA-DRB1*12 genotypes were more susceptible to developing vulvar malignancy.27 However, studies on the influence of HLA classes and HLA-DQ7 are inconsistent.28

T-lymphocytes dominate the inflammatory infiltrate of LS. T-cell receptor gene studies of affected vulvar skin show a monoclonal population of the rearranged gamma chain gene for the T-cell receptor. Experts postulate that this gene rearrangement could explain the increased risk of malignant transformation in individuals with LS.29 Other proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-7, IL-15, and TNF-α have been seen to be upregulated in LS, while anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) are downregulated.30

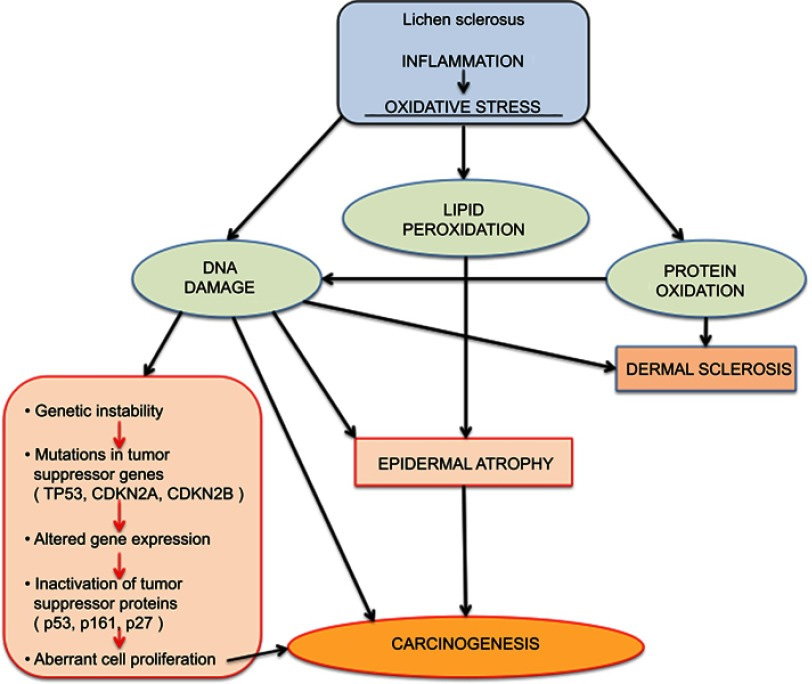

Since the basement membrane is the initial target of the inflammation of LS, the target antigen may lie in that region. Indeed, antibodies against the basement membrane zone have been found in 30% of patients with LS;31 in 67% there are circulating autoantibodies to the endothelial cell adhesion molecule.32 LS and possible associated malignancy may arise from oxidative stress as reactive oxygen species generated from chronic inflammation damage DNA.33 34

Infectious organisms have been postulated but never confirmed. 35

Hormonal influences are questioned since LS is observed in low estrogen physiological states such as prepuberty and postmenopause. There is, however, no association of LS with pregnancy, hysterectomy, or hormone replacement.36 In normal female genitals, the transition from vagina to vulva is marked by an increase in androgen receptors and a decrease in estrogen and progesterone receptors. Vulvar androgen receptor expression may be decreased in a subgroup of individuals with LS.37 38 One study suggested that disturbance of androgen-dependent growth of the vulvar skin by oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), and especially OCPs with anti-androgenic properties, might trigger the early onset of LS in a subgroup of susceptible young women.39 Another study showed preventive benefit from progesterone-only OCPs40 and topical progesterone was even tried as treatment but was not superior to topical corticosteroids.41

Fibroblast proliferation has been found in some studies, but many of these are speculative and do not specify cause versus effect.42

Symptoms and clinical features

The onset may be asymptomatic until the patient has sufficient scarring to produce dyspareunia or even urinary retention.43 Intractable vulvar and/or perianal pruritus and soreness is the most common complaint, as well as dysuria, dyspareunia, and pain on defecation, especially in children or young girls.44 45 The itching can be severe enough to wake the patient at night and to be socially incapacitating by day.46 Uncontrollable scratching may lead to open excoriations, pain, dysuria, and dyspareunia. Itching may be mistaken for yeast infections. Alterations in anatomy may be wrongly attributed to “normal variations in genitalia.”

The classic lesions are circumscribed, ivory white papules and plaques, and atrophic or thickened skin with ecchymoses and hemorrhage from repeated scratching.47 Crinkled skin texture change is classic and generally pathognomonic,

although a shiny, smooth texture also occurs.48 49

If there is repeated scratching, hyperkeratosis and superficial erosions develop. As the disease progresses the labia minora adhere to the interlabial sulci and may disappear.

Fissures may be seen at architectural interfaces or on any surface.

The fissures are painful and can become infected secondarily with bacteria or yeast.50 The inflammation causes pigmentary disturbance with hyperpigmentation in the region of the labia minora, a cause of concern and diagnostic uncertainty since melanoma is then in the differential. 51

The disease may start in the periclitoral area, spreading to involve the entire labia minora and interlabial sulcus, and then extending down through the perineum and the perianal area, forming the typical figure-of-eight pattern.52

One study found LS to be located as follows: on the labia (100%), clitoris (70.4%), perineum (67.9%), buttocks (32.3%), perianal area (32.1%), crural area (8.6%), urethra (3.7%).53 With time, atrophy of all the subcutaneous tissue leads to gradual effacement and eventual complete burying of the clitoris and disappearance of the labia minora. The prepuce of the clitoris may also retract and disappear, leaving the clitoris exposed.

In end-stage disease, the opening of the vagina may be stenosed or even closed.

Patchy involvement of the vulva can occur. In mild or early cases, there may be only simple hypopigmentation.

Sometimes only scattered white guttate papules are seen; in others, there are thick white plaques.54 55

Secondary changes are common. Scratching produces varying degrees of purpura, erosions, and excoriation. Scarred areas may be torn by attempts at sexual intercourse. Some patients show Koebnerization (the induction of new lesions by physical trauma). Repeated scratching causes lichenification that can be frankly warty. The mucous membrane of the vagina is not involved, but there may be some mucosal involvement at the edge of mucocutaneous junctions leading to introital narrowing.56

Unlike lichen planus, LS rarely affects the oral mucosa, but may appear as white plaques on the lips or buccal mucosa.57 10% of patients may have involvement of other body areas, especially the trunk and arms. 58

Cancer risk

The risk of development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma in a woman with LS has been thought to be about 5%.59 A more recent statistic is 3.5-7%60 with a risk of malignancy in the setting of vulvar LS of 65%.61 Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) is understood to be a precursor to malignancy.62 63 64

dVIN in the setting of LS

Assessment of malignant transformation risk in vulvar lichen sclerosus has long been a concern. A retrospective chart review of 129 adult patients with lichen sclerosus who had been under surveillance for a minimum of three years was performed. Squamous cell carcinoma was seen only in non-compliant patients,65 as suggested in two previous studies.66 67 A 2015 study of 976 women histologically or clinically designated as having LS who had a one month minimum follow-up were selected. The median age at diagnosis was 60 (8-91) years. The median follow-up was 211-339 months. 34 patients developed neoplasms (incidence risk: 3.5%). The probability of neoplasia occurrence at 24, 60, 120, 180, 240, and 300 months was 1.2%, 3.0%, 7.1%, 11.0%, 21.6% and 36.8% respectively. The authors concluded that the higher probability of malignant transformation in the longer periods suggests careful and lifelong follow-up in all LS patients.68

VSSC in the setting of lichen sclerosus

Accumulating data give clues to the relationship of LS and cancer. As mentioned above, experts theorize that T-cell receptor gene rearrangement could explain the increased risk of malignant transformation in individuals with LS.69 The monoclonal origin of LS suggests that clonal expansion may occur prior to epithelial atypia.70 Genetic and tumor marker alterations precede morphological atypia: markers of neoplasia– increased growth fraction, increased apoptosis– and alterations in the expression of p53 and its regulator have been linked with histologic progression from LS to vulvar cancer.71 A high degree of chromosome 17 aneuploidy affecting the p53 gene is found in LS adjacent to cancer.72 Allelic imbalances have been demonstrated in 43% of vulvar LS biopsies.73 And, changes in cell cycle proteins have been linked to the progression of lichen sclerosus to vulvar cancer.74

Psychosexual effects

LS may have a profound effect on women who may feel mutilated and less feminine. Scarring may lead to dyspareunia as well as sexual dysfunction.75 Validation of their concerns with proper clinical treatment can make a huge difference in outlook; emotional support and sexual counseling from a professional may be necessary. Support from other women can be invaluable.

Pregnancy

LS may present for the first time during pregnancy.76 The incidence of LS in pregnancy is unknown, and the effect of pregnancy on existing LS is not well studied. Women have reported improvement as well as worsening. 77 Mode of delivery is also not well studied. We do not recommend routine Cesarean section delivery if LS is well controlled and the vulvar epithelium is supple, elastic, and not inflamed.78 We do suggest Cesarean delivery for significant adhesions and inflamed skin with the opinion that obstetrical laceration in severely affected epithelium will have prolonged, possibly on-going morbidity.

For treatment in pregnancy:79

• Limited amounts of potent topical steroids are safe to use while pregnant or breast-feeding.

• Topical calcineurin inhibitors are contraindicated while pregnant or breast-feeding.

• Retinoids are absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy and for at least 2 years before conception. They should be used with caution in females of child-bearing age.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made based on the clinical pattern and histopathology.

Note: The clinical features are lost in the glare of over-bright lighting.

Pathology/Laboratory Findings

Contrary to many references in texts and atlases, in the early stages of LS both the clinical appearance and the histologic picture from biopsy may be difficult to interpret.80 Features may be similar to psoriasis or lichen planus: irregular acanthosis, mild hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, mild lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with lymphocyte tagging and dilated blood vessels immediately under the basement membrane, focal basement membrane thickening, luminal hyperkeratosis of adnexal structures, submucosal edema and homogenization, lymphocyte exocytosis.81 Only later in the disease may the pathogonomic findings of thinned epidermis with hyperkeratosis, a wide band of homogenized collagen beneath the dermo-epidermal junction, and a lymphocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized area be apparent.82 If LS has been present for a long period of time (especially since childhood), characteristic histological findings may be absent.83

Therefore, considerable clinical judgment combined with biopsy findings must be united for diagnosis. Biopsy may not be helpful if a potent topical steroid has been used within the last two to four weeks since hyalinization of lichen sclerosus is lost.84 85 A nonspecific biopsy does not rule out lichen sclerosus, although classic histologic findings confirm the diagnosis.86

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes inflammatory disease (vitiligo, morphea), erosive disease (lichen planus, cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris), infection (condyloma, herpes simplex virus), neoplasia (dVIN or HSIL, VSCC, extra-mammary Paget disease) and primary dermatoses (eczematous, allergic or irritant contact dermatitis), lichen simplex chronicus, and papulosquamous disease (seborrheic dermatitis, inverse psoriasis). Also in the differential are post-menopausal atrophy, and sexual abuse (in children).

Treatment/management

General treatments

- Education that this is a chronic disease that is managed, not cured. Safety of topical steroids must be discussed. (See below).

- Gentle cleansing with a very mild cleanser (Cetaphil cleanser).

- Avoidance of strong soaps and detergents.

- Use of ventilated cotton clothing.

- Avoidance of panty liners.

- Use of a mild lubricant for sexual intercourse.

- If very itchy, cool gel packs may be applied directly to the vulva for burning and itching (keep gel pack in refrigerator in a freezer bag with a zippered closure).

- Cool or luke warm sitz baths are soothing. The skin should be patted dry gently just before application of medication.

Specific treatments

Topical steroids

Topical super-potent steroids are the most effective,87 88 89 and are the treatment of choice.90 Randomized, controlled trials to support one ultrapotent steroid over another of for the length of treatment are lacking. But vulvar LS is a chronic skin disorder, and we routinely advise maintenance therapy with superpotent steroid ointment, as symptoms often recur in women who terminate therapy.91 Time to recurrence may vary from months to years. Over-use of superpotent and potent topical corticosteroids may induce atrophy, telangiectasia, and striae as early as two to three weeks following daily application; however, long-term follow-up of LS patients has not generally demonstrated these steroid-induced changes since the modified mucous membranes of the labia and clitoris are relatively resistant to the side effects of topical corticosteroids.92 93

Treatment needs to be individualized. We prescribe halobetasol or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice a day for 6 to 8 weeks in severe cases, once a day for 6 to 8 weeks in moderate cases and devise an individual maintenance program, varying from one to three times weekly. Other super potent topical steroids are betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% in augmented vehicle, mometasone furoate 0.1%, and diflorasone 0.05%.94 A 15 to 30 gram tube of ointment should last six months for initial treatment. Note: Ultra-potent steroids in the anal area are to be used with caution. For severe involvement, they can be used with proper local care (see general care above) for two weeks only. After this, a lower potency steroid such as desonide is used.

Some patients prefer ointments and others prefer creams but, in general, corticosteroid creams should be avoided because they contain irritants not found in ointments. In children, use mid- to high-potency steroid ointment. Oral glucocorticoids are effective but usually not indicated, given the risk of systemic side effects and the high efficacy of topical steroids. With proper treatment, the response of lichen sclerosus is usually dramatic. Maintenance topical therapy is long-term. Overuse and thinning of the skin must be avoided by showing the patient exactly where to put the ointment and how little is required (a dot 3 mm wide.)

The clinician expects that symptoms will come under control. Fissures and erosions will clear. Plaques will disappear. Purpura usually goes. Whitening may regress but it may remain and its resolution is not a treatment goal. Loss of architecture, that is, reabsorption of labia minora, fusion of prepuce over clitoris, or anterior and posterior synechiae, does not regress. Occasionally the hood of the clitoris becomes “unstuck” if it is mildly adherent.

If the risk of secondary candidiasis exists, topical Nystatin ointment or ketoconazole cream may be used over the steroid or weekly fluconazole 150 mg orally may be given.

If the patient is unwilling to use maintenance therapy, then we examine her every three to six months because asymptomatic recurrence resulting in scarring and loss of architecture can occur over a relatively short period of time. Some patients will achieve long-term remission without maintenance therapy, but it is impossible to predict who these patients are.

Other topical treatments

Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus appear to have some efficacy for vulvar LS, and may be useful as alternative treatment options. In a 12-week randomized trial of 38 patients with vulvar LS that compared pimecrolimus 1% cream to clobetasol 0.05% cream, both agents significantly reduced patient symptoms and improved histopathologic inflammation. 95 The degree of improvement in histopathologic inflammation with clobetasol was superior, supporting the status of superpotent topical corticosteroids as the preferred choice for initial therapy. These same authors did consider pimecrolimus safe.96

Additional support for the utility of topical calcineurin inhibitors comes from uncontrolled studies and case reports. Patients with vulvar LS, including some with topical corticosteroid-refractory disease, have exhibited improvement with pimecrolimus cream97 or tacrolimus ointment.98 99

Tacrolimus burns on application, and is often discontinued by patients for this reason. Although the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a “black box” warning for topical calcineurin inhibitors due to concern regarding an elevated risk for internal malignancy, a definitive relationship between these agents and internal malignancy has not been established. The impact of topical calcineurin inhibitor therapy on risk for vulvar SCC in patients with vulvar LS is unknown.

Topical oxatomide may help relieve pruritus through its antihistamine effects, but the course of disease is not affected.100

Intralesional steroids

For major itching and lichenification unresponsive to topical steroids, use intralesional triamcinolone (Kenalog-10) diluted, 1 ml of triamcinolone with 2 ml saline. Use EMLA anesthetic cream under plastic wrap for 20 minutes minimum to reduce the discomfort from the injections. Repeat the injections monthly for a total of four months, depending on the response. Patients need education that they are temporarily immunosuppressed, may experience slight increase or decrease in mood temporarily, may have elevated blood sugar for a few days, or may experience transient vaginal bleeding. This is an area of caution: Intralesional Kenalog is used in whitened plaques of lichen sclerosus that have not responded to steroids, but only after biopsy (even if repeat biopsy) to rule out squamous cell carcinoma.

Other drugs:

There are no well-studied therapies in women who fail to respond to corticosteroids. Given the high therapeutic efficacy of these agents, we investigate causes of steroid failure in women who have persistent symptoms before resorting to a trial of an alternative drug. (Persistent symptoms below).

Estrogen

Topical estrogen is valuable in the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and maintenance of epithelial integrity, yielding elastic and supple tissue, but has no role in the treatment of the intense inflammation of lichen sclerosus. Individual decisions need to be made about the use of vaginal estrogen in postmenopausal women with LS.

Progesterone and testosterone:

Small randomized trials have generally shown that progesterone and testosterone creams are less effective than clobetasol.101 Testosterone was associated with more side effects and less histological improvement than clobetasol102 and testosterone maintenance therapy worsened symptoms after initial clobetasol therapy.103 Placebo controlled trials of testosterone cream have reported conflicting results regarding efficacy.104 105 We do not prescribe these hormones for LS treatment.

Retinoids:

Retinoids may reduce connective tissue degeneration in LS.106 In a single randomized trial, treatment with oral acitretin (20 to 30 mg per day for 16 weeks) was effective.107 Doses of 8 to 30 mg daily for four months have been used. In an observational series, topical use of tretinoin improved the symptoms, gross appearance, and histopathologic features of LS with minimal side effects.108 However, side effects with the use of these agents include cheilitis, xerosis, teratogenicity, elevated liver enzymes, hypertriglyceridemia, abdominal pain, and alopecia. If a trial of retinoids is being considered, Consultation with or referral to a dermatologist is recommended before initiating therapy.109

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine has been used in only 10 patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus.110 111 Of these, three had significant improvement, five had some response, and two had no response. Cyclosporine is not recommended.112

Other therapy:

Laser: Support for the use of laser in LS treatment is lacking evidence and the long term possible adverse effects are also unknown.113

A trial of photodynamic therapy (PDT) with 20% 5-aminolevulinic acid caused significant burning.114 Although itching improved in 8 of 12 women, the course of the disease was not changed. In a later study, PDT was reportedly very effective in 100 patients who had partial or full remission of clinical objective signs and subjective symptoms.115

The best data are available for UVA1 of all the UV treatment modalities. Although this may be tried if all other treatments have failed, there have been documented development of genital cancers after PUVA and UVB.116 117

Autologous or (usually only in research settings) homologous platelet rich plasma (PRP) is a “hemoderivative rich in growth factors and cytokines, which is hypothesized to stimulate tissue regeneration and repair, making it a potential candidate for mitigating the symptoms and structural changes associated with LS.”118 119 Proponents consider it safe because the patient’s own blood products are used.

The use of adipose derived stem cells (ADSC) has also been described as a treatment for regeneration of tissue.120 121 Both of these techniques, used in sports medicine and other types of dermatological care, are sometimes used when traditional frontline therapies do not work, but require further studies. There are not enough valid data to support the use of these two modalities.122

Biologics have been used with one positive report of success with intralesional injection of adalimumab.123 On the other hand, lichen sclerosus has developed in a patient receiving imatinab for leukemia.124

Surgery

There is a 50% recurrence rate in patients who have been treated with surgery, even with full thickness skin grafts,125 since lichen sclerosus can also develop in grafted tissue.126 Laser surgery is not a common treatment for LS also because of recurrences.127 For the same reason, cryosurgery has not gained wide acceptance.128

Surgical intervention in lichen sclerosus is indicated only for the post-inflammatory sequelae of the disease, 129 including introital stenosis, fourchette adhesions, adhesions of the labia minora, and clitoral adhesions.

For introital narrowing, a vulvoperineoplasty (modified Fenton’s procedure) is indicated to remove the adhesions and construct a new introitus. The scarred area is excised; then a wide dissection and mobilization of the posterior wall of the vagina, reduction of the height of the perineal body, and advancement and eversion of the posterior vaginal wall are performed.130 Adhesions recur if only lysis or scar excision is done, without the vaginal advancement.

Synechiae at the fourchette often tear during sexual intercourse or with vaginal examination. They are a source of dyspareunia (as well as frustration) as they heal only to tear again. Median perineotomy (Fenton’s procedure) includes incising the adhesion, perineal skin, vestibular mucous membrane and the summit of the perineal body. The mucosal edges are undermined and sutured transversely with interrupted sutures.131

Labial adhesions may compromise the introitus or urethra.

They may be divided with cold knife or carbon dioxide laser. Refusion is a constant challenge. Essential management includes on-going control of LS with steroids. In addition, we have had success with motivated patients by instructing them to apply a barrier of petrolatum three times daily with an upward fingertip sweep to manually separate the labia on a frequent basis.

Clitoral adhesions from fusion of the prepuce may be symptomless. Orgasm may still be full and satisfying. In some women, aesthetic considerations and/or the complaint of diminished intensity of orgasm may lead to efforts to free the scarred prepuce from the glans. Accumulation of smegma under the fused hood may result in a clitoral pseudocyst. The adhesions are carefully incised with cold knife or carbon dioxide laser. Prevention of recurrence of adhesion may be achieved by resection of a tricorn shaped piece of the clitoral hood, everting the free edge, or by excision of the clitoral hood (circumcision).132 In our experience women seldom consent to these procedures; we have had success with the combination of steroid management of LS and thrice daily application of petrolatum with gentle manual retraction of the hood.

Follow-up

Schedule follow-up appointments according to need, frequently at first, then every six to twelve months. Follow-up is more than ensuring symptoms control: it is also a cancer prevention exercise,133 and an effort to prevent further scarring in women. In one study of 46 women with pre-pubertal onset of lichen sclerosus, all patients achieved initial objective disease suppression with induction treatment using potent topical corticosteroids. Of patients compliant with treatment 93.9% had sustained complete disease remission with no scarring. Of the non-compliant patients, those applying intermittent or no long-term topical corticosteroids, 8% achieved complete control on maintenance treatment, 23% experienced disease progression during treatment, with three patients developing scarring during follow up.134

Persistent symptoms

Given the high efficacy of steroids, when the treatment “is not working,” it is important to make sure the patient is complying with the prescribed corticosteroid therapy and understands that lifelong surveillance and treatment is necessary. The condition can not be treated appropriately if only the symptoms are treated and treatment stops when symptoms do. Before considering alternatives or more aggressive treatment it is essential to consider a number of reasons for suboptimal treatment response.

Correct application of ointment: Make sure the patient is applying the steroid to the right place and in the right amount (a thin layer to the affected area) and frequency. Women often are unclear as to where to put the ointment unless they are shown repeatedly with a mirror. The elderly or infirm may not be able to apply the topical properly. If they use too much steroid, their symptoms may not abate. They are often afraid of applying ultrapotent topical steroids to the anogenital region, 135 because of inaccurate information and because of frightening package instructions on the insert with the topical steroid.

Secondary complicating conditions: Consider secondary complicating conditions including on-going burning, irritation, and pain from infection with bacterial cellulitis, vulvar candidiasis, or vaginal candidiasis.136 Obtain cultures to exclude superinfection by staphylococcus, streptococcus, or candida. We treat infected patients with appropriate antibiotics or antimycotic drugs.

Menopausal women may have symptoms related to atrophy, which will respond to topical estrogen cream.

Superimposed pain: A diagnosis of superimposed vulvar pain from a known disorder should be considered if pain persists despite resolution of pruritus and dermal changes.137 It is likely that this pain represents neuropathic pain, which is pain arising from abnormal neural activity secondary to disease, irritation, or injury of the nervous system that persists in the absence of ongoing disease or acute injury. (Vulvodynia section of Annotation K: Vulvar pain and provoked and unprovoked vulvodynia).

Irritant reaction: Contact irritation or allergy to the topical medication may be present. A topical steroid with a different base or consultation with an allergy specialist should be considered.

Very thickened areas may not respond to topical steroids, but may respond to intralesional injection; however, malignancy should be excluded by biopsy. We consider repeating the biopsy to confirm the diagnosis or exclude an alternative diagnosis, especially to exclude malignancy. We send the biopsy specimen to a dermatopathologist for review.

We try tacrolimus cream if the patient has fissuring that fails to respond to the measures described above. We prescribe a tiny amount of 0.03% cream twice daily for a month and then reevaluate. Application of a base of petrolatum ointment or clobetasol first may help to prevent burning. Burning often resolves after a week or two.

In cases of true treatment failure, we suggest consultation with a dermatologist who has expertise in management of vulvar disease.

PEARLS

- LS has multiple appearances, not just whitened skin. Early LS may be erythematous.

- LS does not always produce itching.

- LS is a chronic disease and requires chronic management. Use of topical steroids has been shown to be safe on the vulva since 1988.

- Clinical judgment is essential in diagnosis. Negative biopsy does not rule the disease out. Classical findings do confirm it. Often it is suspected and the patient must be followed.

- Biopsy will be non-specific if disease has been present for a long time or if a steroid has been used within the past two weeks.

- When symptoms do not respond, always consider malignancy.

References

- Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 May 13;113(19):337-43. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. PMID: 27232363; PMCID: PMC4904529.

- Van de Nieuwenhof HP, Meeuwis KA, Nieboer TE, Vergeer MC, Massuger LF, De Hullu JA. The effect of vulvar lichen sclerosus on quality of life and sexual functioning. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31(4):279–284. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2010.507890

- Kraus CN. Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(9):1088. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0359

- Das S, Tunuguntla HS. Balanitis xerotica obliterans-a review. World J Urol. 2000; 18:382.

- Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 May 13;113(19):337-43. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. PMID: 27232363; PMCID: PMC4904529.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St John’s Dermatol Soc. 1971; 57:9-30.

- Singh N, Ghatage P. Etiology, clinical features, and diagnosis of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a scoping review. Obstet Gynecol Int. (2020) 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2020/7480754

- Smith SD, Fischer G. Childhood onset vulvar lichen sclerosus does not resolve at puberty: a prospective case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec; 26(6): 725-9

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H, Bieber K, Thaçi D, Ludwig RJ. Lichen sclerosus: The 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 16;10:1106318. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318. PMID: 36873861; PMCID: PMC9978401.

- Krapf JM, Smith AB, Cigna ST, Goldstein AT. Presenting symptoms and diagnosis of vulvar lichen sclerosus in premenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. (2022) 26:271–5. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000679

- Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, MacLean AB. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198:496.e1.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St John’s Dermatol Soc. 1971; 57:9-30.

- Fischer GO. The commonest causes of symptomatic vulvar disease: a dermatologist’s perspective. Australas J Dermatol. 1996; 37:12.

- Goldstein AT, Marinoff SC, Christopher K, Srodon M. Prevalence of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a general gynecology practice. J Reprod Med. 2005; 50:477.

- Leibovitz A, Kaplun V V, Saposhnicov N, Habot B. Vulvovaginal examinations in elderly nursing home women residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000; 31:1.

- van der Meijden, W.I., Boffa, M.J., ter Harmsel, B., Kirtschig, G., Lewis, F., Moyal-Barracco, M., Tiplica, G.-.-S. and Sherrard, J. (2022), 2021 European guideline for the management of vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 36: 952-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18102

- Scrimin F, Rustja S, Radillo O, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: an immunological study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 95:147.

- Regauer S. Immune dysregulation in lichen sclerosus. Eur J Cell Biol. 2005; 84:273.

- Cooper SM, Ali I, Baldo M, Wojnarowska F. The association of lichen sclerosus and erosive lichen planus of the vulva with autoimmune disease: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 2008; 144: 1432.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, Back MM. Lichen sclerosus et atophicus and autoimmunity-a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988; 118:41

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H, Bieber K, Thaçi D, Ludwig RJ. Lichen sclerosus: The 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 16;10:1106318. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318. PMID: 36873861; PMCID: PMC9978401.

- Higgins CA, Cruickshank ME. A population-based case-control study of aetiological factors associated with vulval lichen sclerosus. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:271–275

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. The development of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in monozygotic twin girls. Br J Dermatol. 1986; 140:377-379.

- Haefner, Hope K. MD; Welch, Kathryn C. MD; Rolston, Aimee M. MD, MS; Koeppe, Erika S. MS; Stoffel, Elena M. MD; Kiel, Mark J. MD, PhD; Berger, Mitchell B. MD, PhD. Genomic Profiling of Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus Patients Shows Possible Pathogenetic Disease Mechanisms. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 23(3):p 214-219, July 2019. | DOI: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000482

- van der Meijden, W.I., Boffa, M.J., ter Harmsel, B., Kirtschig, G., Lewis, F., Moyal-Barracco, M., Tiplica, G.-.-S. and Sherrard, J. (2022), 2021 European guideline for the management of vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 36: 952-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18102

- Marren P, Yell J, Charnock FM, et al. The association between lichen sclerosus and antigens of the HLA system. Br J Dermatol. 1995; 132:197-203.

- Liu GL, Cao FL, Zhao MY, Shi J, Liu SH. Associations between HLA-A\B\DRB1 polymorphisms and risks of vulvar lichen sclerosus or squamous cell hyperplasia of the vulva. Genet Mol Res. (2015) 14:15962–71. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.7.8, PMID

- Haefner, Hope K. MD; Welch, Kathryn C. MD; Rolston, Aimee M. MD, MS; Koeppe, Erika S. MS; Stoffel, Elena M. MD; Kiel, Mark J. MD, PhD; Berger, Mitchell B. MD, PhD. Genomic Profiling of Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus Patients Shows Possible Pathogenetic Disease Mechanisms. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 23(3):p 214-219, July 2019. | DOI: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000482

- Regauer S, Reich O. Beham-Schmid C. Monoclonal gamma T-cell receptor rearrangement in vulval lichen slcerosus and squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2002; 160:1035-1045.

- Tran DA, Tan X, Macri CJ, Goldstein AT, Fu SW. Lichen sclerosus: an autoimmunopathogenic and genomic enigma with emerging genetic and immune targets. Int J Biol Sci. (2019) 15:1429–39. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.34613, PMID

- Oyama N, Chan I, Neill SM, et al. autoantibodies to extracelllular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 2003; 362:118-123.

- Howard A, Dean D, Cooper S, et al. Circulating basement membrane zone antibodies are found in lichen sclerosus of the vulva. Australas J Dermatol 2004; 45(1):12-15.

- Sander CS, Ali I, Dean D, et al. Oxidative stress implicated in the pathogenesis of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2004; 151:627-635.

- Paulis G, Berardesca E. Lichen sclerosus: the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of the disease and its possible transformation into carcinoma. Res Rep Urol. 2019 Aug 20;11:223-232. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S205184. PMID: 31687365; PMCID: PMC6709801

- Weide B, Walz T, Garbe C. Is morphoea caused by Borrelia burgdorferi? A review. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 142:636.

- Yesudian PD, Sugundran H, Bates CM, O’Mahony C. Lichen sclerosus. Int J STD AIDS. 2005; 16:465.

- Hodgins MB, Sppike RC, Mackie RM, et a.. An immunohistochemical evaluation of androgen, oestrogen, and progesterone receptors in the vulva and vagina. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998; 105:216-222.

- Clifton MM, Garner IB, Kohler S, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of androgen receptiors in genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus: evidence for loss of androgen receptors in lesional epidermis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 41:43-46.

- Gunthert AR, Faber M, Knappe G. Early onset vulvar LS in premenopausal women and oral contraceptives. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008; 137:56-60.

- Higgins CA, Cruickshank ME. A population-based case-control study of aetiological factors associated with vulval lichen sclerosus. J Obstet Gynaecol. (2012) 32:271–5. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.649320, PMID

- Günthert AR, Limacher A, Beltraminelli H, Krause E, Mueller MD, Trelle S, et al.. Efficacy of topical progesterone versus topical clobetasol propionate in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus – a double-blind randomized phase II pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2022) 272:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.03.020, PMID

- Zhao Y, Zhao S, Li H, Qin X, Wu X. Expression of galectin-7 in vulvar lichen sclerosus and its effect on dermal fibroblasts. Oncol Lett. (2018) 16:2559–64. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8897, PMID

- Fisher BK, Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders. St Louis, Mosby , 1998, p189

- Yesudian PD, Sugundran H, Bates CM, O’Mahony C. Lichen sclerosus. Int J STD AIDS. 2005; 16:465

- Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 May 13;113(19):337-43. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. PMID: 27232363; PMCID: PMC4904529.

- Neill SM, Tatnall FM, Cox NH. Guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 147:640-649.

- Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 May 13;113(19):337-43. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. PMID: 27232363; PMCID: PMC4904529.

- Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28:707-715.

- Edwards L and Lynch P. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual, third edition. Wolters Kluwer, 2018. p 130

- Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28:707-715.

- Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28:707-715.

- Edwards L and Lynch P. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual, third edition. Wolters Kluwer, 2018. p 130

- Lorenz B, Kaufman RH, Kutzner SK. Lichen sclerosus: therapy with clobetasol propionate. J Reprod Med. 1998; 9:790-4.

- Fisher BK, Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders. St Louis, Mosby , 1998, 189.

- Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 May 13;113(19):337-43. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. PMID: 27232363; PMCID: PMC4904529.

- Neill SM, Tatnall FM, Cox NH. Guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 147:640-649.

- Azevedo RS, Romanach MJ, de Almeida OP, et al. Lichen sclerosus of the oral mucosa: clinicopathological features of six cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 38:855-860.

- Cooper SM, Woknarowska F. Influence of treatment of erosive lichen planus of the vulva on its prognosis. Arch Dermatol. 2006; 142:289-294.

- Derrick EK, Ridley CM, Kobza-Black A, et al. A clinical study of 23 cases of female anogenital carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 143:1217-1223.

- De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H, Bieber K, Thaçi D, Ludwig RJ. Lichen sclerosus: The 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Feb 16;10:1106318. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318. PMID: 36873861; PMCID: PMC9978401.

- Corazza M, Schettini N, Zedde P, Borghi A. Vulvar lichen sclerosus from pathophysiology to therapeutic approaches: evidence and prospects. Biomedicine. (2021) 9:950. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9080950

- Haefner HK, Tate JE, McLachlin CM, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: age, morphological phenotype, papillomavirus DNA, and coexisting invasive carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1995; 26:147-154.

- Allbritton J. Vulvar neoplasms, benign and malignant. Obstet Gynecol Clinics 2017; 44:3: 339-52.

- Griesinger LM, Walline H, Wang GY, Lorenzatti Hiles G, Welch KC, Haefner HK, Lieberman RW, Skala SL. Expanding the Morphologic, Immunohistochemical, and HPV Genotypic Features of High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions of the Vulva With Morphology Mimicking Differentiated Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia and/or Lichen Sclerosus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2021 May 1;40(3):205-213. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000708. PMID: 32925443; PMCID: PMC7960553.

- Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of vulval lichen sclerosus in adult women. Austral NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 50:148-52

- Renaud-Vilmer C. Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: effect of long-term topical application of a potent steroid on the course of the disease. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140(6):709-12

- Cooper SM, Gao X-H, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus influence its prognosis? Arch Dermal 2004; 140(6):702-6.

- Radici G, Preti M, Ghiringhello B, DiPumpo O, Previtera S, Micheletti L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and malignant transformation: a longitudinal retrospective study. Presented at the XXIII World congress of the International society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease, July 27-29, 2015, New York University, New York City, NY.

- Regauer S, Reich O. Beham-Schmid C. Monoclonal gamma T-cell receptor rearrangement in vulval lichen sclerosus and squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2002; 160:1035-1045.

- Tate JE, Mutter GL, Boynton KA, et al. Monoclonal origin of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and some vulvar hyperplasias. Am J Pathol. 1997; 150:315-322.

- Carlson JA, Amin S, Malfetano J, et al. Concordant p53 and mdm-2 protein expression in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma and adjacent lichen sclerosus. Appl Immuno Histochem Mol Morphol 2001; 9:150-163.

- Carlson JA, Healy K, Tran TA, et al. Chromosome 17 aneusomy detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization in vulvar squamous cell carcinomas and synchronous vulvar skin. Am J Pathol. 2000; 157:973-983.

- Pinto AP, Lin MC, Sheets EE, et al. Allelic imbalance in lichen sclerosus, hyperplasia and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol. 2000; 77:171-176.

- Neill SM, Tatnall FM, Cox NH. Guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 147:640-649

- Dalziel KL. Effect of lichen sclerosus on sexual function and parutition. J Reprod Med. 1995; 40:351-354.

- Haefner HK, Pearlman MD, Barclay ML, et al. Lichen sclerosus in pregnancy: presentation of two cases. J Lower Genital Tract Dis. 1999; 3:260-3.

- Dalziel KL. Effect of lichen sclerosus on sexual function and parturition. J Reprod Med. 1995; 40:351-354.

- Trokoudes D, Lewis FM. Lichen sclerosus – the course during pregnancy

and effect on delivery. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: e466–e468. - van der Meijden WI, Boffa MJ, Ter Harmsel B, Kirtschig G, Lewis F, Moyal-Barracco M, Tiplica GS, Sherrard J. 2021 European guideline for the management of vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 Jul;36(7):952-972. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18102. Epub 2022 Apr 12. PMID: 35411963.

- Regauer S. Liegl B, Reich O. Early vulvar lichen sclerosus; a histopathological challenge. Histopathology. 2005; 47:340-347

- Regauer S. Liegl B, Reich O. Early vulvar lichen sclerosus; a histopathological challenge. Histopathology. 2005; 47:340-347.

- Hewitt J. Histologic criteria for lichen sclerosus of the vulva. J Reprod Med. 1986; 31:781-787.

- Margesson, LJ. Lichen sclerosus: Treatment and prognosis. Post-graduate course, International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease, Sante Fe, NM, October, 1999.

- Neill SM. White lesions. In: Edwards L, Lynch PJ, eds. Genital Dermatology Atlas, 2nd edition. Philadelphia, Wolters Kluwer, 2011, 184.

- Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 May 13;113(19):337-43. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0337. PMID: 27232363; PMCID: PMC4904529

- Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28:707-715.

- Dalziel KL, Wojnarowska F: Long-term control of vulval lichen sclerosus after treatment with a potent topical steroid cream, J Reprod Med. 1993; 38(1): 25-27.

- Neill SM, Lewis FM, Taatnall FM, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus 2010. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 163:672.

- Edwards L and Lynch P. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual, third edition. Wolters Kluwer, 2018. 135

- van der Meijden, W.I., Boffa, M.J., ter Harmsel, B., Kirtschig, G., Lewis, F., Moyal-Barracco, M., Tiplica, G.-.-S. and Sherrard, J. (2022), 2021 European guideline for the management of vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 36: 952-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18102

- Renaud-Vilmer C, Cavelier-Balloy B, Porcher R, Dubertret L. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: effect of long-term topical application of a potent steroid on the course of the disease. Arch Dermatol. 2004; 140:709.

- Diakomanolis ES, Haidopoulos D, Syndos M, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus in postmenopausal women: a comparative study for treating advanced disease with clobetasol propionate 0.05%. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2002; 23:519.

- Moyal-Barracco M, Edwards L. Diagnosis and therapy of anogenital lichen planus. Dermatol Ther. 2004; 17:38.

- Edwards L and Lynch P. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual, third edition. Wolters Kluwer, 2018. 135

- Goldstein AT, Creasey A, Pfau R, et al. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of clobetasol versus pimecrolimus in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64:e99.

- Funaro D, Lovett A, Leroux N, Powell J. A double-blind, randomized prospective study evaluating topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% versus topical tacrolimus 0.1% in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 84–91.

- Nissi R, Eriksen H, Risteli J, Niemimaa M. Pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of lichen sclerosus. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007; 63:151.

- Luesley DM, Downey GP. Topical tacrolimus in the management of lichen sclerosus. BJOG. 2006; 113:832.

- Funaro D, Lovett A, Leroux N, Powell J. A double-blind, randomized

prospective study evaluating topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% versus topical tacrolimus 0.1% in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 84–91. - Origoni M, Ferrari D, Rossi M, et al. Topical oxatomide: an alternative approach for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet .1996; 55:259.

- Cattaneo A, De Marco A, Sonni L, et al. Clobetasol vs. testosterone in the treatment of lichen sclerosus of the vulvar region. Minerva Ginecol. 1992; 44:567.

- Cattaneo A, De Marco A, Sonni L, et al. Clobetasol vs. testosterone in the treatment of lichen sclerosus of the vulvar region. Minerva Ginecol. 1992; 44:567.

- Cattaneo A, Carli P, De Marco A, et al. Testosterone maintenance therapy. Effects on vulvar lichen sclerosus treated with clobetasol propionate. J Reprod Med. 1996; 41:99.

- Sideri M, Origoni M, Spinaci L, Ferrari A. Topical testosterone in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994; 46:53.

- Paslin D. Treatment of lichen sclerosus with topical dihydrotestosterone. Obstet Gynecol.1991; 78:1046.

- Niinimäki A, Kallioinen M, Oikarinen A. Etretinate reduces connective tissue degeneration in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989; 69:439.

- Bousema MT, Romppanen U, Geiger JM, et al. Acitretin in the treatment of severe lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the vulva: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994; 30:225.

- Virgili A, Corazza M, Bianchi A, et al. Open study of topical 0.025% tretinoin in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. One year of therapy. J Reprod Med. 1995; 40:614.

- Ormerod AD, Campalani E, Goodfield MJD. British Association of Der-matologists guidelines on the efficacy and use of acitretin in dermatology. Br J Dermatol 2010;162: 952–963.77

- Carli P, Cattaneo A, Taddei G, Giannotti B. Topical cyclosporine in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical findings. Arch Dermatol. 1992; 128:1279.

- Bulbul Baskan E, Turan H, Tunali S, et al. Open-label trial of cyclosporine for vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007; 57:276.

- van der Meijden, W.I., Boffa, M.J., ter Harmsel, B., Kirtschig, G., Lewis, F., Moyal-Barracco, M., Tiplica, G.-.-S. and Sherrard, J. (2022), 2021 European guideline for the management of vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 36: 952-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18102

- Tasker F, Kirby L, Grindlay DJC, Lewis F, Simpson RC. Laser therapy for genital lichen sclerosus: a systematic review of the current evidence base. Skin Health Dis 2021;1: e52. doi: 10.1002/ski2.52

- Hillemanns P, Untch M, Pröve F, et al. Photodynamic therapy of vulvar lichen sclerosus with 5-aminolevulinic acid. Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 93:71.

- Olejek A, Steplewska K, Gabriel A, Kozak-Damas I, Jarek A, Kellas-Sleczka S, Bydliński F, Sieroń-Stołtny K, Horak S, Chełmicki A, Sieroń A. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy in vulvar lichen sclerosus treatment based on immunohistochemical analysis of CD34, CD44, myelin basic protein, and Ki67 antibodies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010 Jul;20(5):879-887.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ferguson J, Ibbotson SH. UVA1 phototherapy forgenital lichen sclerosus.Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31: 343–347

- Terras S, Gambichler T, Moritz RKC, St€ucker M, Kreuter A. Ultraviolet-A1 phototherapy versus clobetasol propionate 0.05% in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus–a randomized controlled clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150: 621–627

- Paganelli A, Contu L, Condorelli A, Ficarelli E, Motolese A, Paganelli R, Motolese A. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and Adipose-Derived Stem Cell (ADSC) Therapy in the Treatment of Genital Lichen Sclerosus: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Nov 9;24(22):16107. doi: 10.3390/ijms242216107. PMID: 38003297; PMCID: PMC10671587.

- White C., Brahs A., Dorton D., Witfill K. Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Comprehensive Review of Emerging Applications in Medical and Aesthetic Dermatology. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2021;14:44–57.

- Casabona F, Priano V. et al. New surgical approach to lichen sclerosus of the vulva: the role of adipose-derived mesenchymal cells and platelet-rich plasma in tissue regeneration. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 128(4):201e-211e

- Paganelli A, Contu L, Condorelli A, Ficarelli E, Motolese A, Paganelli R, Motolese A. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and Adipose-Derived Stem Cell (ADSC) Therapy in the Treatment of Genital Lichen Sclerosus: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Nov 9;24(22):16107. doi: 10.3390/ijms242216107. PMID: 38003297; PMCID: PMC10671587.

- shtiaghi P, Sadownik LA. Fact or fiction? Adipose-derived stem cellsand platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus.J Low Genit Tract Dis2019;23:65–70

- Feig J, Gribetz M, Leewohl M. Chronic lichen sclerosus successfully treated with intralesional adalimumab. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174:687-89

- Skupsky H, Abuav R, et al. Development of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus while receiving a therapeutic dose of imatinab mesylate for chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Cutan Pathol 2010; 37(8):877-80

- Smith YR, Haefner HK. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004; 5(2):105-125.

- di Paola GR, Rueda-Leverone NG, Belardi MG. Lichen sclerosus of the vulva recurrent after myocutaneous graft. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1982 Oct;27(10):666-668.

- Smith YR, Haefner HK. Vulvar lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004; 5(2):105-125

- Wakelin SH, Marren P. Lichen sclerosus in women. Clin Dermatol. 1997; 15:155-69.

- Paniel BJ, Rouzier R. Surgical procedures in benign vulval disease. In: Neill S, Lewis F, eds. Ridley’s The Vulva.Oxford, England Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, 233.

- Paniel BJ, Rouzier R. Surgical procedures in benign vulval disease. In: Neill S, Lewis F, eds. Ridley’s The Vulva.Oxford, England Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, 233.

- Paniel BJ, Rouzier R. Surgical procedures in benign vulval disease. In: Neill S, Lewis F, eds. Ridley’s The Vulva.Oxford, England Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, 233.

- Paniel BJ, Rouzier R. Surgical procedures in benign vulval disease. In: Neill S, Lewis F, eds. Ridley’s The Vulva.Oxford, England Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, 233.

- Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of vulval lichen sclerosus in adult women. Austral NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010; 50:148-52.

- Lee A, Ellis E, Fischer G. Pre-pubertal onset of vulvar lichen sclerosus: the importance of maintenance therapy in long-term outcomes. Presented at the XXIII World congress of the International society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease, July 27-29, 2015, New York University, New York City, NY.

- Neill SM, Tatnall FM, Cox NH. Guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 147:640-649

- Nyirjesy P. Lichen Sclerosus and Other Conditions Mimicking Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2002; 4:520.

- Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28:707-715.