Introduction

Trauma to the vulva can come about a number of different ways: through accident, through tattooing or body piercing and associated complications, through foreign bodies being inserted into the vagina, through obstetrical or gynecological surgery-related procedures, through radiotherapy of malignancies, through self-mutilation, through sexual trauma, and through female genital cutting.

Accidental Trauma

Accidental trauma to the vulvar area is uncommon.1 The vulva can be injured only when the thighs are open or are flexed on the trunk.

Vulvar trauma is most common in children. Risks include falling astride a bicycle bar, fence, or barrier with blunt or sharp edges; being kicked; falling violently while water skiing or surf boarding; becoming impaled with a stake, etc.

Bruise

The most common physical finding is bruising, especially where there are torn muscles, and it is most noticeable over bony attachments.

The vulva itself can form one large hematoma, and a thrombosis involving the perineum may generate intense pain.

Lacerations

The extent of lacerations depends entirely on the force involved in the injury and the sharpness of the offending object. If the penetrating wound is deep, it can involve the vagina, urinary tract, rectum, or even the abdomen.

Burns

Burns can result from any one of several sources of heat—hot water,

cooking fluids, and most commonly, fire. The degree of injury often depends on the type of clothing being worn by the victim.

Self-inflicted trauma

Tattoos

A tattoo results from the introduction of exogenous pigments into the skin.2 Decorative tattooing has been practiced since ancient times. It has become much more popular in the last decade in both sexes. Although still rare, it is becoming more common in the genital area.

- Technique and Materials

Tattoos may be administered by a professional or an amateur. The professional uses an electric motor-driven, multi-headed needle for introducing the pigment particles into the dermis, whereas the amateur usually uses any pointed object with ink or soot. The most common pigment colors are black (carbon), red (cinnabar), green (chromic oxide), yellow (cadmium sulfide), and blue (cobaltous aluminate). - Complications

Complications include an introduction of infections (e.g., pyoderma, hepatitis, HIV ) and allergic reactions to the pigment (e.g., chromate). Dissatisfaction and embarrassment may also be problems and are further complicated by the difficult and sometimes costly removal. A Q-switched ruby laser can be used to remove blue and black ink. Other lasers are used for other colors with variable success. It may not be possible to completely destroy a green, yellow, or amateur tattoo without scarring.

Body Piercing

Like tattoos, body rings are also very popular these days.3 The genital area is the third most common area after the head (ears, nose, and lips) and the umbilical area.

Body piercing involves passing a sharp instrument through the skin. This is followed by the placement of a ring or stud through the opening. The jewelry is left in place and the wound heals, leaving a permanent sinus.

- Complications:

This procedure may result in a local inoculated infection (as in tattoos), contact dermatitis (usually to nickel), or keloidal scarring. Rings may be traumatically pulled and the sinus partially or completely torn, with pain and scarring.

Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies inserted into the vagina more commonly cause troubles in children than in adults.4 These children develop a chronic vaginal discharge and an irritant dermatitis in the vulva. At times, the whole vulvovaginal area may be swollen. The child may complain of itching, burning, or soreness. One of the most common foreign bodies is toilet tissue, but toys, peanuts and other small items may be found.

In adults, foreign bodies such as forgotten tampons can cause copious malodorous discharge and an irritated vulvovaginitis with itching and burning. Other foreign bodies, medical (e.g. pessary) or non-medical (e.g. molded phallus) may cause vulvovaginitis and nonspecific vulvar problems.

Self-mutilation

Psychiatrically ill patients and patients with mental handicaps may uncommonly mutilate their own genitalia.5 This may occur during masturbation, as the result of a delusion, or as an act of self-destruction. The causes of trauma vary. Recognizing the causes may be difficult. Chronic excoriation and picking are fairly easily recognized. (prurigo nodularis in Atlas). Cigarette burns may be difficult to diagnose.

It may take strong suspicion by the physician and very careful questioning to diagnose the cause of problems in the patient who appears normal. These individuals often present as honest and straightforward. Only with time do the underlying psychologic problems start to appear. Treatment requires a non-confrontational approach and a lot of patience.

The synonym for self-mutilation is factitial vulvitis. The classification of such destruction includes the following:

- Secondary trauma inflicted on underlying dermatoses (e.g. psoriasis, lichen sclerosus).

- Lesions in individuals who neurotically manipulate, overtreat, or pick at minor, insignificant, or imagined vulvar lesions.

- Factitial ulcers resulting from self-mutilation by psychotic individuals.

Investigating a patient’s history may not be helpful. There may be no complaints, and the patient is often unable to explain the lesions. There may be major symptoms of incapacitating itch, crawling sensations, burning, etc. Other parts of the body may also be a problem. The patient usually denies a self-induced component. In factitial ulcers, the history may be very bizarre.

Medically induced trauma

Obstetric/surgical trauma

With precipitous delivery and/or a very large baby, stretching, bruising, or frank tearing of the vulva can occur, resulting in laceration and variably sized hematoma formation.6 Rarely, a perineal tear can extend anterior to the meatus or posterior to the rectum.

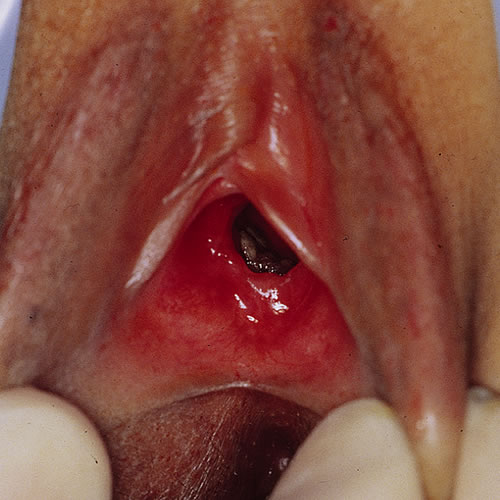

Obstetric trauma is frequent and involves vulvoperineal tears and genital thrombosis. Vulvar tears may be anterior around the meatus or clitoris and are usually unilateral with bleeding. The lateral tears in the labia minora are usually minor. Occasionally part of the labia minora can be torn away or perforated.

Perineal tears can be partial, complete, or complicated. Partial tears range from a simple split to a complete tear of the perineal body down to the anal sphincter. The complicated tear (third or fourth degree) involves the whole perineal body, anal sphincter, and the anterior wall of the rectum.

Gynecologic surgery may also produce significant hematoma formation.

Scarring can occur anywhere in the vulva following such surgery, particularly the extensive surgery needed for hidradenitis suppurativa, squamous cell carcinoma, Paget disease, or melanoma. The resulting scarring can result in significant vulvar or vaginal stenosis.

Vulvectomy may be necessary for some of these patients, and there may be resulting numbness, urinary difficulties, and sexual dysfunction. These patients may be depressed, with loss of self confidence.

Radiodermatitis

Radiotherapy of malignant vulvar or pelvic tumors usually results in a degree of secondary cutaneous reaction, either acutely or chronically.

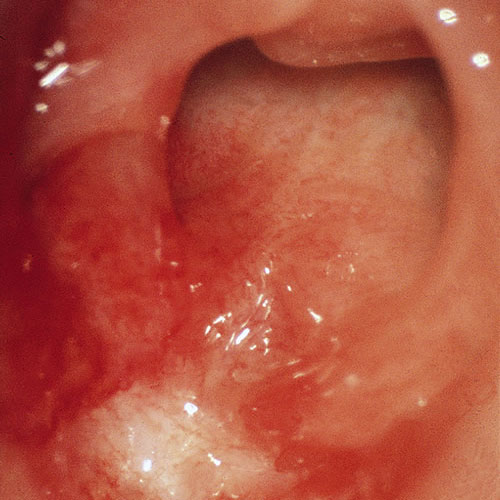

Acute radiation vulvitis occurs at the end of the course of irradiation. Clinically, there is edema with violaceous discoloration, pain, burning, and occasionally, frank bullae and necrosis.

In late radiodermatitis, the changes are seen years after radiation therapy. The vulvar skin is thinned, whitish, scarred, and shows extensive telangiectasia.

This is relatively asymptomatic.

Other-induced trauma

Sexual assault/rape

The definition of rape varies throughout the world. For a thorough discussion about sexual assault in the United States and evaluation of female patients, please see the attached article by expert Judith A. Linden, MD: Care of the Adult Patient after Sexual Assault, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 2011; 365: 834-841, used with kind permission of the author.

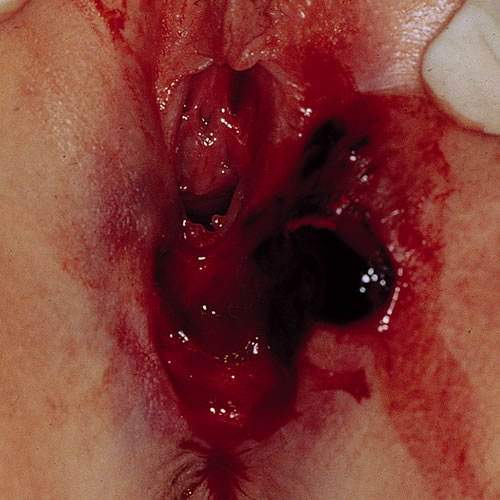

The degree of vulvovaginal injury is variable in cases of sexual assault.7 Lacerations are common and very extensive in the young child or virgin. Considerable hemorrhage and hematoma formation can also occur.

The laceration can involve the hymenal ring and extend into the vagina with profuse bleeding. In a child, the lacerations can be much deeper, even into the rectum and bladder. Other types of injury may be present on the body and include scratches, abrasions, bruises, and hematoma depending on the degree of force.

Treatment

Treatment is best provided by a specially trained team involving gynecology and emergency medicine with psychologic support. Major attention has to be given not only to the physical wounds but also to the psychologic ones. In each jurisdiction, there are medicolegal issues that must be addressed. Please see Dr Linden’s article regarding this. (LINK to PDF)

Sexual abuse in children

Child sexual abuse refers to the involvement of a dependent, developmentally immature child or adolescent in sexual activities by another (usually older) person for that person’s own sexual stimulation or for gratification of others, as in pornography or prostitution. Activities involve oral-genital, genital-genital, and anal-genital contact, and include exhibitionism, sexualized kissing, fondling, masturbation, and digital or object penetration of the vagina and anus. In the United States in 2005-2006, there were 135,300 reported cases of child sexual abuse.8 However, 70% of sexually abused children do not tell anyone about the abuse. As many as one in three girls and one in seven boys will be sexually abused at some point in their childhood.9 Child sexual abuse occurs in all racial, religious, ethnic, and age groups and at all socioeconomic levels. In as many as 93% of child sexual abuse cases, the child knows the person that commits the abuse.10 Most abusers are acquaintances, but as many as 47% are family or extended family members.11

Sexual abuse is a complex medical and social problem. It involves the abuse of power and the betrayal of the child’s trust by another (usually older) person. Major long-term problems occur with sexually abused children and their families. Being aware that sexual abuse is such a common problem should alert the clinician to consider it when examining children who present with an infection (condyloma acuminata, herpes simplex, gonorrhea, and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)), or with trauma that includes scratches, bruising, or hematoma, lacerations or fissures, scars, and gaping of the anus or introitus.

The reader is directed to an excellent article by Margaret R Hammerschlag and Christina D. Guillén: Medical and Legal Implications of Testing for Sexually Transmitted Infections in Children. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 July; 23(3): 493-506. (LINK to PDF) for an in-depth discussion.

Obtaining an appropriate history requires interview techniques used by specially trained personnel. These children often have poor self-esteem. They may have withdrawn or be acting out. Sometimes, they are very anxious to please.

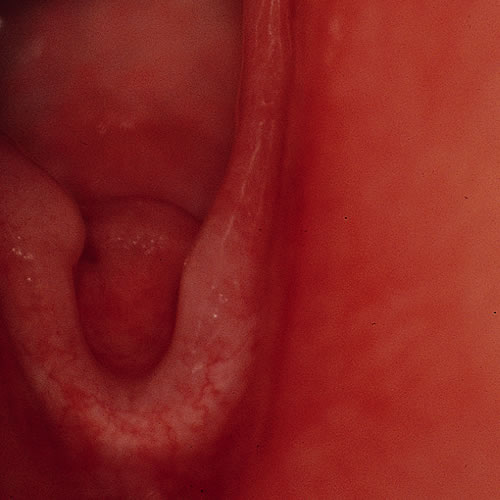

Physical examination often involves following special local protocols. Total physical examination is necessary, plus cultures for all of the STIs, where indicated. Understanding the normal anatomy is important. The hymen is usually annular or crescentic in children. A variety of notches and bumps are quite normal. Changes are usually chronic, showing healed transections of the hymen between the 4 and 8 o’clock positions and sometimes partial hymenal loss.

The majority of sexual abuse does not show changes of painful or forced trauma. In some cases, there may be abrasions, lacerations, or bruising, but the area heals very quickly. Any question of child sexual abuse must be reported to the proper authorities.

It is very important to realize that dermatoses such as lichen sclerosus can affect females of any age. Lichen sclerosus can present, in the child, as constipation or anal problems, or as bruising.

Scratches and odd scarring that might accompany LS can also be mistaken for signs of abuse.

Treatment of child sexual abuse is best handled by a specialized team.

References

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 115-116.

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 116-117.

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 117.

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 120.

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 123-124.

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 122.

- Fisher BK and Margesson LJ. Genital Skin Disorders: diagnosis and treatment.1998. Mosby, St Louis. 125.

- Sedlak, A.J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Petta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A., and Li, S. (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

- Briere, J., Eliot, D.M. Prevalence and Psychological Sequence of Self-Reported Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse in General Population. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003, 27; 10.

- Douglas, Emily and D. Finkelhor, Childhood sexual abuse fact sheet, http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/factsheet/pdf/childhoodSexualAbuseFactSheet.pdf, Crimes Against Children Research Center, May 2005

- Briere J, Eliot D.M. Prevalence and Psychological Sequence of Self-Reported Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse in General Population. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003. 27; 10.