Introduction

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is an uncommon, deep, soft tissue infection, usually caused by toxin-producing virulent bacteria that results in progressive destruction of the muscle fascia and overlying subcutaneous fat. Infection typically spreads along the muscle fascia due to its relatively poor blood supply; muscle tissue is frequently spared because of its generous blood supply.1 Originally called Fournier’s gangrene, in women NF is usually described as a fulminating infection of the inguinal region, lower abdominal wall, and perineum, along with the vulva. Shortly after the onset of the disease, patients become colonized with their own aerobic and anaerobic microflora from the gastrointestinal and/or urogenital tracts. Early diagnosis with aggressive multidisciplinary treatment is mandatory.

In 2010, clinical classification distinguished four NF types: Type I (70-80%, polymicrobial/synergistic), type II (20% of cases; usually monomicrobial), type III (gram-negative monomicrobial, including marine-related organisms) and type IV (fungal). 2

Currently, in 2022, classification is identified as follows:

-

Polymicrobial (type I) NF. Type I NF stems from polymicrobial infection identified via microbiological culture. This type of infection is caused by both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. The complex microbiological profile of offending organisms leads to gaseous infiltration of subcutaneous tissue similar to gas gangrene. Type I NF accounts for most reported cases of NF and is more prevalent in older adults with chronic diseases.

-

Monomicrobial (type II) NF is most commonly associated with Gram-positive organisms such as group A Streptococcus (GAS) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Endotoxins released by type II NF organisms are responsible for some clinical presentations, including toxic shock syndrome. Type II NF is not associated with a specific age group. Some patients do not have comorbidities or an obvious portal of entry that predisposes them to severe infection.3

Several other species of organisms have been implicated in NF, including Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Clostridium, Aeromonas, and Vibrio vulnificus. These organisms, while rare, are more virulent and produce more severe clinical manifestations. The identification of these microbes has led some experts to propose a third type classification of NF, but no consensus has been reached.4

The two forms of NF are also differentiated by the site of the infection. Necrotizing microbial infiltration into the submandibular space fascia leading to tissue damage is called Ludwig angina. An oropharyngeal infection leading to secondary septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein is termed Lemierre syndrome. Fournier gangrene, described as bacterial infiltration into the gastrointestinal or urethral mucosa, can progress rapidly into the perineal region. These alternate classifications and nomenclatures may not have significant impact on immediate clinical management of NF but are important nevertheless for epidemiologic purposes.5

In a 2017 study, a total of 230 patients were found to have necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs); 197 had intra-operative cultures, and 21 (10.7%) of these were positive for fungi. Fungal infection was more common in women, patients with higher body mass index (BMI), and patients who had had prior abdominal procedures. There were no significant differences in demographics, co-morbidities, or site of infection. The majority of patients (85.7%) had mixed bacterial and fungal infections; in the remaining patients, fungi were the only species isolated. Most fungal cultures were collected within 48 h of hospital admission, suggesting that the infections were not hospital acquired. Patients with positive fungal cultures required two more surgical interventions and had a three-fold greater mortality rate than patients without fungal infections.6

Epidemiology

Necrotizing fasciitis has a progressive and rapidly advancing clinical course. Although occurring in all age groups, NF is slightly more common in older age groups (>50years of age).7 The incidence of NF has been reported to be 0.3 to 15 cases per 100,000 population.8 9 There is a male to female ratio of 3:1 in all cases of NF. Diabetes is a common comorbidity. Though NF is rare, its mortality rate is high, ranging from 25 to 35%.11

Etiology

Idiopathic causes are seen very often in younger populations.12 The main sources of infection are elective skin operations, skin abscesses, and pressure sores. Frequent colorectal disease includes anorectal infections, ischiorectal abscesses, colon perforations, and some elective anorectal diagnostic procedures, e.g., rectal biopsy, anal dilatation, or hemorrhoidal banding. In women, Bartholin gland abscesses and vulval skin infections are the most common causes of NF.

Necrotizing fasciitis is characterized by widespread necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and fascia. Its rapid and destructive clinical course is assumed to be caused by polymicrobial symbiosis and synergy.13 As stated above, any aerobic and anaerobic pathogens may be involved, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Enterobacteriaciae, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella, but group A hemolytic streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus, alone or in synergism, are the initiating infecting bacteria.14 In most NF cases anaerobic bacteria are present, usually in combination with aerobic gram-negative organisms. They proliferate in an environment of local tissue hypoxia. Because of lower oxidation-reduction potential, they produce gases such as hydrogen, nitrogen, hydrogen sulfide and methane, which accumulate in soft tissue spaces because of reduced solubility in water.15

Symptoms and Clinical Findings

EARLY SYMPTOMS (usually within 24 hours):

1. Usually a minor trauma or other skin opening has occurred; (the wound does not necessarily appear infected).

2. Tenderness, erythema, and edema appear. The edema often extends beyond the erythema. The hallmark of vulvar necrotizing fasciitis is a woody induration extending onto the inner thighs.16

3. The pain is usually disproportionate to the initial appearance of the skin. Intense pain may ensue, but with tissue necrosis and destruction of cutaneous nerves, local pain progresses to anesthesia.17

4. Flu-like symptoms begin to occur, such as diarrhea, nausea, fever, confusion, dizziness, weakness, and general malaise

5. Intense thirst occurs as the body becomes dehydrated.

6. The combination of symptoms continues to cause significant distress disproportionate to the clinical appearance.

ADVANCED SYMPTOMS (usually within 3-4 days):

1. The area of the body experiencing pain begins to swell, and may show a purplish rash.

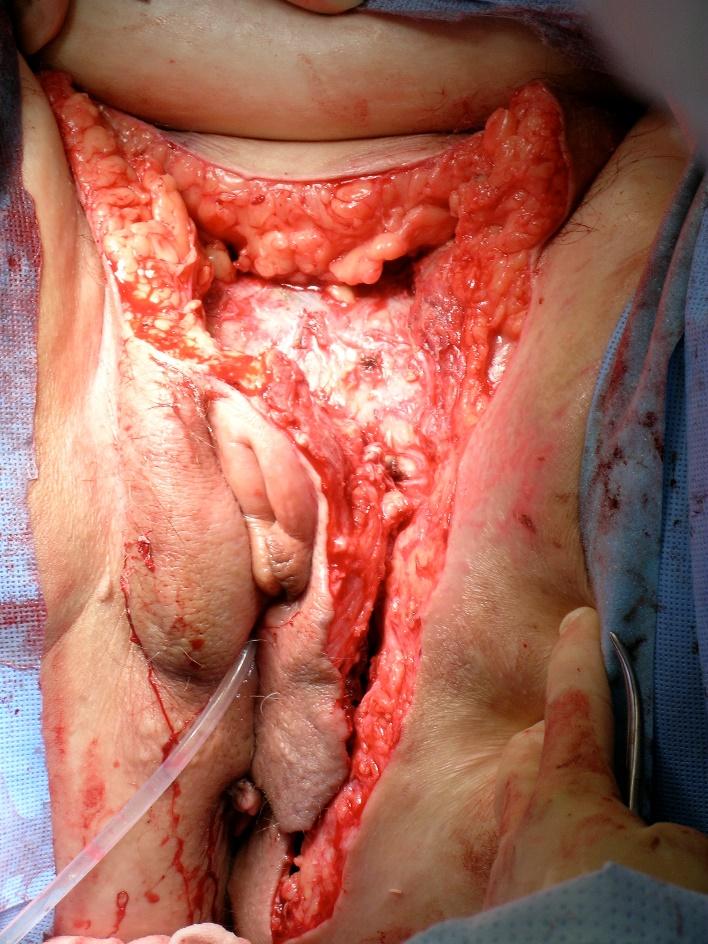

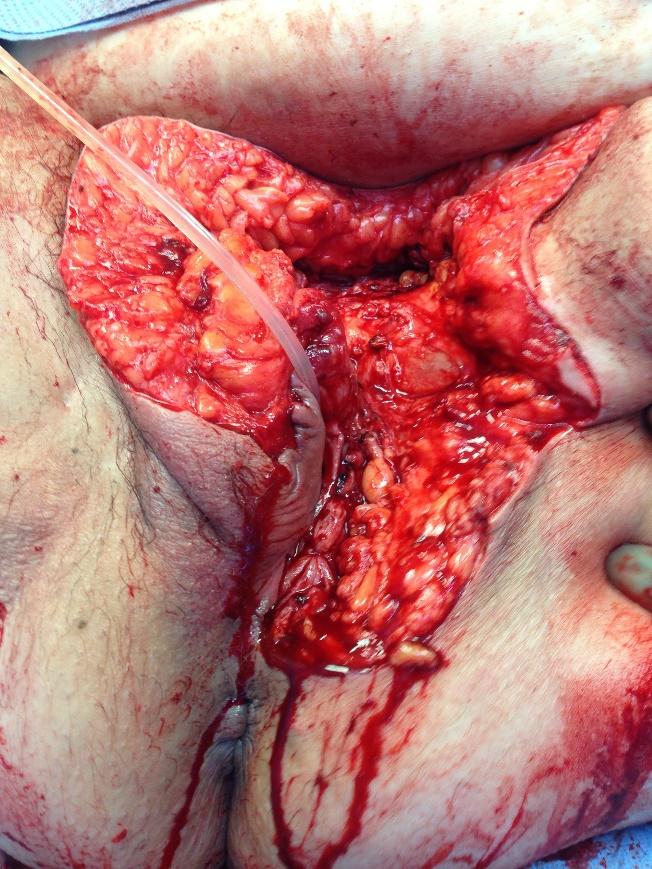

2. The area may show large, dark macules evolving to blisters filled with blackish fluid. Putrid discharge occurs.

3. The tissue may appear necrotic with a bluish, white, or dark, mottled, flaky appearance.

CRITICAL SYMPTOMS (usually within 4-5 days):

1. Blood pressure will drop severely

2. Toxic shock develops

Diagnosis

Early clinical findings of tenderness, edema, erythema, and pain suggest mild cellulitis. These signs and symptoms worsen as malaise, chills, fever, leukocytosis, then systemic toxicity develop. Rapidly progressive cellulitis with systemic findings and lack of classical marked tissue inflammatory signs associated with a paucity of early specific cutaneous findings should raise suspicion for NF.18

Another cardinal sign of NF is accumulation of gas in the soft tissue, seen on plain x-ray in half of all NF cases. Crepitation may be noted. Gas bubbles from the cutaneous spaces can be demonstrated with skin puncture using a large gauge needle.19

CT and MRI will give information about the nature and extent of the necrotizing infection.20

Pathology/laboratory findings

Key histopathological findings are microvascular thrombosis, secondary tissue necrosis, and abscess formation. Systemic vasculitis including the eyes, cutaneous sites, and genitals is reported.21

Lab studies should include a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lactate level, creatine kinase, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Confirmatory diagnosis of the causative bacteria is based upon a culture and Gram stain of specimens collected from deep tissue, or by positive blood cultures. Cultures collected from superficial sites may not have clinical value if the causative organism is within the deep tissue.22

Plain radiography has not been shown to provide adequate diagnostic accuracy and is not recommended as an initial or definitive imaging study for NF. Computed tomography (CT) and MRI may show edema extending along the fascial plane, although these findings may be absent in early stages of NF.23

Although MRI may provide superior results, CT is favored as the initial imaging choice because is generally more readily available for emergent imaging than MRI. However, surgical intervention should not be delayed in order to facilitate diagnostic imaging. Surgical exploration is the only way to establish the diagnosis of necrotizing infection.24

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include cellulitis, pyoderma, impetigo, erysipelas, mucositis, gas gangrene, and cutaneous anthrax.

Treatment/management

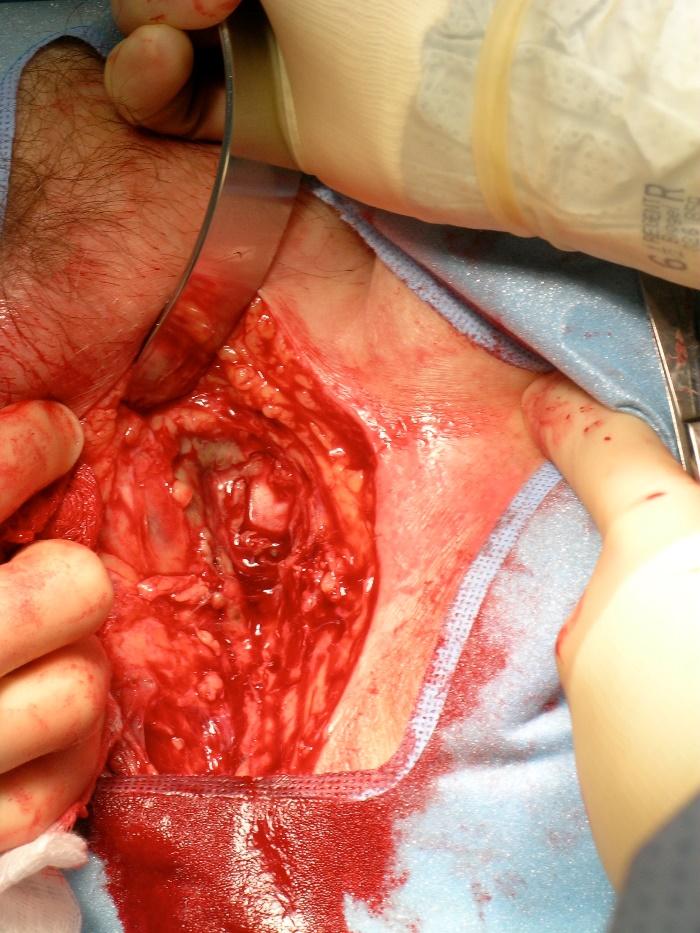

NF must be treated with a multidisciplinary team approach in the hospital. Resuscitation of a patient in shock, and initiation of broad spectrum antibiotics to cover polymicrobial infection are first steps. The most recent Infectious Disease Society of America guideline recommends either vancomycin or linezolid in combination with piperacillin-tazobactam, a carbapenem, or ceftriaxone-metronidazole. Clindamycin should also be included in empiric therapy due to its effect on toxins released by certain organisms, including S. aureus and GAS. Penicillin plus clindamycin is recommended to treat documented GAS necrotizing infections.25 Early comprehensive debridement in the operating room is essential to control infection and reduce mortality.26 Cultures and frozen sections should be obtained. Antibiotics are adjusted according to culture results. Repeated debridement every 24-48 hours is performed until the infection is controlled. Occasionally, large defects require skin grafts and/or myocutaneous or omental flaps.27

A hyperbaric oxygen chamber, if available, is sometimes used in certain cases involving anaerobic infection in the hemodynamically stable patient. The use of I.V. immunoglobulin G (IVIG) for management of NF remains controversial.28

References

- Stevens DL and Baddour, LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate 2022 www.uptodate.com

- Morgan MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotizing fasciitis: a multiparametric approach. J Hosp Infect. 2010; 75:249-257.

- Chen LL, Fasolka B, Treacy C. Necrotizing fasciitis: A comprehensive review. Nursing. 2020;50(9):34-40. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000694752.85118.62

- Chen LL, Fasolka B, Treacy C. Necrotizing fasciitis: A comprehensive review. Nursing. 2020;50(9):34-40. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000694752.85118.62

- Chen LL, Fasolka B, Treacy C. Necrotizing fasciitis: A comprehensive review. Nursing. 2020;50(9):34-40. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000694752.85118.62

- Horn CB, Wesp BM, Fiore NB, et al. Fungal Infections Increase the Mortality Rate Three-Fold in Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections. SOSurg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18(7):793. Epub 2017 Aug 29.

- Levine EG, Manders SM. Life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Dermatol. 2005; 23:144-147.

- Tang S, Ho PL, Tang VW, Fung KK. Necrotizing fasciitis of a limb. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001; 3(5):709-714.

- Stevens DL, Baddour LM. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. UpToDate. 2020. www.uptodate.com

- Wang J-M, Lim H-K. Necrotizing fasciitis: eight-year experience and literature review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18(2):137–143. Female sex, older age, delay to first debridement, disease due to group A streptococci, an elevated serum creatinine or lactic acid level, and a greater degree of organ dysfunction upon admission are all associated with higher mortality.10Millett C, Halpern A. Reboli A, Heymann W. Bacterial Diseases. Dermatology, edited by Jean Bolognia, Elsevvier Limited, 2018.

- Azize KIc, Yimaz Ali Klc. Fournier’s gangrene: etiology, treatment, and complications. Ann Plast Surg. 2001; 147(5):523-7.

- Levine EG, Manders SM. Life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis. Clin Dermatol. 2005; 23:144-147.

- Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concept and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009; 208(2):279-288.

- Marron CD. Superficial sepsis, cutaneous abscess and necrotizing fasciitis. Brooks A, Mahoney PF, Cotton BA, Tai Neds. Emergency Surgery, first ed. Oxford, England, Blackwell Publishing 2010, 115-123.

- Lazenby, GB, Thurman AR, Soper, DE. Vulvar Abscess. UpToDate, Inc. 2022.

- Roje Zd, Roje Z, Matic D, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: literature review of contemporary strategies for diagnosing and management with three case reports: torso, abdominal wall, upper and lower limbs. World J Emerg Surg. 2011; 6(46): provisional PDF prior to publication:10. 1186/1749-7922-6-46 http://www.wjes.org/content/6/1/46

- Marron CD. Superficial sepsis, cutaneous abscess and necrotizing fasciitis. Brooks A, Mahoney PF, Cotton BA, Tai Neds. Emergency Surgery, first ed. Oxford, England, Blackwell Publishing 2010, 115-123.

- Roje Zd, Roje Z, Matic D, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: literature review of contemporary strategies for diagnosing and management with three case reports: torso, abdominal wall, upper and lower limbs. World J Emerg Surg. 2011; 6(46): provisional PDF prior to publication:10. 1186/1749-7922-6-46 http://www.wjes.org/content/6/1/46

- Morgan MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotizing fasciitis: a multiparametric approach. J Hosp Infect. 2010; 75:249-257.

- Roje Zd, Roje Z, Matic D, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: literature review of contemporary strategies for diagnosing and management with three case reports: torso, abdominal wall, upper and lower limbs. World J Emerg Surg. 2011; 6(46): provisional PDF prior to publication:10. 1186/1749-7922-6-46 http://www.wjes.org/content/6/1/46

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

- Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2253–2265.

- Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Low Co. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85-a(8):1454-1460.

- Cabrera H, Skoczdopole L, Marini M, et al. Necrotizing gangrene of the genitalia and perineum. Int Soc Dermatol. 2002; 41:847-861

- Misiakos EP, Bagias G, et al. Current concepts in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014;1:36.