Annotation E: Detailed, systematic vulvar examination

Click here for Key Points to AnnotationThe detailed vulvar examination is the sine qua non for diagnosis, requiring total familiarity with normal vulvar anatomy (Annotation F: the vulvar architecture) and systematic, focused attention to the details of the twelve vulvar anatomical structures outlined below. From the history, you may have some clues as to where to look or what to look for, but women can rarely describe the location of their symptoms accurately in words alone.

The systematic vulvar examination prevents missing tender areas or overlooking subtle architectural changes or epithelial abnormalities. It helps to identify what is normal in the vulva, eliminating improbable diagnoses and limiting the differentials. Systematic exam familiarizes the clinician with “normal” so that “abnormal” is more likely to stand out and be identified. Unexpected vulvovaginal findings are also common (e.g. the woman complains of perineal itching but the clitoris is scarred), and more than one problem frequently occurs (e.g. she has lichen sclerosus and Candida).

Ultimately, in order to diagnose, the examiner needs to describe:

- the exact location of symptoms and/or tenderness, (Annotation I, Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test.)

- the appearance of the vulvar architecture (hypertrophy, atrophy, mass, absence) (Annotation F, The vulvar architecture)

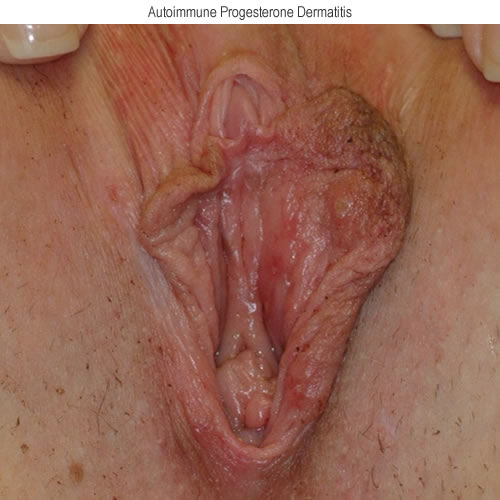

- the color of the epithelium and any lesions, (Annotation H, The vulvar epithelium).

- the texture of the epithelium (e.g. plaques, pustules, nodules, mass), (Annotation H, The vulvar epithelium).

- the integrity of the epithelium (e.g. fissures, erosions, ulcers), (Annotation H, The vulvar epithelium).

From these descriptions (which will include both normal and possibly abnormal findings), the examiner will know the nature of the problem: discomfort without a visible lesion or discomfort with lesions, or some areas of both, and the location of the problem: outer vulva, vestibule, vagina, or any combination of these. Microscopy and adjunctive tests will provide further illumination.

First Pelvic Examination

This examination is an important component of care for many young women, because adolescents and young adults are at an increased risk for sexually transmitted infections, unplanned pregnancy and other gynecologic conditions.1 However, this examination also has the potential to cause anxiety and negatively affect young women’s future engagement in health care.2

Updated professional guidelines have delayed the timing of first cervical cancer screening to 21 to 25 years (depending on whether cytology alone or primary HPV testing is done),3 obviating the need for a routine pelvic examination before the age of 21 years.4 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends the first gynecologic visit take place as indicated by medical history or symptoms.5 From these guidelines, pelvic examinations are not recommended for adolescents younger than 21 years unless there is a clinical indication.6 7

Several factors emerged from a study on preparedness for the first pelvic examination, including age at first examination, informational context, relationship to the medical system, comfort with one’s body, and sexual history.8 While these factors may not be modifiable by clinical practice or professional guidelines, the study emphasizes the the importance of health care providers discussing such topics before conducting the examination and taking these factors into account when conducting the examination. Recommendations exist on how to approach the pelvic examination for women with a history of sexual trauma.9

Preparation and positioning

Give the patient the opportunity to empty her bladder, obtain the patient’s permission for the exam (Annotation D, Patient tolerance for exam), and provide an adequate drape. Explain the flow of the exam and what you will be doing. Offer the presence of an assistant and document the chaperone or the fact that patient declined an attendant’s presence. Start with the patient lying supine on the exam table with the head elevated 30 to 45 degrees.

The term “scoot down to the end of the table,” as if the pelvic examination is an easy childhood game, is offensive to many women, making them feel juvenile and demeaned. Request, instead, that the patient move her hips down to the edge of the exam table, place her feet in stirrups, knees bent and relaxed out to the side. Adjust the angle and length of the stirrups to “fit” the patient. If she is not down far enough on the table, the exam will be more difficult for you and more uncomfortable for her as the speculum handle will press on the gluteal and anal areas and on the table itself. The inability to cooperate with assuming lithotomy position suggests a major obstacle to continuing the examination. (Annotation D, Patient tolerance of exam).

Stirrups with washable padding add to comfort, but standards for changing between patients must be observed.

Necessary materials

Assembling necessary materials in advance helps with the smooth progression of the exam. Materials include saline and tissues to remove excess secretions, blood, or smegma, a measuring tape, or device for quantifying a lesion size, and a large magnifying glass for scrutiny of anatomy or lesions. A hand mirror is important for showing the woman where a lesion is and where a topical treatment is to be applied. Q-tip, culture materials, speculum, and lubricant will be used for other parts of the examination.

Starting the vulvar examination

Uncover the vulva by moving the center of the drape away from you. Try to avoid creating a “screen” with the drape pulled tight between the patient’s knees or in your line of eye contact with her.

To promote comfort and avoid surprise, start by telling the patient you are beginning the examination. Tell the woman that you are going to touch the vulva: “you are going to feel me touch now.” Continue to explain and ascertain the woman’s comfort with the exam as you move to each area examined. Some clinicians feel it is less startling to the woman if she is touched on the inner thighs first, still with the verbal information, “you are going to feel me touch now.”

The twelve vulvar areas to examine

Systematically examine each of the following areas in this order, or in the pattern of your choice. This order was chosen because it moves from outermost to innermost structures in sequence. The key to successful diagnosis is consistent adherence to your routine of looking at all twelve areas for anatomical normalcy, epithelial color, texture, and integrity, and lesions. (Annotation F; The vulvar architecture). Here, some common findings are included.

Groin folds

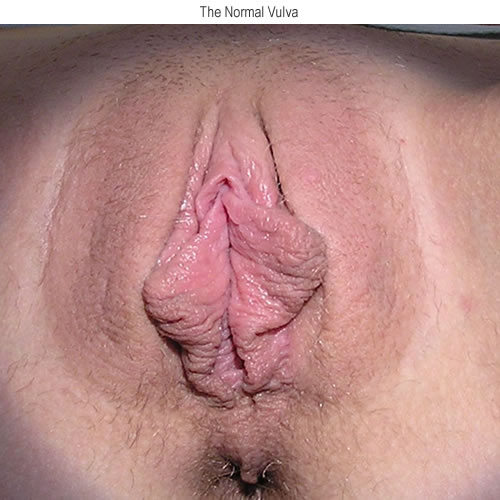

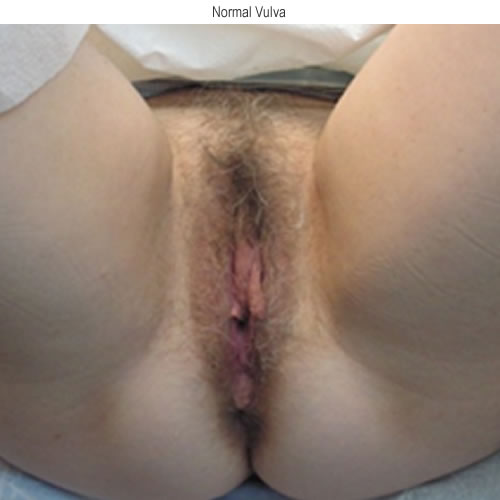

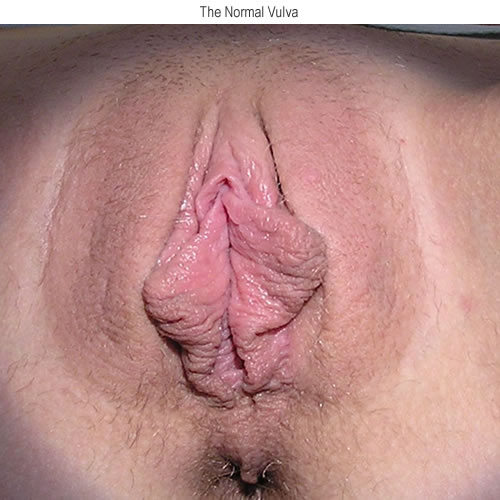

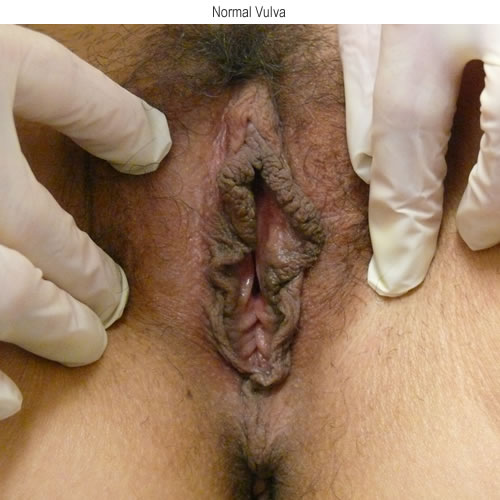

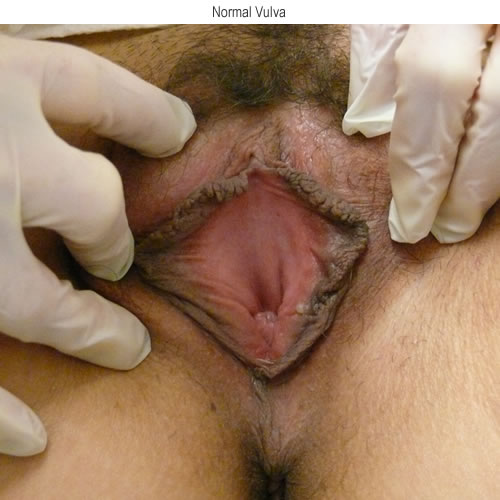

The skin should be normal flesh color, smooth and intact. The following is a normal vulva in a light skinned person.

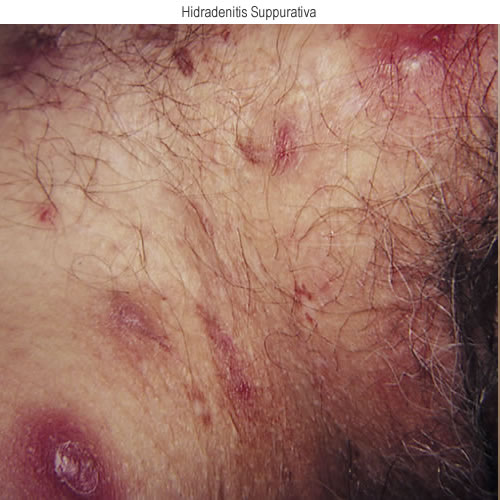

Epithelium in the groin is thin and sensitive, easily affected by use of potent steroids. Look for change in color (from normal to red or gray, or darker brown in dark-skinned people, or other color changes), texture (with papules or edema), or interruption in integrity of the skin (by fissures, scars or pitting from hidradenitis) throughout the vulva. The next four photos show changes in texture and integrity of the skin: lichenification in the first two, then ulcerations from herpes simplex and papules and nodules of hidradenitis in the last two. Palpate for adenopathy.

Mons pubis

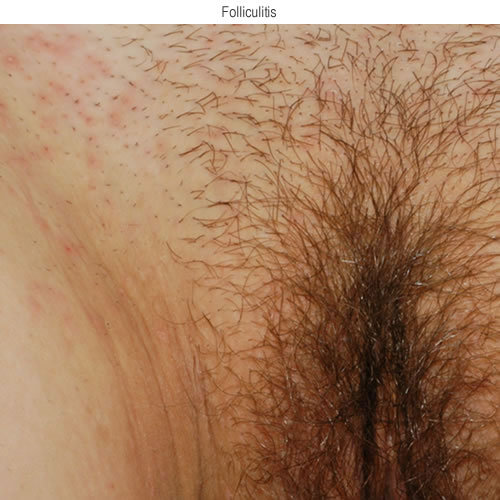

The skin should be normal, flesh-colored, epithelium with pubic hair present or removed.

Look between and around the hairs for abnormalities in color, texture, or skin integrity with possible folliculitis in the first photo, scabby papules from molluscum in the second photo, lichenification in the third photo, and pitting and scars from hidradenitis in the fourth photo.

Labia majora

The skin should be normal, flesh-color, with slightly more pigmentation in pregnant women, or women of dark complexion.

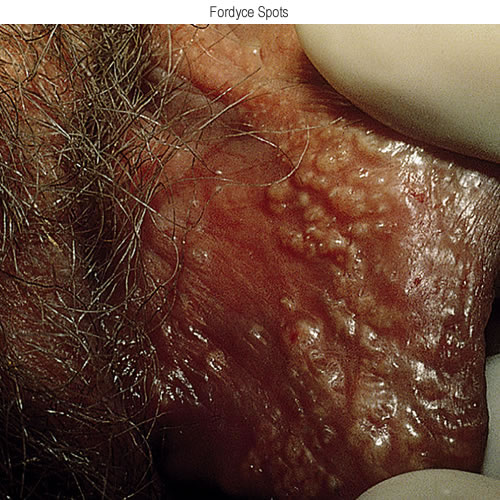

Redheaded or blond women often have deep pink skin on the labia majora. Varying amounts of hair extend to the peri-anal area. Sebaceous glands may appear as yellowish papules, sometimes aggregated in sheets. See these sebaceous glands in the next photo.

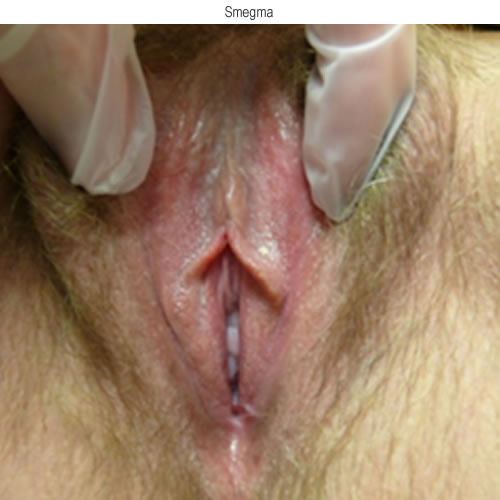

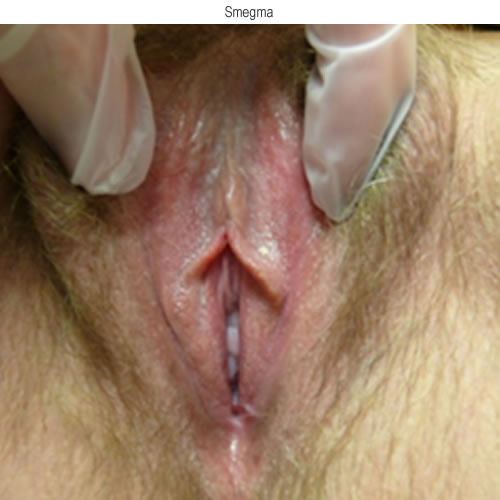

Secretions accumulate as whitish, sticky smegma in skin folds, particularly in the periclitoral area or between the labia minora and labia majora.

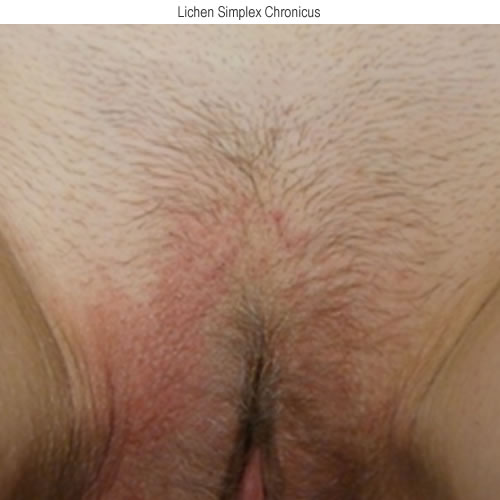

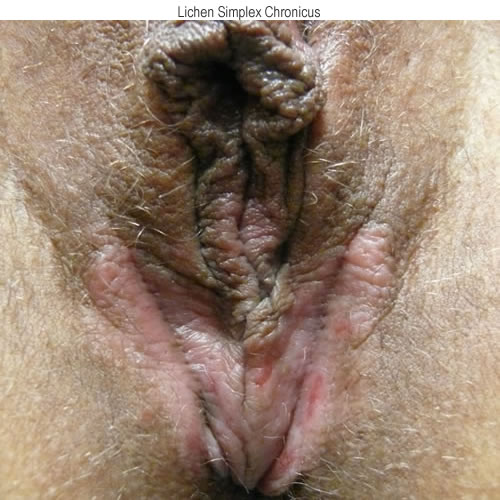

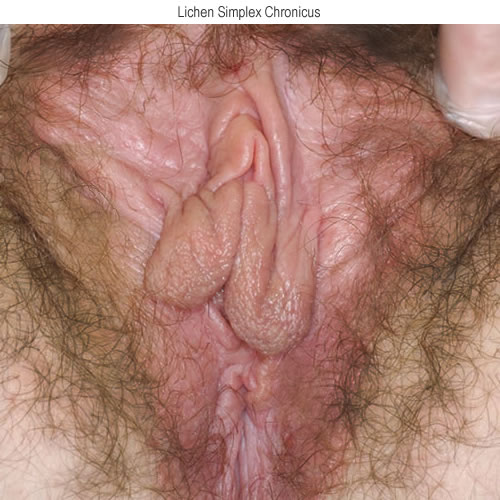

Blockage creates papules or pustules along medial margins. Gently retract the labia majora laterally to view the medial surfaces. Check for broken hairs from scratching, as in the following photo showing lichen simplex chronicus where there are erosions from scratching and thickened skin.

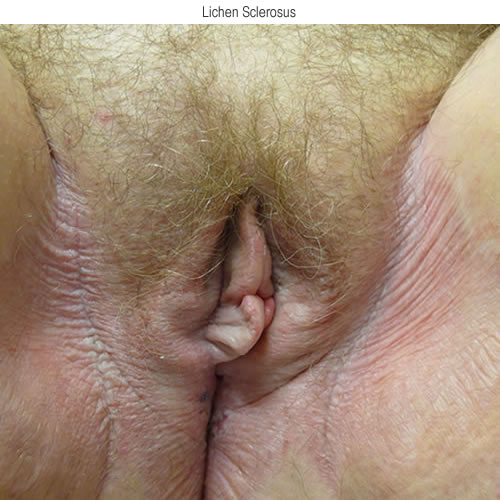

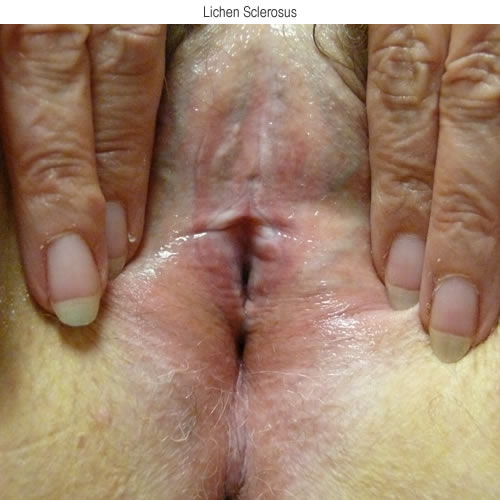

Whitening or erythema in the skin occurs in many conditions, with both being seen quite often. In the following photo of a patient with lichen sclerosus, both are seen extending from the labia majora, out to the groin folds, and up the inner thighs as well as below the introitus.

In the next photo, lichen simplex chronicus is seen with deep erythema, thickened skin with increased skin markings (lichenification), and broken hairs.

Look for defects in integrity of the skin such as fissures or tiny ulcers, alterations in texture such as lichenification, edema, or lesions of scabies, pediculosis, papules or plaques.

Perineum (referring here to the epithelium between the posterior

fourchette and the anus)

The normal skin is keratinized, stratified, squamous epithelium, smooth and flesh colored. Look for color changes of whitening or erythema as in this case of lichen sclerosus.

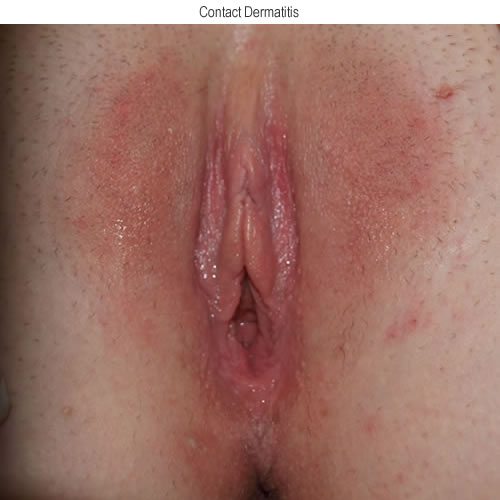

Erythema commonly occurs with contact dermatitis.

Lichenification from rubbing and scratching can present with the characteristic thickening of the skin, whitening, increased skin markings.

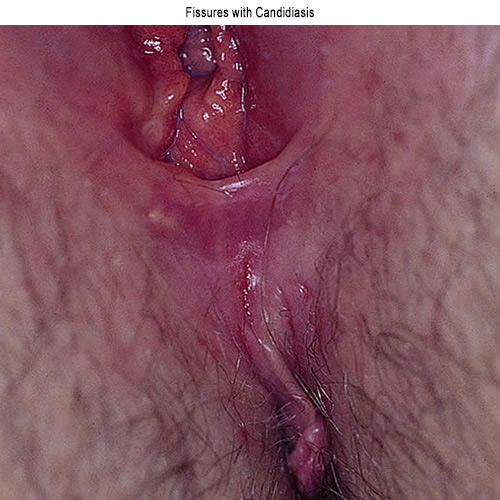

Fissures are commonly seen with yeast infections.

Scars from childbirth are common.

Anus

This represents another area of delicate skin. It is flesh colored, but may show some physiologic hyperpigmentation in women of dark complexion, or pregnant women.

The muscles of the sphincter form slight folds that must be retracted slightly for adequate inspection for color changes (whitening or erythema), alterations in texture such as lichenification, and break in integrity of the epithelium with fissuring. Lichen sclerosus frequently affects this area and is often mistaken for hemorrhoids, which may also be present.

Interlabial sulci

The troughs between the medial margins of the labia majora and the lateral margins of the labia minora are subject to the disorders of partially keratinized skin, subtle hair follicles, sweat glands, and ectopic sebaceous glands. Whitening or erythema are common findings,

fissuring may occur. Smegma is often present.

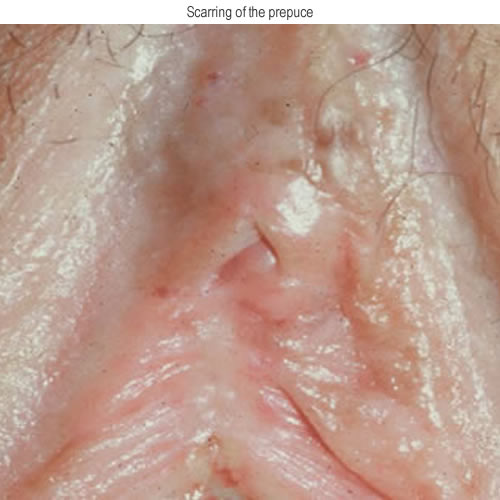

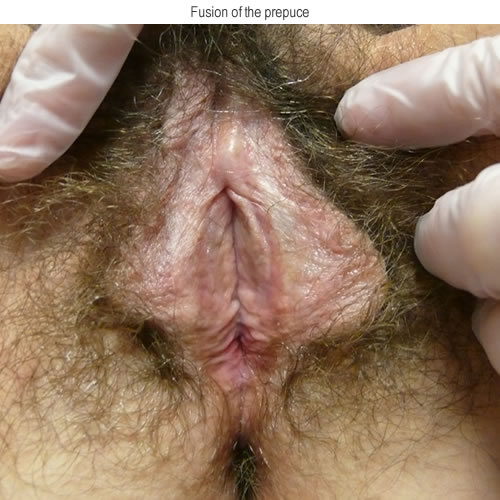

Prepuce of the clitoris

The prepuce is formed by the labia minora joining anteriorly to form the clitoral hood. The hood may be thick and redundant, or thin with the clitoris partially visible. It is normally mobile and easily retracted from the glans. Rarely, the prepuce can entrap smegma or tiny, clipped pubic hairs that become irritants. Adhesions of the prepuce to the clitoris should be carefully evaluated. They may represent scarring from earlier dermatosis. One investigator reported that this is a normal finding in one of four young women.10 However, in a woman with irritative symptoms and color change, active inflammation is likely.

Glans clitoris

The glans is the only visible portion of five component erectile tissue parts, four beneath the skin. The glans itself is not erectile tissue.11 It is covered with stratified squamous epithelium. It is smooth, with no sebaceous, apocrine or sweat glands and varies from pink to slightly violaceous in color. Color change to white or red, fissures, erosions, or blisters may be seen on the glans.

Frenulum

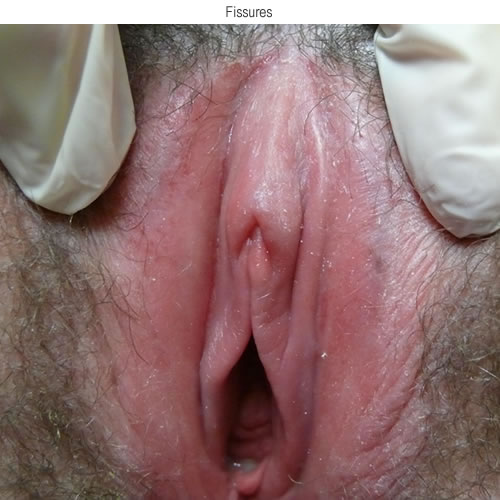

This structure is formed as the labia minora pass posterior to the clitoris to form a supporting sling for the glans. It may exhibit erythematous changes, whitening, or fissuring.

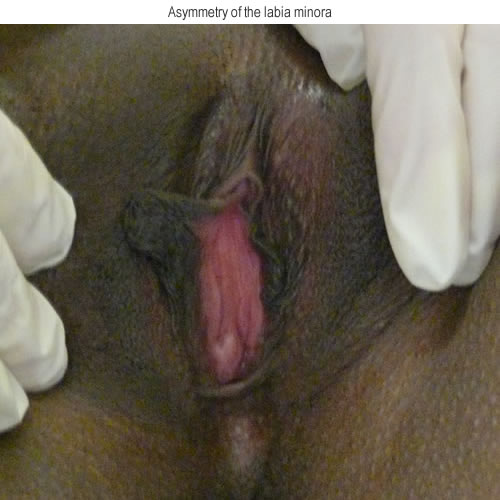

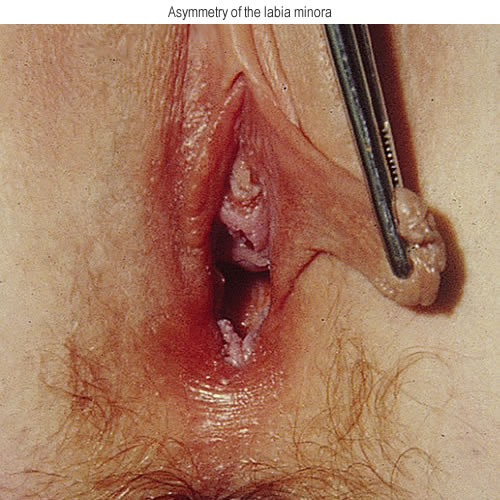

Labia minora

The labia minora are flesh colored folds that vary in size. The skin is cornified, supple and elastic, smooth and intact. They are often pigmented along their lateral margins.

They have sebaceous glands that may appear, similar to those that occur on the labia majora. One or two papillae with filiform, dome-shaped tips (normal variants) may be present.

Often the minora form full folds from frenulum to fourchette, and may protrude past the majora.

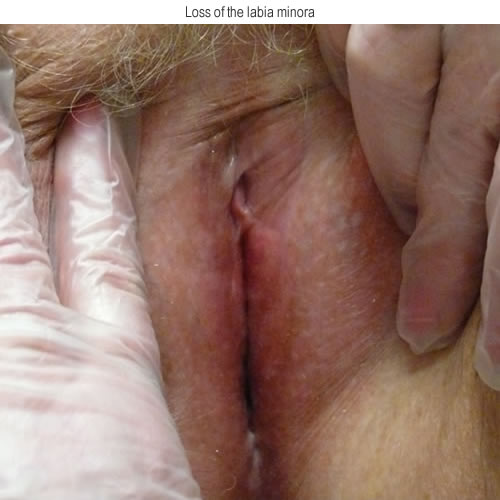

Loss of a portion of one or both labia should be considered as a possible abnormality with search for inflammatory etiologies prior to acceptance as “normal variation.”

With lichen sclerosus or lichen planus, the minora may fuse anteriorly or posteriorly, restricting the introital diameter. The labia minora end medially at Hart’s line where their keratinized squamous epithelium transitions to the non-keratinized, mucosal tissue of the vestibule.

Vestibule

The vestibule is a small area extending from the frenulum anteriorly to the fourchette posteriorly, from Hart’s line at the juncture of the labia minora and the vestibule, to the hymenal ring. The urethra, Skene’s and lesser vestibular gland openings, Bartholin duct orifices and the vaginal orifice are all visible. Soft, filiform vestibular papillae are a normal finding. Sebaceous glands are frequently seen. Look here for erythema or whitening, fissures and erosions, often appearing as bright red, shiny tissue.

Urethral orifice

Located within the vestibule, the urethra may be slit-like or star shaped.

Flesh colored papillary fronds of normal mucosa may be present around the orifice. Bright red projections of prolapsed mucosa (caruncle) are seen with inadequate estrogen.

Look for peri-urethral erythema suggesting inflammation or infection, or whitening with dermatosis.

Ask the woman to point to or touch with a single digit the location of symptoms (itching, burning, stinging, soreness, pain) that brought her in and map these areas mentally. It is helpful, later, to indicate these areas on a diagram of the vulva so you don’t forget. (Annotation I, Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test).

Checking for tenderness in the symptomatic areas

Next, note any tenderness to palpation of symptomatic areas. The Q-tip test will be positive with vulvar pain of known etiology such as Candida or herpes, or with vulvodynia. As you will learn, however, (Annotation I, Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test), the Q-tip test, even with the presence of neurogenic pain, may be negative, with no tenderness to gentle touch.

Make mental or written notes, draw a sketch, mark a diagram, or ask an assistant to document these sites. Often many areas are not symptomatic, making the job easier. However, remembering the architectural details of all twelve anatomical sites along with the pathology is challenging. We have found photographs (taken with signed consent) that become part of the woman’s chart to be very helpful.

Inspecting for architectural changes

Look for changes in architecture. The prepuce in a normal woman can always be gently retracted to reveal the full glans; adherence of prepuce to glans clitoris or fusion over the glans is abnormal. Apparent absence of the prepuce showing the whole glans, may be abnormal. Missing portions of the labia minora, fusion of the minora anteriorly or posteriorly to restrict the diameter of the introitus also represent pathology. (Annotation F, The vulvar architecture).

Inspecting for color, texture and alteration in integrity

Gently retract the tissue, evert folds, lift, and separate tissue interfaces in each area. Check for lesions and color changes in between pubic hairs on mons and majora. Note color of the epithelium in a normal area of the vulva and compare any questioned area with the normal. Make a note of skin-colored lesions, whitening, erythema, dark brown hyperpigmentation, black or blue lesions. Then check for changes in skin texture – plaques, papules, pustules, cysts, nodules. Finally, scan the skin for alterations in integrity: fissures, erosions, ulcerations. (Annotation H: The vulvar skin). Palpate for masses not visible to the naked eye in the labia, perineal or peri-clitoral area; map, describe and measure, also noting location of itching or pain.

Use a hand mirror to show normal anatomy or to demonstrate an abnormal finding. Congratulate the woman on completion of the vulvar examination and move on to evaluation of the vestibule (Annotation I: Pain and symptom mapping and the Q-tip test), the pelvic floor (Annotation L: The pelvic floor), the vagina (Annotation M: Perform speculum exam and Annotation P: Vaginal secretions, pH, microscopy, and cultures), the hymenal ring and pelvic organs. (Annotation Q).

Regardless of primary complaint or suspected pathology, all these pieces are necessary to obtain a full picture. If for example, pelvic floor pathology is present, it is likely to play a significant role in the maintenance and exacerbation of pain.12

- It is important to determine where and how severe pain is early in the sequence; otherwise, the examination may exacerbate the problems.

- For the same reason, it is equally important to do a single digit examination of the pelvic floor prior to speculum or bimanual.

- Always make sure the prepuce can be retracted; scarring here is an important finding.

- Loss of all or part of the labia minora is also a significant finding.

- Fissures are often tiny and easily missed. Gently retract surfaces and look closely.

- Broken hairs are a clue to intense itching and scratching.

References

- Guttmacher Institute. Fact sheet: adolescent sexual and reproductive health in the United states. Available at: guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/american-teens-sexual-and reproductive-health. Retrieved August 8, 2018

- Yanikkerem E, Ozademir M, Tatar A, Karadeniz G. Women’s attitudes and expectations regarding gynaecological examination. Midwifery 2009;25:500-8

- Marcus, Jenna Z. MD; Cason, Patty RN, MS, FNP-BC; Downs, Levi S. Jr. MD, MS; Einstein, Mark H. MD, MS; Flowers, Lisa MD. The ASCCP Cervical Cancer Screening Task Force Endorsement and Opinion on the American Cancer Society Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 25(3):p 187-191, July 2021. | DOI: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000614

- Martinez GM, Qin J, Saraiya M, Sawaya GF. Receipt of pelvic examinations among women aged 15–44 in the United States, 1988–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 339. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019

- ACOG Committee opinion no. 754: The utility of and indications for routine pelvic examination. Obstet Gynecol 132(4):e174–80. 2018

- Well-woman visit. Committee Opinion No. 534. American college of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:421-4

- Marcus, Jenna Z. MD; Cason, Patty RN, MS, FNP-BC; Downs, Levi S. Jr. MD, MS; Einstein, Mark H. MD, MS; Flowers, Lisa MD. The ASCCP Cervical Cancer Screening Task Force Endorsement and Opinion on the American Cancer Society Updated Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 25(3):p 187-191, July 2021. | DOI: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000614

- Bryan A, Chor J. Factors influencing young women’s preparedness for their first pelvic examination. Obstetricians Gynecol 2018;132:479-86

- Adult manifestations of childhood sexual abuse. Committee Opinion No 498. american college of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetricians Gynecol 2011;118:392-5

- Weismeier E, Masongsong EV, Wiley DJ. The prevalence of examiner-diagnosed clitoral hood adhesions in a population of college-aged women. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008; 12:307-310.

- Neill SM, Lewis FM. Basics of vulval embryology, anatomy and physiology. In: Neill, SM, Lewis FM, eds. Ridley’s the Vulva, 2nd ed., Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009: 15.

- Reissing ED, Brown C, Lord MJ, Binik Y, Khalife S. Pelvic floor muscle functioning in women with vulvar vestibulitis. J of Psychosom Obstet and Gynecol. June, 2005. 26(2): 107-113.